Venezuela trying to sell gold to stay afloat

2019.02.02

Venezuela is reaching for its last card as the deck collapses on President Nicolas Maduro’s failed regime.

The country is selling its gold in order to provide liquidity for imports of basic goods.

You know your regime’s days are numbered when you start eyeing your bullion. Indeed gold’s status as store of value, as money, the only currency available when yours is worthless, has come into play with respect to the crisis that has been unfolding in Venezuela over the last couple of years and appears to be reaching its peak.

The mysterious plane

On Tuesday a Venezuelan politician tweeted that a Russian Boeing 777 had landed in Caracas intending to transport 20 tons of gold stored in the central bank.

While Jose Guerra couldn’t provide any evidence of the bullion haul worth about $840 million, or 20% of its central bank reserves, Bloomberg confirmed it. “Separately, a person with direct knowledge of the matter told Bloomberg Newsthat 20 tons of gold have been set aside in the central bank for loading,” the news outlet reported.

On Friday however the Maduro regime canceled the shipment.

Where could the gold have been going? We don’t know but we can make an educated guess, based on Venezuela’s recent gold transactions. Swiss trade data (Venezuela used to sell gold to Switzerland) reveals that Venezuela exported almost 100% of $2 billion in gold exports, over the last two years, to Turkey and the United Arab Emirates ($1.1 billion to UAE and $901 million to Turkey). In November the country was reportedly planning to sell 15 tonnes to the UAEin return for cash euros; Russia has also received Venezuelan gold.

We also know that one of the private jets spotted in Caracas this week belonged to Ciner, a Turkish mining company. Turkish President Erdogan is one of Maduro’s only friends these days, as Venezuela slips further into chaos with reports of extreme hyperinflation and mass unemployment. According to Australia’s news.com.au, a roll of toilet paper worth A$0.55 costs 2,600,000 bolivars. The government is so desperate for cash, it can’t even afford to print its own currency.

Venezuela’s trade in gold with Turkey is raising suspicions the bullion is ending up in Iran – in violation of US sanctions. Ankara has been warned to stop “sanctions-busting”.

Maduro’s earlier failed attempt to take Venezuela’s gold out of the UK is further evidence that the Russian plane story is true. The Bank of England reportedly blocked him from taking US$1.2 billion out – from Venezuela’s $8.4 billion total gold reserves, estimated by the World Gold Council.

The embattled Venezuelan president’s hold on power is looking very tenuous. The US, UK and several European countries have publicly supported National Assembly leader Juan Guaido as interim president. On Monday the United States slapped sanctions on Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PdVSA, which the US believes to be a vehicle for embezzlement. The oil sanctions are expected to affect about $7 billion in assets immediately, and another $11 billion this year, CNN said. US purchases of Venezuelan oil will be blocked.

The Russian connection

So where was the Russian plane planning to go with 20 tons of gold? A little research shows that Maduro needs financial support from Russia, and is using the only thing he has left as collateral for borrowing more: bullion.

The Kremlin loaned the country about $3 billion in 2017, but compared to Venezuela’s $120 billion debt, it’s a drop in the bucket. The New York Times reports Russia lent Venezuela $10 billion from 2013-17, for a price: oil and influence. Last year the biggest oil company in the world, state-owned Rosneft, bought nearly half of Citgo, PdVSA’s refining subsidiary in the United States. The purchase was collateral for a $1.5B loan the Kremlin made to PdVSA.

The Citgo deal was part of a strategy by Russia to use Rosneft to achieve foreign policy objectives:

Rosneft’s investments have also been focused on Cuba, China, Egypt and Vietnam, and it has been seeking deals around the eastern Mediterranean and Africa, areas where it contends with American interests. Using its oil company as a geopolitical tool has given Russia more running room at a time when Western sanctions weigh heavily on its economy. – The New York Times

For Venezuela, the loans avoided a debt default, while helping Rosneft to lessen the pain of US and European sanctions against the company. In fact Russia has become Venezuela’s new banker, states New York Times, replacing China, which has given up making loans. PdVSA used the Russian money to keep producing oil.

Also, both Russia and China use oil as currency. They both accept payment of Venezuelan oil in exchange for debt repayments. Good for Venezuela, since it avoids having to dip into foreign exchange reserves.

Knowing all this, the Russian plane parked on the tarmac in Caracas waiting for 20 tons of gold begins to make more sense.

The Monroe Doctrine

It does seem strange though, that Russia is so flagrantly meddling in Venezuela, a country clearly within the US zone of influence.

In the 1800’s the United States under President James Monroe invoked the Monroe Doctrine, which stated that any effort by European nations to control any independent state in North or South America would be viewed as “an unfriendly disposition towards the United States.”

The intent of the Monroe Doctrine was to free the newly independent colonies of Latin America from mostly Spain and Portugal, so that the States could exert its influence undisturbed.

Since then the Monroe Doctrine has at times been invoked when US interests in its own backyard were threatened – sometimes going as far as regime change.

A recent book by Foreign Affairs contributor Lindsey O’Rourke notes that the US attempted 18 overthrows of Latin American governments during the Cold War, 10 of which saw US forces assume power.

The States was accused of instigating a coup in Venezuela – an allegation the US denies – and trying to assassinate Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chavez.

As for current US interests in Venezuela, we know that President Trump considered invading Venezuela in 2017 but was talked out of it by his national security advisor and others in his cabinet.

We also know that US geopolitical interests have been threatened recently by Russia which in December landed two nuclear-capable “Blackjack” bombers. This was a way for Russia to shore up support for a key ally and its top oil supplier, but it was also a means of provoking the US – a violation of the 200-year-old Monroe Doctrine.

We also know that US geopolitical interests have been threatened recently by Russia which in December landed two nuclear-capable “Blackjack” bombers. This was a way for Russia to shore up support for a key ally and its top oil supplier, but it was also a means of provoking the US – a violation of the 200-year-old Monroe Doctrine.

The Kremlin is trying to take advantage of a weak regime by cozying up to Maduro, offering financial aid and military support, thereby gaining influence in the region.

The Orinoco

The lingering question though is, why does the United States care so much about Venezuela? The media reports this week are full of quotes from US officials saying they want to free the suffering Venezuelan people from a corrupt regime; we’ve heard this from the US many times before.

At Ahead of the Herd, we’re a little more cynical, and we always follow the money. A little digging reveals some interesting truths.

At the end of December Oilprice.com reported a confrontation between the Venezuelan navy and two Norwegian ships conducting seismic work in the waters off Guyana – next door to Venezuela.

The US jumped to Guyana’s defense, saying the Venezuelan navy was being aggressive. Why should they care? Because of what lies under the surface. As Oilprice.com reports:

The move comes as ExxonMobil and its partner Hess Corp. are spending heavily to develop a string of oil discoveries off the coast of Guyana. The discoveries encompass some 5 billion barrels of oil reserves, and offshore Guyana has quickly jumped to the top of the priority list for ExxonMobil. As such, Guyana – a very small and poor country on the northern coast of South America – is home to one of the most active and attractive offshore plays in the world.

In early 2018, Exxon unveiled a spending plan that would allow the company to significantly increase oil production by 2025, after years of stagnating output. Exxon’s sterling reputation among shareholders has taken a hit in recent years as it has struggled to grow, and some of its peers have caught up to the supermajor. In fact, many analysts now see some of Exxon’s rivals as a much more compelling investment.

Exxon’s strategy to boost profits and expand production hinges on two key upstream targets. The first, the Permian basin, comes as no surprise because every other oil company seems to be betting their fortunes on Texas shale. The second, however, is offshore Guyana.

The US government protecting American oil companies? You don’t say. If the States can help bring a pro-American government to power in Venezuela, it will assist big oil companies in tapping into the largest oil reserves in the world.

We find it especially interesting that Exxon is heading to offshore Guyana for its next oil score. US shale oil is heading for a fall in the next few years due to the high depletion rate of shale wells. Producers have to pump more oil, faster, just to keep up, a phenomenon known as “The Red Queen Syndrome”.

Putting a pro-Western government in power would also help to develop the Orinoco Belt – a heavy and extra-heavy oilsands region the size of Costa Rica. Venezuela has 298 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, the largest in the world; most are in the Orinoco. Not only is there a lot of oil, it’s also easier and cheaper to produce than Canadian oilsands, because it doesn’t contain bitumen, the oily sludge that is hard to process.

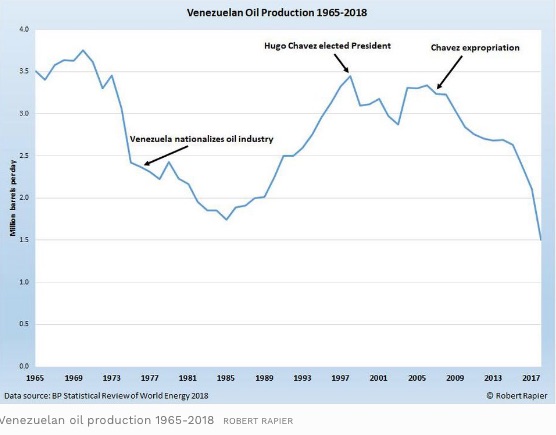

But the oil is still expensive to extract (like Alberta, it has to be open-pit mined or pumped to surface using horizontal directional drilling). In the 1990s Chavez brought in foreign companies for their technologies, but in 2006-07 he took control of the industry, despite big investments from ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips and BP. He gave PdVSA 60% of the four best projects in the Orinoco, enforcing the order by sending troops. Exxon and Conoco walked away and sued (eventually getting compensated), while the others stayed, content to hang onto 40% stakes, the Financial Times reports.

The flight of foreign oil companies and technology, along with the Chavez government’s failure to appreciate the level of capital expenditures required, meant that Orinoco’s output declined.

According to Forbes, Venezuelan oil production has slumped to 1.5 million barrels a day, just over half of what is was before 2006.

Conclusion

What do you do when your country is falling apart? If you’re Venezuelan President Maduro, you find bullion to sell, or use as a bargaining chip. This is a sad state of affairs especially for the people who must be enduring a monetary hardship the equal of Weimar Germany. But on the other hand, it’s a solid vindication of gold. You don’t see Maduro trying to sell bitcoin to pay the bills.

Gold is often criticized by Wall Street as being kind of a useless investment. Institutional investors tend to prefer investments that are thought to contain the potential for growth, growth = sprouts. An investment has to produce a growing revenue stream – if it doesn’t grow it doesn’t compound. So gold is rejected as an investment because it doesn’t produce sprouts, meaning the steady income and systematic growth so sought after by institutional investors just isn’t there.

But that’s not why we the people should own gold. Gold is insurance.

Gold gives all of us something that fiat paper money, or any other financial innovation, cannot deliver in times of the turmoil – escaping Nazi Germany, or buying food, medicine, water or even toilet paper in a crisis – like Venezuela is going through.

What do you do when your paper money is worthless? You sell, barter and trade your gold. Just like Maduro.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd is on Twitter

Ahead of the Herd is now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd is now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.