AOTH Top Metals of 2024 Part 1- Copper – Richard Mills

2024.01.17

2023 was a topsy-turvy year for copper, the red metal buffeted by strong headwinds including a high US dollar, a string of interest rate hikes, and weak demand from China, the largest copper consumer.

It entered last year at $4.12 a pound and exited at $3.88, for a loss of 6.1%. Copper peaked at $4.24 last January, on the back of expectations of a strong rebound in demand from China, which never materialized. It skidded to a 52-week low of $3.51 on May 29.

However, a couple of factors identified by us at AOTH indicate that 2024 will be much better for copper, with the metal potentially knocking on the door of $4 or higher. Most important is supply failing to keep up with demand. The second factor is a weakening of the US dollar if market expectations of monetary easing come to pass.

A majority of respondents to a CNBC Fed Survey said the US Federal Reserve, or central bank, will begin cutting interest rates in June.

Price predictions

Mining Weekly reported last week that BMI has maintained its average yearly copper price forecast at $8,800 per tonne, or $3.99 a pound — higher than the 2023 average of $3.86, due to an anticipated decline in US dollar strength and supply constraints.

According to BMI, global refined copper production will grow by 3.1% this year, supported by Chinese expansion capacity. (To ensure self-sufficiency, China is growing its network of copper smelters, meaning it will start to import much more unrefined copper ore for processing domestically. Read more)

But the copper market will remain tight, says BMI, due to supply issues in Panama. Last year 400,000 tonnes of global copper production was lost when the government abruptly ordered First Quantum Minerals to end operations at Cobre Panama. The $10-billion copper mine had only been running for four years.

BMI forecasts global copper consumption to grow 3.5% to 28 million tonnes in 2024, and for demand to increase from 27 million tonnes in 2023 to 38-million tonnes in 2032, averaging 3.9% yearly growth.

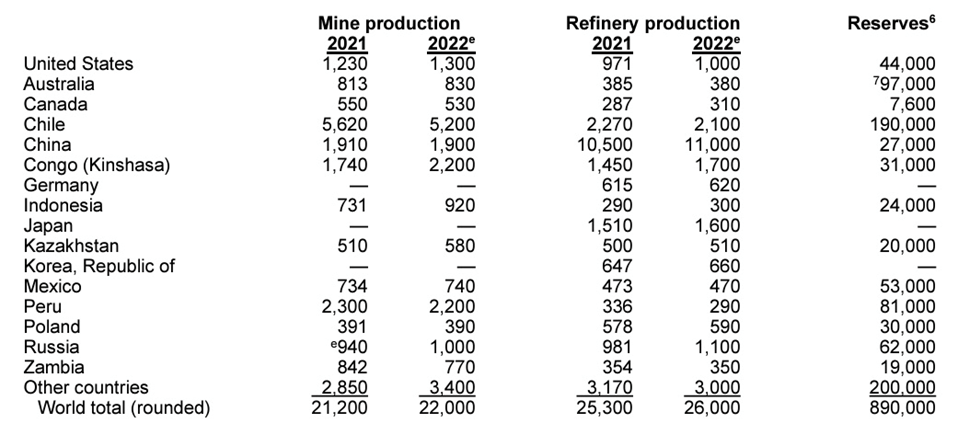

Yet, the US Geological Survey reports supply from copper mines in 2022 amounted to only 22 million tonnes. The 2023 figures aren’t in yet.

Meanwhile, the state-run Chilean Copper Commission, Cochilco, said on Monday it is raising its 2024 copper price projection to $3.85 from $3.75. In a statement, Cochilco said it is more bullish on copper due to “factors like the normalization of monetary policy in the United States,” but mostly due to demand from the energy transition and electric vehicles. (Reuters, Jan. 15, 2024)

The report said it expects Chilean copper production to rise by 5.7% to 5.63 million metric tons in 2024, largely due to more production from Teck’s Quebrada Blanca II project, and 6 million tons in 2025.

The agency foresees global copper production rising 5.8% to 22.79 million tons in 2024 and 23.50 million tons in 2025. Global demand is expected to rise 3.2% to 26.13 million tons in 2024.

Supply constraints

Chile is the world’s largest copper producer, outputting 5.2 million tonnes in 2022 according to the USGS. The country also has the biggest copper-mining company, state-owned Codelco.

Bloomberg wrote last week that Codelco’s production in 2023 was the lowest in 25 years, following a series of setbacks at projects and mines that exacerbated the impact of declining ore quality after decades of underinvestment.

Production for the last three months of 2023 was 358,000 tonnes, less than the 384,000 tonnes produced in the fourth quarter of 2022 alone. Full-year production was 1.324 million tons.

Chile’s copper output has been dented by a long-running drought in the country’s arid north. Cochilco estimates the use of desalination at mines to increase 156% through 2030, with 90% of the desalinated seawater used for copper processing.

Neighboring Peru, which accounts for 10% of world copper supply, has been racked by protests since its former president was ousted in 2022. Last November, a strike at Las Bambas, a copper mine owned by China’s MMG Ltd., threatened ~250,000 tonnes of annual production.

Resource nationalism in Panama has become a real problem for existing and potential mines. Along with the Cobre Panama shutdown, on Dec. 18 it was reported that the Panamanian Ministry of Commerce and Industry canceled Orla Mining’s requests for extending three mining concessions at its Cerro Quema project — despite the fact that the company had already invested $120 million in Panama.

Deficit-bound

Goldman Sachs, via Oilprice.com, has said it predicts a deficit of over half a million tonnes in 2024 due to mining disruptions. “The supply cuts reinforce our view that the copper market is entering a period of much clearer tightening,” analysts at the influential bank wrote.

Major copper producer Anglo American plans to reduce output in 2024 and 2025 to cut costs.

Some of the world’s largest mining companies, market analysis firms and banks are warning that by 2025, a massive shortfall will emerge for copper, which is now the world’s most critical metal due to its essential role in the green economy.

(On July 31, 2023, the US Department of Energy officially put copper on its critical materials list, marking the first time a US government agency has included copper on such a list, following the examples set by the EU, China, Canada, and other major economies.)

The deficit will be so large, The Financial Post stated, that it could hold back global growth, stoke inflation by raising manufacturing costs, and throw global climate goals off course.

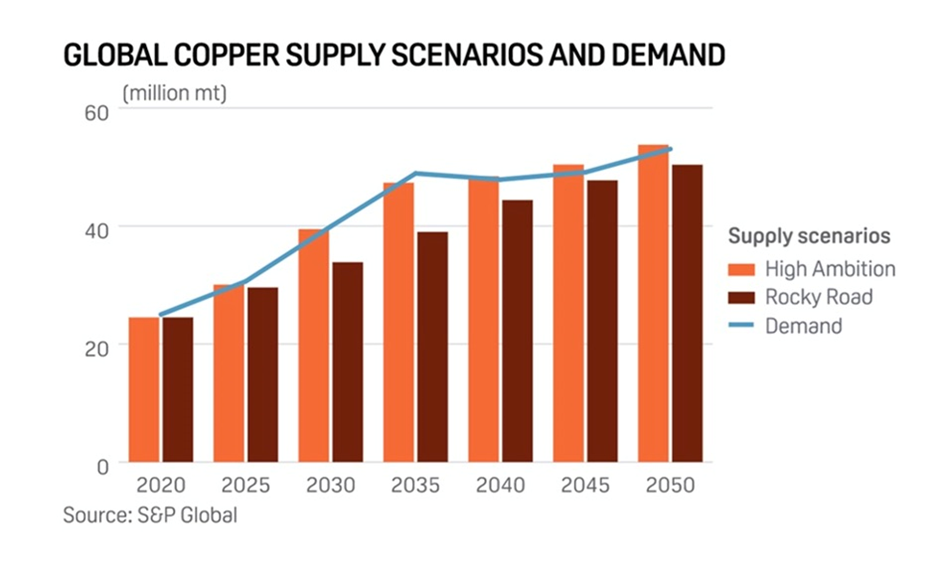

How big are we talking? Well, the speed at which copper demand outpaces supply will depend on the successful meeting of net-zero emission goals. According to a 2022 study by S&P Global, these goals will double the demand for copper to 50 million tonnes annually by 2035. BloombergNEF predicts demand will increase by more than 50% from 2022 to 2040.

“The energy transition is going to be dependent much more on copper than our current energy system,” Daniel Yergin, S&P Global vice chairman, told CNBC. “There’s just been the assumption that copper and other minerals will be there. … Copper is the metal of electrification, and electrification is much of what the energy transition is all about.”

According to consulting firm McKinsey, electrification is expected to create a 6.5 million ton shortfall at the start of the next decade, highlighting a substantial output gap that the mining industry has to address.

Incentive price too low

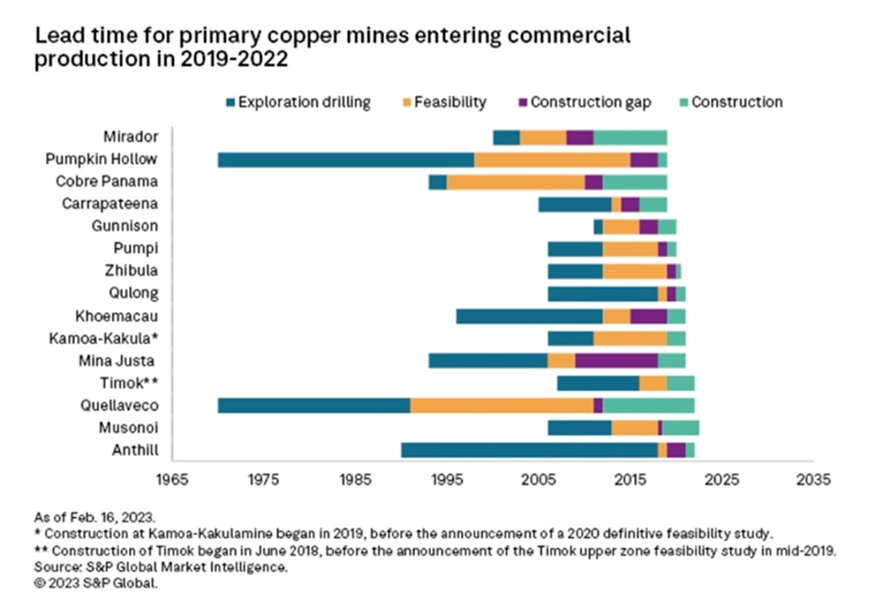

One of copper’s biggest problems is there aren’t enough new mines. Over the past decade, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling 80% since 2010.

Truth is, today’s copper price is too low for new mines to be economical. Incentive pricing in the copper industry is considered to be US$11,000 a tonne — much higher than the current ~$8,300/t.

In fact, it’s probably much higher than that.

Mining magnate Robert Friedland says copper prices have to nearly double to prompt mining companies to build new copper mines whose capex usually runs into the billions. He said forecasts of copper prices reaching $9,000 a tonne in 2024 aren’t enough to incentivize the industry especially in Latin America, which has become more risky.

“We probably need about $15,000 a ton, stable for a long period of time, before the industry can really gear up and build those giant mines,” the Ivanhoe Mines founder and executive co-chairman said in an interview on Bloomberg Television.

Friedland also warns of a copper “train wreck” if supply can’t keep up, stating that prices could jump 10-fold, and cause volatility in the copper supply chain to spike.

Friedland said a combination of factors suggests supply won’t keep pace with demand, including the fact that deposits are getting more expensive and trickier to find, that funding is scarce, and societies have yet to grasp mining’s role in the shift to fossil fuels. (Bloomberg, June 26, 2023)

“When metals are required, the prices go crazy and nobody’s willing to sell them,” he said. “We’re heading into that sort of situation.”

Asia has locked up new copper supply

As we’ve reported, 80% of the foreseeable copper supply is coming from just five mines, but four out of five have offtake agreements with non-Western buyers. That supply is locked up.

The mines are Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC. (by shutting down Cobre Panama, the industry just lost an annual 400,000 tonnes).

In the case of Kamoa-Kaukula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Escondida and Quebrada Blanca are both partially owned by Japanese companies — one can assume that a corresponding percentage of production will be going there.

Analysts do not concern themselves with “who” owns the copper, their only concern is with the amount of global supply. Unfortunately, where it’s going – mostly China, South Korea and Japan – means it’s hardly global supply. Fact is, the West has almost no offtake agreements in place for 80% of the world’s future copper supply.

It’s been previously stated that we need to find 6 million more tonnes of copper, 1 million per year of new copper production if we want to alleviate the deficit — the equivalent production of one Escondida mine each year. Only one of the four mines left standing, Kamoa, has the capability of producing close to that much copper. But Kamoa’s production is going to China.

At AOTH we make a clear distinction between global copper supply and the global copper market. Mined copper that is locked up by offtake agreements should not rightly be lumped in with global supply, because it will never reach the United States, Canada or Europe. Instead, this copper will go straight to smelters in China for use in Chinese industry, to South Korean smelters for South Korean industry, and to Japanese smelters for Japanese industry.

Mined out

Robert Friedland says the average age of the world’s top 10 mines is 95 years.

Operating copper mines are facing dwindling supplies of easy-to-access ore, meaning miners must dig deeper; the increased excavation obviously costs more.

Several large copper mines have mined out all the ore in open pits and are heading underground for the higher-grade, but more expensive to extract material. One example is Oyu Tolgoi in Mongolia, which began underground operations in May.

A mine plan is based on the “cut-off grade”, which is the minimum grade needed to make a unit of rock economic to extract at a given price. Any ore below this grade stays in the ground. When metal prices rise, the mining company makes more per tonne, so it is able to “lower the cut-off grade” and still make a profit. It’s essentially turning what was previously waste rock at old pricing into mineable ore at the new prices.

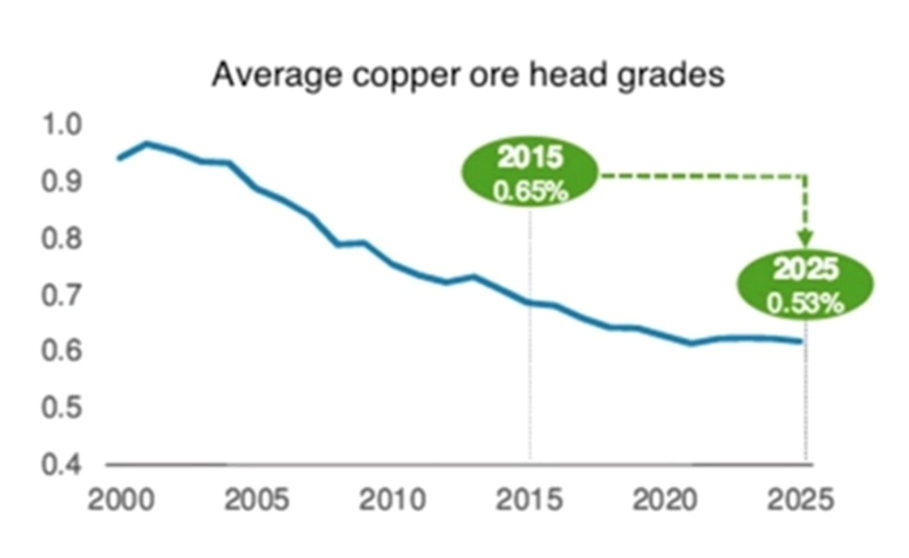

Average copper ore head grades have fallen substantially since 2015 and will continue to trend lower as the chart below shows.

The demand picture

Last fall the International Copper Study Group (ICSG) stated, “An expected improvement in manufacturing activity, the ongoing energy transition and the development of new (semi-manufactured product) capacity in various countries should support higher growth in world refined usage in 2024.”

To achieve net-zero emissions targets, annual copper demand is likely to double to 50 million tonnes by 2035, according to a study by S&P Global. How much red metal actually becomes available is seriously in doubt, as we have outlined in the sections above.

Copper is one of the most important metals with more than 20 million tonnes consumed each year across a variety of industries, including building construction (wiring & piping,) power generation/ transmission, and electronic product manufacturing.

In recent years, the global transition towards clean energy has stretched the need for the tawny-colored metal even further.

Simply put, electrification doesn’t happen without copper, the heartbeat of the global energy economy.

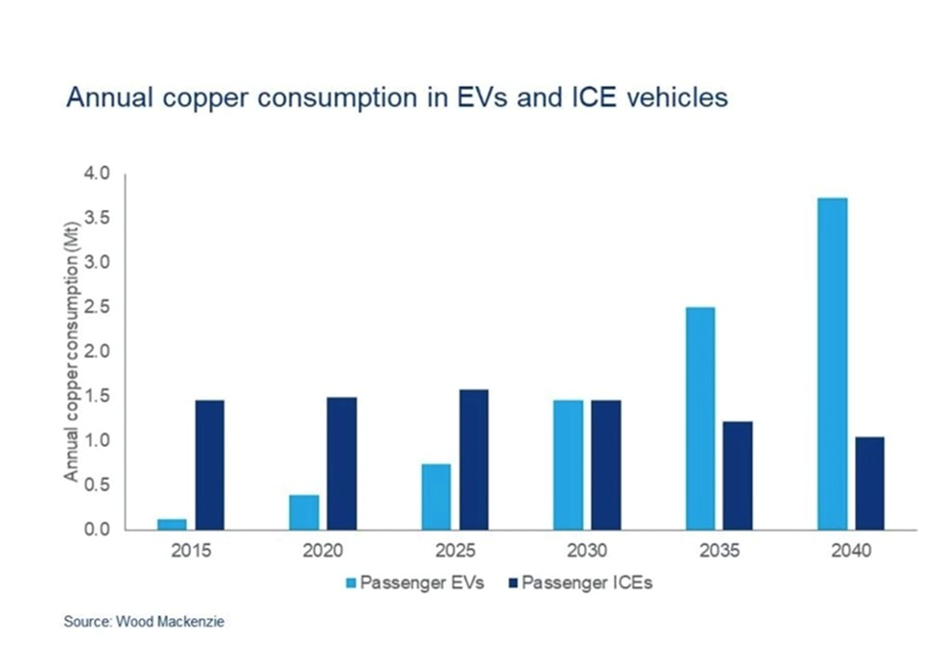

Along with the usual applications in construction wiring and plumbing, transportation, power transmission and communications, there is now an added demand for copper in electric vehicles and renewable energy systems.

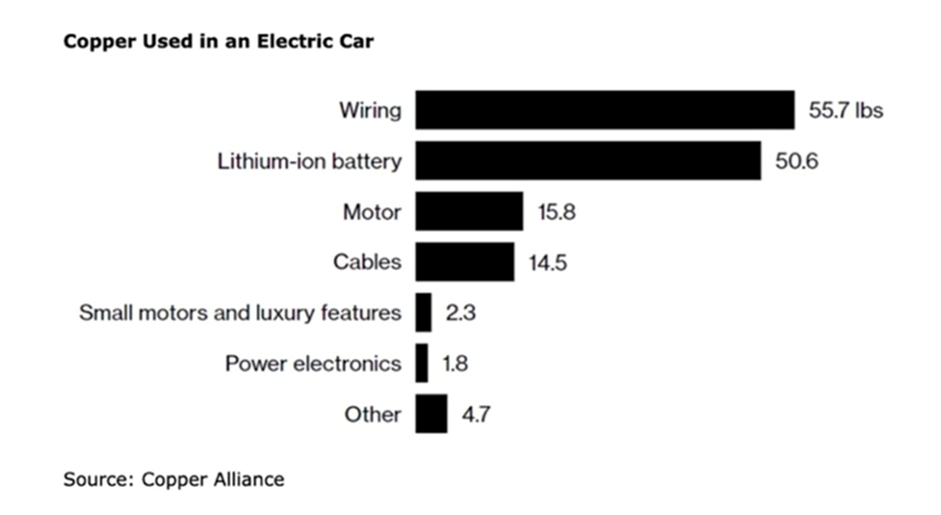

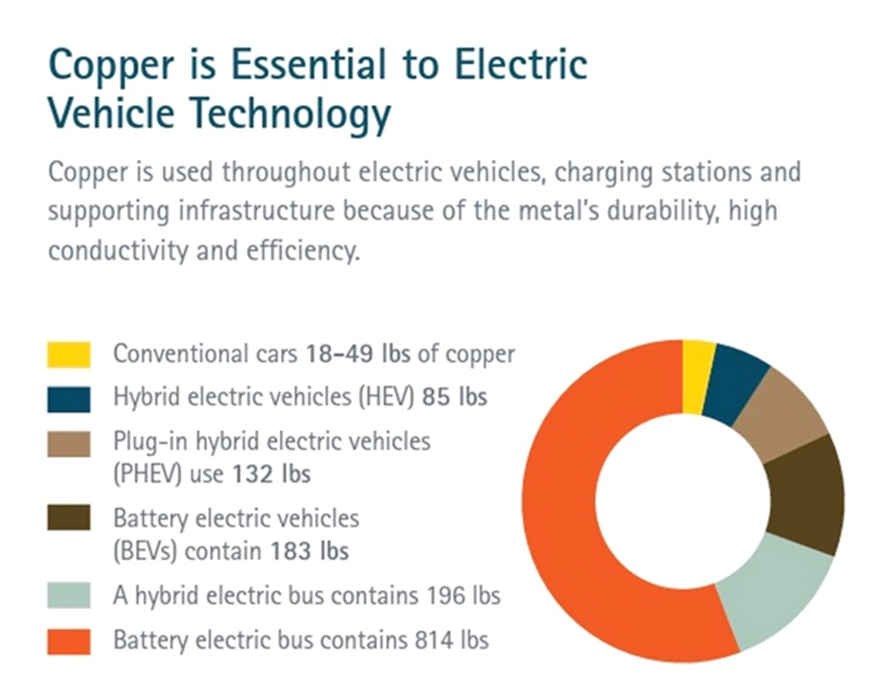

Millions of feet of copper wiring will be required for strengthening the world’s power grids, and hundreds of thousands of tonnes more are needed to build wind and solar farms. Electric vehicles use triple the amount of copper as gasoline-powered cars. There is more than 180 kg of copper in the average home.

To accommodate the demand for electric cars, more than a million new public EV charging stations will be required in the US by 2030. According to a recent S&P Global Mobility assessment, the US must triple its charging infrastructure by 2025, an 8x increase over the country’s current charging capacities. (Business Insider, Jan. 9, 2023)

In the United States, the firm says there are currently 126,500 Level 2 charging stations, which take about five hours to fully charge an EV, and 20,431 Level 3 stations, which will charge an electric vehicle to 80% capacity in 15-20 minutes. There are also 16,822 Tesla Superchargers and Tesla destination chargers.

President Biden has set a goal of 500,000 public charging stations by 2030, a five-fold increase from the 100,000 in place already.

This objective may already be out of date. S&P Global Mobility says that, assuming there are 7.8 million EVs on American roads in 2025, they will require 700,000 Level 2s and 70,000 Levels 3s.

By 2030, if the number of electric vehicles rises to 28.3 million — a realistic assumption — they will require 2.13 million Level 2 and 172,000 Level 3 public chargers, S&P Global Mobility forecasts. This does not include home charging stations drivers will install.

All of this charging infrastructure will require a lot more copper. An average EV contains about 85 kg of the red metal. Charging stations take 0.7 kg (for a 3.3 kW slow charger) or 8 kg (for a 200 kW fast charger), according to the Copper Alliance.

Most of Biden’s new chargers are “Level 2” powered at 6 to 8 kW, so if we assume a copper content of roughly 1.5 kg per charger, an additional 400,000 chargers would need 600,000 kg of copper or 600 tonnes (1 tonne = 1,000 kg).

By 2030, though, S&P expects 28.3 million EVs on US roads, requiring 2.13 million Level 2 and 172,000 Level 3 chargers.

Remember this is only for the United States, and it doesn’t include charging stations homeowners might install in their homes, also requiring copper. It also excludes the copper wiring needed to connect all these new charging stations to renewable energy, and the copper in the renewable energy plants themselves.

According to The Faist Group, in 2021 there were about 375,000 public charging stations in Europe, but according to calculations made by McKinsey, a consulting firm, at least 3.4 million will be needed by 2030.

These numbers mesh with another source that said Europe will require 1.3 million chargers by 2025 and 2.9 million by 2030.

So far the amount of copper required is do-able — 10,000 tonnes is 130 times less than the amount of copper produced by the US in 2022 and 520x less than the copper mined by top producer Chile.

However, if Europe meets its goal of 30 million electric cars by 2030, the amount of copper required @ 85 kg per EV, is 2,550,000,000 kg, or 2,550,000 tonnes. This is nearly double US copper production in 2022 of 1,300,000 tonnes, or almost half of Chile’s annual production.

Remember, S&P Global Mobility forecasts 28.3 million EVs in the US by 2030. That’s 28,300,000 x 85 kg per EV.

Remember we are only talking about copper demand for electric vehicles sold in the US and Europe — we aren’t counting higher EV sales in other countries, along with millions more public and private charging stations to service them, all needing copper, plus supplying all the other copper markets, for construction, power transmission, telecommunications, etc.

This equates to nearly five Escondida mines (the largest in the world), with each producing 1 million tonnes per year. Just to provide enough copper for EVs in the United States and Europe. And not including charging stations, which add another nearly 10,000 tonnes combined.

Now let’s consider copper usage in wind power.

According to the Copper Development Association, a 3-megawatt onshore wind turbine takes up to 4.7 tons of copper, with offshore wind turbines requiring even more. Visual Capitalist states that wind farms use approximately 7,766 pounds of copper per megawatt, while an offshore wind installation uses 21,068 pounds per MW.

More copper tonnage is required for solar power systems, approximately 5.5 tons per megawatt, states the CDA, with the red metal used in heat exchangers, wiring and cabling. An estimated 1.9 billion pounds or 861,826 tonnes (861,826,527 kg/1,000) of copper will be needed to power 262 gigawatts of new solar installations between 2018 and 2027 in North America. This is just over the 830,000 tonnes of copper mined by Australia in 2022.

Copper is also used in energy storage made necessary by the intermittent nature of solar and wind power. According to Visual Capitalist, a lithium-ion battery contains 440 pounds of copper per megawatt, with a flow battery needing 540 lbs/MW.

Last but not least, we have copper usage in electricity transmission.

According to the Copper Alliance, the U.S. electric transmission network contains more than 600,000 circuit miles of lines, of which 240,000 are high-voltage lines. Copper is a key material for transmission and is used in structural frames, conductor lines, cables, transformers, circuit breakers, switches and substations.

As the grid evolves, even more copper will be required. The Copper Alliance notes there is a general trend away from large, remote, utility-scale power plants, and towards thousands of distributed energy resources situated closer to end users. These “microgrids” employ a so-called “intelligent network” that allows adjustments to be made to balance the electrical power in the grid, locally and regionally.

The “smart grid” refers to how the national grid has been developed to recognize blackouts and to respond more quickly. According to the Copper Alliance, The new electrical infrastructure will be more secure, more reliable and more energy-efficient than ever before. And there is no doubt that it will use plenty of copper.

Conclusion

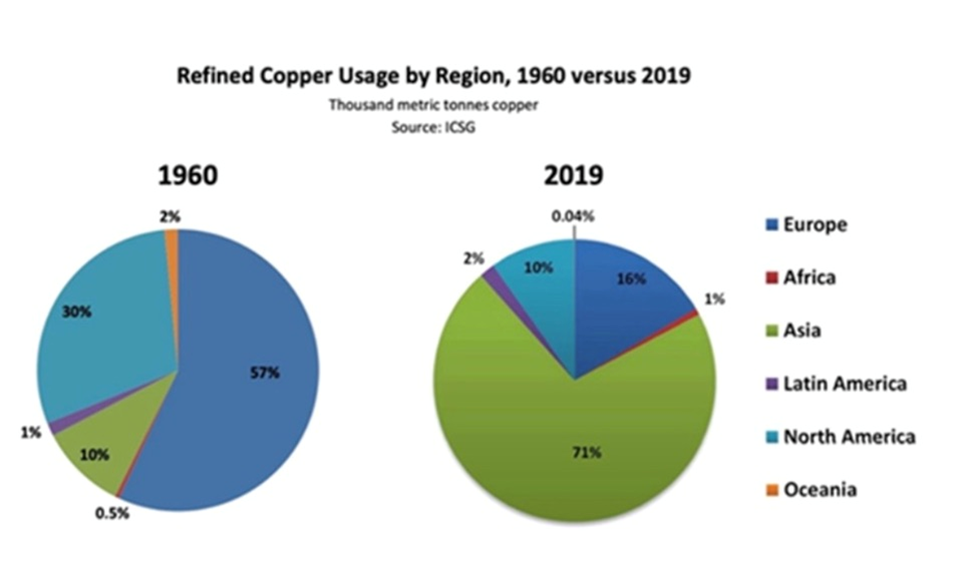

China is going to continue taking a lot of refined copper and wants to switch to importing much more unrefined ore. China is also building out its network of copper smelters, just like it did for iron ore, cobalt, rare earths, lithium, etc. There is no doubt in my mind that China is aiming to become the swing copper producer, and the world’s largest copper exporter, giving it the strongest influence on the copper market. It would effectively become a price maker, not a price taker.

This is yet another example of the global copper market tightening and supporting higher prices.

India has overtaken Japan as the world’s third-largest carmaker last year. Each additional million dollars in Indian GDP equates to 300 kg of growth in copper demand.

Between two new copper smelters opening up next year, India will need 1.4 million tonnes of copper concentrate that will have to be shipped from other countries, almost exclusively from South America.

But the two leading copper producers, Chile and Peru, are having problems meeting production targets due to a combination of global warming, declining ore grades (Chile) and social unrest (Peru).

In Panama, widespread opposition to First Quantum Minerals’ Cobre Panama mine prompted the government to shut it down. First Quantum is taking the country to the International Court of Arbitration to obtain damages for the forced closure. 400,000 tonnes of annual production has vanished.

Now add the 1.4 million tonnes of copper required by India to be used by two new copper smelters opening next year. The result is 1.8 million tonnes of copper that is not coming to the West and should therefore be excluded from global supply.

The Biden administration’s three signature pieces of legislation — the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the CHIPS and Science Act — are costing trillions.

Remember though, that most of this promised money has yet to be spent. When the promises finally translate to shovels in the ground, that will mean thousands of tonnes of additional copper demand, for things like smart grids, nuclear power plants, electric vehicles and EV charging station, and blacktop infrastructure.

Copper is already facing major supply challenges, including strikes, resource nationalism, global warming (droughts, water shortages), declining ore grades, depleted orebodies, a lack of new mines, and regulatory delays in building new ones.

Moreover, the current copper price is too low to incentivize new mines.

Asian countries are switching to ore imports as they expand refinery/ smelting capability. This does not bode well for Western copper supplies. Remember, for the foreseeable future, copper supply is 80% concentrated in just five mines, all of which have major off-take agreements with South Korea, Japan or China. For instance, 100% of the massive Kamoa mine’s offtake will go to China.

As for producing copper domestically, the Canadian and US governments haven’t made it any easier for copper mining companies. About half of America’s scrap metal is sent overseas for processing because the country doesn’t have enough smelters. The Biden administration has prevented or stood in the way of new mining properties in Minnesota, Arizona and Alaska. Even when mines are green-lighted, in North America it can take up to 20 years to get from discovery to production.

Commodity analyst predictions are usually wrong about copper supply, often predicting a glut in the market for the ubiquitous metal used in everything from piping and wiring in houses, to electrical transmission lines to components of electric vehicles.

Every year there are between 800,000 and 1 million tonnes of copper that fails to make it from mine to market. When we add this “missing” copper to the 1.8 million tonnes of copper that has already disappeared from the global copper market, we get between 2.6 and 2.8 million tonnes of under-supply, the equivalent of roughly 12% of global copper supply. (2022’s mine supply = 22Mt)

Wood Mackenzie analysts estimate a 6-million-ton shortfall by next decade, meaning six Escondida-sized mines would need to come online within that period — this is 100% NOT going to happen, not even close.

A report by another consultancy, McKinsey, found that electrification is projected to increase annual copper demand to 36.6 million tonnes by 2031, with supply projections offering a pathway to 30.1Mt, leaving 6.5Mt of capacity to be found.

I pose the question: Where are we going to find the copper?

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.