AOTH’s interest rate predictions have been bang on – Richard Mills

2023.11.16

At Ahead of the Herd, we pride ourselves on being right, when it comes to macroeconomic trends that underpin our key investment theses.

I have always maintained, that “As a general rule, the most successful man in life is the man who has the best information.” (Benjamin Disraeli) Being correct about a trend, and timing it right, is what gives AOTH investors the edge, setting them apart from the average punter.

In analyzing US economic data, it used to be that several factors had to be taken into account when making predictions about the US economy. This included interest rates, inflation, the money supply, economic growth, retail spending, housing prices, etc.

While all of these continue to make financial news, these days the two most important are interest rates and inflation — both of which are watched and controlled by the US Federal Reserve. You can’t be an economic forecaster in 2023 without vigorously monitoring the Fed, hanging on Chairman Jerome Powell’s every word so as to determine whether, and when, the Fed will raise interest rates to cool inflation and slow the economy, pause its rate-hiking cycle, or start lowering interest rates without adding to inflationary pressures.

Stocks, bond yields, the dollar, and precious metals all rise and fall based on Fed decisions, or even the hint of a forthcoming decision.

The reason the Fed is so important comes down to two words: quantitative easing.

QE for short, is a technique used by the US Federal Reserve and other central banks to stimulate the economy in times of crisis. The Fed buys up securities from its member banks, thereby adding new money to the economy (this is where the expression, the Fed is “printing money” comes from). It’s a way of funding new expenditures, without actually dipping into the federal budget.

The idea is to free up more money for banks to make loans to individuals and businesses, thus growing the economy. The money is not cash, but credit that is added to banks’ deposits. When it wants to print money, the Fed lowers the benchmark federal funds rate, and banks in turn lower their interest rates, making capital more affordable so that businesses and investors are more likely to borrow.

The Fed used quantitative easing in the wake of the 2008-09 financial crisis and it did so again in 2020 to deal with the coronavirus pandemic.

QE was successful in preventing a financial meltdown during 2008 and 2020, but the effect has been a reliance on cheap credit that fueled both a stock market bubble and a real estate bubble. Bond investors also became addicted to Fed stimulus.

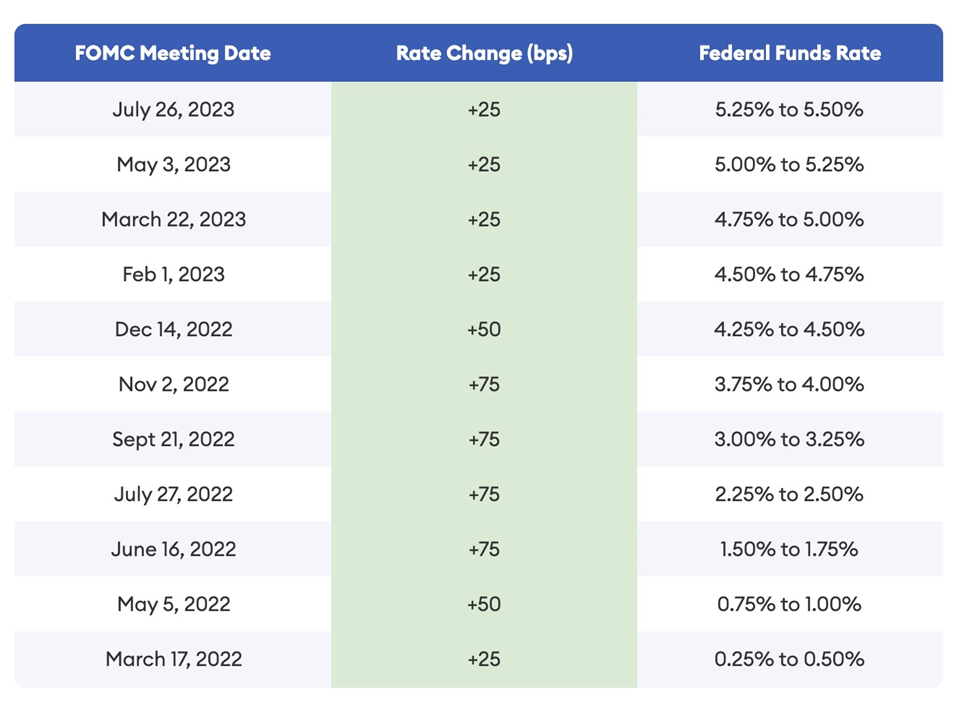

The Fed’s policy changed dramatically following the covid-19 pandemic, due to inflation. After restrictions were eased, pent-up demand meant consumer spending soared, helped in part by the stimulus payments doled out by the federal government. The effect was highly inflationary, and led to a series of interest rate hikes. In 17 months, to July of 2023, the Fed hiked its benchmark rate 11 times, bringing it to a range of 5.25 to 5.5%, the highest in 22 years, before pausing — the Fed did not increase the rate at its September and October meetings. It’s easy to forget that in early 2022, interest rates were near 0.25%, as the table below shows. They’re now at 5.5%, a 22X increase.

The Fed played its part in adding to inflation by increasing the money supply. By conducting open market operations, i.e., buying government bonds and mortgage-backed securities from banks, the Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet by $7 trillion between 2007 and 2023. In March, 2022, when the pandemic began, the Fed had $4.3 trillion on its balance sheet. By Nov. 1, 2023, it was at $7.8 trillion.

If the money supply grows too big relative to the size of an economy, the unit value of the currency diminishes; in other words, its purchasing power falls and prices rise.

US inflation hit a pandemic-era peak of 9.1% in June, 2022, the highest rate since November, 1981, a long way from the Fed’s targeted 2%.

The Fed’s response to inflation (and employment data) has guided its policies since inflation became a problem in the months following the pandemic. And it’s our predictions, based on publicly available data, that have been mostly right, and form the basis of this article.

Too little too late

Cast your minds back to the fall of 2021, when we were criticizing the Fed for not doing enough to tackle inflation, then the new bogeyman of the US (and global) economy.

How the Fed mishandled 40-year-high inflation

Several months after the US Federal Reserve began describing the country’s inflation problem as “transitory”, the central bank in December, ’21, finally admitted that rapidly rising prices of goods and services are a serious threat to the American economy and its recovery from the coronavirus pandemic.

The problem was the Fed’s response, three modest interest rate hikes by the end of 2022, lifting rates to between three-quarters of a percent to 1%, was woefully inadequate for this level of inflation.

Arguably the Fed was “behind the curve” from the beginning. It should have foreseen that half a trillion dollars in direct stimulus payments, combined with high demand from a recovering economy set against virus-related supply chain interruptions, would be highly inflationary.

Instead, the organization at first denied that inflation was even on the horizon, then said any inflation would be just temporary, transitory, and would end once supply-chain wrinkles were ironed out. Only after the publication of some truly shocking price statistics following Thanksgiving did Fed Chairman Jerome Powell admit that inflation is not actually transitory and that something more serious is going on.

Instead of showing that the Fed is serious about controlling inflation, i.e., hawkishly raising rates sooner and higher, Powell and his board of governors remained dovish, bringing a pea-shooter to an inflation fight requiring a bazooka, a bucket brigade to a raging inferno, pick your metaphor it all pointed to the same conclusion: the Fed was doing too little too late.

We can see the desperation in how everything is happening that much faster than the last time the Fed tried to quell rising inflation in 2015.

Whereas the Fed slowly began tapering its asset purchases in early 2014 and took five years to run off its balance sheet, the FOMC announced it would double the speed of the taper to $30 billion a month and end quantitative easing entirely by mid-March.

The warp-speed taper was due to the strength of the US recovery, what Powell described as “growth above potential”, the unemployment rate falling and “inflation well above target.”

Once QE ended, the Fed planned to begin raising short-term rates three times in 2022, bringing the target range to between 0.75% and 1% by the end of 2022.

Yet that wouldn’t be enough.

Economist and gold bug Peter Schiff argued that the Fed should bring rates as high as 7% to tame inflation.

I went on record as saying that a more reasonable solution, without killing the economy, would be to boost the three raises in 2022 say to 1% each, or 1.25%, bringing them within a range of 3% to 4% by year-end. As the chart below shows, this is exactly what happened.

I argued, how can a 1% increase at the high end of the range possibly do anything to stop the 9% increase in goods prices and the 7% inflation in services?

The market needed to hear the Fed was serious about battling inflation. Under their leadership, or lack of, inflation almost hit double digits.

Without adequate tightening, and with all the other factors surrounding rising prices including continued supply chain problems, the food and energy crisis and climate change, still happening, they are almost certainly moving higher, I argued, despite what the Fed says and does.

If the actual inflation rate is close to 10%, year over year, how much of your purchasing power has been destroyed?

At AOTH we firmly believe that to protect our investments we need a hedge against inflation and we have always chosen junior gold and silver mining stocks, as historically showing the greatest leverage to rising metal prices.

The Fed’s half-full glass

2% inflation target blinding the Fed to economic reality

The US Federal Reserve started off declaring that historically high levels of inflation were “transitory”, and would go away with the resolution of covid-related supply chain bottlenecks. When inflation rocketed from 5.4% in September, 2021 to 8.5% in March, 2022, then 9.1% in June, all the Fed’s talk of transitory inflation dissipated, and its strategy switched to fighting inflation through a series of aggressive interest rate hikes.

At first it didn’t work. Inflation actually accelerated after the Fed began raising rates in March, ’22, prompting officials to hike them by a half-percentage point that month, instead of the earlier 25 basis-point expectation, and 75 basis points in June rather than the 50 points the Fed thought would be sufficient. In July, at the Federal Open Market Committee’s regular meeting, the central bank approved another 0.75% increase, lifting its benchmark overnight borrowing rate to a target range of 2.25% to 2.5%.

It seemed the Fed was hell-bent on bringing inflation down to its 2% target, despite indications its tightening has already damaged the US economy, and was pushing it rapidly into recession.

It didn’t shock any of my readers to learn that Federal Reserve officials, including Chairman Jerome Powell, was playing down any recession talk, preferring to focus on the bright points of the US economy that allowed them to keep raising interest rates. In fact, they didn’t even care if economic growth slowed to the point of recession; actually that would be a good thing, since it would likely move the inflation rate down, closer to the coveted 2%!

It all pointed to a battle that governments and the Fed appeared to be waging against the very people they were trying to help: consumers.

The US central bank was raising interest rates to fight inflation, while governments around the world worked at cross-purposes by investing trillions in infrastructure programs — both “green” and traditional “blacktop”, thus fueling commodity inflation that worked its way up supply chains to the consumer, who ended up paying more for, well, everything.

The Fed didn’t seem to care if they took down the economy with their interest rate hikes, their only concern — really they only have two mandates, both quite narrow, controlling inflation and preventing unemployment — was to get 2% inflation. All the negative impacts associated with higher interest rates, including low or negative economic growth, were secondary.

Targeting the wrong inflation

Why the Fed is wrong about inflation coming down

US inflation peaked in June, 2022 at 9.1%, then began dropping. Was this not proof that interest rate hikes were working?

At AOTH, we argued that the Fed was seriously under-estimating how much prices were rising, especially for the all-important US consumer, whose spending comprising a whopping 70% of the country’s GDP.

The Fed’s go-to inflation gauge, core PCE, under-weights rent and over-weights health care. It also strips out two of the most vital categories of household spending, food and energy/ gasoline.

The fact that the central bank’s preferred measure of inflation creates a discernible gap between the rate of price increases for necessities, and the one for discretionary purchases, puts the Federal Reserve’s tightening path at risk of veering off course, maintained Danielle DiMartino Booth, a former adviser to the president of the Dallas Fed.

Surely for the broader CPI to fall substantially, food and energy costs must decline, but when I looked at the energy crisis in Europe, UK food prices exceeding 10%, and OPEC’s 2 million barrels a day production cut keeping oil prices strong, I had my doubts whether this would happen anytime soon.

Supply-side inflation

Will the Fed raising interest rates cause a recession?

Around Easter, 2022, Goldman Sachs published a report putting the odds of a recession at about 35% over the next two years. The influential investment bank noted that 11 out of 14 tightening cycles in the US since World War II have been followed by a recession within two years.

Bloomberg wrote, The consensus is that the Fed is so far behind that curve when it comes to increasing rates that it will have no choice but to tighten monetary policy so severely that it forces the economy to contract to get inflation under control.

At AOTH we were, at first, among those in the recession camp, but we also raised the question, how aggressive will the Fed be in raising interest rates to fight inflation?

The Fed thought raising interest rates would quell demand for goods and services (aggregate/ total demand) which was exceeding aggregate supply, causing inflation. Lessen the demand, lower the inflation. Simple, right?

Wrong. I had no problem agreeing that demand was partially responsible for decades-high inflation in the US, Canada and Europe. But attributing higher prices to the fact that the economic rebound has outpaced the ability of manufacturers to brings goods like semi-conductors to market (the “supply chain issues” theory that has been repeated ad nauseum — was not, imo, the main reason.

Also, our current bout of inflation is unlike the last time prices rose beyond the Fed’s 2% target (from about -1.5% in August 2009 to 3.75% in August 2011), which was all about quantitative easing.

The real culprit, I maintained, was not supply chains but actual supply, especially of raw-material commodities that had skyrocketed. A deeper understanding reveals that the supply shortages we were experiencing were not temporary, but structural in nature.

Inflation is chipping away at the standard of living in a number of developed countries. Here in North America, it’s the worst we’ve seen since the 1980s, although prices have moderated somewhat since 2022. Everything is going up, and people are hurting, especially the poor and working poor. For those with mortgages, loans and credit card debt, higher interest rates have only added to the misery.

Yet one of the Federal Reserve’s most important tools for fighting inflation is to raise rates. We asked the question, how aggressive will the Fed be in raising interest rates to deal with inflation?

Previously I believed that the Fed would “go hostile” in raising rates so high, it would crash the markets and cause a recession. Having seen the consumer savings figures, I was no longer so sure. Direct stimulus payments and other generous social programs lifted checkable deposits for households from $1.16 trillion at the end of 2019 to $4.06T in December, 2022. That is a massive cash cushion consumers were sitting on — nearly quadruple the previous high of $1.41T.

A Washington Post article reported that Americans currently had an extra $2.6 trillion in savings.

Raising interest rates was not going to stop consumers from spending, if that was the Fed’s goal.

The Fed thought they could create demand destruction through higher rates, and they have succeeded, to some extent. However, as we have argued, this inflation is not about quantitative easing; reducing the Fed’s $8 trillion balance sheet won’t curb inflation.

Remember, the Fed is constrained in how much further it can lift rates, due to the crushing amount of debt — including government, corporate and household.

So we changed our view. We now believed the Fed would raise, but not to the point where it hurts the economy and causes a recession. A middling amount, say 2-3%, would likely be enough for the Fed to say it is “doing something” about inflation, even though no amount of interest rate hikes could do anything to fix the structural shortages in commodities. And how could they?

How does raising rates to curb demand avert the energy crisis or grow more food?

The debt problem

America’s debt problem is only getting bigger

The US officially has a debt problem. America’s gross national debt sits at $33.7 trillion, or 124% of its GDP! The bigger problem, though, is the pace at which it’s doing so, leading to ballooning interest payments.

According to the CBO’s (Congressional Budget Office) projections, interest payments will total around $71 trillion over the next 30 years and take up 35% of all federal revenues by 2053.

Over the past decade, US national debt has nearly doubled, including a three-year period 2020-2023 during which federal spending amounted to a jaw-dropping $28 trillion.

One implication of America’s fast-rising national debt is how it impacts its financial condition in the eyes of investors. Earlier this year we got an answer from Fitch, which downgraded its US credit rating from the top level of AAA to a lower level at AA+.

The ratings agency, one of the three biggest in the world, cited its decision to the “steady deterioration” in US governance over the last 20 years.

Understandably, right after the credit downgrade, 10-year Treasury yields jumped 11 basis points to nearly 4.2%, as investors sought higher compensation for the risk of holding long-term US government debt. Two-year yields also spiked.

Beyond the simple fact of inflation getting closer to the Fed’s 2% target, which would mean “mission accomplished” for the central bank, there is another reason why the organization cannot continue to hike rates to quell inflation for much longer. Hint: it has to do with the debt.

Even when the Fed starts cutting rates, due to the delay of rolling over maturing debt, interest payments will keep going up for the foreseeable future. As Zero Hedge recently observed, if rates keep rising “higher for longer”, the current weighted average for total outstanding debt will go from 2.76% to 4% in one year:

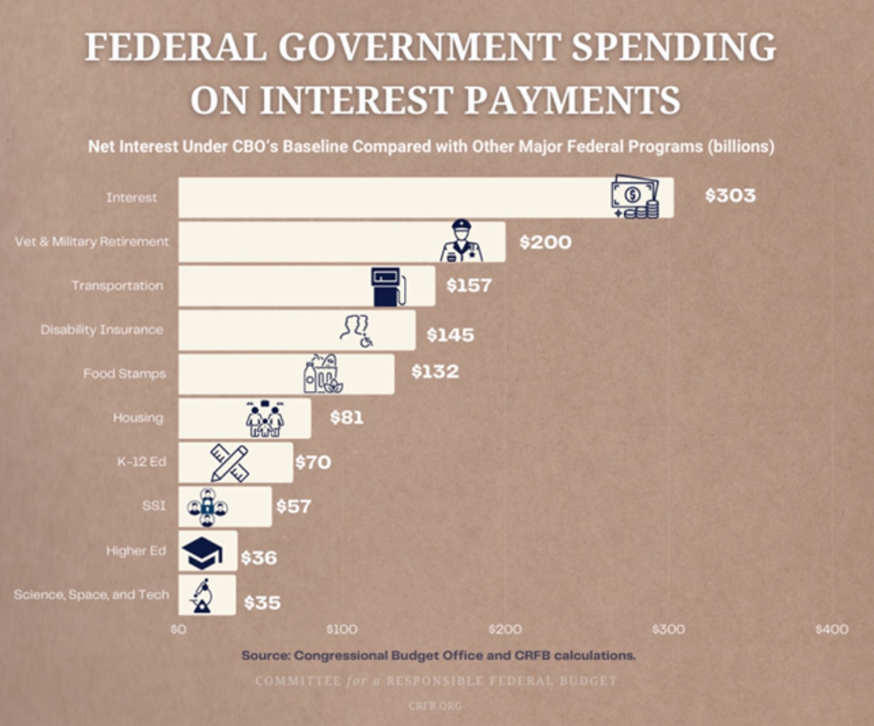

That would be a complete disaster for the US, and it would mean that interest payments on total US debt of $32.3 trillion would hit $1.3 trillion within 12 months, potentially making interest on the debt the single biggest US government expenditure and surpassing social security!

The ballooning interest on the national debt mean that budget cuts are inevitable; they are needed just to keep the government solvent. Where will the reductions occur? The answer is Social Security and Medicare/ Medicaid. Both programs are unsustainable the way they are currently structured.

Over the next decade, Medicare and Social Security spending are both expected to double. Yet the government has no money in the bank for future expenses and there is no serious proposal to change that.

How high will they have to raise the debt ceiling to afford these expensive, unfunded liabilities? How much interest will have to be paid on this higher debt?

With 17 cents out of every dollar now going to paying the interest on the debt, it won’t be long before debt servicing costs are the biggest line item, surpassing even the true, bloated defence/ war-making budget. And who is to blame? Both the GOP and Dems.

Soft landing

For over a year now, the financial talking heads have been discussing the likelihood of a “hard landing” versus a “soft landing” for the US economy — based on the actions of the Federal Reserve, which controls the money supply and interest rates.

These are the tools the central bank uses to keep the economy running near full employment, and inflation in the neighborhood of 2%, a kind of “Goldilocks zone” wherein the economy is neither growing too fast, fueling higher consumer prices, nor too slow, which can stall economic growth and result in layoffs.

Since March, 2022, the Fed has been working to control inflation that at one point was the highest in 40 years. They’ve been doing this by raising interest rates in increments from essentially zero to +5%. In June the Fed paused its rate-hiking but on July 26, they raised the federal funds rate another quarter percentage point, to 5.5%. No more rate increases occurred over the next three monthly meetings.

I’ve been right in my prediction that the Fed would pause in June, and hike once or twice more before the end of the year.

However, despite rising rates, there will arguably be no hard landing, or recession. The reason is due to higher-than-expected corporate profits, and the realization by the Fed, that they can no longer keep raising interest rates.

Corporate profit-taking is greasing the runway for a soft landing

Companies’ cost inputs have all gone up due to inflation so they are forced to raise prices to maintain their margins.

Less justifiable is so-called “shrink-flation”, the sneaky practice of putting less product into packages, and charging the same price for it as before the shrinkage. Shrinkflation is normally attributed to food but it could really be any product.

The bottom line is companies are making huge profits right now due to greed-flation and shrink-flation, and there is a third factor pushing profitability even higher. Let’s call it the “reverse yield curve” and here’s how it works:

During the pandemic of 2020-22, the Fed slashed interest rates to near 0% and many companies benefited from the low rates by taking on huge amounts of debt. And why not? It was practically free money.

Normally when corporations borrow, it eats into profitability due to the interest they have to pay on their loans. This time is different. By locking in at rock-bottom interest rates, companies paid, and continue to pay, minimal interest, while at the same time, they are plowing their profits into high-interest-bearing investments that, thanks to a 16-month rate hiking cycle, now pay around 5%.

By shining a light on corporate profitability, it’s easier to see why the stock market has been soaring lately — the technology-heavy Nasdaq Composite Index gaining almost 32% in the first half of the year. U.S. Bank points out that, to July 5, the S&P 500 regained more than half of the bear market losses suffered in 2022. The chart below also shows that the level of decline in the most recent bear market cycle is not as dramatic as the previous three.

More importantly, with companies making money hand over fist, they are fueling the job market. Unemployment, a key Fed metric, is currently at 3.9%, nationally, and at or near record lows in half of US states. Companies are paying higher wages to attract the best people, and these employees are spending the extra money out in the economy, or stuffing it into high-interest-bearing savings accounts just like corporations are doing.

In this way things aren’t really going according to the Federal Reserve’s plan. The Fed wants to “kill the job market” but I don’t see how that happens with corporations making so much profit. In fact companies now have cash to hire more people, defeating the Fed’s goal.

The upshot, in my opinion, is we get a soft landing with no recession, with the important proviso that the Fed pauses its rate-hiking cycle, which it has already done. For the Fed this means inflation stabilized or reduced, and from the look of things, there isn’t far to go. Remarkably, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates just enough to stop the economy from experiencing high inflation, without causing a severe downturn. And it’s done it at an extremely fast pace.

The latest data shows US inflation at 3.2%, a dramatic reduction since July, 2022, when prices were rising at 8% compared to a year earlier.

How did inflation drop so much? Should the Fed be given credit? A recent article in Project Syndicate states that disinflation (the reduction in inflation) is due to transitory price increases, brought about by supply disruptions and sectoral shifts in demand. In certain sectors, such as automobiles and housing, prices simply self-corrected. In the auto sector’s case, this was when chips again became available. For housing, as leases expire, more inventory becomes available, lowering prices.

The article is adamant about the Fed not having much of a role in disinflation:

Given that its interest-rate hikes did not help resolve the chip shortages, it cannot take any credit for the disinflation in car prices. Worse, the rate hikes probably slowed the disinflation in housing prices. Not only do significantly higher rates inhibit construction; they also make mortgages more expensive, thus forcing more people to rent instead of buy. And if there are more people in the market for rentals, rental prices – a core component in the consumer price index – will increase.

I’m quite sure the Fed has the same information that we do, about corporate profits, but here’s the thing: what has been helping corporations is hurting the Fed, because the central bank must now pay out more interest on short-term debt such as US Treasuries.

Arguably, the Fed may have to settle for slightly higher inflation than their normal 2% because they can’t keep raising interest rates for the simple reason that they can’t afford it. The chart below should clarify things. It shows the annualized interest payments on federal government expenditures.

The annual payment on US federal debt, which currently sits at $33.7 trillion, is about to hit $1 trillion, surpassing how much the US pays every year on defense!

Interest on the debt on track to exceed military expenditures

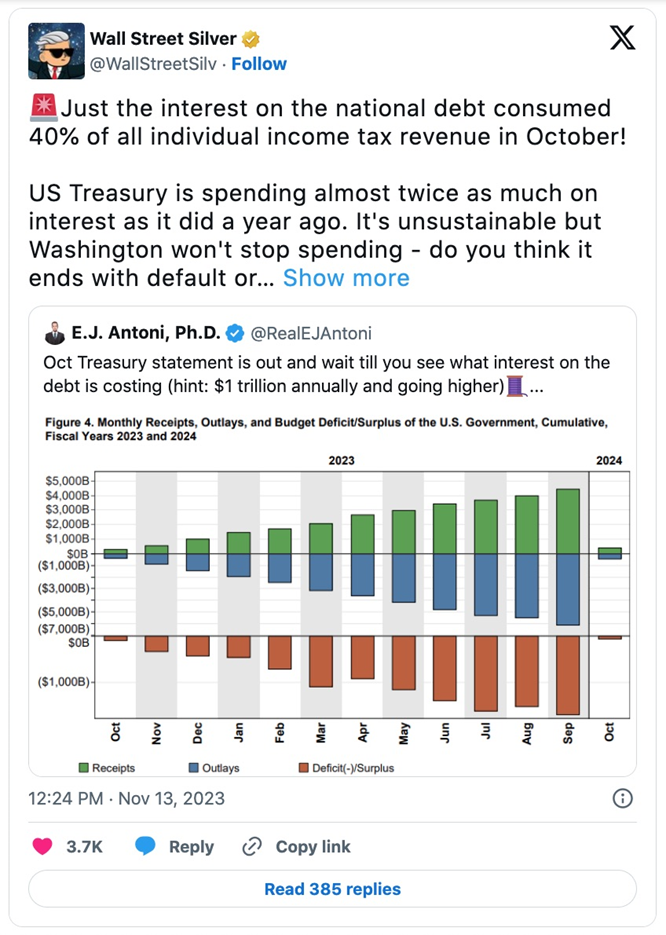

According to Citizen Watch Report, interest payments on the national debt used up 40% of all the money collected from individual income taxes in October. The US Treasury is now spending almost twice as much on interest as compared to the previous year.

The Fed is insolvent

Moreover, the Fed is essentially broke. If it was a regional bank it would already have been taken over due to its obscene balance sheet, whose assets now total over $8 trillion. The Fed has no reserves to draw from, no more bullets in the chamber, so its only choice is to print money. Increasing the money supply is inherently inflationary.

Source: Statista

Economist Nouriel Roubini believes, and I agree, that the increase in long-term interest rates is leading to massive losses for creditors/banks holding long-duration assets such as 10, 20, 30-year Treasuries. The economy is thus falling into a “debt trap”, and central banks confronting this dilemma will end their monetary tightening/ inflation fight so as to avoid a financial and economic meltdown.

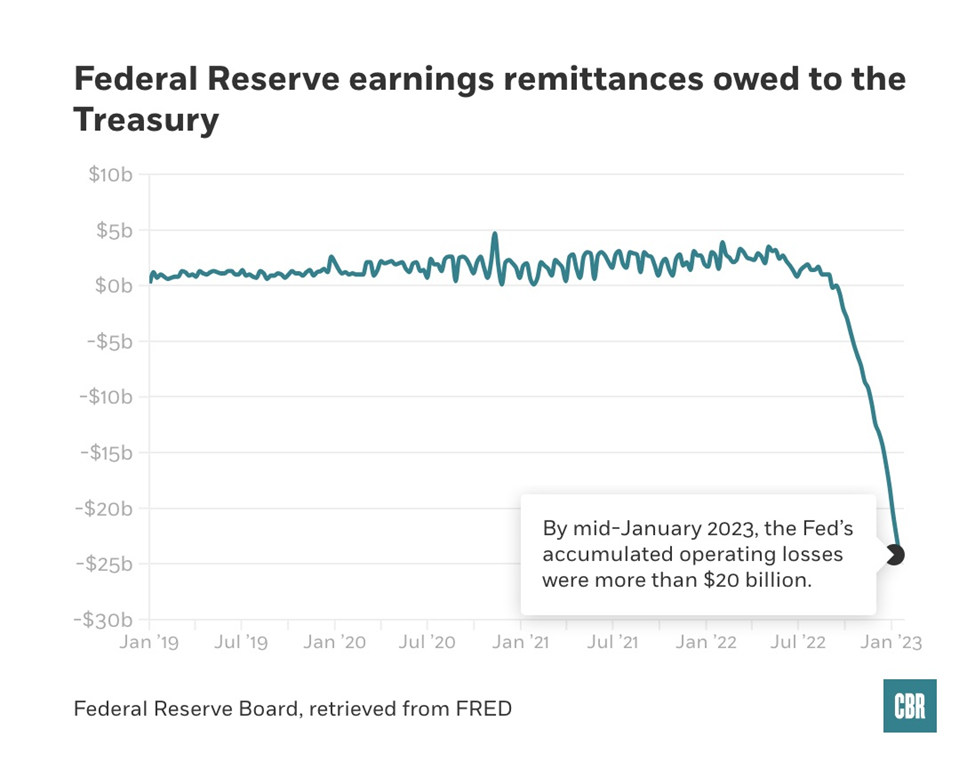

As I’ve said, the Fed knew full well what would happen to banks and themselves if they started raising interest rates.

The Fed knew that by hiking interest rates, it would crater the value of its own vast investment portfolio.

For the first time ever, in September 2022, it was reported the Fed lost money, almost 3/4 of a trillion dollars on mark to market. That’s a result of the plummeting prices of the Fed’s government bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

The Fed’s loss at the end of the second quarter, 2023 was 17 times its total capital, making it deeply insolvent on a mark to market basis. If the Fed was a regional bank it would have been closed and taken over.

Of course, the Fed will never go bust. If it needs to intervene in the bond market, like the Bank of England did, it can just print money to buy government bonds being dumped by failing banks.

The present

The accuracy of our predictions becomes crystal clear when we take a look at some of the current headlines. In early November the Federal Reserve said it would keep interest rates between 5.25 and 5.5%, putting a check mark in my box saying that the Fed would pause its interest-rate hikes by the end of this year and begin lowering them, the so-called pivot, likely in the first half of 2024.

Indeed US inflation is coming down, giving the Fed more reason to continue the pause and start cutting. On Nov. 14 it was reported that inflation slowed in October, with the core consumer price index increasing just 0.2% from September. Core CPI excludes food and energy costs. Shelter prices, which make up around a third of the overall CPI, climbed 0.3%, half the prior month’s pace.

More detail on the inflation figures comes via Statista:

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) increased 3.2 percent over the last 12 months, down from 3.7 percent the previous two months and below consensus estimates of 3.3 percent. On a monthly basis, prices were unchanged for the first time since July 2022, as a drop in gas prices offset a further increase in rents and other costs of shelter. Meanwhile core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, continued its downward trend, falling to 4.0 percent in October – the lowest rate since September 2021.

However, Statista observed the dramatic increase in consumer prices over the past three years, since covid stimulus spending combined with covid-related supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine to create an inflationary perfect storm:

As of October 2023, the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) was up 18.7 percent compared to February 2020, the last month before the Covid-19 pandemic. Assuming the Fed’s targeted 2-percent inflation rate, prices would only have increased by 7.5 percent during that period, illustrating how severe the recent inflation surge has been.

Still, according to Bloomberg,

[I]nflation has settled substantially from a 40-year high reached last year. That’s led several Fed policymakers to signal that they may be done raising interest rates, but Chair Jerome Powell has repeatedly stressed the central bank could hike again if needed.

The S&P 500 index opened higher and Treasury yields declined significantly as traders essentially wiped out the chance of another rate hike. They also pulled forward bets of when the Fed will first cut rates into the first half of next year.

The publication noted that equities have rallied in November on bets the Fed is done with rate hikes, with the S&P 500 heading towards its best month since October, 2022.

Bond yields also tumbled, with the 2-year Treasury sinking below 5%.

The drop in inflation suggests that recent monetary policy has been doing its job, which makes the prospect of a “soft landing” ever more likely, according to Richard Flynn at Charles Schwab UK.

Within a day’s release of the US inflation figures, UK inflation tumbled to its lowest in two years, raising expectations that the Bank of England could cut rates by mid-2024.

Reuters said US stocks and bonds have both ripped higher in November “following a months-long wobble,” with inflation data released Tuesday

supporting the view that a turning point is near: consumer prices were unchanged on a monthly basis for October, the first such reading in more than a year and a softer figure than analysts were expecting.

While it could be several months before the Fed pivots to an interest rate-lowering policy, mortgage rate cuts are already happening. CNBC reported on Nov. 9 that 30-year fixed rates slid from 7.86% to 7.61%, which is the largest one-week decline in over a year.

Conclusion

Many including us at AOTH now believe the Fed can pull off what was until only recently viewed as impossible, that is, containing pricing pressures without tipping the economy into recession. This is know as “a soft landing”.

Inflation, which a year and a half ago was threatening double-digits, has been reduced to 3.9% and while it’s not yet at the Fed’s Goldilocks target of 2%, I believe it’s low enough for the Fed to pivot from an interest-rate hiking (tightening) policy to interest-rate reductions likely sometime in early 2024.

Lower interest rates coincide with a lower US dollar which admittedly is still quite high. The US dollar index (DXY) is currently well over 100 and has been since the spring of 2022.

Future weakness in the dollar — the result of much better inflation readings and the expectation of the Fed putting an end to its interest rate-hiking cycle, potentially even lowering rates — bodes well for a number of asset classes: long-dated bonds, gold and other commodities that tend to gain value on a lower dollar, and of course, other currencies that are suddenly attractive compared to the mighty buck.

The beneficiaries of dollar weakness

Of course, there are still headwinds and/or potential black swans that could knock our thesis off course. Quoth the Raven via Zero Hedge provides some examples, including the fact that the stock markets are still overvalued with the S&P multiple around 25x earnings; that geopolitical volatility is high and the West and its foes continue to diverge from one another; the fact that inflation isn’t dead yet although it’s badly wounded; the questionable assertion that market indices are led by only a few stocks, what QTR calls “the magnificent 7”; and the fact that there is still a lot of investment that has still not been reined in. For example the collapse of WeWork and FTX.

I’ve already said I don’t expect the Fed to adhere to its 2% inflation target — maybe something between 2% and 3%. If all its other objectives are met, continuing to raise rates just wouldn’t make sense. As for the 25X earnings evaluation, this has been with us for a long time and I don’t personally believe it’s a signal for a market crash. And we explained above why earnings are so strong.

To us the biggest problem not mentioned by QTR is the debt, and it is for this reason primarily that the Fed can no longer afford to lose money and the Treasury can no longer keep paying the exorbitant amount of interest on the debt.

Remember, the Fed’s loss at the end of the second quarter, 2023 was 17 times its total capital, making it deeply insolvent on a mark to market basis. That’s a result of the plummeting prices of the Fed’s government bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

The Fed can only push interest rates so high without blowing up the Treasury and being forced into an aggressive bond-buying program (QE), thus accelerating inflation.

With 17 cents out of every dollar now going to paying the interest on the debt, it won’t be long before debt servicing costs are the biggest line item, surpassing even the true, bloated defence/ war-making budget.

When the Fed resumes rate-cutting, we predict the dollar will weaken and precious, industrial and battery metals will soar in price.

For gold, it may take awhile for this to happen. Gold prices typically gain when the real rate of interest (interest rate minus inflation) turns negative. Until rates start dropping, if inflation stays around 3.5% real rates will stay positive.

Another product of relatively high rates is a strong dollar. Yield hunters will continue to covet government bonds and US dollars to pay for them if we have positive real rates. Once the dollar starts to weaken, I’d expect commodities to surge especially gold and silver.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.