Why Trump’s low-dollar plan won’t work

2019.07.30

The slowdown in the United States, and throughout the world, has led many to speculate that the time has come for an intervention in the US economy.

Despite a healthy stock market and the economy barreling along at near full employment, persistent negative economic indicators have policymakers twitching for some kind of response.

On Friday US Gross Domestic Product numbers failed to inspire. American GDP grew just 2.1% in the second quarter, compared to a 3.1% gain in Q1. One of the most important takeaways from the official report card on the economy, was the value of inventories, or goods waiting to be sold. It shrank by $44.3 billion, Marketwatch reported, knocking a full percentage point off GDP.

A bigger US trade deficit added to the drag on economic output. Imports rose slightly and exports fell 5.2%, due to a strong US dollar, Chinese countervailing duties on exports like soybeans and cars, and a slowing global economy.

Marketwatch’s “Big picture” take on the report was that “Households are carrying the ball while businesses sit on the sidelines.”

Consumer spending, which accounts for a whopping 70% of the economy, jumped 4.3% after a mediocre 1.1% in the first quarter. While Americans are paying for enough goods and services to keep the economy growing, the worry is that businesses will cut jobs or reduce hours if growth doesn’t pick up – “a potential threat to the golden goose known as the American consumer,” Marketwatch said.

In June the country’s manufacturing PMI – an indicator of industrial activity – slumped to 15.6, the lowest since 2009; the auto sector is particularly weak.

Global trade slowed for the seventh straight month in May, and the International Monetary Fund reduced its global growth outlook – already the lowest since the financial crisis of 2008-09 – by almost a point to 2.5% this year.

The ongoing trade war between China and the US is partially responsible for this, as reflected in overseas buyers of American goods taking a wait and see approach.

Big picture: U.S. economy has become like a rowboat with one oar. Services are propelling the economy forward, but the manufacturing sector has basically pulled its oar out of the water. – Marketwatch

Inflation is running at just 1.4%, below the US Federal Reserve’s 2% target. Concerned about the slowdown at home and abroad, in June the Fed decided not to raise interest rates, and strongly hinted that it will cut the federal funds rate (the banks’ overnight lending rate) when it meets on Wednesday, July 31.

“Given the persistent protectionist draft, the lingering policy uncertainty breeze, the sniffling global economy, and the cooling room temperature at home, now may be an opportune time for a Fed immunization shot,” economists Gregory Daco and Jake McRobie told clients in a note.

Our last article took a detailed look at “Quantifornication round 4,” as the Fed gets set for a monetary easing redux, possibly similar to the three rounds of monetary easing that happened from 2008 to 2014 as a response to the financial crisis.

Here we’re turning to the US dollar and the options available to the United States in this low-growth global environment, where dovish stances by central banks are likely to put upward pressure on the greenback, against the stated and implied wishes of the White House.

Trump vs the Fed

Presidents before Donald Trump have favored a strong dollar because it reflects a healthy economy and bolsters foreign demand for US debt. The 10-year US Treasury note is the most popular sovereign debt instrument in the world. That’s because it is understood the risk of the US defaulting on its debt, thereby failing to pay interest to its Treasury bill and bond holders, is practically nil.

Trump has frequently messaged and spoken about how competing currencies like the Chinese yuan and the euro are unfairly low, hurting US manufacturers. He has also frequently chided Fed President Jerome Powell, who since taking over as chairman has presided over a series of interest rate raises. The Fed has raised rates nine times since it started lifting rates in 2015.

Trump thinks the rate hikes are restraining economic growth and are unnecessary because inflation is so low. (Interest rates are usually increased to cool an over-heating economy) He wants to keep interest rates, and the dollar low in order to incentivize US manufacturers to export more, thus improving the US trade deficit with the rest of the world, and particularly, China, whose export-driven economy has for years exported far more goods to the US than the US ships to China.

This goes against the thinking of the US Federal Reserve which has been intent on raising borrowing costs to more normal levels, after they were pushed to near zero following the financial crisis. Read more at Trump vs the Fed: who wins?

It all came to a head in the first quarter of 2019 when stock markets tanked on the suggestion of continued interest rate increases. At that point the central bank’s board of governors took their foot off the accelerator of rate increases, saying they would “be patient” and see how the economy was doing. In June they went further than that, signaling a rate cut is imminent.

Right now the administration is in a dilemma. It looks like Trump will get his way with an interest rate decrease, but the problem is that most central bankers are thinking the same thing. They all want to use rate cuts as a tool for prying more growth out of their lagging economies. In doing so, their currencies will drop, undercutting the US dollar, exacerbating the trade deficit Trump is so keen to re-balance (exports greater than imports). The upshot may well be that the Fed cutting interest rates in an already-low global interest rate environment (over 90% of developed-country government bonds are negative) will have a negligible effect on the value of the dollar, which is currently at a two-year high – measured against a basket of currencies, as indicated by the DXY chart below.

The Triffin Dilemma

However what seems to be lost on Trump and his Treasury Secretary, Steven Mnuchin, is that the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, can only go so low because it will always be in high demand for countries to purchase commodities priced in US dollars, and US Treasuries. Nor should it be allowed to go too low, because that would risk the dollar losing its “exorbitant privilege”.

Because the dollar is the world’s currency, the US can borrow more cheaply than it could otherwise, US banks and companies can conveniently do cross-border business using their own currency, and when there is geopolitical tension, central banks and investors buy US Treasuries, keeping the dollar high. A government that borrows in a foreign currency can go bankrupt; not so when it borrows from abroad in its own currency ie. through foreign purchases of US Treasury bills. The US can spend as much as it likes, by keeping on issuing T-bills that are bought continuously by foreign governments. No other country can do this.

The cost of having this privileged status is the country that has it, must run a trade deficit with the rest of the world. It can’t have the strongest currency, and also keep the currency low in order to increase exports.

This is explained in a previous AOTH article titled The Triffin Dilemma Will Create a 3G World. Here is an excerpt:

When a national currency also serves as an international reserve currency conflicts between a country’s national monetary policy and its global monetary policy will arise.

“In October of 1959, a Yale professor sat in front of Congress’ Joint Economic Committee and calmly announced that the Bretton Woods system was doomed. The dollar could not survive as the world’s reserve currency without requiring the United States to run ever-growing deficits. This dismal scientist was Belgium-born Robert Triffin, and he was right. The Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971, and today the dollar’s role as the reserve currency has the United States running the largest current account deficit in the world.

By “agreeing” to have its currency used as a reserve currency, a country pins its hands behind its back. In order to keep the global economy chugging along, it may have to inject large amounts of currency into circulation, driving up inflation at home. The more popular the reserve currency is relative to other currencies, the higher its exchange rate and the less competitive domestic exporting industries become. This causes a trade deficit for the currency-issuing country, but makes the world happy. If the reserve currency country instead decides to focus on domestic monetary policy by not issuing more currency then the world is unhappy.

Becoming a reserve currency presents countries with a paradox. They want the “interest-free” loan generated by selling currency to foreign governments, and the ability to raise capital quickly, because of high demand for reserve currency-denominated bonds. At the same time they want to be able to use capital and monetary policy to ensure that domestic industries are competitive in the world market, and to make sure that the domestic economy is healthy and not running large trade deficits.

Unfortunately, both of these ideas – cheap sources of capital and positive trade balances – can’t really happen at the same time.” ‘How The Triffin Dilemma Affects Currencies’, investopedia.com

Race to the bottom

To recap, the US president favors a low US dollar in order to make exports more competitive, to narrow the yawning trade gap, and restore American manufacturing which has been hit hard by cheaper foreign currencies. This is the basis of the trade war between the US and China, where tariffs are seen as the best weapon to correct trade balances that go against the US.

Decades of currency stability, when countries had a “gentleman’s agreement” not to competitively devalue their currencies, may be coming to an end. President Trump has accused China, Russia, Germany and Japan of purposely keeping their currencies low. For example the euro has depreciated 1.7% against the dollar this quarter. He hasn’t explicitly said he would devalue the dollar, but he has said the States should match what he says are efforts by other countries to weaken their own currencies:

“Mario Draghi just announced more stimulus could come, which immediately dropped the Euro against the Dollar, making it unfairly easier for them to compete against the USA. They have been getting away with this for years, along with China and others,” Trump tweeted following [ECB President] Mario Draghi’s comment that the European Central Bank may need to reduce interest rates or purchase bonds if inflation in the eurozone continues to lag.

Japan and the ECB have, like the Federal Reserve, employed bond-buying, as well as interest rate cuts – to stimulate their economies, to try and repair the damage caused by the 2008-09 recession.

Now, slow global growth, caused partly by the trade war restricting global shipment volumes, as well as a slower Chinese economy, is bringing back these dovish policies.

The US, China and the European Union are all taking measures to stimulate their weak economies. Japan is also expected to expand stimulus, if inflation falls below its 2% target. The People’s Bank of China has taken steps to boost lending, as a way to jumpstart the economy. Other central banks turning dovish include Turkey, which hacked its interest rate down to the lowest in 17 years, Australia which cut rates for the first time in three years, New Zealand, India, Malaysia and the Philippines.

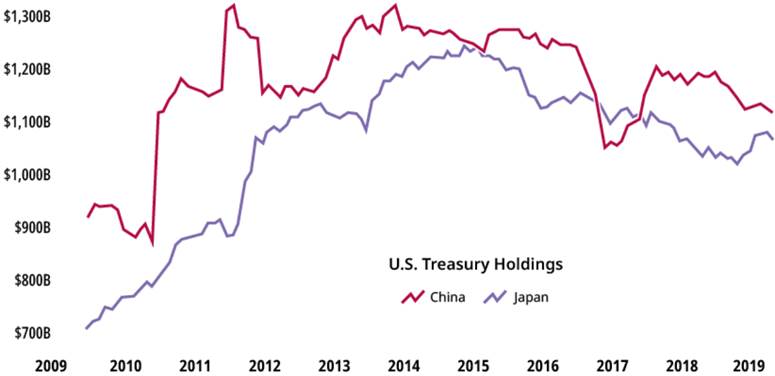

Yet these same central banks are staying away from government bonds with record-low or negative yields. They’re selling Treasuries and dollars, buying gold, and to a lesser extent, yuan, euros and yen.

If the US insists on pursuing a low interest rate and a low dollar, its trading partners will be forced to follow suit and devalue their currencies, in order to keep competitive, and maintain export levels. Reuters agrees:

The impact of looser Fed policy may be felt around the world through a decline in the dollar, which could pressure Europe and Japan to follow suit to keep their exporters competitive – the makings of the tension over currency that has plagued G20 meetings before.

“It is hard to see how you get a cooperative outcome,” said Vincent Reinhart, chief economist at Standish Mellon Asset Management and a former top staffer at the Fed.

“A trade dispute can become a currency dispute pretty quickly. If what the United States ultimately wants is a depreciation, I don’t see others raising their hands and saying I will take the appreciation … We don’t have many trading partners that are in a position to share weakness.”

A race-to-the-bottom currency war is especially dangerous right now because countries are lightening up on Treasuries and dollars. A handful are taking advantage of every opportunity not to use the USD. The dollar’s reserve-currency status is increasingly under threat.

According to the IMF’s last quarterly report, the dollar’s share of global foreign currency reserves in Q2 2019 fell for the sixth straight quarter, to the lowest level since 2013. Tellingly, the start of the fall corresponds to when Trump took office as the 44th president. In January 2017, Trump’s inauguration, the ratio was 65.4%. In the first quarter of 2019 it was 62.5% and in the second quarter it slipped to 62.3%.

We’ve seen central banks, over the last quarter, giving the brush-off to near-negative yielding US Treasuries in favor of bonds that offer higher yields – even risky Greek bonds – and piling into gold, the best safe haven in times of crisis.

And we’ve witnessed more cooperation between Russia and China, through the signing of multi-billion-dollar energy deals and currency swaps that water down the greenback’s influence. For more read De-dollarization has begun

4 ways to depress the dollar

Option 1: Devalue

A currency war, then, started through a direct intervention by the US Commerce Department, to devalue the dollar, is a poor way for the federal government to achieve its objective of lowering the dollar, increasing exports and reversing the trade imbalance. Significant monetary easing including the sustained purchase – for the fourth time in 11 years – of government bonds plus deeper interest rate cuts (QE4), resulting in a lower dollar, may endear the government to manufacturers, but it will also antagonize trade partners, and increase the prices of imports. Higher import costs will likely be passed onto consumers in the form of higher prices. Consumer spending, which represents a massive chunk of the economy, 70%, is one of the bright spots in the US economy, so the government surely doesn’t want to do anything that might hobble the mighty American consumer.

Also, this strategy depends on the Fed to follow through on interest rate cuts should the Commerce Department devalue. Jerome Powell or his successor may decide to make a point of showing the Fed’s independence by either refusing to lower interest rates or raising them. However, top White House aide Larry Kudrow said last week the White House won’t intervene to make the dollar weaker. It’s also worth noting that Powell, the current Fed chair, has clarified it’s not the Fed’s job to influence the value of the dollar.

“The Treasury Department – the administration – is responsible for exchange rate policy – full stop,” Powell said June 25 during a speech in New York, responding to an audience question. “We don’t comment on the level of the dollar. We certainly don’t target the level of the dollar. We target domestic economic and financial conditions as other central banks do.”

Option 2: Sell dollars

The president’s comment that the US should match other countries’ efforts to weaken their own currencies has led to speculation he could order the sale of dollars to push down the value of the buck, especially since the IMF has said it’s at least 6% higher than warranted by economic fundamentals.

“Conditions seem increasingly favorable for the U.S. administration to intervene against perceived (dollar) overvaluation,” Citi economists said on July18, via Reuters.

That could mean the US Treasury sells dollars to buy foreign currencies, through the $126 billion Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) – something it has not done since September 2000, as part of an international effort to prop up the euro which was collapsing at the time.

However critics say because the fund only holds about $22 billion worth of dollars, among other currencies, the overall impact on the dollar’s value would be minimal. By comparison China holds $3.1 trillion in reserves.

Option 3: Ask Congress

Accessing the ESF to unleash a cascade of dollars would require congressional approval. If Trump could somehow convince Congress to agree, which would be next to impossible given the Democrats’ majority in the House of Representatives. Reuters quotes Joseph Gagnon, a former economist at the Fed and the US Treasury, saying that this would entail lifting the legal level of the Treasury’s borrowing authority, allowing the administration to raise more cash to buy forex.

“If you get rid of the debt ceiling, it’s clear the U.S. would win in a currency war,” said Gagnon.

The administration could also do an end run around Congress by declaring foreign exchange intervention “a national emergency”, thereby forcing the Fed to sell dollars from its own account. That’s not at all unlikely for this president who used the same rationale for needing to build a wall on the southern border.

Option 4: Helicopter money

The last option is one that could only be exercised by the US Federal Reserve, which has control over the money supply. Back when Ben Bernanke was chairman of the Fed, he invoked famous economist Milton Friedman, in suggesting the Fed could use “helicopter money” in a 2002 speech.

It refers to the idea of the Fed writing a huge check to the US Treasury, which would then send cash, in the form of tax rebates, to millions of Americans.

In a recent article for the non-profit Brookings Institution, Bernanke again lays out his case for helicopter money, saying that it’s one of the options the Fed has if monetary policy (interest rate cuts) alone is inadequate to support economic recovery or avoid too-low inflation, especially when interest rates are already near zero. Advocates of helicopter money, which Bernanke calls a Money-Financed Fiscal Program, or MFFP, will find his article on the matter good reading, but the upshot is the United States is extremely unlikely to put such a strategy into motion. The former Fed chair nicknamed “Helicopter Ben” states:

To be clear, the probability of so-called helicopter money being used in the United States in the foreseeable future seems extremely low. The U.S. economy has continued to strengthen and is not today suffering from the severe underutilization of resources and very low inflation (or even deflation) that would justify such an approach; and, as I’ve noted, the Fed has other tools still available. Nevertheless, it’s important that markets and the public appreciate that, should worst-case recession or deflation scenarios occur, governments do have tools to respond.

Conclusion: Another way

Instead of trying to suppress the value of the dollar through the four ways mentioned, the federal government could forget about trying to intervene, directly or indirectly, and let the Commerce Department take care of what Trump deems as unfair devaluations.

France24 reports on a proposed new rule that allows the United States to impose tariffs on any country it determines is manipulating its currency.

The Department of Commerce is being given a wide berth to decide whether or not a country is manipulating its currency to the detriment of the United States.

Right now the US Treasury produces a report every six months on whether any country is manipulating their currency to the disadvantage of the United States. A finding of currency manipulation would trigger countervailing import duties against foreign products, that are effectively being subsidized by manipulated exchange rates.

To be clear, this is still a proposal, not a law. But if it passed, it would allow Trump to “have his cake and eat it too,” something which can never be achieved through his current low-dollar ambitions.

Think about it this way: Trump wants a weak dollar, no trade deficit and the world’s reserve currency. Remember the Triffin Dilemma?

The cost of the “exorbitant privilege” that comes with being the world’s reserve currency, is that country must run a trade deficit with the rest of the world. It can’t have the strongest currency, the one everyone wants to buy and hold, and also keep the currency low in order to increase exports.

Instead of fighting with the Fed, of trying to influence a body that is supposed to be independent, would the White House not be better off just allowing the Commerce Department to do what it’s supposed to do, handle exchange rate policy? Let Commerce hit currency manipulators with tariffs, that way the US doesn’t lose out to any country that tries to devalue their money against the dollar.

Keep the dollar strong so that it’s in no danger of falling out of favor as the reserve currency, which may mean raising interest rates, but that’s okay, because a rising yield on short- and long-term Treasuries will attract more T-bill investors. These investors are needed to soak up US deficits and debt; as long as the yield is higher than other countries, foreign investors including central banks will be lining up to purchase your debt, allowing you to keep running up deficits, adding more debt to the $22 trillion pile, as you continue to fund your military adventures, social security, health care etc.

Which Countries Own the Most U.S. Debt?

Having a strong dollar actually allows Trump to have all the things he’s been shouting for: power and prestige abroad, as foreign investors flock to Treasury bills (right now they’re ditching them); cheaper imports which are good for American companies manufacturing abroad, and also for US consumers who will spend more and drive up GDP; and pots of money to spend on all the things Trump holds dear to his heart, like a border wall.

Unfortunately though, the real-estate mogul president is more interested in keeping interest rates low so that mortgage rates also drop, thereby keeping his real estate empire profitable, and to line the pockets of CEOs who must be lobbying the White House not to dare raise interest rates and end the mother of all bull markets.

Like many things this president has tried, his low-dollar mantra will end up being a death rattle when Trump realizes there’s nothing more he can do to keep the currency weak in order to slay his nemesis, the trade deficit. He may as well get used to the fact that as long as the dollar is the reserve currency, it’s going to be stronger than the rest and yes, that means a trade deficit. Live with it.

Instead, Trump is gambling with the currency.

One outcome is a gradual race to the bottom, like a swirling drain. The other is for America’s trading partners to punt the dollar and go with a basket of currencies like Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), possibly backed by gold.

The high-dollar road leads to America being great again, the low-dollar road risks the US falling off its pedestal and becoming a regional power, against a rising China that appears to hold all the cards. Trump is well on his way down the low road, in more ways than one.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.