Nanoplastics — invisible vectors of disease and death

2021.11.25

For years it has been known that plastic breaks down into tiny particles that are consumed by shellfish, fish and mammals higher up the food chain, presenting a danger to human health if consumed.

Our plastic world

It is estimated there are over 150 million tonnes of plastic in the ocean. Around 8 million tonnes enter the seas every year — the equivalent of dumping a truckload of plastic garbage every minute.

On land, plastic pollution has been with us since the material was invented in 1907.

A recent problem has emerged with rich countries shipping their recycled plastic to poorer nations like Malaysia and Indonesia, after China banned imports of recyclable waste. There, piles of plastic garbage are dumped, usually with no market for the stuff, or it is burnt, producing noxious fumes that are breathed by local populations including children.

Since the 1970s North Americans have been taught that most plastic is recyclable. The circular arrows symbol was invented by the plastics industry to indicate a product’s recyclability, however the secret they didn’t want us to know about, was that few plastics are actually recycled; the rest, such as mixed plastics (eg. food wrappers, packaging) are often landfilled or incinerated because it isn’t economical to recycle them.

Only 6.5% of all plastic ever produced since 1950 has been recycled, and many plastics are re-used only once before ending up as waste.

According to a recent report by Statista, the growth of plastic production is three to four times higher than annual population growth, leading to concern about the Earth’s plastic carrying capacity. In 2018, global plastic production amounted to 359 million tonnes, compared to a global population of 7.8 billion, which works out to 47 kg of plastic per person.

As of 2015, the most recent year data was available, plastic consumption was highest in South Korea and Canada, both at 98 kg per capita. Africans consume far less, at just 5.5 kg.

The expected decline in oil production due to vehicle electrification and the switch to renewables, is unlikely to affect plastics, which are a by-product of crude oil. According to the Statista report, Plastics production is forecast to become the largest driver of oil demand growth in the coming years, exceeding the oil demanded by global road transportation by 2050. On a small scale, a one-liter plastic bottle takes 250 milliliters of oil feedstock to be produced.

The trash that never dies

National Geographic says the problem of discarded plastic is so severe, that if nothing is done, by 2050 the oceans will contain more plastic than fish, ton for ton.

It has become a much-discussed topic, and the subject of several documentaries, revolving around the harmful effects of minute plastic fragments, called microplastics and nanoplastics (more on that below), on plants, fish, sea birds, mammals, and eventually, humans at the top of the food chain.

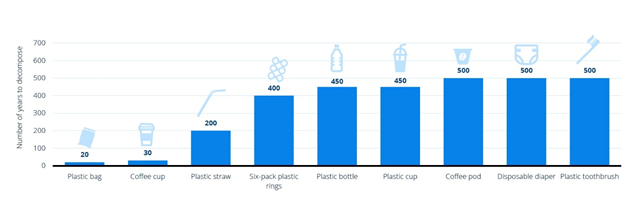

The problem stems from the fact that plastic is virtually indestructible. A trait that was once sold to consumers as a virtue, has become a vice, due to the ubiquity of plastic especially in the marine environment.

Most plastic has a very long lifespan. Plastic bags, for example, can take up to 20 years to decompose, while takeaway coffee cups, despite being mostly paper, have a plastic lining that will endure for 30 years.

Other items, including coffee pods, disposable diapers, and plastic toothbrushes, will be in landfills for five centuries!

Plastic that enters the ocean gets exposed to UV radiation, oxygen, high temperatures and microbial activity. Some plastics, those made from bacterial polymers, are naturally biodegradable. Others, such as take-away food containers, will only decompose when exposed to prolonged temperatures above 50 degrees C, conditions found in an industrial composter that cannot be replicated in the oceans.

Eventually the salt water, sun, wind and waves break the plastics down to tiny particles that are carried by ocean currents to even the most remote corners of the Earth.

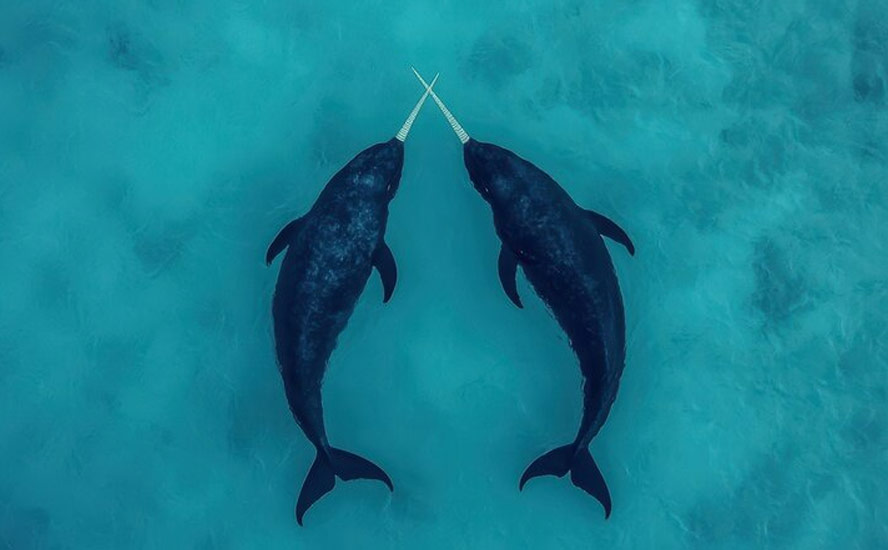

Some marine animals get entangled in plastic fishing nets or are impaled by plastic straws. Others mistake the colorful plastic fragments for food and eat them. However since they cannot be digested, the pieces create a feeling of artificial satiation in the animals that can lead to starvation.

Humans are ingesting plastics as well. According to Statista, every week people consume an amount of plastic the size of a credit card.

Chemical composition

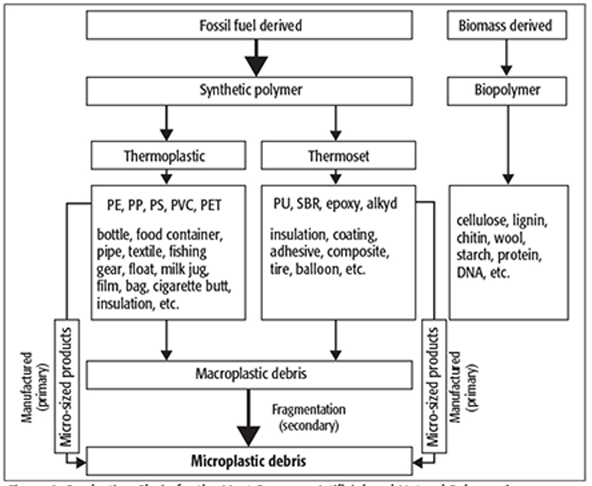

What makes plastic so problematic? The answer comes down to chemistry. Plastic is a polymer molecule consisting of repeating identical units (homopolymer) or different sub-units in sequences (copolymer). Plastics are further categorized as thermoplastics, which soften when heated and can be molded; or thermosets, which cannot be molded or heated.

Both types cause pollution in a marine environment.

Plastics also contain chemicals to improve their properties, that cause harm when they enter the food chain.

Although hundreds of thousands of plastic materials have been invented, only six are extensively used: polyethylene terephthalate (PETE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC-U), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS), or styrofoam.

In the ocean, despite weathering that reduces plastics like water bottles and shopping bags to tiny particles, the original plastic polymer remains intact, unless it is converted into carbon dioxide, water, methane, hydrogen, ammonia and other inorganic compounds — a process that doesn’t happen in a marine environment.

Microplastics and nanoplastics

Especially worrying are “nanoplastics” — pieces that are so tiny, they are able to penetrate human cell walls.

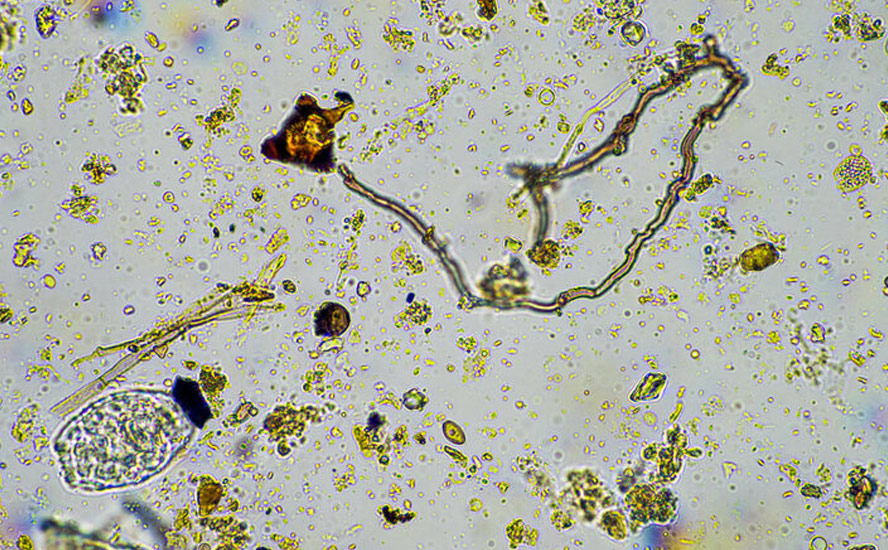

A distinction must be made between microplastics and nanoplastics. The former are plastic fragments up to 5 millimeters, whereas the latter are between 0.001 and 0.1 micrometers (μm). Nanoplastics are so small, they are invisible to the naked eye or even under a simple microscope.

One of the surprising facts about microplastics is how entrenched they are in the global ecosystem. They have been detected in lakes and seas, in the sediments of rivers and deltas, and in the stomachs of the smallest and largest organisms, from zooplankton to whales. One study found that every square kilometer of the world’s oceans has 63,320 plastic particles floating on the surface.

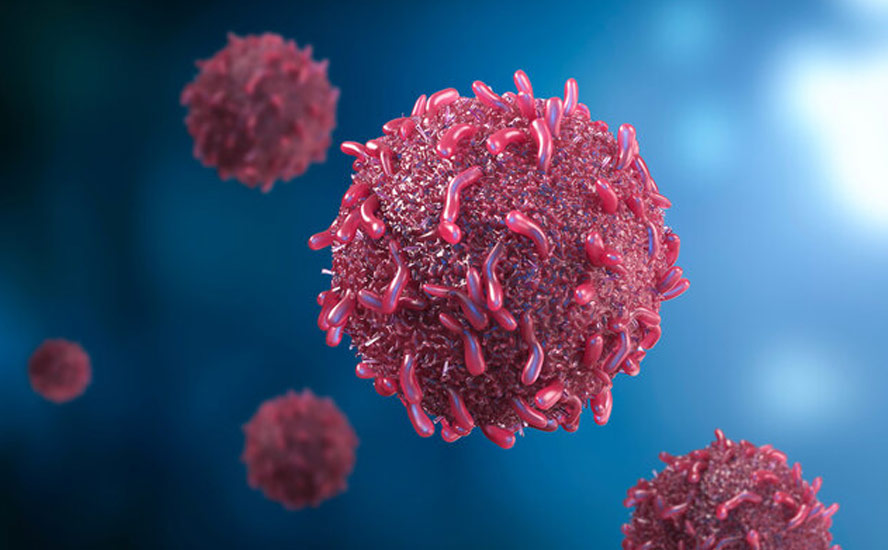

According to Food Safety magazine, microplastics are present in various food products, including seafood, as well as in bottled water. In addition, microplastics can also help introduce other contaminants to foods. Persistent organic pollutants and other toxins in water can also be attracted to these particles. Once consumed by plankton, these contaminants are passed through the food chain to small fish and eventually to humans. While their impact on human health is currently debated, high volumes of microplastics in rats have been found to cause cancer.

Pollution sources

There are a number of ways that plastics get into the environment. Microbeads used as exfoliants in beauty products escape water filtration systems. Other primary sources include plastic powders in molding, and plastic nanoparticles in a variety of industrial processes.

The extensive and indiscriminate use of food packaging, car tires, paints, personal care products (eg. toothpaste) and electronic equipment, are some more contributors to microplastic contamination.

Public awareness campaigns have mostly stopped the use of microbeads, but similar particles continue to be introduced into water systems.

One of the more surprising sources of microplastic pollution is fibers from synthetic fabrics. Plastic fibers from clothing, including polyester, acrylic and polyamides, are shed from garments when they are agitated in washing machines, then drained with the effluent water. Experiments showed up to 1,900 microplastic fibers are released from just one synthetic garment in one wash.

Another less obvious source is the plastic debris from the mechanical abrasion of car tires on pavement. These tiny shards are carried by rain, snow melt and street cleaning into natural stormwater catch basins and municipal drainage systems.

Microplastics can also become part of the water cycle and delivered back to Earth as rain or snow.

Scientists think that tiny particles shed by anything plastic get incorporated into water droplets when it rains, then wash into lakes, rivers and oceans. When the water evaporates, the particles can end up in groundwater. They are then consumed by animals and people via drinking water and food, or breathed in. Microplastics can also attach to heavy metals or hazardous chemicals such as mercury, and adhere to particles from furniture and carpets containing toxic flame retardants, according to a microplastics researcher quoted by The Guardian.

Plastics in the food chain

If nano-scale plastic has become prevalent in drinking water, oceans, rainwater, and the animals that mistakenly eat them, it’s not a stretch to say that microplastics are probably in our food.

One study looking for synthetic particles in sea turtles found microplastics in the guts of all 102 turtles that were examined. They have also been detected in quantities up to 273 particles per pound of sea salt, 300 fibers per pound of honey, and around 109 fragments per liter of beer.

Mussels and oysters harvested for eating reportedly had 0.36 to 0.47 particles per gram, meaning that shellfish consumers are ingesting up to 11,000 pieces of microplastic per year, according to Healthline.

The presence of microplastics in the marine food chain is well documented. As Food Safety explains,

Zooplankton, the microscopic sea organisms at the bottom of the food chain, is eaten by all kinds of fish. Fish ingest small pieces of plastic due to their continuous uptake of water. Microplastics get into the next level of the food chain when other animals eat fish contaminated with microplastics. Eventually, microplastics move all the way up to the top of the food chain.

There is even a scientific term for this process of animals that have eaten microplastics being eaten by other animals: trophic transfer.

A common way for nanoplastics to move up the food chain, is to be first consumed by algae, that is eaten by water fleas, which in turn become fish food.

The problem is not only the nano/microplastics, but the pollutants they carry with them. When plastics move through the food chain, the attached toxins also move, and accumulate in animal fat and tissue through a process called bio-accumulation. Chemicals added to the plastic during the production process can leach from the plastic into the body of the animal that has eaten them. Read more here

Potential adverse effects, at high enough concentrations, may include immunotoxicological responses, reproductive disruption, anomalous embryonic development, endocrine disruption, and altered gene expression.

A laboratory study found fish that were fed nanoplastics, versus those that weren’t, showed abnormal behavior, such as slower eating and hyperactivity.

Among the marine and freshwater species known to ingest water contaminated with microplastics, are fish, bivalves and crustaceans. An animal can also be exposed to microplastics through its skin, or in the case of fish farms, eat plastic-contaminated fish meal.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, of 25 fish species of commercial significance, including Atlantic cod, 11 were found to contain microplastics.

Health impacts

While microplastics’ effects on human health have not been widely studied, it’s safe to say that inhaling or ingesting them should be avoided. This may be extremely difficult however; one study found plastic fibers in 87% of the human lungs studied.

Chemicals associated with plastics are known to be harmful. The most well-studied is BPA — found in plastic packaging or food storage containers. When BPA leaks into food it can interfere with reproductive hormones in women.

Another chemical, phtalates, is used to make plastic flexible. The presence of phtalates in a petri dish was shown to increase the growth of breast cancer cells.

When microplastics were fed to mice, they accumulated in the liver, kidneys and intestines, stressing these organs. Plastics also increased the level of a molecule that may be toxic to the brain, says Healthline.

In a limited study, Canadian researchers estimated the average person ingests over 74,000 plastic particles a year. Examining just a few food categories including fish, shellfish, sugar, alcohol, honey, bottled versus tap water, plus air, the study authors found the most microplastics in air, bottled water and seafood.

Although their assumptions were based on only 14% of an average American’s daily calorie intake, “if our findings are remotely representative, annual microplastic consumption could exceed several hundred thousand,” Science Alert reported.

It is probable that the effects of microplastics ingestion build up over time. Researchers studying microplastics in seafood found that eating accumulated plastic could damage the immune system and upset a gut’s balance. Science Alert states:

Once microplastics enter the gut, they could release toxic substances causing oxidative stress or even cancer, according to the researchers. Particles small enough could be taken up by cells in the lungs and gut; while larger ones might be absorbed in the digestive tract. What happens from here is anyone’s guess.

Conclusion

Plastics have become so ubiquitous – in un-recycled plastic bags, packaging of all shapes and sizes, single-use straws and utensils, coffee pods, plastic microbeads, etc. – that they have literally become part of us. Only 10% of plastic containers are recycled. The rest ends up in landfills, rivers, lakes and finally, the ocean.

Tiny particles shed from thousands, maybe millions of plastic items are getting into the soil, the water, the air and the food chain.

There is currently no regulatory requirement to increase human food safety against plastic contamination. And although some steps have been taken to protect consumers, such as the Obama-era Microbeads-Free Water Act, which banned microbeads from cosmetics, and commitments by large multinationals like Johnson & Johnson, to ensure their products are plastic-free, it appears little concrete action has been taken.

Considering the ubiquity of plastic, it may be impossible to completely avoid it from entering the human body. However, the authors of one of the above-mentioned studies suggest quitting bottled water first. They found bottled water contained 90 more microplastic particles per liter compared to piped-in water. Those who drank bottled water had a daily intake of 349 particles compared to just 16 particles for tap water.

Cutting down on plastic usage is another step in the right direction. Suggestions include choosing re-usable grocery bags instead of single-use plastic bags, buying in bulk, and avoiding goods wrapped in plastic packaging – which account for about 40% of non-fibrous plastics. Participating in your city’s plastic-container recycling program is a no-brainer.

We are now eating, breathing and drinking plastic. Time will tell what its effects will be, but it can’t be good.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.