A tale of two depressions

2020.05.02

As the coronavirus continues to hammer state and provincial economies, politicians are being forced to consider whether lockdown “cures” are worse than the disease. Pressured by the Trump administration, and in some cases the public, several US states are planning a re-opening, or partial re-opening of their economies, sometime in May.

About half of Canadian provinces and territories are also in the midst of a re-start of some description; among those still locked down are British Columbia, Alberta, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland/ Labrador.

The question weighing on the minds of both health officials and economists, is whether letting up on social distancing restrictions will cause the number of covid-19 cases to spike, thereby setting back virus containment efforts and the timeline of economic recovery. Yet regardless of what comes next, it doesn’t take a lot of analysis to see we are already in a heap of trouble.

On Tuesday the Globe and Mail reported the Canadian economy is likely in its deepest recession on record – hit by a one-two punch of the covid-19 pandemic and an oil price collapse even worse than 2014.

If their predictions come true, it would mean Canada is already in the ugliest recession since records started being kept in 1961.

In the US, first-quarter GDP shrank by 4.8%. Economists said it was the biggest first quarter drop in gross domestic product since 2008.

“Shelter in place” orders to slow the spread of the coronavirus have throttled the engine of the economy. Consumer spending, which makes up 70% of US GDP, fell 7.6%, the biggest retreat since 1980. Spending on durable goods tumbled 16.1% and expenditures on services slumped 10.6%.

Last week another 3.6 million Americans filed for unemployment, bringing the total thrown out of work over the past six weeks to about 30 million, a fifth of the workforce.

As bad as it was, Q1 was only a prelude for what is to come. According to Marketwatch, the economy is likely to decline by 25% or more in the second quarter, with some economists projecting a record 40% tumble.

Globally, the International Monetary Fund warned the world economy will contract by 3% this year, the fastest pace in decades.

The IMF said both advanced and developing economies are expected to fall into recession, with the UK economy shrinking by 6.5% in 2020, the biggest downturn in a century, and the US economy contracting by 5.9%, the worst annual decline since 1946. Australia will enter its first recession since 1991, and China’s anticipated 1.2% growth would be the slowest since 1976. In some countries the jobless rate will surpass that of the financial crisis.

If the pandemic fades in the second half of this year, the Fund predicts global growth will rebound by 5.8% next year but warns that growth in advanced economies will not get back to pre-virus levels until at least 2022. A second wave of covid-19 in 2021 would knock an additional 8 percentage points off global GDP and trigger a downward spiral in heavily indebted economies, said the IMF, via the BBC.

All of this gloom and doom has a lot of pundits uttering the dreaded “D” word for depression, or at the very least, a deep recession that could eclipse anything we’ve seen since the Second World War, lasting not months, but years.

In our last article we asked: How much of an economic reckoning could we face from the coronavirus pandemic? Here we want to know: Were we heading for a crash even without the coronavirus? The affirmative answer to that question invites a comparison with the lead-up to the Great Depression. The parallels are eery. What can be done to get us out of this mess? Again, the lessons from the Depression are instructive.

1929 vs 2019

Underpinned by a wave of urbanization, the “Roaring Twenties” were a decade of dramatic social and political change. For the first time in history, more Americans lived in cities than on farms. The newly affluent found they had more money to spend on consumer goods, popularized by advertising and chain stores. Within a decade, the nation’s wealth had doubled.

For a growing cadre of “nouveau riche”, symbolized by characters in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel, ‘The Great Gatsby’, the ‘20s presented seemingly endless opportunities to get even richer. As History.com puts it,

The stock market, centered at the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street in New York City, was the scene of reckless speculation, where everyone from millionaire tycoons to cooks and janitors poured their savings into stocks. As a result, the stock market underwent rapid expansion, reaching its peak in August 1929.

By then, production had already declined and unemployment had risen, leaving stock prices much higher than their actual value. Additionally, wages at that time were low, consumer debt was proliferating, the agricultural sector of the economy was struggling due to drought and falling food prices and banks had an excess of large loans that could not be liquidated.

The American economy entered a mild recession during the summer of 1929, as consumer spending slowed and unsold goods began to pile up, which in turn slowed factory production. Nonetheless, stock prices continued to rise, and by the fall of that year had reached stratospheric levels that could not be justified by expected future earnings.

We all know what happened next. The stock market crash of October 1929 sent Wall Street into a panic and wiped out millions of investors. The depression that followed has been well documented. What has not been written about, until now, is how similar recent events were, to the months leading up to ‘Black Thursday’ – Oct. 24, 1929.

In October 2019 there was no stock market crash, but there were certainly a large number of indications the US economy was moving towards recession.

The possibility had been mooted by a number of sources for months, evidenced by an inverted yield curve, investors holding a high percentage of cash instead of stocks, and unsustainable levels of debt.

The coronavirus could therefore be seen as the straw that broke the camel’s back, weighed down by the longest economic expansion in US history.

In December, North American investors were divided between those who believed the decade-long stock market bull was going to keep running into the 2020s, and investors who, wary of something terrible happening, were hoarding cash and gold.

Unemployment was at its lowest in 50 years, wages in 2019 grew by 3.1%, and stock markets kept rolling along.

Yet something was wrong, and we at AOTH knew it.

The most important recessionary signal was a drop in consumer spending, which makes up 70% of the US economy. In September, 2019, US retail sales fell for first time in seven months, as households slashed spending on building materials, online purchases, and especially cars.

Three months later, sales at clothing stores declined the most since January 2009.

The coronavirus has deepened consumers’ fear of racking up any large purchases, like a new home or car. For the first quarter of 2020, consumer spending fell 7.6%, the biggest retreat since 1980.

During the Depression there was also a major drop in consumption, along with widespread poverty, hunger and political unrest. Unemployment peaked in 1933 at 25% and remained in the double digits until 1941.

The huge numbers of jobless is without a doubt the most disturbing similarity between the coronavirus downturn and the Depression.

Last week another 3.6 million Americans filed for unemployment, bringing the total thrown out of work over the past six weeks to about 30 million.

As bad as it was, Q1 was only a prelude for what is to come. According to Marketwatch, the economy is likely to decline by 25% or more in the second quarter, with some economists projecting unemployment could reach 30%.

Business investment was also under pressure in the lead-up to covid-19.

In 2019 US companies cut back on investment due to reduced exports and disruptions to the global economy from the US-China trade war. January 2020 marked the second straight month of decreased industrial production. The IHS Markit purchasing managers index (PMI) fell to a three-month low.

Reuters confirms that manufacturing was already struggling, due to the trade war with China, well before the coronavirus landed on US shores.

In March, US manufacturing output dropped the most in over 74 years due to broken supply chains owing to covid-19 business closures, layoffs and interruptions to normal operations. April’s data signed an unprecedented contraction in production across the US manufacturing sector, linked to measures to contain the covid-19 outbreak.

Like in 1929, the stock market in 2019 was bubbly, US agriculture was in trouble, and debt levels were becoming unmanageable.

According to a feature story in USA Today, over 450 farmers from nine Midwestern states committed suicide between 2014 and 2018. Behind each sad story are some stark figures: key commodity prices including soybeans, corn and wheat have fallen about 50% since 2012; farm debt is a third higher than in 2007; US soybean exports to China dropped 75% from 2017-18, amid trade war tensions; bad weather prevented farmers from planting nearly 20 million hectares in 2019. Droughts are regular occurrences in US farm-belt states, including Texas and the MidWest, not unlike the barren fields of Oklahoma that prompted the great migration westward, documented in John Steinbeck’s ‘The Grapes of Wrath’.

And then there’s debt. Mountains of it. Debt didn’t cause the Great Depression but we have shown the debt bubble to be the biggest risk to the current global economy.

Almost 19 trillion dollars of debt is owed by companies that don’t earn enough to cover interest payments. A recent analysis by the UN Conference on Trade and Development found that in 2018, total debt across developing countries amounted to over twice their combined GDP – the highest it’s ever been. Nearly three-quarters of that debt is held by non-financial corporations and owed to external creditors in foreign currencies.

This cannot go on forever. It’s not a stretch to envision a scenario whereby the world’s reserve currency, the US dollar, collapses under the weight of unmanageable debt, triggered say, by a mass offloading of US Treasuries by foreign countries, that currently own about $6 trillion of US debt. This would cause the dollar to crash, and interest rates would go through the roof, choking consumer and business borrowing. Import prices would skyrocket too, the result of a low dollar, hitting consumers in the pocketbook for everything not made in the USA. Business confidence would plummet, mass layoffs would occur and growth would stop.

Between 2008 and 2015 the US Federal Reserve bought trillions of dollars worth of T-bills and mortgage-backed securities, keeping interest rates near zero percent, but making the US debt balloon from $900 billion to $4.5 trillion.

Five years later the US national debt stands at $24 trillion and counting. In January the World Bank warned of the risks of a global debt crisis – pointing to the latest of four waves of debt accumulation over the past 150 years.

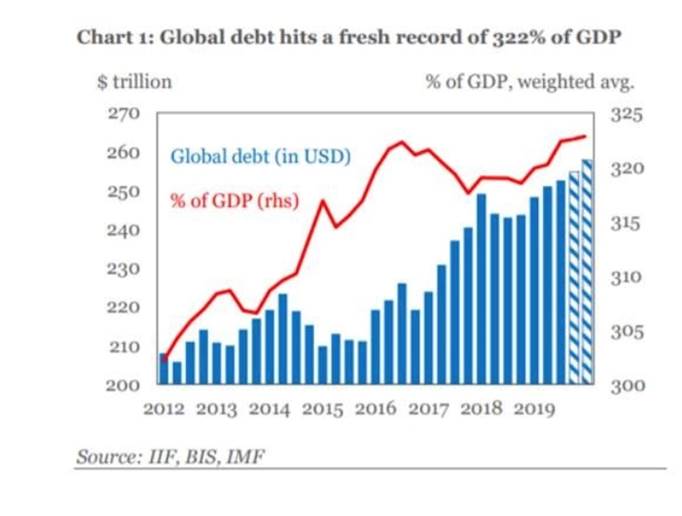

Encouraged by lower interest rates, governments went on a borrowing binge as they ramped up spending. In the first quarter of 2019, global debt hit $246.5 trillion, reversing an earlier trend of debt reduction.

Excess debt is a brake on aggregate demand. Over the last 13 years, global debt has increased by $128 trillion, but GDP has only risen by $27 trillion. Ie. countries borrowed five times more than their economies produced.

How they’re different

History.com notes how America’s adherence to the gold standard, which joined countries around the world in a fixed currency exchange, helped spread economic woes from the United States throughout the world, especially Europe.

Each US dollar, the world’s reserve currency, was based on 1/35th of an ounce of gold ($35.20 an ounce).

On August 15, 1971, US President Nixon ended the convertibility of the dollar into gold. With gold demonetized, the Fed and the world’s central banks were now free from having to defend their gold reserves and a fixed dollar price of gold. The era of Bretton Woods was over.

The glaring difference between the coronavirus crisis, which in the absence of a rapid return to normal, is leading either to a deep global recession or, God forbid, a depression, is that today’s central banks are free to “print their way out of it”. In other words, they can pursue all the economic stimulus they want, by cranking up their printing presses, minting more units of currency to backstop ambitious bail-outs, and engaging in “quantitative easing” to purchase bonds and other assets that will help the banks to lend out more to businesses needing their help during the crisis.

During the Depression, banks could only lend up to the equivalent amount of gold sitting in their vaults. That’s a major restriction which prevented the kind of multi-billion-dollar bail-outs that are common in today’s fiat monetary system. The advantage, of course, is that gold-backed currencies prevent central banks from dumping dollars or other units of currency into their respective financial systems, risking hyper-inflation.

Consumer spending, a critical part of the economy both today and back in the 1930s, took a heavy hit during the Depression due to the number of unemployed which peaked at one-quarter of the workforce in 1933. Today, within six weeks, a gut-wrenching 30 million have been left jobless by government-ordered business closures owing to covid-19. Their freedom to find work, make money and spend it in the economy is being curtailed by social distancing restrictions. Depression-era jobless did not have a virus preventing them from returning to the workforce.

Finally there is the issue of leadership. Franklin D. Roosevelt will be forever associated with the New Deal that helped rescue America from the Depression. In 1932 Roosevelt, a Democrat, won an overwhelming victory in the presidential election. History.com describes how FDR wasted no time in putting the US economy on a road to recovery:

By Inauguration Day (March 4, 1933), every U.S. state had ordered all remaining banks to close at the end of the fourth wave of banking panics, and the U.S. Treasury didn’t have enough cash to pay all government workers. Nonetheless, FDR (as he was known) projected a calm energy and optimism, famously declaring “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Roosevelt took immediate action to address the country’s economic woes, first announcing a four-day “bank holiday” during which all banks would close so that Congress could pass reform legislation and reopen those banks determined to be sound. He also began addressing the public directly over the radio in a series of talks, and these so-called “fireside chats” went a long way towards restoring public confidence.

During Roosevelt’s first 100 days in office, his administration passed legislation that aimed to stabilize industrial and agricultural production, create jobs and stimulate recovery.

In addition, Roosevelt sought to reform the financial system, creating the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to protect depositors’ accounts and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to regulate the stock market and prevent abuses of the kind that led to the 1929 crash.

Compare this to President Trump’s performance during the pandemic.

Seeing the coronavirus as a threat to the US economy that could hamper his chances for re-election, Trump’s first reaction was denial. Between January and March he repeatedly downplayed the threat the coronavirus posed to US citizens. Numerous opportunities to block its spread weren’t taken, allowing it to pick up speed.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, between March 1 and March 31, the number of covid-19 cases went from 30 to 187,101, an increase of over 6,000%!

Interviewed on Jan. 22, the day after the first American case had been announced, Trump was asked, “Are there worries about a pandemic at this point?” He responded: “No. Not at all. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”

In February, when stock markets started reacting to the spread of the coronavirus in Asia, from China to Japan, South Korea and Iran, Trump saw it not as a time to gird against a possible pandemic, but a time to gamble, to roll the dice.

The President downplayed requests by states for more resources to combat the virus, including badly hit New York. Despite having practically unlimited procurement powers during the declared state of emergency, Trump told New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, “I don’t believe you need 40,000 or 30,000 ventilators.”

And notwithstanding advice from epidemiologists to invoke social distancing measures and lockdowns, Trump famously said he expected church pews to be full on Easter Sunday. It was just one of several statements the unconventional, often anti-science president has made, based on hunches, limited reasoning and outright denial of scientific facts.

Trump denied he had ever seen two key memos about the coronavirus, written and circulated in January by Peter Navarro, his top trade advisor, and known China hawk.

The memos warned the covid-19 virus had the potential to kill hundreds of thousands of Americans, and cost the US economy trillions, unless tough actions were taken immediately.

When asked to clarify why the memos appeared to contradict his saying that “no one could have known” about the coronavirus, Trump told reporters gathered at a daily press briefing, “I didn’t see them. I didn’t look for them.”

Getting out

Roosevelt’s New Deal provided a template for focused government spending programs that target large infrastructure projects. Among its programs that helped the United States to recover from the Great Depression were the Tennessee Valley Authority, which built hydroelectric projects in the hard-hit Tennessee Valley region, and the Works Progress Administration, a jobs program that employed 8.5 million people from 1935 to 1943.

History.com recalls the buoyant effects of the New Deal on the American economy:

After showing early signs of recovery beginning in the spring of 1933, the economy continued to improve throughout the next three years, during which real GDP (adjusted for inflation) grew at an average rate of 9 percent per year.

A sharp recession hit in 1937, caused in part by the Federal Reserve’s decision to increase its requirements for money in reserve. Though the economy began improving again in 1938, this second severe contraction reversed many of the gains in production and employment and prolonged the effects of the Great Depression through the end of the decade.

In an earlier article we suggested how a “Debt Jubilee” retiring the world’s $246 trillion debt burden, combined with a massive infrastructure building program, could kickstart the global economy flat-lined by the coronavirus.

Governments, relieved of their crushing debts, would be free to offer generous social programs without having to hike taxes. They could also finally dedicate the vast sums of tax dollars required to address global warming, and the trillions of dollars worth of investment needed to close the global infrastructure gap. That means making funds available for worn-out highways, bridges, airports, sewage systems, new money for subway systems, buses, new recreation centers, etc.

Released from the thumb screws of debt, consumers, businesses and governments are free to spend and borrow, at rock-bottom interest rates. It’s practically free money, and best of all, it comes with no strings. Over a short period of time, the world economy starts growing again.

The world faces a global infrastructure deficit of $94 trillion. To close the gap, annual infrastructure spending would need to rise by 0.5%, according to a report from the G-20-backed Global Infrastructure Hub.

The Federation of Canadian Municipalities says Canada needs to spend $2 billion a year, to meet current infrastructure needs.

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, from 2013 to 2017 (when its last Infrastructure Report Card came out), there has been no improvement in bridges, roads, drinking water, energy, aviation and dams. Estimates are it will take $4.6 trillion by 2025 to bring US infrastructure up to an acceptable standard.

Dam-building could make up the bulk of a US-Canada infrastructure build-out.

Canada has a lot of fresh water – 37 million Canadians own 7% of the world’s renewable supply. We’ve been blessed with an abundance of the world’s most important resource – a resource we’re going to eventually have to share with our southern neighbor.

The Great Recycling and Northern Development (GRAND) Canal of North America (GCNA) was designed by Newfoundland engineer Thomas Kierans to alleviate North America’s freshwater shortage problems.

The GNAC would collect fresh water run-off into James Bay by means of a series of outflow-only, sea level dikes-constructed across the northern end of James Bay. These dikes would capture the fresh water before it mixes with the salty water of Hudson Bay and create a new source of fresh water equivalent to 2.5 times the flow over Niagara Falls.

Canals would be built to transfer the water from James Bay into the Great Lakes and from the Great Lakes canals and pipelines move the water to areas in the US.

Conclusion

It’s still early days in the covid crisis but already we are seeing the economic devastation wrought by the first six weeks of government-ordered lockdowns, business closures and social distancing measures.

The longer it goes on, the deeper national economies will fall into recession, or even depression. Many governments are stuck between a rock and a hard place, wanting desperately to re-open their economies but understanding that lifting restrictions too soon could invite a second wave of infections, knocking back virus containment efforts to square one.

However, if re-opening is done right, we see every possibility for a reasonably fast recovery, especially if the lifting of restrictions is combined with debt forgiveness and infrastructure programs that help to put people back to work and get them spending again.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.