Economists warn of coming stagflation

2021.09.10

There is an old joke often told about economists: Three economists are hunting ducks. The first shoots 20 meters ahead of the ducks, the second shoots 20 meters behind the ducks, and the third says, “Great job! We got them!”

Most people think of money as dollars and cents — bills and coins of various denominations that are printed by a mint. The reality is it’s more complicated. Decades ago, the invention of debit cards transformed physical money into digital currency. Remember walking into a bank and filling out a withdrawal or deposit slip? ATMs did away with bank tellers and the cash economy. In retail banking, balances are credited and debited with the click of a mouse, your bricks and mortar bank replaced by a banking app on your phone.

Increasing the money supply no longer involves a printing press, but rather, adding a collection of ones and zeros on a computer screen. Whereas physical money used to be backed by gold and silver, modern economies are based on fiat (paper) currencies, un-tethered to physical metals. The elimination of the gold standard in 1971 meant that citizens had to put their faith in governments, to guarantee that the value of their money was as printed (bills) or embossed (coins), that a dollar bill was indeed worth 100 cents.

(The failure of fiat currencies to maintain their value is a subject we have covered in previous articles. While the gold price in US dollars has increased over 50-fold, from $35 in 1970 to $1,800 today, inflation has eaten away the dollar’s purchasing power by 90% since 1950. In other words, a dollar worth 100 cents in 1950 is today worth just 10 cents.)

Economic history is rife with examples of countries whose citizens lost confidence in their currencies, usually preceding an economic collapse. Three of the most well known are hyperinflation in Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe, and the 2001 bank run in Argentina.

Losing trust

With this historical context in mind, it is worth gauging the level of trust that Americans hold in the US dollar, and their government more generally.

The results from a recent New Yorker article that did exactly that, are less than sanguine.

Starting with the statement, The dominant tenor of contemporary American politics would seem to be mistrust, the article finds that Democracy’s most basic currency is trust, and, to judge by the usual indicators, we seem to be running out of it. Back in 1964, more than three-quarters of Americans said that they trusted the federal government; today, according to the Pew Research Center, only a quarter of Americans do.

If only 25% of US citizens trust the government, the dollar is also on shaky ground. As the article reminds us, since coming off the gold standard in 1971, the thing you’re trusting is the full faith and credit of the United States government. Fractional-reserve banking, which allows a bank to lend far more in credit than it has in deposits, has driven capitalism for centuries. Many economic crises, when examined closely, turn out to be crises of confidence. This is obviously true of a bank run, when depositors lose faith in the fractional-reserve system, but it’s also true of hyperinflationary spirals, when worries about a country’s handling of monetary policy yank down the value of its currency. There is a reason that the core language of commerce—of bonds and credits—is all about belief.

In this way trust, or the lack thereof, is similar to religion — it’s all about faith. In response to state-sponsored atheism in the USSR during the Cold War, the 84th Congress of 1956 passed a joint resolution declaring “In God we Trust” the national motto of the United States. From that point forward, these words have appeared on all forms of US currency.

Stagflation looms

Stagflation is what happens when rising inflation occurs amid a recession.

The US Federal Reserve’s official line is that inflation is only temporary, however we see things differently.

In June the US consumer price index (CPI) surged by 5.4%, the most since 2008, as economic activity picked up but was constrained in some sectors by supply bottlenecks.

The pandemic has put tremendous pressure on supply chains, and the prices of many agricultural commodities such as grain, corn and soybeans, have skyrocketed. Several industrial metals have enjoyed significant price gains, too, including copper, zinc and lead.

This is due to a number of reasons including demand from China, the world’s largest consumer of commodities whose economy grew at a blistering 18% in the first quarter and 7.9% in Q2.

Supply constraints in certain industries plus greater demand for goods and services is a recipe for higher inflation. To the question of whether inflation is temporary, we are seeing increasing evidence it is not, ie., that rising prices are becoming a permanent fixture of the economy.

The term “recession” is jarring because to most observers, the US economy has been doing well, growing at around 6.5% as virus-related restrictions are lifted amid a relatively successful vaccination campaign of around 60% fully inoculated.

However, recent numbers suggest there is no “V-shaped recovery” and that the economy is slowing. As the Wall Street Journal reports, elevated covid-19 cases and hospitalizations especially the highly contagious delta variant, has the nation “tapping the brakes” in September, with businesses and consumers having to adjust to renewed mask mandates, travel restrictions and event cancelations.

The pace of hiring plummeted in August, with employers adding just 235,000 jobs, compared to about a million in each of June and July. The Department of Labor was expecting 720,000. New restrictions saw restaurants and stores cut staff.

The Mises Institute chimed in with more depressing stats. Mises Wire reported consumer confidence fell to its lowest level since 2011 in July, with the Atlanta Fed reducing its Q3 forecast from 6% growth to 3.7%. Total nonfarm employment is 5.3 million jobs below February 2020’s peak and labor force participation — the number employed or actively seeking employment divided by the working-age population — is well down from 2019 in the 25-54 age bracket.

The article notes the numbers should be much better, given the economy is still receiving so much government stimulus, with federal spending into the trillions, the fact that the government can borrow at rock-bottom interest rates, and because quantitative easing at the pandemic rate of $120 billion in asset purchases per month continues apace.

Moreover, some commentators are uttering terms no one wants to hear or read about, including Desmond Lachman who wrote in The Hill:

Today, with inflation rising to levels last seen 30 years ago and with unemployment remaining stubbornly high amid the COVID-19 pandemic despite massive policy stimulus, we may again be entering a prolonged period of stagflation …

Historian Niall Ferguson concurs, resurrecting memories of the low-growth, hyper-inflationary 1970s, when wages and prices grew by double digits. Ferguson told CNBC that “inflation could be repeating the trajectory of the late 1960s, which laid the foundation for sustained high prices the following decade.”

Harvard economics professor Ken Rogoff, writing for Project Syndicate, suggests the parallels between the 2020s and the 1970s just keep growing. Has a sustained period of high inflation just become much more likely? Until recently, I would have said the odds were clearly against it. Now, I am not so sure, especially looking ahead a few years.

Rogoff points to a couple of key similarities between the economic situation 50 years ago and the one currently:

- Supply shocks. In 1973 OPEC cut off the supply of oil, resulting in massive hikes to the international price of crude. Today, protectionism and a retreat from global supply chains are an equally negative supply shock.

- Government spending sprees. President Lyndon Johnson splashed out big-time during his “Great Society” programs of the 1960s, followed by spending to meet the soaring costs of the Vietnam War. The Trump administration was equally magnanimous, doling out around $4 trillion in pandemic relief, as is the Biden administration whose philosophy of “Modern Monetary Theory” has little regard for fiscal deficits.

Another renowned economist, Nouriel Roubini, believes the stagflation threat is real, having warned for months that the current mix of persistently loose monetary, credit, and fiscal policies will excessively stimulate aggregate demand and lead to inflationary overheating. Compounding the problem, medium-term negative supply shocks will reduce potential growth and increase production costs. Combined, these demand and supply dynamics could lead to 1970s-style stagflation (rising inflation amid a recession) and eventually even to a severe debt crisis.

Roubini identifies nine supply shocks that are likely to keep the prices of goods and services elevated for some time:

- The trend toward deglobalization and rising protectionism

- The balkanization and reshoring of far-flung supply chains,

- the demographic aging of advanced economies and key emerging markets.

- Tighter immigration restrictions are hampering migration from the poorer Global South to the richer North.

- The Sino-American cold war is just beginning, threatening to fragment the global economy.

- Climate change is already disrupting agriculture and causing spikes in food prices.

- Persistent pandemics will inevitably lead to more national self-reliance and export controls for key goods and materials.

- Cyber-warfare is increasingly disrupting production, yet remains very costly to control.

- And finally, the political backlash against income and wealth inequality is driving fiscal and regulatory authorities to implement policies strengthening the power of workers and labor unions, setting the stage for accelerated wage growth.

Roubini writes:

While these persistent negative supply shocks threaten to reduce potential growth, the continuation of loose monetary and fiscal policies could trigger a de-anchoring of inflation expectations. The resulting wage-price spiral would then usher in a medium-term stagflationary environment worse than the 1970s – when the debt-to-GDP ratios were lower than they are now. That is why the risk of a stagflationary debt crisis will continue to loom over the medium term.

Stephen Roach, formerly an economics prof at Yale, and a previous chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, summons the ghost of Arthur Burns, the Fed chair during the Nixon administration, in explaining how inflation is actually worse than reported.

In the 1970s, Burns argued that, since a quadrupling of US oil prices had nothing to do with monetary policy, the Fed should exclude oil and energy-related products such as home heating and electricity from the consumer price index (CPI). Burns also dismissed surging food prices in 1972 as an El Nino weather event, before ordering that food prices need also be stripped from the consumer price index.

What we are left with is the “core inflation rate” supposedly free of “volatile” food and energy. Trouble is, after so much tinkering with the CPI, inflation statistics are misleading, and often end up being minimized. Roach explains:

By the time Burns was done, only about 35% of the CPI was left – and it was rising at a double-digit rate! Only at that point, in 1975, did Burns concede – far too late – that the United States had an inflation problem. The painful lesson: ignore so-called transitory factors at great peril.

Fast-forward to today. Evoking an eerie sense of déjà vu, the Fed is insisting that recent increases in the prices of food, construction materials, used cars, personal health products, gasoline, car rentals, and appliances reflect transitory factors that will quickly fade with post-pandemic normalization. Scattered labor shortages and surging home prices are supposedly also transitory. Sound familiar?

Mises Institute senior editor Ryan McMaken, author of the above-mentioned article, believes stagflation could be avoided through major economic growth and big productivity gains, but that’s unlikely because productivity has already been crippled by American governments’ lockdowns and covid stimulus policies in 2020. Logistics and supply chains are in disarray. The workforce is still down 5.3 million workers from its peak eighteen months ago.

Unless something changes soon, this all points toward a scenario of stagflation.

The 1,000-pound debt gorilla

A period of high inflation and low economic growth is clearly against America’s interests, and the rest of the world’s. However at AOTH, we happen to believe that the more serious threat to the financial system, one that is slowly collapsing under its own weight like a poorly built foundation, is global debt.

Earlier this year, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) found that governments, companies and households borrowed $24 trillion last year to offset the pandemic’s economic toll, bringing total global debt to an all-time high, at the end of 2020, of $281 trillion.

It more than doubled from US$116 trillion in 2007 to $244 trillion in 2019.

The IIF estimates that governments with large budget deficits are expected to add another $10 trillion in 2021.

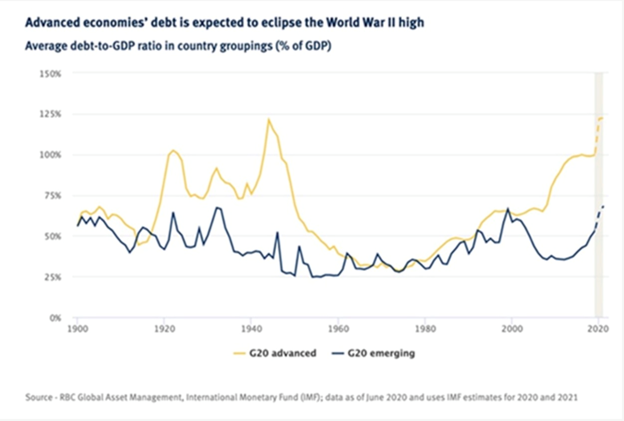

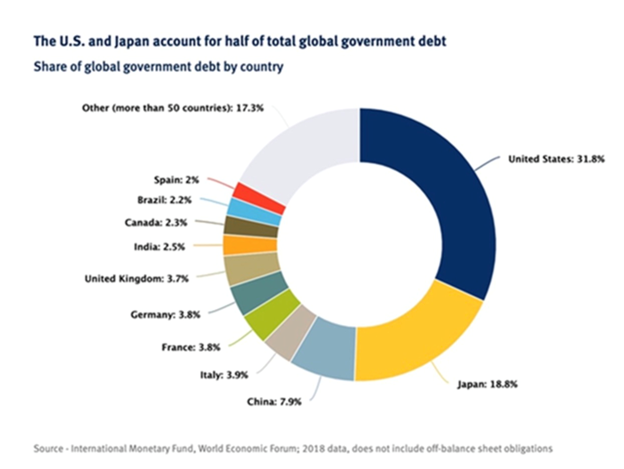

According to the IMF, the public debt of advanced economies has climbed nearly 27% since January 2020, and now sits beyond the greater than 120% of GDP reached after World War II. The United States and Japan are the two most indebted economies accounting for half of total global government debt (see the pie chart below).

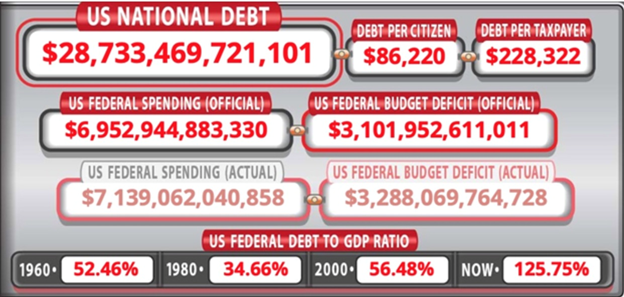

According to usdebtclock.org, the current national debt sits at $28.7 trillion, and it is increasing with each tick of the clock.

The next round of government spending involves President Joe Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure bill, just passed by the Senate but not yet approved by the House; and a $3.5 trillion anti-poverty and climate plan Senate Democrats hope to get passed this fall.

Debt is a major limitation on a growing economy.

According to the World Bank, if the debt to GDP ratio exceeds 77% for an extended period of time, every percentage point of debt above this level costs a country 0.017 percentage points in economic growth. The US is currently at 125.7%, so that is 48.7 basis points multiplied by 0.017 = 0.82, nearly a full percentage point of economic growth!

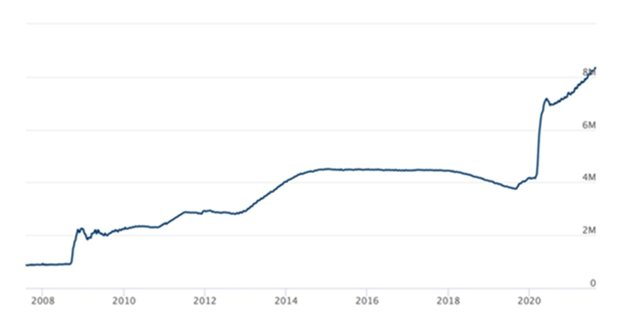

The Fed is severely constrained in how much it can raise interest rates, to quell rising inflation, due to ballooning debt. Following $4.5 trillion spent on pandemic relief, and trillions more to come, through Biden administration spending, along with the continuation of quantitative easing (what I like to call “quantifornication”) to the tune of $120 billion in asset purchases per month, the Fed has in one year doubled its balance sheet to around $8.3 trillion.

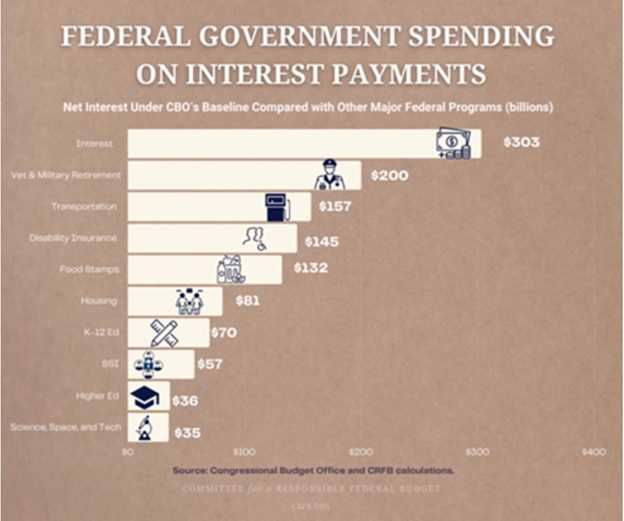

According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the federal government this year will spend $300 billion on interest on the national debt. This is the equivalent of 9% of all federal revenues collected or more than $2,400 per household.

At today’s debt levels, each 1% rise in the interest rate would increase interest expenditures by roughly $225 billion. On a per-household basis, a 1% interest rate hike would increase interest costs by $1,805, to $4,210.

The Fed used quantitative easing in the wake of the 2008-09 financial crisis and it did so again in 2020 to deal with the coronavirus pandemic. (QE continues although the Fed has stated it wants to start “tapering” its monthly asset purchases) QE was successful in preventing a financial meltdown during 2008 and 2020, but the effect has been a reliance on cheap credit that has fueled both a stock market bubble and a real estate bubble that many observers believe is in danger of popping. Bond investors have also become addicted to Fed stimulus.

Excessive money-printing not only in the United States, but Britain and the EU, is continuing to devalue currencies at an alarming rate (this, by definition, is inflation, because it takes more units of currency to buy the same amount of goods as before) — for which precious metals, namely gold and silver, are the best defence.

Conclusion

There was a time when comparing the United States to Italy, whose political culture involves multiple parties holding power in fragile coalition governments, would be a joke. The indomitable power of the US president dwarfs that of the Italian prime minister. The president can and does veto laws, and may issue executive orders without Congress, whereas the Italian prime minister must govern by consensus. The strength of the US economy is symbolized by the dollar, the world’s reserve currency and the most coveted safe haven asset, besides gold, during times of crisis. Financially stable, a beacon of free markets, and up to recently, fiscally responsible, by contrast Italy has been caught in an endless cycle of economic stagnation and debt.

A tax on work forces employers to pay out twice what an employee takes home, Italy’s pension system pays defined benefits pension to people who retire at 40, and there is a 75% tax on gasoline.

Financial analyst Edoardo Cicchella, writing for Mises Institute, argues the United States started down the same road as Italy, what he describes as a growing “Europization”, in 2015:

[T]he Obama administration had just managed to introduce extremely costly and inefficient expansion of Medicare and Social Security, bailed out morally and financially bankrupt Wall Street banks with public money and fueled income inequality with multiple rounds of QE.

Back then, the US debt to GDP ratio was around 70% of GDP, compared to 120% for “financially ruined Italy”. Today, debt to GDP in the United States sits at 125%, with the national debt approaching $29 trillion. (Italy’s ratio is currently 155%). Cichella continues:

Fast forward to the present, a deadly combination of a pandemic and the most leftist U.S. government in history have created long term economic imbalances that will and can not be solved in a couple of years (despite assurance of the “temporary” nature of the interventions by the Government and the Fed). The extremely high level of public spending and government benefits (entitlements) will create huge pockets of the population completely dependent on government support for survival. This can already be observed from the recent difficulty of filling a lot of job vacancies in the U.S. at entry level positions. Why would anybody get a job anyway? People can now make the equivalent of a $25/hr salary by staying at home. (More than that if one is also “informally” employed on the side). In most states you can now make even more than twice your former salary if you were making $10.

It is as if the law of demand and supply does not exist. For sure It does not look like it exists in Washington State, where the breakeven for making more on unemployment benefits is now at $30 an hour, or about $62,000 per year.

In the United States, trust in the government is at an all-time low, a sentiment that played out during the Trump presidency, and the persistent anti-vax movement that has crossed over into Biden’s. Trusting US money means putting your faith in the United States government, the only thing backing the dollar in the absence of a gold standard, and fractional-reserve banking, which allows a bank to lend far more than it has in deposits.

The above-cited economists are right to point out the threat of stagflation in the US economy, where supply shocks are bidding up the prices of good and services, just like the 1973 OPEC oil crisis, and where money-printing “out the wazoo” combined with trillions more in federal spending being pursued by the Democratic left, keeps adding to the sky-high national debt.

The Fed is severely constrained in how much it can raise interest rates, to quell rising inflation, due to ballooning debt. At today’s debt levels, each 1% rise in the interest rate would increase interest expenditures by roughly $225 billion.

The people supposedly represented by the government can’t afford that level of interest (they will suffer higher interest payments on their own debt), same as businesses cannot afford higher interest payments on their loans. Corporations will simply pass on the higher interest obligations to their customers, cut dividends or in the worst cases, lay off staff.

The global debt overhang which has more than doubled since 2007, has severely curtailed governments’ ability to deal with a major financial crisis such as the coronavirus. Interest rates are already so low, that central banks are limited in how much they can cut (the Fed has already “used up all its bullets” in setting interest rates at 0 to 0.25%).

People are being misled into believing that the US Federal Reserve is going to scale back its $120 billion per month asset purchase program (QE) and raise interest rates. The Fed can telegraph its intentions all it wants, the fact remains that at such unsustainably high debt levels, the interest payments will eventually cripple the federal government.

The only way to avoid this impending disaster is a global debt reset — a Debt Jubilee, if you will. Imagine what could be achieved if all the central banks acted together in retiring all the world’s debt — all $281 trillion of government, corporate and consumer loans. Of course the financial institutions would balk; their hand would need forcing. But the effects on the economy would be immediate and profound.

The benefits of a Debt Jubilee would accrue to governments of all stripes, no longer bound to austerity programs; businesses that could invest in their operations instead of paying interest and principal to corporate bondholders; and taxpayers, who would benefit from increased social spending and higher household disposable income.

Because we live in a fiat monetary system, currencies are not backed by anything physical; the reserve currency, the US dollar, was de-coupled from the gold standard in the early 1970s. It’s not like a raid on vaults full of gold, which have an inherent, physical store of value.

In reality there is nothing preventing central bankers from doing a complete global reset, putting all debt back to zero.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.