Why are central banks buying gold and dumping dollars?

2019.06.20

The US Federal Reserve, the country’s central bank, did what many expected on Wednesday, and held interest rates steady, while signaling that a rate cut is on its way.

Despite pressure from President Trump to lower interest rates, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) concluded after a two-day meeting that it will stay pat for now, meaning no change to the 2.25% to 2.5% range on the federal funds rate. Nine of 10 FOMC members voted to keep rates unchanged.

Language here is important. The Fed reportedly dropped its pledge to be “patient” on widely anticipated rate cuts, meaning it could be poised to act. Also, Reuters said, Fed Chair Jerome Powell stopped referring to below-target inflation as “transient”.

Reading between the lines gold traders took the message and ran with it, with the precious metal’s price hitting a five-year high.

Gold runs to $1,366

The result was an immediate jump in the gold price at 2 pm EST, with spot gold spiking to around $1,354 an ounce, then continuing its upward climb to set a new record of $1,360.10 – its best close since Jan. 25, 2018. The rise in gold futures was even more dramatic, with gold for delivery in August rocketing to a fresh high $1,366.60. The last time bullion was priced that high was just over five years ago.

“The Committee continues to view sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective as the most likely outcomes, but uncertainties about this outlook have increased,” the Fed’s statement said.

That’s putting it mildly. Read Dancing close to the exits to learn about all the economic headwinds blowing in America’s direction right now, including weak jobs numbers, trade war jitters, deteriorating business confidence and a yield curve inversion (10-year versus 3-month) which is an almost flawless recession indicator.

In short, everything we as gold investors want to see, along with a falling dollar which is likely to occur as well if interest rates are lopped.

Bonds getting crushed

According to the CME Group’s FedWatch tool, traders are pricing in an 80% chance of a rate cut in July and a 70% of another reduction in September.

Gold’s gains were at the expense of bond holders, who saw the yields on their Treasury bills crumble. The yield on the 10-year benchmark fell to a 21-month low (ie. September, 2017) at one point during the day, 2.017%, before recovering a tenth of a point to finish trading at 2.02%. The 10-year hasn’t fallen that low since Trump was elected on Nov. 8, 2016.

10-year T-bill yields are a key economic indicator, because they gauge investors’ confidence in the economy.

When confidence in the economy is low, investors would rather park their money in bonds than riskier stocks – causing bond prices to rise and yields to drop. When confidence is really low, investors prefer to invest in short-term bonds, knowing the government is more likely to pay them back with interest on a short-term versus a long-term bond.

Long-term Treasuries normally have a higher yield than short-term T-bills, because it takes a higher interest rate to attract investors to stay in a bond for 10 to 30 years. However right now, some yield curves (eg. 3-month, 3-year) have inverted, meaning short-term Treasuries pay higher interest than long-term Treasuries. This is known as a yield curve inversion; it has predicted every recession of the last 60 years, and is therefore closely watched.

Things are even worse in Europe’s sovereign bond markets. Mario Draghi, the president of the European Central Bank, said that “in the absence of any improvement”, referring to low growth and low inflation, more stimulus will be needed to goose the European Union’s economy. That could include interest rate cuts or a return to quantitative easing, where the ECB, like the Fed, prints currency to purchase government bonds.

After Draghi signaled two rate cuts this year as the solution, the euro sunk 0.3% against the dollar, prompting Trump to complain on Twitter that a weaker euro made it easier for Europe to compete against the US. “They have been getting away with this for years, along with China and others,” the president wrote.

However, if the ECB does decide to cut rates, they will be falling further into negative territory – a situation far different from when rates were higher and had more room to drop, post-financial crisis. Hard to imagine too many investors will be lining up for a bond whose rate of interest is actually declining…

But they are. Global tensions such as a potential war with Iran, unresolved trade disputes and anemic global growth, just to name three problems, are forcing investors into safe havens like government bonds, even though their rates are abysmal.

Incredibly, the European Central Bank has already whittled its rates down to below zero, as have four other central banks: Swiss National Bank, Denmark, Sweden and the Bank of Japan. The rates range from -0.1% to -0.8%.

Bond prices have surged and yields have tumbled (the two move in opposite directions) especially in Europe; the yield on Germany’s 10-year bond sunk to a record low, and the yield on France’s 10-year briefly turned negative, Marketwatch reported.

The value of government bonds with negative yields has reportedly swelled to $11.8 trillion, as of June 17. In fact, sovereign debt is more popular right now than tech stocks. “The move is part of a larger trend that saw the [Bank of America Merrill Lynch Fund Manager Survey]’s 79 participants move away from risk and toward positions that reflect fear of a coming economic slowdown spurred by a spreading trade war,” said CNBC.

Clash of currencies?

Trump’s comments re Draghi in Europe and his continual belittling of Jerome Powell – the president reportedly sought a way to fire him for keeping interest rates too high – is actually nothing new.

They are part of a larger plan by the Trump administration to keep interest rates and the dollar low. This is a shift from his predecessors in the White House who have lobbied for a strong dollar.

But for Trump, a low dollar is the way to bring jobs back to the US after many were exported abroad to take advantage of lower labor costs, and therefore rebuild the US manufacturing sector, primarily, through cheaper exports. He’s particularly targeted China for competitively devaluing its currency, the yuan, to dump cheap exports into the US.

Here’s what Trump said on the campaign trail in 2016: “You look at what China is doing to our country in terms of making our product. They’re devaluing their currency, and there’s nobody in our government to fight them… they’re using our country as a piggy bank to rebuild China, and many other countries are doing the same thing.” “Our country’s in deep trouble. We don’t know what we’re doing when it comes to devaluations and all of these countries all over the world, especially China. They’re the best, the best ever at it. What they’re doing to us is a very, very sad thing.”

The question is, have we moved from a trade war to a currency war, and if so, what would that mean? Trump’s comments about Draghi appear to suggest a hardening of his stance against competitive devaluations. (The ECB chief responded, by the way, by saying “We don’t target the exchange rate” of the euro)

But as one commentator writes, Trump is playing a dangerous game that could lead to a currency war, in which countries keep slashing the value of their money in order to gain a trade advantage ie. lower-priced exports.

“Any economy that is suffering from a prolonged bout of undesirably low inflation is likely to favor a weak currency,” Jane Foley, a senior foreign exchange strategist at Rabobank, was quoted by CNN Business. “If several economies find themselves in the same boat coincidentally, the prerequisite conditions for a currency war are set.”

A communique from a G-20 meeting earlier this month states that finance ministers and central bankers have agreed that a currency war is in no country’s interest, and reaffirmed a commitment to refrain from competitive valuations.

However Trump, never one to bow to convention, could easily break the toothless commitment. A Bloomberg article on the subject notes that if the euro keeps dropping it may incite Trump to follow through on a threatened tariff on imported cars and car parts from the EU. Presumably the same spiral of currency devaluations and tariffs could apply to the China-US trade war, if China decides to devalue the yuan to gain an advantage over the US.

Central Bank gold buying

Along with the expectation of a looser economic policy, ie., lower interest rates, the gold price is also currently being supported by major central bank buying. The buying is taking place at the expense of US Treasuries.

Why are they buying? Gold prices usually go up when real interest rates turn negative, in other words, when interest rates minus the rate of inflation go below zero. While we aren’t there quite yet, taking a look at the 10-year benchmark Treasury yield reveals a rate of interest that has been dropping for some time.

Central banks purchase US Treasuries to bulk up their foreign exchange reserves. They do this especially during periods of unrest, or when the economic forecast is bleak. Gold’s role as a safe haven is well-documented. Of course Treasuries are as much or more sought-out by investors in a crisis or pending crisis, but lately, Treasuries have become much less popular as a means of storing wealth.

The reason is simple: T-bills don’t offer a good return, and neither do other sovereign debt instruments – as mentioned, five important central banks are offering negative rates.

Looking at the 10-year yield chart, we see the yield starting to go down last November, falling steadily all the way to its current 2.02%. Subtract 1.8% inflation and the yield, just 0.22% begins to look pretty skinny.

There’s an old saying on Wallstreet “Six percent interest will draw money from the moon.” And it’s true, but what is also true is 1. As long as real interest rates are below 2% gold is in a bull market and 2. Real interest rates below 2% draws investors to gold.

Central banks know this, so do educated gold buyers.

With Treasury notes paying such low net yields, gold becomes an attractive investment. And while the precious metal offers no yield, its status as an inflation hedge and store of value not subject to fiat currency manipulation are good reasons for central banks to purchase gold.

It doesn’t take an economist to see what’s happening here. Central banks see Treasury yields slumping and real yields low, and likely on their way negative, so they are backing up the truck for gold. They see gold continuing to increase in value.

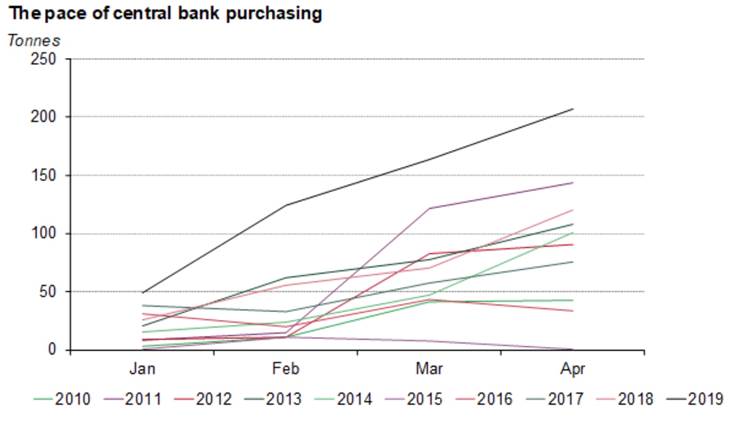

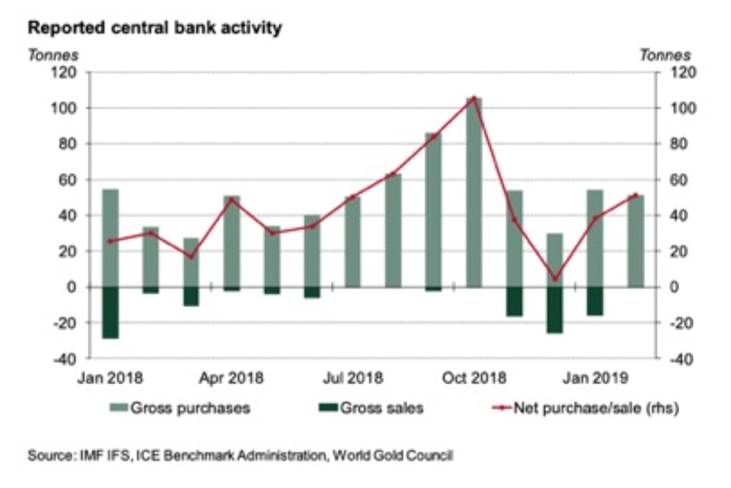

According to the World Council, central banks are continuing a buying spree that stretches back to 2018. A total of 651 tons of gold was accumulated last year, 74% more than 2017 and the highest amount since the end of the gold standard in 1971.

So far in 2019, central banks have squirreled away 207 tons in bank vaults, the highest year-to-date purchases since central banks became net gold buyers in 2010. (before that they were net sellers, selling more gold than purchased).

On a quarterly basis, central banks bought way more gold in the first quarter of 2019 than Q1 2018. The WGC reports first-quarter purchases were the highest in six years, rising 68% above the year-ago quarter. It was the strongest start to a year for gold buying since 2013.

Russia and China were the top two purchasers, particularly Russia which has been trying every means available to diversify away from the US dollar – such as selling US Treasuries and signing energy deals with China whereby the transactions are in yuan or rubles, not USD. The Central Bank of Russia loaded up on 274 tonnes.

China has increased its monthly gold purchases by nearly 50%, to 15 tonnes a month, according to Kitco, with the Philippines’ central bank announcing plans to buy up to 30 tonnes of bullion a year. Other leading purchasers were Turkey, Kazakhstan, India, Iraq, Poland and Hungary, the World Gold Council report states.

The annual survey also said none of the central banks plan on reducing their exposure to gold over the next year from May, with 18% saying they plan to increase their bullion holdings.

The 2018-19 gold-buying spree is being driven by the de-dollarization of countries like Russia, China and Turkey which have an axe to grind with the US. They want to get out from under the thumb of Uncle Sam.

Forbes notes central banks’ motivations for buying gold are different than they were in previous decades when the financial system was back-stopped by gold:

In the distant past, central banks had to buy gold because of its vital role in the global financial system. Now they are choosing to do so because they are worried about the dollar. In other words, they’ve been scared into this bullion buying binge.

For more on this subject read How central bank gold buying is undermining the dollar

Jeff Christian, managing partner at CPM Group, a New York-based commodities consultancy, agrees. “Today central banks are buying gold to diversify their monetary reserves,” says CPM’s Christian. “Most central banks want to diversify away from the dollar.”

He gives the example of Russia where, as Forbes reports, the change may be partly driven by the need to ditch dollars and unentangle their countries from the US banking system.

Dumping Treasuries

Central bank gold buying is only one half of the equation we are presenting. The other half is the buying and selling of US Treasuries. Is it safe to assume that if central banks are buying gold, they are also selling, or buying, less Treasuries? If only it were so simple.

Russia and China certainly fall into that category. The Central Bank of Russia sold 85% of its Treasuries last year while at the same time loading up on gold. China resumed adding gold to its reserves last December (and has continued to do so) while at the same time it dumped $69 billion in Treasuries in 2018.

However, foreign investors of US debt, including central banks and private companies, reportedly raised their holdings of US Treasuries between April of last year and April of this year, by $253 billion, to a total of $6.43 trillion.

Here’s where it gets complicated. Wolfstreet tells us that over the same period, the US national debt climbed by $960 billion to around $22 trillion. So the share of the debt held by foreign investors actually dropped to 28%, from 34%.

That means some other entities must have bought the $707 billion difference ($960B minus $253B). According to Wolfstreet, of the $22 trillion national debt, foreign investors including central banks only own $6.4 trillion. The majority of US government paper is held by US government entities, which piled on $102 billion, and American institutions and individuals, which bought a whopping $876 billion in T-bills, year over year until April 30. This latter group represents $7.6 trillion of the national debt, or 34%. The remaining $5.8 trillion is held by US government entities, with the Federal Reserve owning just $2.1 trillion.

The two takeaways here, are that since 2015, foreign debt holders have been gradually moving away from T-bill purchases. Whereas the percentage of the national debt owned by foreign entities rose almost every year from 2001 to 2015, since then, it has gradually dropped, to 28%. And second, it’s American institutions and US citizens who own most of the country’s mounting pile of debt, not central banks or the Federal Reserve.

Conclusion

The US dollar is the most important unit of account for international trade, the main medium of exchange for settling international transactions, and a store of value for central banks.

Yet central banks no longer consider the USD the “gold standard” of foreign exchange. As large Treasury holders like China and Russia “de-dollarize” in favor of other debt instruments that don’t tie them to the US banking system, the dollar is losing its “exorbitant privilege” we have written about before. Gold is the beneficiary of this change.

Central banks backed up the truck for gold in 2018, buying 651.5 tonnes versus 375 tonnes in 2017. That’s the largest net purchase of gold since 1967. And the buying spree appears to be continuing.

Wednesday’s spike in the gold price shows that gold is the play for investors right now. We know that gold prices go up when real interest rates go negative. The net 10-year yield hasn’t yet gone below zero but it’s pretty close, currently 0.22%. Central banks have some very smart people working for them. They see real yields dropping, a yield curve inversion predicting an energy spike (war with Iran) and gold climbing. Why buy a bond that pays you 0.22% real interest, or possibly going to a negative rate of interest?

As we see it, things are only going to get worse for Treasuries and better for bullion. Think about it. We have a number of indicators pointing to an economic slowdown, both globally and in the US. We have an inverted yield curve on 10-year/ 3-month Treasuries); inversion presages a recession within 14 months with almost 100% reliability. There are several hot spots in the world that boost safe haven demand, like Iran, the South China Sea, Yemen, just to name a few. We have an unresolved trade war with China and a revised NAFTA agreement that has yet to be ratified. A trade fight between the US and the EU over autos is also brewing. Central banks are dumping Treasuries and buying gold. There’s a global movement afoot to increase stimulus to goose flagging economies, evidenced by low inflation. If the Fed does go ahead and lower rates, the dollar will follow suit. It may keep falling if a currency war ensues, which becomes more and more likely the longer we go without a China-US trade deal.

Unless something drastic happens, like Trump finding religion in “Xism”, or backs off on Iran (Iran shot down a US drone, the US is going to retaliate), or the Fed reverses course and raises interest rates, it’s the perfect storm for gold.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.