The Repatriators

2019.12.14

The Europeans want their gold back. Amid global trade uncertainty, a pall hanging over the European Union due to continued economic weakness, the exit of Great Britain still a real possibility, and dark, nationalist undercurrents swirling, several of the 28-strong EU members are looking to gold as collateral in the event of a continent-wide “storm” that blows their individual economies into the maelstrom.

The perceived need to diversify away from the US dollar due to the Trump administration-instigated trade war and US snubs against EU members are also pushing Europe towards gold.

The repatriators

This week Slovakia and Poland became the latest European Union countries to call for a repatriation of their gold, which has been stored in Bank of England vaults for decades. Gold reserves owned by Poland and a number of other East European nations were spirited off to London at the outbreak of World War II, amid fears they would fall into the hands of Nazis.

On Thursday the former prime minister of Slovakia called on the country’s parliament to repatriate its gold from the UK because it can’t be trusted with the precious metal.

“You can hardly trust even the closest allies after the Munich Agreement,” said Robert Fico, leader of the socially-conservative Smer Party. “I guarantee that if something happens, we won’t see a single gram of this gold. Let’s do it as quickly as possible.”

The Munich Agreement was the 1938 pact between the UK, France, Italy and Germany that permitted Adolf Hitler to annex part of Czechoslovakia.

Fico’s comments were uttered the same week as Poland repatriated 8,000 gold bars worth £4 billion (USD$5.25 billion) from London to Warsaw, in a top-secret operation involving planes, helicopters, high-tech trucks and specialist police, The Daily Mail reported. Eight night-time flights were made from an undisclosed London airport over the course of several months, shifting the bullion take weighing 100 tons, to un-named locations in Poland.

According to the head of Poland’s central bank, “The gold symbolizes the strength of the country.” Governor Adam Glapinski said at least half of Poland’s 228.6 tonnes will be held in the National Bank of Poland (NBP), with the other half to remain in the UK.

Poland has bulked up on its gold over the past couple of years, buying 125 tonnes, giving it the most gold reserves in the European Union’s east, and 22nd in the world. In its July announcement the NBP called gold the “most reserve” of all reserve assets and an “anchor of trust” that diversifies political risk.

Hungary last October brought back all of its gold reserves from the Bank of England for the first time in 31 years, while at the same time announcing that it had increased its gold holdings by 1,000% (10-fold) from 3.1 to 31.5 tonnes. Romania plans to do the same, evidenced by a bill submitted to parliament by Romanian politicians, specifying that only 5% of the country’s gold can be kept abroad.

About 60% of its 103.7 tonnes are stored at the Bank of England.

In November Serbia made a 9-tonne bullion buy, prompting its central bank governor, Jorgovanka Tabakovic, to say, “We have completed gold purchase transactions and Serbia is safer today with 30.4 tons of gold worth around 1.3 billion euros ($1.4 billion).”

So why is Eastern Europe wanting their gold back now? The answer is chillingly evocative of how Europe looked in the 1930s – divided and economically weak, with angry populations (Italy, Germany) easy targets for national socialism.

According to a recent Bloomberg article, “Gold is all that nationalist leaders in Europe’s east can talk about these days.” It points to Hungary’s anti-immigrant Prime Minister Victor Orban ramping up holdings of gold to boost the security of his reserves, Robert Fico bringing up the detested Munich Agreement, which sold out then-Czechoslovakia to Hitler’s Nazis, as a reason for repatriating its gold, and Poland’s wish to strengthen, via gold purchases, its half-a-billion-dollar economy, as examples of decisions to buy gold being motivated by fear, and some might say, hatred of outsiders.

Consider a statement by Serbia’s strongman leader Aleksandar Vucic, quoted by Bloomberg, that the country’s central bank should buy even more gold than the 9 tonnes it purchased in October because “we see in which direction the crisis in the world is moving.” Which direction is that?

According to Serbia’s central bank the former Yugoslavia region wants to buy gold due to global uncertainty over trade, Brexit and low interest rates that are pushing many real sovereign bond yields below zero, making gold an attractive investment.

Gold is a symbol,” the news service cites Vuk Vukovic, a political economist in Zagreb. “When states purchase it, people everywhere see it as a sign of economic sovereignty.”

Well-known gold commentator Jeffrey Christian agrees that gold repatriation particularly in Europe has a lot to do with the rise of nationalism. The managing partner at CPM Group notes, via Kitco, that countries which have in recent years repatriated their gold or added more to their reserves, such as Germany, Hungary, and Austria, have had a “nasty history of twentieth century nationalism.”

Wirtschafswunder

In 2017 Germany brought home nearly $31 billion of gold bars that had been stored in New York and Paris after World War II. The Financial Times gives a good account of how Germany amassed, lost and then got its gold back.

Perhaps no other country (except maybe Zimbabwe) understands the value of bullion as a store of value than Germany. Hyperinflation during the Weimar Republic of the 1920s had citizens piling near-worthless Deutsche marks into wheelbarrows just to buy bare necessities. During the Second World War Nazi Germany looted about 4 tonnes of gold and stored it in the Reichsbank. But in 1948 the allies recovered it and gave it back to its rightful owners, leaving Germany’s bullion vaults bare.

It wasn’t long however until Germany was again in a position to buy gold. The Wirtschafswunder – economic miracle – of the 1950s and ‘60s allowed West Germany to stockpile large amounts of gold. Under the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, Germany could use dollars, earned by successful export businesses that traded them in for marks, to buy gold at $35 an ounce.

The country managed to accumulate over 1,500 tonnes in the decades that followed. However this gold was not considered safe, with the Bundesbank in Frankfurt only about 100 km from Soviet-controlled East Germany, as told by the FT. It therefore made sense to store its gold in Paris, London or New York. After the fall of communism in 1991, that rationale disappeared.

A record H1

The 2019 gold repatriation exodus helped push total central bank bullion purchases in the first half to a record $15.7 billion. According to the World Gold Council the 374 tonnes, led by Poland, China and Russia, was the largest gold acquisition ever by public institutions during the first half of a year.

The WGC’s third-quarter report shows more of the same, with year-to-date central bank net purchases (gold buys minus sales) 12% higher than YTD 2018. A total 651 tonnes of gold was accumulated last year, 74% more than 2017 and the highest amount since the end of the gold standard in 1971.

In the third quarter, the most active buyers continued to be Turkey, Russia and China, all of which have good reason to move away from US-dollar assets like Treasuries and into gold, due to bipartisan tensions with the United States.

Between them, Russia and China have diversified over $3 trillion in reserves away from the dollar. This “de-dollarization” trend is something we at AOTH have followed closely. According to an IMF report, the dollar’s share of global foreign currency reserves in Q2 2019 fell for the sixth straight quarter, to the lowest level since 2013. As central banks are dumping dollars, they are buying gold.

Along with the Trump administration’s obsession with trade imbalances and tariffs, Gold Telegraph points out another reason why countries are wanting to bring their gold home from the US:

It’s not a secret that there is a lack of confidence with regards to the U.S. Treasury’s claim that it currently holds 261,000,000 ounces of gold in Fort Knox and other locations. On top of that, the official gold reserves have never gone through a thorough independent audit.

Which you would think makes lots of countries feel quite uneasy with regards to their gold holdings.

Q3 also extended the trend of purchases by a broad spectrum of emerging market central banks; 14 reported adding more than one tonne to their gold reserves this year including the UAE (4.9t), Qatar (3.1t), Kazakhstan (2.1t), Kenya (1.9t) and the Kyrgyz Republic (1.2t).

Turkish gold reserves saw the largest increase in the quarter, 71.4 tonnes, including its largest-ever monthly purchase, 41.8t, in August – pushing the NATO ally’s total reserves to 385.5t, the most on record. In April Turkey apparently withdrew 220 tons of gold held by the US Federal Reserve, valued at $25.3 billion.

Russia’s gold reserves swelled to 2,241.9 tonnes after adding 34.9 tonnes in Q3. It’s interesting to note that the Russian central bank almost halved its US dollar reserves, from 43.7% to 23.6%, as it diversifies into gold and other currencies including the euro and the yuan.

China’s gold reserves rose by a modest 21.8 tonnes during the quarter; the People’s Bank of China has added to its bullion pile every month since it resumed buying gold last December, but in October it hit pause – having accumulated over 100 tonnes in 10 months.

Uzbekistan, Guinea and Mongolia were the only countries to lower their reserves by over a tonne.

In the above-mentioned cases of repatriation, the banks holding other countries’ gold had no problem returning it. Not so when the president of Venezuela, Nicolas Maduro, asked the Bank of England to return Venezuela’s substantial gold reserves to help deal with the country’s economic crisis.

The trouble was, doing that would violate international sanctions against Venezuela’s foreign exchange reserves. The sanctions were an attempt to cut Maduro off from his assets and steer them towards the country’s opposition leader, Juan Guaido, who claimed the presidency.

So in January 2019, the Bank of England refused Maduro’s request to repatriate a billion dollars worth of gold, a significant chunk of its $8 billion in foreign reserves.

Maduro later did an end-run around the sanctions by loading 7.4 tons of gold worth $300 million from its central bank onto Russian planes, which flew to Uganda for liquidating into cash.

A Wall Street Journal investigation revealed how the scheme worked: once the gold arrived at the airport in Entebbe, it would pass through a legitimate gold refinery, which would then sell it to companies in the Middle East.

Maduro’s lucrative black market gold trade allowed him to maintain control of his regime, and keep his military loyal to him, by selling an estimated 73.3 tons of bullion valued at around $3 billion to companies in the Middle East and Turkey between 2017 and February 2019.

Research by Ahead of the Herd also showed how Maduro used gold bullion as collateral for billions of dollars in loans:

The Kremlin loaned the country about $3 billion in 2017, but compared to Venezuela’s $120 billion debt, it’s a drop in the bucket. The New York Times reports Russia lent Venezuela $10 billion from 2013-17, for a price: oil and influence. Last year the biggest oil company in the world, state-owned Rosneft, bought nearly half of Citgo, PdVSA’s refining subsidiary in the United States. The purchase was collateral for a $1.5B loan the Kremlin made to PdVSA.

In the vault

Who owns the most gold and where is it? Considering that central banks account for about one sixth of total gold demand, it’s good to know the answer. Recent figures from the International Monetary Fund and the World Gold Council show the 10 central banks with the most bullion are, in order, the United States, Germany, Italy, France, Russia, China, Switzerland, Japan, Netherlands, and India.

Conspicuous in its absence from this list is the UK, which holds a lot of other countries’ gold but not that much of its own. Although Britain is the fifth largest economy, its 310 tonnes of gold put it 19th on the list of bullion holders. Still, the Bank of England’s 400,000 gold bars are worth over £100 billion by today’s prices; most is 24-karat but older gold may be 22 karat or 900 purity depending on its age and origin.

The Bank of England’s gold haul topped out in the 1950s at 2,543 tonnes, before being cut nearly in half by a major sell-off in 1970, done to protect the pound, Bullion By Post explains. Between 1999 and 2002, then-Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown presided over gold sales that again reduced the gold pile by half, in a highly criticized move.

Since 2010, UK gold reserves have hovered around 310-314 tonnes, a pittance compared to the US with its eye-popping 8,133.5 tonnes, comprising a hefty 74.9% of its foreign exchange reserves.

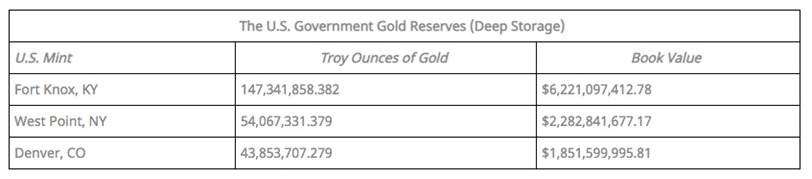

According to the Bureau of the Fiscal Reserve, most of the US gold (147.3 million ounces) is held at Fort Knox, KY in “deep storage” which the Bureau defines as “That portion of the U.S. Government-owned gold bullion reserve which the Mint secures in sealed vaults that are examined annually by the Treasury Department’s Office of the Inspector General and consists primarily of gold bars.”

The balance is held at West Point, NY and Denver, CO. This is the gold owned by the U.S. Mint.

The current breakdown of the amount of gold held in troy ounces at each location and its book value is tabled below. Not included is 13,452,31 oz held by the Federal Reserve Bank in New York.

It’s important to understand that the gold used to make investment-grade coins like American Eagles comes not out of deep storage, but from the US Mint’s working stock, currently sitting at 2,783,218 troy ounces as of Nov. 30, 2019.

The total amount of gold therefore owned by the US Treasury is 261,498,426 oz, of which 258,641,878 oz is gold bullion and 2,857,048 oz is counted as gold coins, blanks and miscellaneous. Total book value is $11,041,059,957 ($11.041 billion).

Impressive as that reads, Bullion Star precious metals analyst Ronan Manly believes there is reason to be skeptical of these widely publicized figures. Manly told RT, a Russian news site, that “The entire story around the US gold reserves is opaque and secretive.” He confirms Gold Telegraph’s statement above that an independent audit of the gold has never been done. “The custodians of the gold, the US Mint and Federal Reserve of New York will not let anyone into the vaults to view or count it.”

Manly also points out that the gold may not be very good quality. According to details that have been provided regarding the US gold reserve, the majority of the gold bars are of low purity and in weights that don’t conform to ‘Good Delivery’ specifications. If true, that means most US gold could not be sold on the open market but rather could only be purchased by central banks wanting to swap their Good Delivery Bars for low purity, non-standard-weight US bars.

ETF funds flowing

In this broad-brush survey of the current gold market, apart from central bank gold repatriation, the other two trends that stand out are gold ETF inflows and gold M&A.

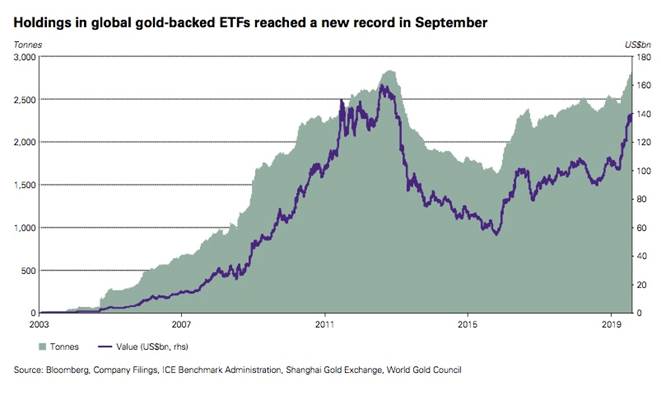

According to the World Gold Council (WGC), in September gold ETF funds grabbed an extra 75 tonnes, with most coming from North America, bringing the total to 2,808 tonnes worldwide – the highest level of all time. ETF holdings expanded for 17 days in a row, as of October 9, which is the longest run of inflows since the financial crisis.

COMEX net longs – bets that bullion will climb higher – reached an all-time high of 1,134 tonnes in September.

Data from the World Gold Council’s third-quarter report shows flows into gold-backed exchange-traded funds are continuing apace. In fact they hit an all-time high of 2,855.3 tonnes in Q3, driven by “accommodative monetary policies, along with safe-haven and momentum buying,” states WGC. Quarterly growth of 258.2t was the most since the first quarter of 2016 when gold finally turned the corner after a multi-year slump.

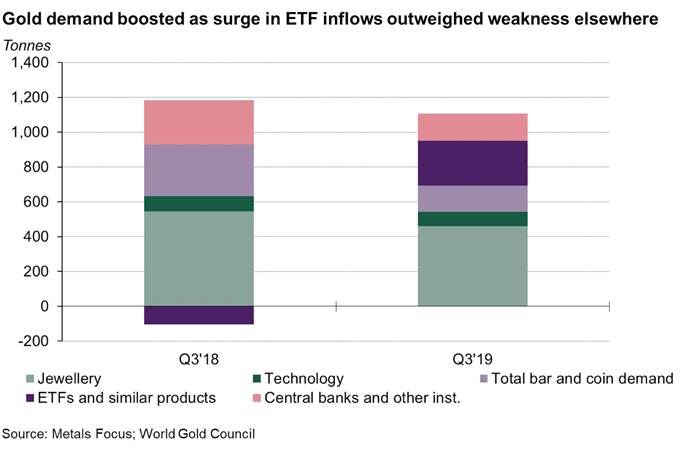

It’s interesting to observe that, even though the third quarter’s ETF buying was lower than the record level reached in third-quarter 2018, it was enough to off-set weakness elsewhere, namely, in jewelry and gold bar/coin demand. Those two sectors saw a 16% and 50% reduction, respectively, owing to rising gold prices which crimped buying. Bar and coin demand fell to an 11-year low.

Spot gold gained 5% during Q3, hitting a high of $1,550/oz on Sept. 4 – a six-year high – before slipping to $1,410 on Sept. 10 and ending the month at $,1490. WGC states:

The rally is partly a reaction of ongoing global monetary policy decisions – most notably, the Federal Reserve (Fed) cutting rates and the European Central Bank announcing that it would resume quantitative easing – but also of continued geopolitical uncertainty, a global economic slowdown, and the level of negative-yielding sovereign debt.

M&A

The financial web pages have been full of stories about gold industry consolidation of late. Indeed gold mining companies look set to extend a deal-making spree that could leave 2010’s record $25.7 billion in mergers and acquisitions in the dust.

So far this year there have been 348 deals worth over $30.5 billion – led by the mega-billion-dollar mergers of Newmont with Goldcorp and Barrick with Randgold.

A run through recent gold mining M&A shows the following transactions:

- Endeavour Mining rejected a $1.9B takeover bid for West Africa-focused Centamin Plc – a 13.1% premium to its Dec. 4 closing share price.

- Zijin Mining Group, China’s largest gold miner, agreed to buy Continental Gold, a junior, and its Buriticá project in Colombia, for $1.3 billion cash.

- Kirkland Lake Gold said it intends to snap up Detour Gold for $4.9 billion.

- Australia’s Saracen Mineral Holdings announced its intention to buy Barrick Gold’s 50% stake in the Super Pit gold mine in Western Australia.

- Kinross Gold is selling its remaining shares in Lundin Gold – a 9.2% stake – to Newcrest Mining of Australia and the Lundin Family Trust, for $113 million.

- Chinese National Gold Group, the country’s second largest gold miner, is reportedly mulling a bid for a stake in Canada’s Iamgold.

- Evolution Mining of Australia has agreed to buy Newmont Goldcorp’s Red Lake gold mining complex for $375 million cash.

Hindsight is 20/20. It appears we were bang-on when earlier this year we predicted a lot more M&A would take place in 2019. At the time I wrote,

Nearly a decade of slumping prices, shareholder revolts demanding CEOs step down after billions in lost market capitalizations, and write-offs of gold mines purchased at the top of the gold price run, all pushed miners to slash debt and lower costs in order to become more efficient. Merging is the next step.

The difference between current consolidations and the mergers and acquisitions of nearly a decade ago is that now, acquirers and their shareholders are far less willing to pay high premiums; they are scared of over-spending and later having to write off billions in assets, like happened during the 2012-16 mining bear market.

Thus we see Barrick paying no premium for South Africa’s Randgold in 2018 and Newmont only offering an 18% premium to Goldcorp’s shares when the two companies merged to create the world’s largest gold miner.

Peak gold, proven

The other important factor to appreciate about the current round of gold M&A is “peak gold”, a topic we have explored in previous articles.

Like peak oil, peak gold refers to the point when gold production is no longer growing, as it has been, by 1.8% a year, for over 100 years. It’s stopped growing because existing mines are getting depleted without enough new gold deposits to replace them.

It’s unsurprising that gold companies are finding it tougher to add to global reserves. The fact is, all of the easy, low-hanging fruit has been picked. Even with a six-fold increase in exploration spending between 2002 and 2012, there has been a significant dearth of new discoveries.

According to McKinsey, in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, the gold industry found at least one +50 Moz gold deposit and at least ten +30Moz deposits. However, since 2000, no deposits of this size have been found, and very few 15Moz deposits.

Any new deposits will cost much more to discover. This is because they are in far-flung or dangerous locations, in orebodies that are technically very challenging, such as deep underground veins or refractory ore, or so far off the beaten path as to require the building of new infrastructure from scratch, at great expense.

The costs of mining this gold may simply be too high.

Kitco reported on findings by BMO Capital Markets that global gold production is expected to drop for the next two years; last year was the second in a row that gold production fell.

Others agree, the main problem is the lack of significant deposits to replace dwindling reserves.

“When we look out over the next five years, there are very few large scale new gold projects earmarked to come on-stream,” the BMO analysts said. “The only large-scale gold projects that we see as probable to enter the top 10 producing gold mining operations by 2025 are the Donlin Creek project, owned by Barrick and Novagold, and Sukoi Log owned by Polyus Gold.”

Another interesting stat: The 10 largest gold mines operating since 2009 will produce 54% of the gold as a decade ago – 226 tonnes versus 419 tonnes.

Many question peak gold but we’ve proven it. Consider the evidence:

In 2018 gold demand reached 4,345.1 tonnes.

WGC reports that 2018 was a record year for mined gold production – 3,347t.

Gold jewelry recycling was 1,173t, bringing total gold supply last year to 4,520t.

If we stop there, we show a slight gold supply surplus of 175 tonnes. Peak gold debunked!

Not so fast, let’s think about those numbers for a minute. In calculating the true picture of gold demand versus supply, we, at Ahead of the Herd don’t, and won’t, count jewelry recycling. What we want to know, and all we really care about, is whether the annual mined supply of gold meets annual demand for gold. It doesn’t! When we strip jewelry recycling from the equation, we get an entirely different result. ie. 4,345 tonnes of demand minus 3,347 tonnes of production leaves a deficit of 998 tonnes.

This is significant, because it’s saying even though major gold miners are high-grading their reserves, mining all the best gold and leaving the rest, even hitting record gold production in 2018, they still didn’t manage to satisfy global demand for the precious metal, not even close. Only by recycling 1,173 tonnes of gold jewelry could gold demand be satisfied.

No wonder, then, that for gold miners to grow, they need to “eat each other”. They require big gold mines, and the only options out there are existing mines run by their competition. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

Junior gold M&A

In the junior resource game we often say that M&A at the top of the mining food chain – the majors doing deals amongst themselves – will trickle down to the mid-tiers and the exploration companies, whose job is to make new discoveries that the larger gold companies are interested in developing further.

This time around, those words carry more weight than usual because we can see it happening. Australian companies in 2018 started to poke around North America looking for good projects. They found two in Alaska’s Pogo underground silver-gold mine, purchased by Northern Star Resources; and Arizona Mining’s Hermosa project featuring a high-grade deposit of zinc manganese and silver, purchased (along with the company) by Western Australia’s South 32 which paid $1.3 billion cash.

In 2019 junior mining M&A continued to roll, with Australians again taking the lead with gold producer St. Barbara snapping up Atlantic Gold for $536 million. Melbourne-based St. Barbara paid an unusually high 39% premium to acquire Atlantic Gold and its Moose River project in Nova Scotia. Australia’s BHP, the globe’s largest miner, can also be counted among the junior M&A tally, with its Nov. 25 decision to invest a further $22 million in Ecuador-focused SolGold, thereby making it the largest shareholder at a 14.7% ownership interest.

In September it was a Canadian firm’s turn to buy into the junior gold space. Osisko Gold Royalties purchased all the shares it didn’t already own in Barkerville Gold Mines for CAD$338 million, giving it access to Barkerville’s Cariboo gold project in British Columbia. Osisko also in September purchased Stornoway Diamond out of bankruptcy protection after the latter halted operations at its Renard 65 mine in Quebec.

Importantly, juniors are seeing more money flowing into the sector – a welcome change after years of slim pickings.

Between 2017 and 2018, bought-deal financings, whereby investment banks buy chunks of shares from juniors – have slumped 40%.

A 2019 report by deal tracker Oreninc and the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) paints a glum picture of our junior resource market, albeit with a few bright spots.

Between 2011 and 2018, nearly half (47.9%) of all junior funds raised were by companies under $100 million market cap (where most juniors lie) whereas companies above $500 million market value raised under 15% of the funds.

It was also noted that of the various commodity types, gold was by far the leader, with 42% of funds raised in 2018, compared to 2.2% for silver and 7.9% for copper.

For example, when Guyana Goldstrike reached out to China’s Zijin Mining looking to fund an exploration program in Guyana, the gold major came through with a substantial $3.2 million – in exchange for a 24% stake.

The funding is through Gold Mountain Assets, which manages Zijin’s Global Fund and its Midas Exploration Fund. The two funds are separate, with one strictly for exploration and the other set up to invest in pre-production opportunities. Guyana Goldstrike received an investment from both funds.

Last week GT Gold shareholders got a lift after Newmont Goldcorp said it would arrange $6.2 million in financing, in exchange for a 14.9% stake in the BC-focused junior.

And then there’s Eric Sprott. The Canadian billionaire investor and gold-backed ETF pioneer has reportedly spent over CAD$139 million on 17 gold and silver explorers and some nickel juniors since May. The recipients include Ely Gold Royalties, Silver One Resources, Chesapeake Gold and Discovery Metals.

When Eric Sprott splashes the cash, it’s time to pay attention.

Conclusion

Gold is the only store of value that can be counted on in a time of crisis when everything else – ie. fiat money – fails.

As we discussed in Gold and a gun, there are many extreme events that could do massive damage to planet Earth within hours, even seconds. They are in addition to a potential financial calamity that follows Brexit, or another Great Recession.

Having gold coins may be the only thing that separates you from the 99% of the population that will rely on the charity of others to make it through a “Carrington Event” like a solar EMP or a complete melt-down of the monetary system.

Apart from having some physical gold we here at AOTH also believe we need to own a few gold stocks. Right now we’re seeing the gold industry consolidate. It’s very encouraging to see M&A among the largest gold companies starting to trickle down to mid-tiers like Osisko Gold Royalties and St. Barbara, and several juniors. It’s also heartening to witness investment dollars starting to flow back to the juniors. It’s about time.

For all of these reasons I am very optimistic about the precious metal and the companies that explore for and mine it, as we head into the next decade.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions.

Richard Mills owns shares of Guyana Goldstrike (TSX.V:GYA). GYA is an advertiser on his site.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.