Why copper supply is the biggest roadblock to a clean energy future

2020.07.25

Nothing glitters like gold but it’s copper that literally makes the world go round.

The Copper Development Association divides copper usage into four categories: electrical, construction, transport and other. By far the largest sector is electrical, at 65%, followed by construction at 25%.

Copper is useful for electrical applications because it is an excellent conductor of electricity. That, combined with its corrosion resistance, ductility, malleability, and ability to work in a range of electrical networks, makes it ideal for wiring. Among electrical devices that use copper, are computers, televisions, circuit boards, semiconductors, microwaves and fire prevention sprinkler systems.

In telecommunications, copper is used in wiring for local area networks (LAN), modems and routers. The construction industry would not exist without copper; it is essential for wiring in residential and commercial construction. The red metal is also used for potable water and heating systems due to its ability to resist the growth of water-borne organisms, as well as its resistance to heat corrosion.

The transportation industry relies on copper for core components of airplanes, trains, cars, trucks and boats. A commercial airliner has up to 190 kilometers of copper wiring, while high-speed trains use up to 10 tonnes of copper per kilometer of track.

Automobiles have used copper and brass radiators and oil coolers since the 1970s. More recent applications including on-board navigation, anti-lock braking systems, heated seats, defrosting wires embedded in windows, hydraulic lines, and wiring for window and mirror controls.

In electric vehicles (EVs), copper is a major component used in the electric motor, batteries, inverters, wiring and in charging stations.

An average electric vehicle contains 85 kilograms of copper compared to 25 kg for regular vehicles. The EV “revolution” includes not only cars, but trucks, trains, delivery vans, construction equipment and two-wheeled vehicles like e-bikes and scooters.

The latest use for copper is in renewable energy technologies, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines.The base metal is also a key component of the global 5G buildout.

Even though 5G is wireless, its deployment involves a lot more fiber and copper cable to connect equipment.

The ubiquity, and importance of copper has earned it a nickname. “Dr. Copper” seemingly has a PhD in economics for its ability to predict future industrial demand, and countries’ economic growth rates, expressed as gross domestic product (GDP).

Lately copper prices have rallied on a combination of robust demand from China, as the economy of the world’s largest copper consumer emerges from the pandemic needing more of the red metal; and supply disruptions in South America, where the majority of the world’s copper is mined.

If fact, many copper watchers were expecting the essential industrial metal to take a big hit from the coronavirus, but if current market fundamentals persist, we might even see copper posting a 2020 gain on economic recovery momentum.

The forecast calls for pain

In 2018, before the trade war between the US and China put the boots to copper demand, and covid-19 mine closures/ abandoned expansion plans crimped supply, we made a bold prediction: that copper supply is NOT going to be able to keep up with demand in the long-term. Here’s what we wrote, in The coming copper crunch:

Even with expansions at existing mines and the ramp-up of the relatively few new copper mines like Cobre Panama, Radomiro Tomic and Toquepalain, it will not be enough to meet the onslaught of demand that is coming from China as it continues to modernize and urbanize, and electric vehicles, which use three times as much copper as regular ones. In 2016 Chinese automakers sold 28 million cars. If China follows through on its promise to go 100% electric, that would mean 2,380,000,000 kilograms of copper. At the current production rate of 20 million tonnes a year, that’s 119 years worth of copper! Just to produce enough copper for electric cars in China.

Do we expect 100% EV penetration? No. But the shift to electrification of our transportation system is real, it’s not going to go away or stop. Because it’s as real as the shift from wood to coal to fossil fuels and now to lithium. That means massive new copper supplies are needed just for Chinese EVs, whatever the EV penetration eventually turns out to be. And remember there’s the rest of the world to supply for EVs, charging infrastructure, and all of copper’s other uses.

Bottom line? We gotta find more copper.

To understand how we came to this conclusion, let’s back up a bit.

In 2018, global accounting firm KPMG predicted that by 2020, global copper demand will outstrip mine output and will pull even with refined copper production. By 2020 the consultancy said copper consumption will reach 24.5 million tonnes “driven by growth in global industrial production and higher investment in energy infrastructure.” An acceleration in demand for EVs and renewable energy between 2018 and 2020 were expected to be the main copper demand drivers.

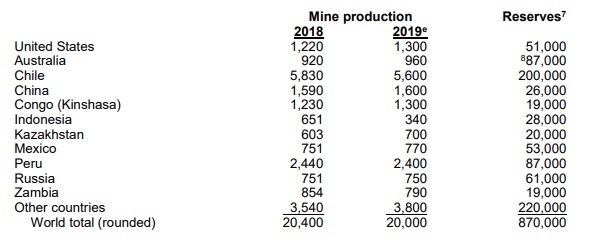

In 2019, all of the copper mined throughout the world amounted to 20 million tonnes.

According to the International Wrought Copper Council, global reported refined copper demand in 2019 was 23.915 million tonnes, leaving a market deficit of roughly 4Mt.

The obvious solution is to just crank out more copper, but this is often a tall order for existing mines.

Because copper is infamous for its unpredictable supply, analysts covering copper build a disruption allowance into their estimates, typically 5% of global mined supply. Disruptions in the copper market, such as strikes and poor weather, averaged 900,000 tonnes of copper supply per year between 2004 and 2012; 2015 saw a record mine disruption of 1.33Mt.

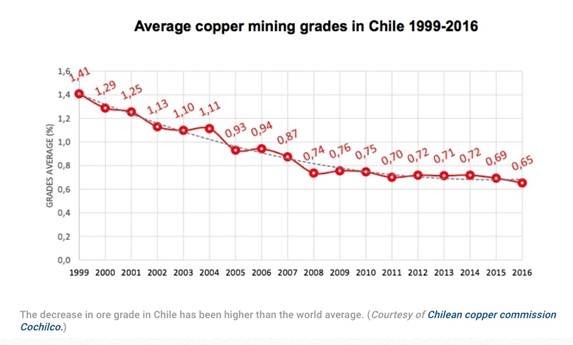

Lower ore grades also must be factored in. Copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile in the last decade – highlighting the urgent need for grassroots exploration to arrest the trend.

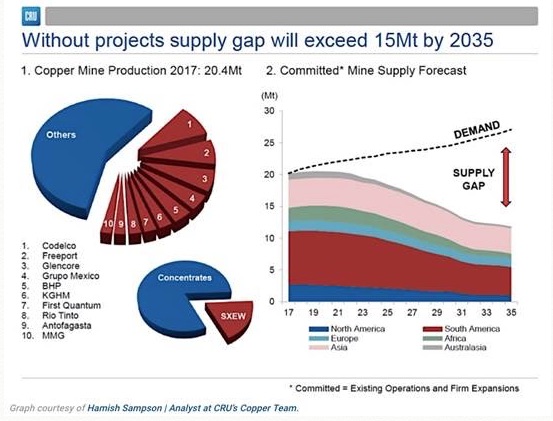

Without new capital investments, Commodities Research Unit (CRU) predicts mine production will drop from the current 20 million tonnes to below 12 million tonnes by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15 million tonnes. (see chart below). That’s because over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

Only if every single copper project currently in development or being studied for feasibility is brought online before then, including most discoveries that have not yet reached the evaluation stage, could the market meet projected demand, according to CRU.

The supply gap requires that every copper mining project with a feasibility study is developed, and over 90% of new projects “see the light of day”.

Problem is, all the low hanging copper fruit has been picked – either mined or recycled – so where are new economic copper deposits to be found? Among the bottlenecks to finding new copper, are the fact that major mining companies slashed exploration budgets during the lean years 2012-16; and that capital costs for building new copper projects are too high.

Our prediction of long-term copper supply not meeting demand, especially the massive red-metal requirements for transportation electrification, has already come true. Supply was already tight before the coronavirus; covid-19 has only made matters worse.

Covid supply restrictions

Earlier this month, hundreds of mine workers in Chile getting sick from covid prompted Codelco, the world’s largest copper mining company, to shutter its Chuquicamata smelter and refinery to prevent the spread of the virus.

Labor unions in Chile are demanding that companies do more to safeguard the health of their workers, particularly at state-owned Codelco, where three miners died from coronavirus.

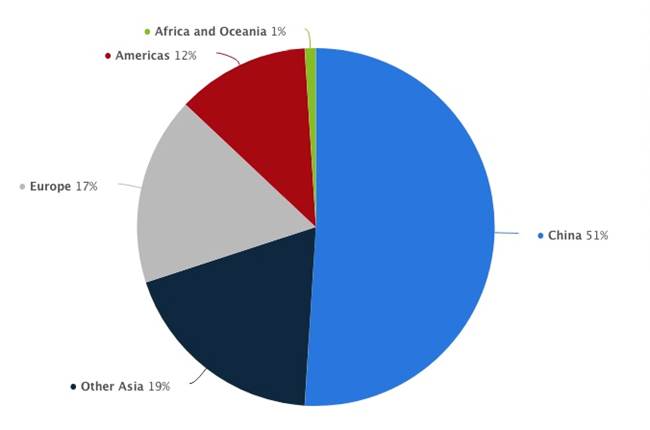

Though temporary, mine closures are ringing alarm bells throughout the copper market and bidding up prices, as investors fret over whether the industry can meet demand, especially now that China, which consumes 51% of the world’s copper, appears to be back on its feet.

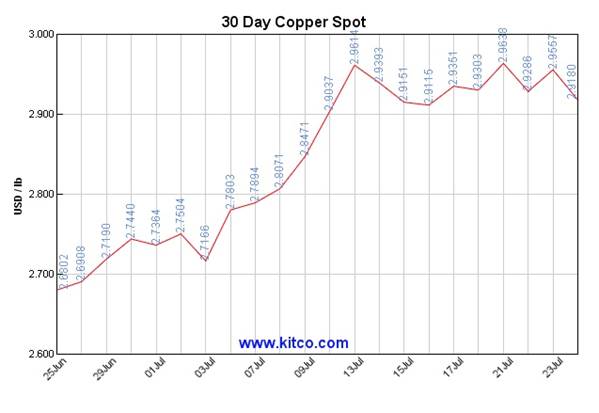

On July 21 copper futures flirted with $3 a pound, hitting a two-year high of $2.97, after an agreement of a large economic stimulus plan in Europe and optimism about a covid-19 vaccine combined with worries about pandemic-hit supply from top producers Chile and Peru.

Imports from China rose 50% from May, with June cargoes double that of the same month last year, as the country’s infrastructure and manufacturing sectors recover from the February-April covid-19 slump.

Meanwhile the copper supply picture in South America continues to darken.

In a recent note, Capital Economics wrote that production has fallen sharply in Chile, Peru and Mexico, which combined account for 45% of copper production. At Escondida, the world’s largest copper mine, output is now at levels last seen in 2017, during a protracted strike.

Along with the Chuquicamata smelter closure, Codelco has largely given up on project development, to focus on running existing mines with reduced staff. It has halted a major expansion project at its Chuquicamata mine, to move operations from open-pit to underground, and put another expansion on ice at El Teniente, its largest and most profitable mine.

According to Bloomberg, Codelco needs to spend more than $40 billion over the next decade just to maintain production:

Codelco’s so-called structural projects are set to contribute more than half of its output by the end of the decade, according to CRU Group. If it doesn’t upgrade assets, it risks an output decline of 600,000 tons, CRU estimates. That’s enough to wire more than 7 million electric cars.

Because the state-owned miner produces so much of the world’s copper, even a relatively small percentage decrease in production has the potential of reducing global supply by around 2%, putting an already under-supplied market further into deficit.

The fact that Codelco is not doing very well, financially, sharpens this concern. Part of the problem is that ore quality at Codelco’s aging deposits is falling, meaning more ore must be processed to produce the same amount of metal, driving up costs. Bloomberg states,

In November, Chief Executive Officer Octavio Araneda slashed Codelco’s project budget through 2028 by $8 billion, placing the future of the Andina, Radomiro Tomic and Salvador expansion projects in the balance…

“It’s not like they’re going to get into severe financial distress, but it just makes it more challenging for them to balance the books in terms of project spending,” said [BMO Capital Markets analyst Colin] Hamilton.

Some of those projects, which were due to be commissioned in the late 2020s to early 2030s, probably will be postponed indefinitely, and could result in a loss of 500,000 tons of copper, said BMO’s Hamilton.

“I do think there’s a risk we’re going to be downgrading the supply forecast over the coming years,” he said.

Codelco isn’t the only mining company facing troubles; some of its private-sector peers are also staring into an open-pitted abyss.

Anglo-Australian diversified miner Rio Tinto recently warned the global copper supply crunch could worsen, owing to covid-19, with its own production of the base metal falling 3% in the second quarter.

Rival BHP lowered its 2020-21 guidance to between 1.48 million and 1.64 million tonnes, down from 1.72Mt produced in the prior year.

And Teck Resources, which expected to finish its Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 expansion in the last quarter of 2021, says the project may be delayed up to six months, due to pandemic-related disruptions – costing the Canadian major miner between $260 million and $290 million.

QB2 is expected to extend the aging deposit by 28 years, significantly boosting production to 300,000 tonnes a year from a mere 23,400t in 2017. A planned Phase 3 would double that to 600,000 tonnes of copper per annum, making the operation Chile’s second largest, after Escondida.

Over in Peru, nation-wide quarantines have had a negative effect on copper mining. Among the affected large-scale operations, are Antamina, Cerro Verde and Las Bambas.

A recent report by S&P Global Market Intelligence found Latin America is the hardest-hit, in terms of the value of at-risk production, out of disruptions to 275 mine sites in 36 countries.

Strikes, that old bug-bear of the copper industry, are also looming in Chile, adding more uncertainty to the covid-fueled mix. Recently Chilean miner Antofagasta and workers at its Zaldivar mine decided to extend government-mediated talks, to avoid a strike. The mine co-owned by Barrick Gold accounts for around 2% of the country’s copper production.

Workers at the company’s Centinela mine, however, on July 13 rejected a final wage offer and voted to down tools.

Lundin Mining’s Candelaria operation reduced its payroll by 7%, to help contain virus spread in the top copper-producing nation, Bloomberg said.

Dwindling inventories

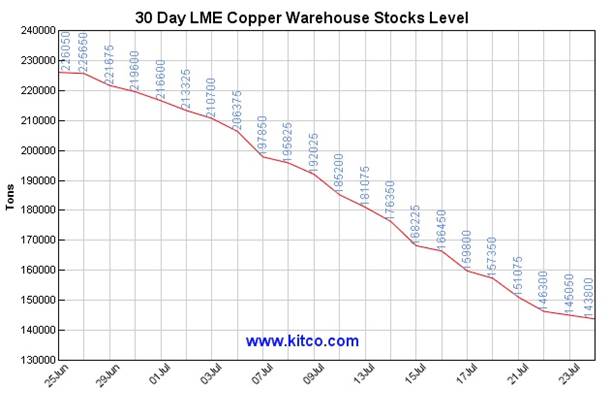

All of these closures and reduced output is taking a toll on the world’s supply of stored copper.

Copper stocks at LME warehouses in June fell below 250,000 tonnes for the first time in seven years. 30-day LME copper warehouse stocks on Friday were down to 143,800t.

Electrification challenge

Copper’s widespread use in construction wiring & piping, and electrical transmission lines, make it a key metal for civil infrastructure renewal.

A report by Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization and electricity demand. Total world mine production in 2019 was only 20Mt.

The continued movement towards electric vehicles – including cars, trucks, trains, delivery vans, e-bikes and scooters, is a huge copper driver.

We already calculated, if China follows through on its promise to go 100% electric, that would mean 2,380,000,000 kilograms of copper. At the current production rate of 20 million tonnes a year, that’s 119 years worth of copper! Just to produce enough copper for electric cars in China.

Before the covid-19 pandemic, we already had the beginnings of a copper shortage. But it wasn’t expected to hit until the early 2020s. The issue was sidelined in 2018-19, due to the China-US trade war, a period in which demand for most industrial metals, including copper, fell.

Now along comes the covid-19 pandemic. Copper supply problems are suddenly back in the spotlight, following a flurry of temporary mine closures that are reducing output in Chile, Peru and Mexico, which account for nearly half (45%) of global production.

China, Europe and the United States have all decided, and we agree with them, that the way forward, to pull their economies out of the growth-killing pandemic, is to create massive infrastructure-spending programs, with a concentration on clean energy and transportation, and reducing carbon emissions.

Beijing recently kicked off a $700 billion program focused on “new infrastructure” and “new urbanization”. Urbanization refers to refurbishing old urban housing stock, railways, airports, and upgrades to power grids and local utilities. Infrastructure includes 5G networks, ultra-high voltage power grids, EV charging stations and data centers.

The European Commission has released a €1.85 trillion recovery plan focusing on “EU Green Deal” initiatives aimed at reaching the eurozone’s net emissions by 2050 target.

The Trump administration is said to be preparing a nearly $1 trillion infrastructure proposal – some of the dollars are geared toward 5G/ broadband.

If elected President, Democrat Joe Biden would end power plant carbon emissions by 2035, and spend $2 trillion over four years on clean energy projects. The former Vice President would also hand out cash vouchers allowing citizens to trade in their gas-powered cars for electric vehicles, and steer tens of billions of dollars toward building charging infrastructure in rural communities.

Biden proposes extending clean energy tax credits and installing millions of solar panels, and wind turbines both onshore and offshore, in an attempt to chip away at the nearly two-thirds of US electricity generation that still comes from fossil fuels.

Grid-scale energy storage, shifting major cities towards public transportation, and upgrading 4 million buildings and weatherizing 2 million homes over four years to increase energy efficiency, are also called for under his plan.

Clearly, a global infrastructure push, or one pursued by the major economies of the EU, the US and China, would mean a lot more metals will need to be mined, including copper for electric vehicle wiring, renewable energy projects and 5G; and silver, used extensively in solar panels and 5G.

How much more copper?

According to BloombergNEF, there are currently about 7 million electric vehicles in the world today. By 2040, they estimate around 30% of the world’s passenger cars will be electric. To me that’s a conservative and reasonable number. It means 500 million EVs will be on the road in 20 years, out of a total vehicle fleet of 1.6 billion. If each EV contains 85 kg of copper, that is 42,500,000,000 kg, or 42,500,000 tonnes of copper, roughly twice the current volume of copper produced by all of the world’s copper mines.

Just so we’re clear – in 20 years, we need to double the amount of global copper production, just to meet the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles. We still need to cover all the copper demanded by electrical, construction, power generation, renewable energy, 5G, etc., plus all the new copper demand from countries that currently can’t afford a Western lifestyle with all its metals-intensive modern products. Where is this new supply going to come from?

Of course, there is also the extra copper and numerous other metals including iron ore, nickel, zinc, etc., that come with a global infrastructure buildout necessary to get global growth moving again after this devastating covid-19 outbreak is brought under control! If we are talking about a green infrastructure buildout, such as Biden’s $2 trillion clean energy plan, it will require even more copper.

Reaching 100% renewables in the United States would mean adding about 200,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines, according to an analysis by Wood Mackenzie. Depending on whether the transmission lines are underground or overhead, this will require millions of pounds of copper and aluminum (underground electrical cables are mostly composed of copper; overhead power lines are generally made of aluminum, though some copper is used in medium-voltage distribution and low-voltage connections to customer premises).

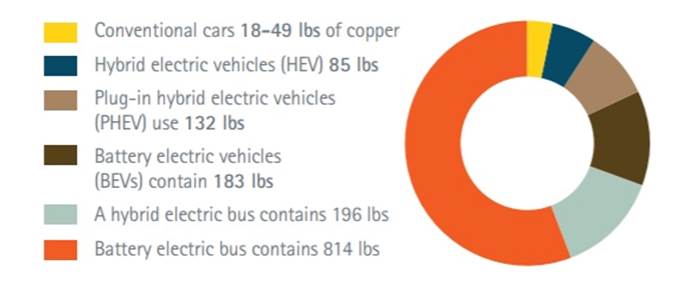

A hybrid electric bus has 196 pounds, and 814 pounds of copper go into a hybrid-electric bus, mostly the battery.

Wood Mackenzie states that US utilities have invested nearly $2.3 billion in EV charging infrastructure. The consultancy predicts that by 2030 there will be more than 20 million (residential) charging points consuming over 250% more copper than in 2019.

With each residential charger using about 2 kg of copper, that’s 42 million tonnes, or double the current amount of copper mined in one year.

One of the largest manufacturers of public charging stations, ChargePoint, is targeting a 50-fold increase in its global network of loading spots by the mid-2020s. A Level 2 charging station requires 7 kg of copper, a DCFC station uses 25 kg.

Conclusion

Unless the mining industry is able is able to ramp up, or more accurately, multiply the amount of global copper produced on an annual basis, countries are going to have to temper their expectations of how quickly, and to what extent they are able to shift from fossil-fueled power and transportation options to renewables and electrics.

The logistics of producing that much copper, to feed so much demand, in so short a time, just 20 years, are daunting. It would not only require existing mines to go exploring and find new metal to feed their operations, but developing brand new, or in industry parlance, greenfield projects that have never before been mined. And that brings us back to our original problem: all the low-hanging copper fruit has been picked – either mined or recycled – so where are new economic copper deposits to be found?

As demand continues to outstrip supply, what do you think will happen to the copper price? Building an EV is already expensive – automakers stomaching higher-priced materials like copper will pass them onto the consumer, thereby keeping EVs out of reach for a large part of the population.

As automakers wait for new copper to be found, and prices to stabilize, they will continue to crank out traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Diesels will soon become a dinosaur of a technology; unable to meet stricter tailpipe emissions standards, they will continue to lose ground to gasoline-sipping cars and trucks.

Hybrids are a natural bridge between a conventional vehicle and an EV – not a bad thing considering that motorists still have a hard time grappling with the “range anxiety” associated with a pure EV, not to mention the logistics of finding a charging station and the high sticker prices.

Both hybrids and gas-powered vehicles require catalytic converters made up of platinum group elements, especially palladium.

More outside-the-box thinking will be required to transition to zero-emissions vehicles.

Canada is a pioneer in hydrogen fuel cells installed in hydrogen cars, buses and vans, led by Ballard Power Systems and Hydrogenics.

Other nations moving towards a green hydrogen economy include Australia, China, France, Germany, Norway, South Korea, the UK and the United States, according to Greentech Media. Hydrogen could potentially even replace diesel as baseload fuel on remote mine sites.

At AOTH we are behind these developments 100%. The existence of climate change, either human-caused, due to natural cycles or both, is no longer up for debate. To avoid ecological catastrophe, we must reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, clean up our environment, embrace renewable energies, and continue down the path of electrifying the global transportation system.

We also need to find more copper.

As smart resource investors, we want to be invested in metals, and companies, that are at the leading edge of a trend. At AOTH we see gold, silver and copper as THE best metals to own right now, considering the multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure programs being promised by the two presidential candidates, as well as the EU and China.

On Friday gold was on its way to breaking 2011’s all-time high, after blowing past $1,900 an ounce. Silver was also on a tear, finishing the weak at $22.77/oz, its best performance since May, 2013.

Owning gold, silver and copper, or better yet, the companies that are exploring for them and offer the best leverage against rising prices, seems to me a very prudent investing strategy going forward.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Facebook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.