Global growth spurt, pent-up demand support higher inflation

2021.03.10

The sell-off in bonds that has been tripping up gold prices may be over, with some investors anticipating the bond market will calm down, as appetite for US government debt revives following the sharp rise in yields.

Between lower US Treasury yields — the 10-year benchmark backed off to 1.53% on Tuesday after hitting 1.59% on Monday, the highest in more than a year — and a slumping US dollar (DXY was in the red at 92.05 at time of writing) spot gold was up $35.50 to $1,1718.40/oz in New York.

“We think a big part of the bond-yield move has played out,” Wall Street Journal quoted a portfolio manager at PineBridge Investments. “At this level of yields, we do expect additional buyers to come in. That tends to stabilize the yield level.”

Other large fund managers agree.

David Tepper, the American billionaire hedge fund manager and owner of the Carolina Panthers NFL team, was on CNBC Monday predicting there won’t be much more of a rise in US government bond yields.

Gold bugs are closely watching what happens with Treasuries. Last year, the gold price hit a record high of $2,034/oz, largely due to the fact that investors were piling into bonds as a safe haven against pandemic-related uncertainty. A descending US dollar and negative real rates (when bond yields minus the inflation rate fall below 0%) were also important antecedents.

Another key factor behind rising gold prices, is the widespread fear of inflation.

Gold is a hedge against inflation, so it is generally bought when inflation goes up, or looks like it will, to guard against currency devaluation. Also, when inflation rises, there is a risk to gold holders that the central bank will raise interest rates to stop the economy from overheating ie., from goods and services prices rising so high they begin to affect macro-economic spending. When this happens, investors often flee gold to get higher yields from bonds and other fixed-income assets.

The coming inflation

The dreaded “i” word is starting to be bandied about freely among financial news sites, and for good reason.

Central bankers have realized that keeping interest rates low and maintaining monthly asset purchases (ie. quantitative easing), have not given the desired economic boost; now they are counting on fiscal policy, ie., government spending, to do the trick. However, the US government does not have the money, so they borrow (print) it, at rock-bottom interest rates.

A $2.26 trillion US deficit is predicted for 2021, not as high as 2020’s $3.3 trillion but more than double 2019’s $984 billion, and that is before the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan that President Biden is poised to enact.

Meanwhile Biden’s economic recovery package, expected to be unveiled this month, has as its centerpiece the biggest infrastructure spending commitments since Roosevelt’s New Deal. It includes roads, bridges, and broadband internet access, with progressive Democrats eyeing much more, ie., an expansion of Obamacare and a public sector jobs program.

When campaigning for president, Biden proposed $2 trillion (Progressives in the Democratic Party are calling for up to US$4T) for economic rebuilding, so we expect the infrastructure bill to contain at least Biden’s US$2T, and probably more.

Then there is his Clean Energy Plan, another $2 trillion program to decarbonize US electricity in 15 years and create a net zero-emissions economy by 2050.

The US government has so far spent a jaw-dropping $4.5 trillion on pandemic-related relief, boosting the national debt to $28 trillion in under a year. In October 2020, the debt zoomed past 100% of GDP, for the first time since the Second World War, but that was just the beginning. Based on monetary programs the Fed is already executing, the money supply will increase by another $2.3 trillion this year.

There is a historically close correlation between gold prices and debt to GDP. The higher the ratio, the better it is for gold.

(Adding the $1.9T covid relief bill to the $4.5T already spent gives $6.4T, plus the $7T the Fed added to its balance sheet leaves roughly $14 trillion, or half the national debt. That is before Green New Deal spending, and promised social program spending by the Democrats, for example billions on health care and education, that remember, could easily be passed due to their majorities in Congress, and we could be looking at another $10-$14 trillion.)

This new spending, which would be unprecedented, is in addition to the loose monetary policy that is being followed by the Fed, meaning continued asset purchases to increase the money supply, and keeping interest rates close to zero. So far, the Fed’s creation of money literally “out of thin air” has added about $7 trillion to its balance sheet since covid-19 hit.

Thus, we have monetary easing happening at the same time as fiscal spending “carte blanche” (remember Biden believes strongly in the power of the state to tax and spend. A long wish list waits to be filled, with little to no concern regarding the already out of control $28 trillion national debt, courtesy of Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT)

The result of these two forces acting together, is bound to create inflation. We did not get inflation during the financial crisis because we did not have the spending component. All the money stayed within the banks. This time is different.

Last month Lawrence Summers, the former treasury secretary for Bill Clinton and economic adviser to Barack Obama, wrote in an op-ed for The Washington Post that Biden’s stimulus might cause “inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation, with consequences for the value of the dollar and financial stability.”

Already, we know that several commodities, from copper to crude oil, have been surging in price. The CRB Commodity Index is up 30% since last August.

Food prices are rising higher than inflation and incomes in many parts of the world, including the United States, where food security has become a serious issue, during the pandemic.

Meanwhile a global manufacturing surge is accelerating goods inflation, while the prices of services, many of which are down because of covid, remain in a slump. US prices of durable goods rose 3.5% in January compared to only a 1.3% increase for services. According to the Institute of Supply Management, via Reuters, last month saw one of the most widespread improvements in business conditions in 30 years, with the composite purchasing managers’ rising to 60.8 in February, the highest level since February 2018 and before that May, 2004.

Consider too: the primary risk to an extraordinary expansion of the money supply is inflation. Just ask the Fed officials who tried, and failed, to control inflation through monetary expansion during the hyperinflationary 1970s. It did not work, with average inflation during that period hitting 13.5% — unheard of by today’s standards.

GDP growth and inflation

Now, aside from all these inflationary factors, that are in the mix, we have another important one to consider, and that is economic growth.

Economic theory posits that typically, higher inflation is caused by strong economic growth. This makes sense, given that, during periods when aggregate demand (the total demand in an economy) outstrips aggregate supply, of goods and services, we are likely to have higher inflation.

Inflation can mean either an increase in the money supply or a rise in price levels. Loose monetary policy such as we see being practised by the US Federal Reserve currently, thus creates a risk for inflation.

How do prices rise? It is fairly simple. An economy operating at near full employment (with healthy GDP growth say in the range of 0 to 5%) is known to cause two things to happen: aggregate demand for goods and services increases faster than their supply, causing prices to rise; and companies raise wages because of a tight labor market. These wage hikes are usually passed onto consumers in the form of higher prices.

Readers will recall that, in 2020, the US Federal Reserve dropped interest rates to near zero, after letting them rise, modestly, for the previous three years. The goal was to get higher inflation. Other central banks did the same.

Now, as economies slowly begin to recover from the pandemic, lockdowns are lifted, and vaccination programs accelerate, there is an opposite concern, of economies overheating.

The concern is well justified.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) this week put out a forecast saying that the global economy will rebound to pre-pandemic levels by the middle of this year, at 5.6% growth. This is much better than predicted only a few months ago. In early December, the Paris-based organization forecast 4.2% growth in 2021 and 3.7% in 2022.

The revised numbers for the United States are particularly impressive. The US economy is expected to grow 6.5% this year, nearly double the OECD’s December forecast of 3.2%. The economy shrank in 2020 by 2.3%, or around half a trillion dollars.

US unemployment is finally starting to improve after several months of high jobless figures. Employers added 379,000 jobs in February, nearly doubling the projection and pushing the unemployment down to a more respectable 6.2%.

The OECD thinks the US’s planned $1.9 trillion stimulus package, including direct payments of $1,400, will add more than one percentage point to global growth, and be a boon to its trading partners, boosting Canada’s and Mexico’s GDP by 0.5% to 1%, and between a quarter and half a percent in the EU and China.

The largest consumer of commodities, and a key driver of metals prices, is expected to grow its economy by a blistering 7.9%. Chinas was the only major economy last year to post a positive economic output figure, having managed to move past the pandemic faster than other countries, despite covid-19 originating in the Chinese city of Wuhan.

However, all this expected growth, thanks partly to US stimulus, comes at a price. Reuters reports the downside is an increase to the inflation rate of 0.7% per year, on average, in the first two years, meaning by the end of 2022, we could see inflation close to 3%! (double the current 1.4%).

Note that this is well beyond the Federal Reserve’s 2% target and would likely call for some kind of policy response, to either reduce the money supply, increase interest rates, or both.

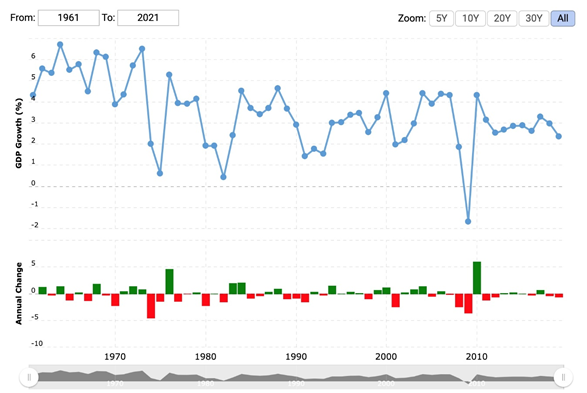

We can actually plot the historical relationship between GDP growth and inflation by taking a look at some of the most expansionary periods in recent US economic history and checking how inflation and GDP were doing.

For example, the United States economy enjoyed a 92-month expansion between December 1982 and July 1990, during which GDP climbed to nearly 5%. The Federal Reserve managed to tame double-digit inflation by tightening monetary policy, resulting in inflation falling to 6% in the late 1980s, but by 1990, prices had crept back up to 8%, in line with higher GDP growth.

Following a mild recession in the early ‘90s, the US economy was back firing on all cylinders between 1991 and 2001. Here we see GDP growth move from just over 1% in the early ‘90s, to 4.5% in 2000, which corresponds to the “dot-com bubble”. Inflation in the 1990s goes as high as 10% in 1994, before falling back to about 3% in 1999. Admittedly the correlation to GDP does not seem to be as high as during the previous decade.

It is also interesting to see how the two variables line up during the financial crisis of 2008-09. In the run-up to the crisis, US GDP grows at a rate of around 4.8% during the mid-90s, before crashing to almost -2% in 2009. Inflation during this period is practically a mirror image, with prices rising as high as 8.5% in 2008 (remember WTI crude oil hit an all-time high of $167.30 in June 2008), before plummeting to just over 2% in 2009.

One more thought before leaving the topic of GDP growth and inflation. The growth projections are only good this year because last year’s figures were so bad.

Check out these facts, courtesy of The BBC:

- The FTSE dropped 14.3% in 2020, its worst performance since 2008.

- In the United States, the proportion of people out of work hit a yearly total of 8.9%, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), signalling an end to a decade of jobs expansion.

- The IMF estimates that the global economy shrunk by 4.4% in 2020. The organisation described the decline as the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

- Retail footfall has seen unprecedented falls as shoppers stayed at home. The country worst affected was Germany, where there was 97% less footfall, followed by the UK at -78%. In the US, there was only a 20% reduction in shoppers to bricks and mortar stores.

- Accountancy giant EY says 67% customers are now not willing to travel more than 5 kilometres for shopping. This change in shopping behaviour has significantly boosted online retail, with a global revenue of $3.9 trillion in 2020.

The $2.9T burning a hole in your pocket

The narrative of higher bond yields, driven up because bond holders are selling to take profits and getting into more risky assets like stocks, which are looking decidedly bubbly, and robust global growth, on account of trillions in covid stimulus and economic recovery funding yet to be doled out, also has a subtext of pent-up consumer demand.

What happens when millions of people whose spending has been forced online, get inoculated and start shopping again? The result is almost certain to be inflationary.

Consider:

According to estimates by Bloomberg Economics, consumers in the world’s largest economies amassed $2.9 trillion in extra savings during covid-related lockdowns — with half of that total, $1.5 trillion, in the US alone. Bloomberg notes the $2.9T is at least double the average annual growth of gross domestic product seen during the last expansion, and equivalent to the annual output of South Korea.

Americans are reportedly squirreling away their money like never before, thanks to $1,200 stimulus checks and other covid relief programs. At the end of 2020, US banks held a record $17.8 trillion in deposits, which put pressure on savings account yields. In February, the average interest rate for a personal savings account fell to 0.49%, a new all-time low. But people have to put their money somewhere, and not everyone has the wherewithal to buy and sell stocks.

Americans have never been big savers, though, so for us at AOTH it is a pretty sure bet that, once mask mandates and restrictions on group gatherings and the like are lessened or rescinded, folks are going to spend like drunks on a booze cruise. Continued low interest rates will encourage the opening of wallets and purses to levels likely not seen in decades.

BNN Bloomberg reports that, should all the money saved over the past year in the US be spent, it would propel economic growth as high as 9%.

All that pent-up capital is highly positive for economic growth going forward, but there is also the risk of it fueling inflation. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has already said the Fed plans to let inflation run a little hot to meet a long-term average of 2%. How much higher remains to be seen but there is certainly the potential for it getting out of control.

Conclusion

Higher inflation is good for gold especially if Treasury yields do not get too high, a situation that would give negative real interest rates. Historical charts prove that every time yields fall below the rate of inflation, ie. they turn negative, gold goes up.

Apart from negative real rates, gold is also, we believe, destined for the next leg up once investors realize the US dollar is being massively devalued.

Gold generally moves higher when the dollar drops. Right now, the US dollar index DXY is holding around 90, but what happens when people realize the federal government has depreciated the greenback by spending $6.5 trillion using borrowed money, plus the Fed’s $7 trillion, meaning the purchasing power of the dollar has been cut in half? The equivalent of half the $28-trillion national debt? And with trillions more of debt to come, at AOTH we believe there is only one way for the dollar.

Finally, it was interesting to read Mark Bristow’s comments this week on gold prices. The CEO of Barrick Gold said during the PDAC conference that he believes there is an “over-exuberance” in the financial markets right now, with investors piling into assets that do not have any real value, such as bitcoin.

“We saw this over-exuberance been 2009-10 and then a major crash,” Bristow said, adding that these developments benefited gold and will support the precious metal again.

“We saw a first spike in the gold price; there is another one coming.”

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.