A Déjà vu in Pacific Northwest as atmospheric river forces highway closures and evacuations – Richard Mills

2025.12.12

The nightmare of 2021 has come back to haunt residents of the Fraser Valley in southern British Columbia and northern Washington State, as an atmospheric river dumps record rain on the region, closing highways and border crossings, causing rivers to overflow their banks, and triggering evacuation orders and alerts due to widespread flooding.

The system moved in on Monday, Dec. 8, dropped the most precipitation on Dec. 10, and is expected to last until early next week.

A CBC News summary of the situation said flooding in the Fraser Valley, just east of Vancouver, was expected to peak Friday, with more rain on the way Saturday night

The flooding in the Fraser Valley was caused by the Nooksack River in Washington State overflowing its banks. It’s the second time in four years that the Nooskack has flowed northward across the border.

As of 1:41 pm on Friday afternoon, Highway 1 is closed in both directions between Sumas Road and No.3 Road; nearly 500 properties in Abbotsford are under evacuation order and 1,000 are on alert; all schools in Abbotsford and Chilliwack are closed; Environment Canada has issued a special weather statement for more rainfall this weekend and into next week.

Residents are dealing with up to 1.5 meters of floodwater in their yards, garages and homes.

As far as damage to infrastructure, BC’s Transportation Ministry says Highway 3 connecting Hope to Alberta has been “severely undermined” and is closed. About 23 sites along that roadway have suffered damage from rockfalls, debris and culvert undermining, CBC News reported.

Over 160 farms in the Fraser Valley are under evacuation order or alert, although livestock is considered safe.

Comparisons to 2021

The situation is drawing comparisons to November 2021, when back-to-back atmospheric rivers slammed into the region.

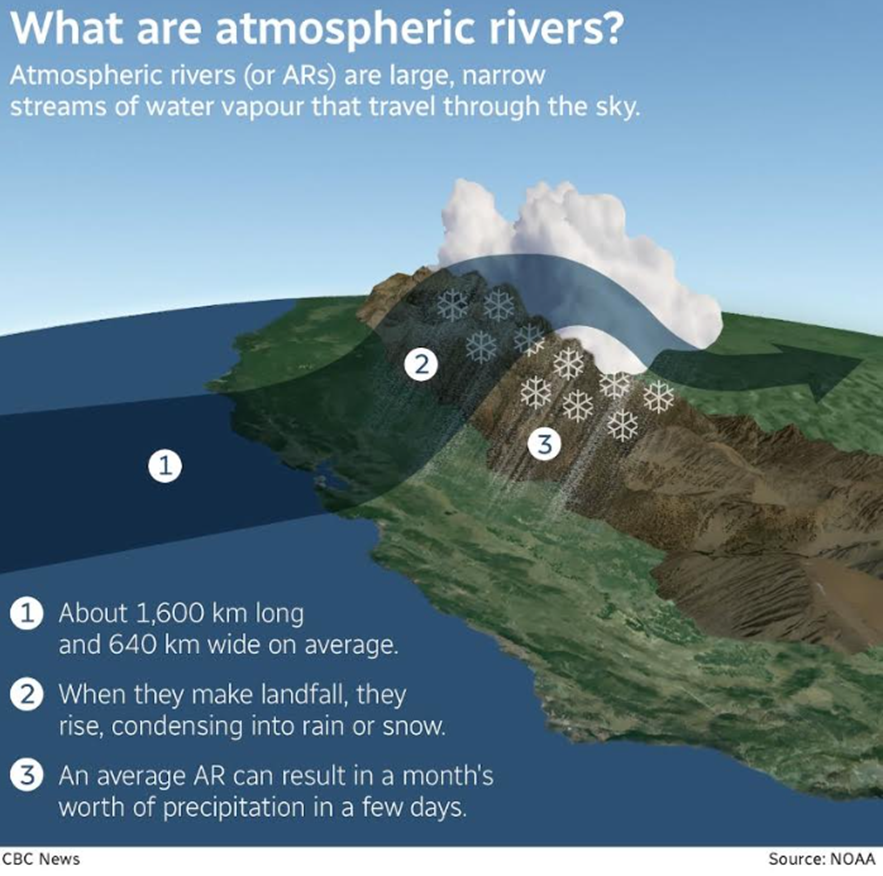

NASA describes atmospheric rivers as long, narrow corridors of water vapor that travel vast distances above the ocean from warm, tropical regions to higher latitudes, where they often release their moisture as rainfall when they reach land areas.

2021 flooding in southern British Columbia caused up to $5 billion in uninsured losses and $675 million in insured losses, according to a damage estimate caused by extreme weather that year, put out by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

The CCPA report said total damages ranged from $10.6 billion to $17 billion, including uninsured wildfire losses of $501 million, making it the most expensive natural disaster in Canadian history.

Five people died in British Columbia, including four caught in a mudslide on Highway 99, the road to Whistler. One death occurred in Everson, WA, where a man was swept away by floodwaters.

The event reportedly caused the deaths of 628,000 chickens, 420 dairy cattle and 12,000 pigs. 110 beehives were submerged, killing an estimated 3 million bees. It is considered the worst agricultural disaster and animal welfare crisis in the province’s history.

One of the main differences between this atmospheric river and the ones in 2021 is that Washington State has been hit harder than BC.

As of Thursday, Dec. 11, more than 100,000 people in the neighboring state were forced to evacuate.

Governor Bob Ferguson declared a statewide emergency due to widespread flooding. He also activated the National Guard.

Global News reported flooding has affected communities north and south of Seattle, with some people needing to be rescued.

Ferguson also said Thursday he had an emergency call with FEMA to request an expedited emergency declaration from the federal government. FEMA stands for Federal Emergency Management Agency.

An official with the Washington State Emergency Management Division said the water coming through the levees was at about the record flood level. The official added “we’re still expecting to see about two feet higher than record flood level. It’s going to be most likely worse than you experienced back in 2021.”

Meteorologist Brian Proctor from Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) told The Daily Hive one reason that British Columbia avoided something worse is that a lot of the river basins in Washington State are smaller than those in southwest BC.

Also, the Dec. 10 event, while inflicting heavy rain, was nowhere near as bad as in 2021. Chilliwack, for example, saw its 22nd wettest day compared to its second wettest day ever in November 2021.

Procter told The Daily Hive “we’re not out of the woods yet,” with another system coming on shore Friday, with the majority impact of the storm likely to be on northern Vancouver Island and the Central Coast.

Heavier amounts of rain are expected in Washington State, “so that Sumas Prairie area is still going to be very problematic, with the Nooksack River draining northwards…,” Procter said.

Connie Chapman, executive director of water management with the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship, was quoted in Castanet saying that the amount of water coming out of the Nooksack River is similar in volume to levels seen in 2021 and in 1990.

But she said there are a number of variables that may change the severity of the scenario, including a much shorter duration of flooding and easing rainfall.

“Though the volume is the same amount, that is moving at that instantaneous rate, the time period is shorter than what was seen in 2021 and 1990,” Chapman said.

Minister of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness Kelly Greene said a “lot of lessons” were learned during the 2021 floods, and a number of improvements have been made.

Greene said those improvements include greater communication and coordination between communities, the province and Washington State in the U.S., improved monitoring stations, and breaches in a dike in the Sumas area have been repaired.

“We are in a much more knowledgeable spot than we have been historically and that’s helping with preparation,” she said.

Greene said crews are on standby to assist local governments if the situation grows beyond their capacity, and pre-positioned flood control resources, including over $5 million in sandbags, are available as well.

(read the Conclusion to see what hasn’t been done — Rick)

Peak of the storm

At the peak of the storm on Wednesday, the Ministry of Transportation closed major highways between the Lower Mainland and the Interior due to flooding, falling rock and debris, and high avalanche hazards.

The Fraser Valley Regional District issued an evacuation order for eight properties along the Chilliwack River, an evacuation alert for several properties on Chilliwack Lake Road, and declared a local state of emergency.

This followed a flood warning issued earlier on Wednesday by the B.C. River Forecast Centre. A travel advisory was issued for areas in the Fraser Valley where there is risk of flooding. (Global News)

On Global TV News, meteorologist Kristi Gordon pointed out an orange warning for rainfall — issued when severe weather is likely to cause significant damage, disruption or health impacts — for the central Fraser Valley, including Chilliwack and Hope. The lesser yellow alert covered most of the Lower Mainland and the area north of Hope.

Environment Canada warned the system would bring up to 110 millimeters of rain in 24 hours.

The Fraser Valley Regional District declared a State of Local Emergency (SOLE) for FVRD Electoral Area E, along with evacuation orders and alerts.

The B.C. River Forecast Centre upgraded the Flood Watch to a Flood Warning for Fraser Valley East. A Flood Warning means that river levels have exceeded bankfull or will exceed bankfull imminently, and that flooding of areas adjacent to the rivers affected will result.

The next day, the Vancouver Sun reported 17 rainfall records were broken, including 134.2 mm in Hope, beating the 2004 record of 74.5 mm. Other hard-hit areas were Agassiz and Chilliwack (both 91.8 mm) and Abbotsford (86.2 mm).

The yellow and orange warnings were lifted Thursday morning but Environment Canada cautioned that more rain is on the way.

Fraser Valley Today reported Thursday that some localized flooding has occurred in Greendale, between Hopedale West and Spurline Road, and on Sumas Prairie Road in downtown Greendale. High ditches have caused some localized flooding in East Chilliwack along McGuire Road, Upper Prairie Road and Patterson Road…

Chilliwack declared a state of emergency at 2 pm and issued an evacuation order for two properties on Marble Hill Road after a debris slide caused by heavy rain.

Is global warming a factor?

Atmospheric rivers aren’t new. According to CBC Radio, They usually begin life in the tropical ocean regions near the equator, and can bring large masses of warm air and water to areas like North America’s west coast.

As the rivers cross from the ocean to the land — particularly to mountainous regions like the B.C. coast — the vapour condenses into precipitation, sometimes dumping a month’s worth of rain or snow in a matter of days.

The term was first coined in 1998 by two MIT researchers, but CBC Radio says they have been observed before then.

Some believe that ARs are being made worse by global warming. It is certainly true that the warmer the air is, the more water vapor it can carry. According to a 2018 study, atmospheric rivers that reach the BC coast are expected to become up to 25% wider, 25% longer and 50% more intense than before.

The resulting rain events will also become longer, potentially lasting four or five days as opposed to the usual one or two, CBC Radio reports from the study in the journal ‘Geophysical Research Letters’.

Compounding the threat are increasingly severe wildfires, which incinerate trees, leaves and the forest floor that would otherwise absorb moisture and precipitation.

While atmospheric rivers are commonly seen in the extratropics, a region between 30 and 50 degrees latitude in both hemispheres that includes most of the continental US, southern Australia and Chile, a recent study shows that atmospheric rivers have been shifting poleward over the past four decades.

Yahoo News reports that In both hemispheres, activity has increased along 50 degrees north and 50 degrees south, while it has decreased along 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south since 1979. In North America, that means more atmospheric rivers drenching British Columbia and Alaska.

One main reason for this shift is changes in sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific. Since 2000, waters in the eastern tropical Pacific have had a cooling tendency, which affects atmospheric circulation worldwide. This cooling, often associated with La Niña conditions, pushes atmospheric rivers toward the poles.

Conclusion

We can’t stop atmospheric rivers from happening, but we can take steps to mitigate the damage. This includes strict floodplain laws to limit construction on these vulnerable areas, upgrading dikes and drainage to handle more extreme events, and providing early warning systems so that residents can prepare for the worst.

The Nooksack River in Washington State is a problem that needs to be fixed. The river overflowed its banks in 2025, 2021 and 1990, crossing the border and causing widespread flooding on the Sumas Prairie.

While an extensive dike system and a pump station in Abbotsford protects the prairie from Nooksack overflow, work on upgrading the facility, including constructing protective walls and improving the machinery, is not yet complete. How’s that for government inefficiency?

“One of the key things is the building of flood-resilient infrastructure,” Elise Legarth, a PhD candidate at University of British Columbia’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, told The Pique news magazine this week.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.