Nickel

As it has done with cobalt, graphite and rare earths, China appears to be cornering the battery nickel market.

Reuters reported on a $4 billion Chinese-led project to produce battery-grade nickel chemicals, that Indonesia hopes will attract electric-vehicle makers into the country.

Construction started last year, led by a consortium of Chinese developers including the world’s largest stainless steel maker, Tsingshan Holding Group, battery company GEM Co Ltd., and units of CATL – the largest EV battery company in the world. Nickel feedstock for the plant would come from Indonesia’s nickel laterite ores (Tsingshan says the feed would be abandoned low-grade nickel ores)

The nation of islands wants to become a global hub for processing raw nickel into battery-grade nickel sulfate, and for producing/ exporting EVs to Asia and possibly Australia. Indonesia is the largest nickel producer by far, last year outputting 800,000 tonnes compared to 420,000 from its closest rival, the Philippines.

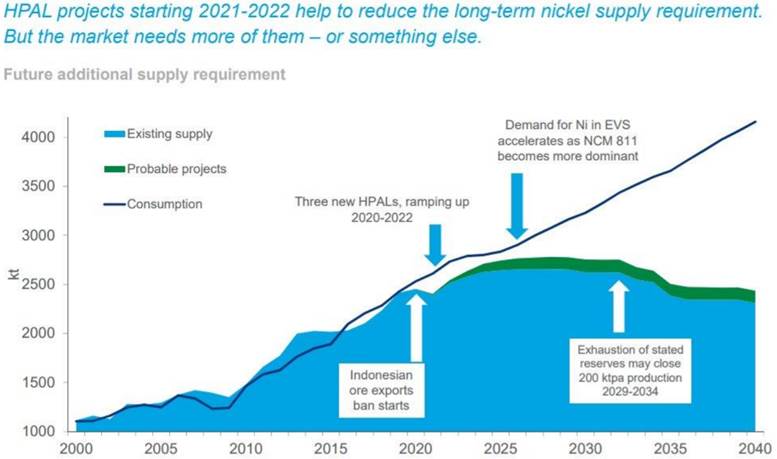

Tsingshan plans to construct an Indonesian plant to produce nickel-cobalt salts from nickel laterite ores. Using HPAL technology (see below) Tsingshan says it will transform Class 2 nickel laterite deposits into Class 1 metal for the battery market.

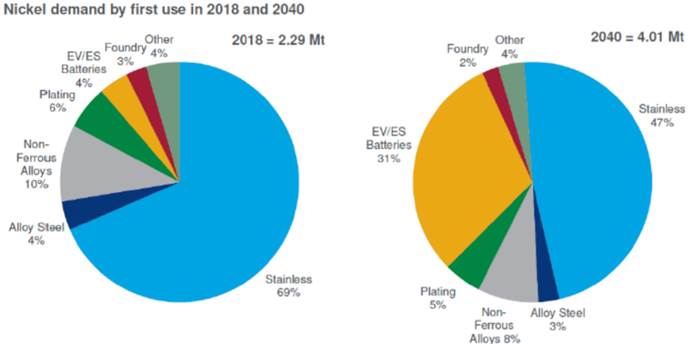

Most of the world’s nickel production, about 70%, is used as an alloying agent in stainless steel. In 2007 when nickel prices ran past $50,000 a tonne, top stainless consumer China balked. Beijing discovered an alternative to pure nickel in the making of stainless steel, called nickel pig iron (NPI). The emergence of NPI revolutionized the nickel industry. The bulk of production shifted from the northern latitudes that host nickel sulfide deposits, to huge nickel laterite belts found around the equator – mostly in the Philippines and Indonesia.

Class 2 nickel is primarily used to make stainless steel, which accounts for two-thirds of global nickel demand. Sulfide deposits provide ore for Class 1 nickel users which includes battery manufacturers. These battery-cos purchase nickel sulfate, derived from high-grade nickel sulfide deposits.

The main benefit of sulfide ores is that they can be concentrated using simple flotation, meaning processing costs are much lower than nickel laterite deposits – such as those in Indonesia and the Philippines.

However, large-scale sulfide deposits are extremely rare. Existing sulfide mines are becoming depleted, with precious few to replace them. It’s important to note that less than half of the world’s nickel is suitable for the biggest growth market – EV batteries.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for Class 1 nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by EV battery suppliers.

The solution seems simple: just mine the laterites to produce nickel sulfate for batteries.

Problem is, there is no simple separation technique for nickel laterites – despite the plant the Chinese are building in Indonesia to do just that. Laterite projects have high capital costs and therefore require large economies of scale to be viable.

The mineralogy is complicated and the processing technology is expensive and not particularly reliable.

Laterite saprolite (higher nickel, magnesium and silica but lower iron content) orebodies are processed with standard pyrometallurgical technology.

A laterite limonite zone that is higher in iron and lower in nickel, magnesium and silica, requires High Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL) technology to extract the nickel; the Caron Process is no longer considered viable.

HPAL – whose performance record has been highly mixed – involves processing ore in a sulfuric acid leach at temperatures up to 270ºC and pressures up to 600 psi to extract the nickel and cobalt from the iron-rich ore; the pressure leaching is done in titanium-lined autoclaves.

Counter-current decantation is used to separate the solids and liquids. Separating and purifying the nickel/cobalt solution is done by solvent extraction and electrowinning.

The advantage of HPAL is its ability to process low-grade nickel laterite ores, to recover nickel and cobalt. However, HPAL is unable to process high-magnesium or saprolite ores, it has high maintenance costs due to the sulfuric acid (average 260-400 kg/t at existing operations), and it comes with the cost, environmental impact and hassle of disposing the magnesium sulfate effluent waste.

Despite the difficulties with HPAL, China is working with Indonesia to develop a huge facility for developing battery-grade nickel Chinese-led, of course. China doesn’t really care about helping Indonesia to become an EV battery hub. Its real goal is to establish a nickel-processing beachhead in the largest nickel producer in the world, using Chinese technology to process Class 2 nickel laterite deposits into Class 1 battery-grade metal.

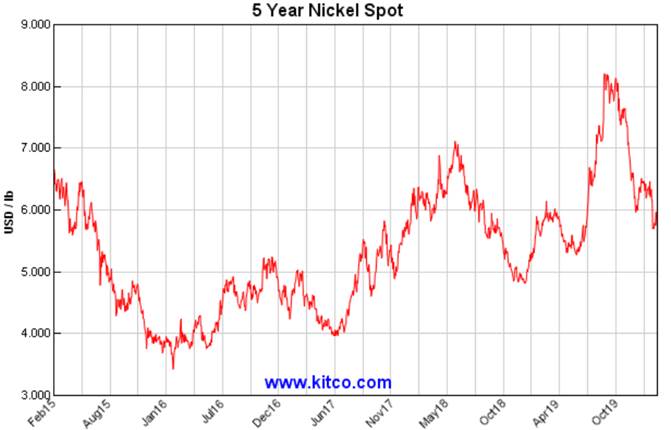

The key point it this: In building all these new nickel processing plants in Indonesia, locking up laterite nickel supply to make nickel sulfate suitable for EV batteries, using the more expensive HPAL, China is setting the stage for a dramatic increase in the price of nickel chemicals. And that means raw nickel prices will have to go up too, because mining companies will no longer be able to profitably mine and process nickel at the current $6 a pound – prices will need to rise, for them to afford the much higher costs of processing laterite nickel deposits into battery-grade nickel – let alone dealing with the greater complexity and waste disposal issues accompanying HPAL.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.