Thucydides Trap and gold

2019.06.13

When an emerging power attempts to supplant a hegemonic power in international politics, major conflict often ensues. This is the definition of “The Thucydides Trap” as explained in a recent op-ed piece in The Japan Times.

The Thucydides Trap (pronounced “thu”, like you have a heavy lisp + sid + idees) is a term invented by Graham Allison, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Alison has been saying since 2015 that war between a rising power, China, and an established power, the United States, is inevitable, based on historical examples. The argument is fleshed out in his book, ‘Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’sTrap?’

Allison’s Thucydides Trap has become a popular topic of conversation among the chattering classes in these troubling times in America, especially with a loose cannon like Trump as the tweeter-in-chief who has the keys to the nuclear button. As positions in the trade dispute get more entrenched, and issues like Huawei crop up, many are talking about a march to war with a new adversary: China.

Steve Bannon famously stated that he sees such a war as inevitable within five to 10 years. Trump campaigned on a promise to address the widening trade deficit between the two countries. He complained about the low Chinese currency, the yuan, hurting US manufacturers. Jobs were leaving for lower-cost jurisdictions like China and Mexico.

War almost certainly wasn’t on Trump’s mind when his administration began implementing a series of tariffs, initially for aluminum and steel. A little over a year later, however, the extent of the tariffs and the antipathy between China and the US have spread considerably; tariffs now encompass over half of the roughly $500 billion in goods that China exports to the US, and almost all American goods imported by China.

A large part of the trade impasse is over protection of intellectual property rights and access to the Chinese market of 1.3 billion consumers. This is underpinned by the need to be first in technology ie. the leader in production of semiconductors, smart phones, cellular networking (5G), robotics, artificial intelligence, etc.

It’s not that big of a leap to go from a clash of economics to a serious conflagration that results in a shooting war. The US pulled out of the INF Treaty restricting intermediate-range nuclear missiles, so we already have an arms race building between the US, Russia and China. We correctly predicted rare earths could be used as pawns in the trade war. Building missiles and other military hardware requires rare earth elements – simply put, China has them and the US doesn’t.

We also have heightened tensions in the South China Sea, which China claims as its own and the US insists is an international waterway; over Taiwan, a chunk of the former Chinese empire that went independent, but that China considers part of its territory it will fight to defend; and over North Korea’s nuclear capabilities.

Defending South Korea is one of the US Military’s most important mandates in the Pacific theater. For China, continued propping up of Kim Jong-un’s regime through strong trade linkages and aid (last year Beijing said it will invest $88 million in the North’s infrastructure such as a new border bridge), serves to consolidate Chinese power in North Asia, and to prevent a major refugee crisis should the North and South unite as East and West Germany did in 1989.

At Ahead of the Herd, we’ve been talking about a potential war between China and for over a year. It’s not news to us. What is new, is the “mainstreaming” of the topic. In this article we ask the question: How likely is it that the US could go to war with China?

To tackle this question, we need to first look at the current situation the world’s two superpowers find themselves in. Next, an admittedly academic exercise, but very interesting to run through, as to what could happen. Here we take a dive into The Thucydides Trap. Then a discussion of how war could be avoided. And finally, what can investors do to protect themselves?

The great leap over poverty

Forty years ago China was an economic backwater. Despite being the dominant landmass in North Asia, and butting up against “the Evil Empire” Russia, nobody paid much attention to communist China. Southeast Asia was contained following the bloody, divisive conflict in Vietnam. American troops were in Korea. At the time the only threat coming from Asia was cheap Japanese cars.

2018 marked the 40th anniversary of China’s economic reforms and opening-up policy led by Deng Xiaoping, China’s forward-looking president who took over after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976.

Comparing the China of 2018 to the China of 1976 yields some astonishing figures. The first is how successfully China has rid the country of poverty. In ‘78 90% of the Chinese people lived on $2 a day, what the World Bank considered “extreme poverty”. The Chinese government may have wanted to end its isolationist policy under Deng, but it wasn’t too interested in raising the living standards of its citizens. People living in extreme poverty are more worried about their next meal than fighting the government, which is just the way the Communist Party liked it. China had its peasant-led revolution, the party didn’t want another.

Gradually though, reforms did occur, and Chinese citizens began to earn more. Now, only 1% of people live below the poverty line; 800 million have seen their incomes rise above it. According to the Chinese government (admittedly a questionable source), 250 million people in rural China lived in poverty in 1978, compared to 30 million at year-end 2017. The poorest residents saw an incredible 50-fold increase in their standard of living.

“Between 1981 and 2004, China succeeded in lifting more than half a billion people out of extreme poverty, said Robert Zoellick, then-president of the World Bank. “This is certainly the greatest leap to overcome poverty in history.”

With that massive improvement in living standards, China’s economic power has grown at warp speed. Bloomberg notes that in 1978 the country represented 1% of the world’s GDP; by 2017 it was 15%.

We all know the story of what happened to China in the 2000s. Its GDP raced along at double-digits for nearly a decade. The country became the largest commodities consumer in the world, the most important market driver of raw materials like copper, iron ore (used in steelmaking), coal, oil and soybeans.

Today, anybody who knows anything about commodities keeps a close eye on China.

China’s open-ness to world trade meant that in 2001, it was let into the World Trade Organization – effectively earning the country membership into the Western club of developed nations. Those nations, particularly the United States, presumed that China would thus become more “Westernized” and respect the status quo. In fact, what has happened, is that China has taken over a lot of what the US used to control.

For example, at the beginning of the 21st century, the US was the dominant trading partner of every Asian nation; now that position belongs to China. According to Allison, the Harvard prof and conceiver of The Thucydides Trap, this is like a red cape to a charging bull. Ruling powers do not like to be challenged.

“When a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power, this creates a dangerous dynamic in which both the rising and ruling powers are vulnerable to third-party provocations that would, in normal conditions, be inconsequential or easily managed but that can trigger a spiral to a result neither of the primary competitors wanted,” Allison told the 2019 Harvard Alumni China Public Policy Forum in Beijing this March, in a speech titled ‘How to Escape the Thucydides Trap’.

The Gospel of Xi

It might be hard for Westerners to understand the Chinese perspective. We know the Chinese government wants to have better lives for its citizens, to become richer, to have better jobs, higher-educated kids, more brand-name stores, etc. Essentially, to become more like us. Isn’t that the goal of every developing nation? Well yes, and no.

In China’s case, it goes much further than that. Chinese leaders see their country as a lost empire that needs to be regained, respected, both loved and feared. They want China to assume its rightful place in the world; for them, this means the most powerful, envied and emulated nation on earth.

Back in 2014, before all this hubbub over tariffs, an important book was published in China. It was called ‘The Governance of China’, a collection of political theories by President Xi Jinping.

Chinese media claim over 5 million copies have been sold worldwide, though few in North America have probably seen or read it. Perhaps they should though, as it contains some valuable insights into the mind of China’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping.

In the West we tend to think of our leaders as temporary. Not so in China. Last year the Chinese Communist Party voted to abolish presidential term limits, allowing Xi to stay on indefinitely as leader, and to implement his agenda. It’s every dictator’s dream.

But a nightmare for the rest of us. In a book review published by The Atlantic, author Benjamin Carlson, Beijing correspondent for Agence France-Press. describes Xi’s ideology, or “Xiism”:

What emerged for me was Xiism—what I’d describe as an ethno-nationalist variant of Marxism, which holds that the people of China are heirs to a unique civilization and a utopian destiny that entitle them to a privileged position in the world. This destiny can only be achieved by following the moral leadership of Xi Jinping, who in his person (due to his birth and upbringing) embodies the virtues of the people and is their champion.

If Xi’s program is duly followed, Xiism promises a pinnacle of prosperity in 2049—precisely 100 years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China—at which point Xi avers that the Communist Party will “solve all the country’s problems” and the Chinese Dream will be fulfilled. China will be “strong, democratic, culturally advanced, and harmonious,” he vows, adding that in his view, “realizing the great renewal of the Chinese nation is the greatest dream in modern history.”

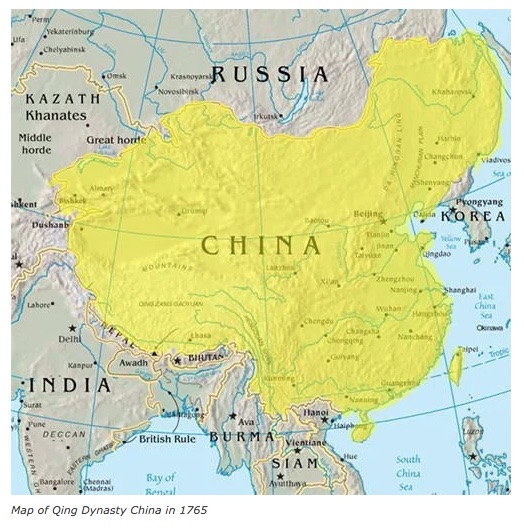

A knowledge of history is important here. Hundreds of year ago China was the undisputed ruler of North Asia. Chinese history is a series of dynasties. The last dynasty was the Qing, or Manchu; the Qing held power for 268 years, from 1644 to 1912. At the peak of its empire the Qing controlled 13 million square kilometers of territory including parts of modern-day Vietnam, Myanmar, Tibet, India and North Korea. Among its major achievements were an expansion of foreign trade, the creation of vast encyclopedias (the Imperial Encyclopaedia written between 1700 and 1725 reportedly contained 10,000 volumes), a large body of literature, development of the Peking Opera, and advances in painting, porcelain and printing.

In this context, President Xi’s recent visit to a rare earths plant, and a speech he made urging comrades to dig in for the long and difficult road ahead, makes perfect sense. The symbolism was clear: Even if the trade war lasts decades, the equivalent of the Long March of 1934 which preceded the emergence of the Chinese Communist Party and Mao Zedong, China will ultimately prevail. When it does, Xi will be the leader of “a new China” in much the same way as Chairman Mao.

Also notable in Xi’s book is the near-complete absence of the United States. In Xi’s world, the US, writes Carlson, is neither friend nor “partner” in non-confrontation. Rather, the US is seen as an insignificant, faraway blip, and countries that China can manage mostly without fear (Russia) or regard benevolently as obedient tributaries (Tanzania) fill the void.

The book is also a testament to the construction of Xi’s persona, and how the state is tapping into both imperial tradition and lingering nostalgia for Red China to present the Chinese leader as everything to everybody: a Marxist messiah for leftists, a people’s emperor for peasants, and a righteous, thundering Jeremiah for urban constituencies fed up with corruption.

This is the Gospel of Xi.

Powerful stuff. There are of course historical parallels. Russia’s diminishment to a middle European power with an economy around the size of France longs, in the hands of a strong leader like Putin, to get Mother Russia back. Annexing Crimea was a good start. Or inter-war Germany which was so punished by the Allies after World War I, that the ground was ideal for National Socialism to take root.

Allison looks at history from a different, though related lens. He believes nations act purely out of self-interest (in this respect he is in the tradition of Thomas Hobbes, who wrote “life is nasty, brutish and short”) and that conflict is pretty much inevitable when a powerful up-and-comer nation is trying to usurp the incumbent country’s dominance.

The Thucydides Trap

This is what Allison refers to as the Thucydides Trap. Its namesake was a Greek historian who gave an account of the Peloponnesian Wars in the 5th century BC, between Sparta, the champion, and Athens, the challenger.

Thucydides concluded “it was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable”. Why couldn’t they just work out their differences? According to the theory it’s this unique situation – where a zero-sum mentality forms in the minds of the pursuer and the pursued, characterized by overconfidence of the rising power, and loss of confidence/ paranoia of the declining hegemon – that causes the powers to fall into the “trap” of war.

Allison combs through 500 years of history to come up with 16 examples of the Thucydides trap; of these, an astonishing 12 examples resulted in war – or 75%.

His main focus is to outline where the US and China are with respect to realpolitik, or practical considerations, and how to avoid war. The signs are not good.

Writing in The Atlantic, Allison states that “Based on the current trajectory, war between the United States and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than recognized at the moment.” That was written in 2015, before the trade war started, so the case for war is even stronger now.

According to Allison, events that could make two nations fall into the trap may be small, “business as usual” conflicts that, if they occurred in a different dynamic, would lead to nothing. For example, the assassination of archduke Ferdinand, a relatively obscure and minor figure, was the spark that lit a whole conflagration of events that plunged Germany, an ascendant maritime power, into war with Britain, whose Royal Navy ruled the seas for decades. Consider the current conflicts between the Chinese and US navies in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. It would not take much – say a collision between two warships – to ignite the powder keg of war.

However, for the threat to be taken seriously, the rising power must have the capability to take on the incumbent power. Henry Kissinger, the US former secretary of state, wrote that “once Germany achieved naval supremacy … this in itself – regardless of German intentions – would be an objective threat to Britain, and incompatible with the existence of the British Empire.”

Again the current situation doesn’t bode well. China has bulked up its military and it now spends more on its armed forces than any other country in the world except the United States. And changes are occurring with China’s military institutions. In a feature article titled ‘The China Challenge: Marshall Xi’ Reuters writes that President Xi has refashioned the People’s Liberation Army, the PLA, into a force that is rapidly closing the gap on US firepower. In fact, the US could even lose, if the two sides were to meet in combat:

In just over two decades, China has built a force of conventional missiles that rival or outperform those in the U.S. armory. China’s shipyards have spawned the world’s biggest navy, which now rules the waves in East Asia. Beijing can now launch nuclear-armed missiles from an operational fleet of ballistic missile submarines, giving it a powerful second-strike capability. And the PLA is fortifying posts across vast expanses of the South China Sea, while stepping up preparations to recover Taiwan, by force if necessary.

For the first time since Portuguese traders reached the Chinese coast five centuries ago, China has the military power to dominate the seas off its coast. Conflict between China and the United States in these waters would be destructive and bloody, particularly a clash over Taiwan, according to serving and retired senior American officers. And despite decades of unrivaled power since the end of the Cold War, there would be no guarantee America would prevail.

Indeed the US appears to be girding for such a military challenge. Bloomberg reports that the Pentagon has been working to overhaul the “two-war” defense strategy that has been the playbook for the last couple of decades – in other words, preparing to fight one major war as opposed to two smaller conflicts simultaneously. The one-war strategy is rooted in the idea that defeating a great-power adversary like China or Russia would be more difficult than anything the US has done in decades, and is a 180 degree shift from the DoD’s focus on counter-terrorism that has dominated the thinking since 9/11.

The U.S. is now building a force not around the demands of two regional conflicts with rogue states, but around the requirements of winning a high-intensity conflict with a single, top-tier competitor — a war with China over Taiwan, for instance, or a clash with Russia in the Baltic region.

There is plenty of serious thinking behind this shift. The new strategy is meant to signal unambiguously – to allies, competitors and the Pentagon bureaucracy – that the U.S. is now focusing squarely on great-power competition and the immense challenges it presents for a force that has been preoccupied with counterterrorism and counterinsurgency for nearly two decades. It recognizes that America’s military advantages vis-à-vis China and Russia have eroded gravely, and that the Defense Department will need new high-tech capabilities and creative operational concepts to defeat either country should war break out.

Back to Allison, the Harvard prof and author agrees that The preeminent geostrategic challenge of this era is not violent Islamic extremists or a resurgent Russia. It is the impact that China’s ascendance will have on the U.S.-led international order, which has provided unprecedented great-power peace and prosperity for the past 70 years.

For those who doubt that China is big enough or strong enough to displace the United States as the top power in Asia, Allison invokes Lee Kuan Yew, who ruled Singapore for three decades, was a mentor to Chinese leaders since the late 1970s, and up to his recent death, was the world’s most prominent China-watcher.

LKY, as he was known, put the odds of China continuing to grow at rates several times greater than the United States over the next decade or so as “four chances in five.” As for China displacing the US, Singapore’s strongman leader reportedly said, Of course. Why not … how could they not aspire to be number one in Asia and in time the world?” And about accepting its place in an international order designed and led by America, he said absolutely not: “China wants to be China and accepted as such – not as an honorary member of the West.

Allison concludes by asking, where does this rivalry stand today? Right on track. If Thucydides were watching he would say this looks like the grandest rising power I ever saw, accelerating towards the most colossal ruling power I ever saw. Well, we’ve got an unstoppable force and an immovable object. I’m looking forward to seeing the grandest collision of all times. I think that’s what he would say. The strategic rationale, in particular, that gave a picture of what would be U.S.-China relations would be, has collapsed both in Washington and in Beijing.

Other credible sources agree that a confrontation between the United States and China is a very real possibility. The Belfer Center from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government opines:

Today, as an unstoppable China approaches an immovable America and both Xi Jinping and Donald Trump promise to make their countries “great again,” the seventeenth case looks grim. Unless China is willing to scale back its ambitions or Washington can accept becoming number two in the Pacific, a trade conflict, cyberattack, or accident at sea could soon escalate into all-out war.

And economics professor Nouriel Roubini, known for predicting The Great Recession, notes in Project Syndicate that a trade war now threatens to escalate into a permanent state of mutual animosity. This is reflected in the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy, which deems China a strategic “competitor” that should be contained on all fronts.

A full-scale cold war thus could trigger a new stage of de-globalization, or at least a division of the global economy into two incompatible economic blocs. In either scenario, trade in goods, services, capital, labor, technology, and data would be severely restricted, and the digital realm would become a “splinternet,” wherein Western and Chinese nodes would not connect to one another.

Stumbling into war

So how might it happen? According to Allison, it would be the perfect storm of misperceptions or miscalculation, combined with politics, wherein the risk of letting your opponent out-flank you to the right on a national security issue, forces the governing party to become even more hawkish, and take on more risk:

So stack these three things on top of each other, reality, perception, politics, and this creates a huge vulnerability to some extraneous action or some third party action, that becomes a trigger that produces a spiral that produces the war.

Allison argues that, in order to avoid the trap, the two nations need to recognize the danger of a shooting war, then find a way(s) to avoid it. However, not everyone agrees that the Thucydides Trap is the right paradigm for our times, nor that avoiding conflict is the way forward.

In a 2017 op-ed piece published in The Strait Times, Arthur Waldron, a professor of international relations at the University of Pennsylvania, called Allison’s book “baffling academic farrago.” Waldron thinks Allison has “China fever” for his various praises of the Middle Kingdom, and believes that turning the other cheek as Allison suggests the ascendant power should do, is actually a recipe for war.

He compares Obama’s failed “pivot to Asia” during the 2000s – whereby the former administration was unable to stop China from creating fortified islands in the South China Sea, and North Korea from shooting off test missiles – with the Munich Agreement of 1938, that forever tainted Neville Chamberlain, Britain’s then-PM, with the brush of appeasement for ceding Czechoslovakia’s Sudentenland to Nazi Germany. He calls this the “Chamberlain Trap”:

“Appeasement of aggressors is far more dangerous than measured confrontation.” Waldron writes. “Did China become more aggressive in the South China Sea in the 2000s because the Obama administration got tougher or because it went AWOL on the issue? I’d say the latter is more likely.

With China, we might want to be more mindful of the Chamberlain Trap (named after the peace-loving prime minister of England, one of the authors of the disastrous 1938 Munich Agreement that sought to avoid war through concessions), which taught Hitler that the British were easily fooled. That is the trap we are in urgent need of avoiding.

Trade war to currency war

We have been speaking ominously of some type of armed confrontation between the US and China. So far however all the bullets that have been fired have been shaped like dollar signs. The situation as it stands, is we have a trade war, becoming more and more intractable, as it becomes tied to technology (Google said on Wednesday it is shifting production of US-bound motherboards out of China and into Taiwan. Huawei, the Chinese tech giant, is not counting on a trade war settlement and is reportedly shifting supply chains and making other preparations for a prolonged fight.)

Two options at Beijing’s disposal are to sell US Treasuries, of which China is by far the dominant holder, and to “weaponize” the yuan. The US could also devalue the dollar.

A large-scale sale of US debt on the bond market would cause US interest rates to rise, bond prices to tank and yields to go ballistic. The latter would exacerbate federal budget deficits, because interest payments would rise on the national debt.

The US dollar would plummet, as a loss of confidence in the greenback ripped through the global economy.

Regarding devaluation, it has recently come up for discussion whether China should knock down the yuan as a way to pressure the United States into making a trade deal.

While China’s central bank has been pursuing a policy of propping up the yuan’s value as the country shifts from an export-driven to a consumer-oriented economy, Forbes quotes Chen Long, a China economist at consultancy Gavekal Dragonomics, stating it is now in Beijing’s best interest to let the yuan slide:

“The renminbi exchange rate is one of the most powerful weapons Beijing has in the trade war with the U.S.,” Chen wrote in a report. Chen argues that a weaker yuan would support China’s exporters. While China’s importers would be worse off, the benefits outweigh the costs because China is a net exporter. But, more importantly, a depreciated renminbi [aka the yuan] could rattle global markets and, consequently, pressure Trump to switch tack.

We’ve now reached the point in time when both countries would benefit from weaker currencies. Trump has frequently launched into Twitter tirades directed at the US Federal Reserve for keeping interest rates too high, along with the dollar. Trump wants the dollar to trade lower in order to help US exporters, and to rein in the China-US trade deficit – something he has been passionate about doing, since he believes that manufacturing jobs will then migrate back to the US from overseas.

In other words, we’re heading for a currency war. A currency war is what happens when countries intentionally devalue their currencies through their central banks. Increasing the money supply lowers interest rates and the value of the currency, thereby depressing the exchange rate.

Those on the losing end of trading relationships decide to engage in a policy of competitive devaluation. By keeping their currencies low, exports will be cheaper, imports more expensive.

The problem for the United States is that throughout the past several years, the dollar has remained high in relation to other currencies, and that has created a large trade deficit. That’s a problem because the US imports more than it exports – meaning consumers are buying more goods and services from abroad than locally. Exporters face resistance from buyers because products priced in dollars are more expensive.

It is primarily the result of the trade deficit – and especially the trade deficit with China – that prompted the Trump administration to start a trade war with China.

Who would win a currency war between the US and China?

On the one hand, devaluation would be good for China’s exports, but on the other hand, Chinese companies importing American products must shell out more yuan to get the same number of dollars as before the currency got devalued. The extra cost would probably be passed onto consumers. China exports to the US much more than it imports from America, though, so on balance, this strategy of “weaponizing the yuan” would favor China.

For more on this subject read How China wins trade war

The wrong kind of president

The Thucydides Trap posed by Prof. Allison is a good model for analyzing great-power relationships, but it’s on “how to avoid war” that the paradigm breaks down. The reason is that avoiding war and trying to find accommodation turns on highly skilled diplomacy. To be blunt, this administration doesn’t have it.

The first problem is that Trump, not surprisingly given his business background, thinks he can solve all foreign policy quagmires by sitting down “mano a mano”. This isn’t the way diplomatic relations between countries is supposed to work. The Washington Examiner explains:

Although the president’s job is, in part, to build strong and lasting relations with other world leaders, those relations should be professional rather than personal. Indeed, that the president would refer to adversarial foreign leaders as “friends,” never mind that his own advisers have identified them as threats, is alarming and points to a lack of understanding of volatile foreign relations.

The other issue with this approach is it presumes no continuity between administrations. The next administration after Trump’s will be dealing with another president (assuming it’s not him).

This partly explains why the Trump administration really has no game plan when it comes to statecraft. If Trump has a strategy in dealing with Beijing, nobody, except him, knows what it is.

Kumi Miyake, president of the Foreign Policy Institute and research director at Canon Institute for Global Studies, fleshes this out nicely in a recent op-ed published in The Japan Times. He takes the Thucydides Trap in a different direction though, writing that the problem with not having a strategy is the risk of appeasement or of taking your eye off the ball:

The real danger now is that there seems to be no coherent and prioritized national security strategy inside the Trump White House. If such a situation continues, the United States may not be able to properly respond to and deal with the next crisis in which China or any other rising powers may be involved.

This is not a crisis caused by the Thucydides’ Trap. Rather, it is a crisis either by the “Chamberlain’s trap,” which led to the disastrous Munich Agreement and eventually to World War II, or by the “power vacuum trap,” in which an established power gives a rising power an easy chance to fill the vacuum and dominate the theater.

Either way, the established power will lose the game after fighting unnecessary wars or even without fighting. This is the real danger for an established power facing a rising power. To avoid these traps, all you need is a coherent and professional strategy under a non-impulsive, well-informed and disciplined president.

We certainly don’t see the Trump administration appeasing China, but we do see the fallout from its hard-line approach to Beijing. A recent example is Mexico planning to hold “high-level meetings” with Chinese officials, in the wake of Trump threatening to bash Mexico with tariffs if the country failed to stem immigration from South America.

Or the cavalier way Trump treated Canada, by slapping aluminum and steel tariffs on the US’ second-most important trading partner, ripping up NAFTA, and snubbing Ottawa – two and a half years into his mandate, Trump has still not visited Canada. Most new presidents make Canada the first international trip they make after inauguration.

That’s cause for concern, but what is really frightening is how Trump deals with problems seemingly with no consultation, no briefing, and no thought to the consequences. In statecraft, this is dynamite. Imagine Trump negotiating his way through the Cuban missile crisis, or the Iran hostage incident. Foreign governments aren’t usually keen to “make a deal” when politics and religion are on the line. These situations require a deft touch, not a sledge hammer.

In May, Foreign Policy Magazine detailed the dangerous escalation the White House is pursuing in Iran – now the subject of renewed US sanctions for its refusal to dismantle its nuclear energy program:

Thousands of U.S. troops and Iranian-backed forces operate in close proximity to one another in Iraq, Syria, and the crowded waters of the Persian Gulf. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates continue to pursue their air campaign against Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen despite international outrage over the world’s worst humanitarian disaster there. And Israel regularly conducts military strikes against Iranian arms shipments and infrastructure in Syria. In this volatile context, the scenarios for an intentional or inadvertent U.S.-Iran war are legion.

If Iran or its proxies respond to U.S. pressure in ways that draw American blood or deal a major blow to critical oil infrastructure in the region, things could quickly get out of hand.

All else being equal, Trump probably doesn’t want another U.S. war in the Middle East. But, if past is prologue, his gut instinct will be to respond (likely via Twitter) to any Iranian provocation with bellicose rhetoric that pours fuel on the fire.

Conclusion: own gold

Nobody can say for sure whether we are looking at an escalation or de-escalation of the affairs of state between the United States and China, but we can say with absolute certainty that it’s a good idea to buy some insurance in case things take a wild turn for the worse. And given Trump’s track record, we should all be nervous.

What do scared citizens do when they fear an economic or political crisis initiated by a renegade leader like Donald Trump? They turn to hard assets like gold.

Indeed gold’s status as store of value, as money, the only currency available when yours is worthless, has come into play time and time again, when tensions heat up.

Gold gives all of us something that fiat currencies (paper money), or any other financial innovation, cannot deliver. Gold is insurance, irreplaceable in its functions.

Moreover, there are a number of demand-side reasons for owning gold right now. They include a series of economic indicators showing that US growth is grinding to a halt; worsening yield curve inversion; a potential trade spat with Europe waiting in the wings, as the US-China trade war appears no closer to a resolution; and the increasing tension between China and the US over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

Take all those factors, add in a flight to safe havens like gold, and you have all the makings of a powerful and prolonged bull market for gold just as we are entering the most active time of the year for junior resource companies.

With all that is going on in the world, we believe the gold price will do well over the next few months.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.