Resource nationalism, production cuts denting copper supply

2019.05.25

2018 was an aberration of the copper market in that there were no major strikes or natural disasters to significantly reduce supply of the red metal and hike prices.

Usually labor disruptions can be counted on to de-rail the pessimistic predictions of analysts who often forecast an oversupplied copper market – particularly in Chile and Peru – the top two producing countries, both prone to worker unrest. But last year was an exception.

At Escondida, one of the world’s largest copper mines, the 2,500-strong union approved a new deal last summer that averted a repeat of the 43-day shutdown in 2017 which cost the owners, BHP, Rio Tinto and two Japanese consortiums, around $800 million in lost production.

This year the market looks to be back on trend, however. Workers are poised to down tools at Chile’s Chuquicamata mine, a massive open-pit operation run by Chilean state copper mine Codelco.

The world’s largest copper company on Friday presented its final offer to three unions as the parties remain deadlocked in contract negotiations. Reuters reports union heads already rejected a $19,700 bonus per worker and a 1.2% raise.

Employees have said they will strike if the state-owned copper producer does not meet their demands; a vote is slated for May 28-29.

Work stoppages aren’t the only factor that could lift the copper price this year. Governments in two major copper producers in Africa – Zambia and the DRC – are each trying to grab a bigger slice of their country’s copper pie – thereby setting the global market up for another supply squeeze if copper miners in those countries decide to shrink output in the face of rising costs.

The mainstream media is blaming the trade war as the main antecedent behind copper’s current weakness. It is certainly a factor, but there is a lot more going on. In this article we get granular over copper supply, with the overall conclusion pointing to a bullish future for the base metal, widely used in construction, telecommunications and transportation.

Price factors

What moves copper prices? Materials Risk cites 10 factors. The usual suspects include, as already mentioned, strikes and weather, which can slow or halt mine production; economic growth usually measured globally or in China, the world’s number 1 copper consumer; copper stock levels, the amount of copper stored in warehouses; and various demand factors such as the health of the building industry in China, the potential for infrastructure build-outs requiring a lot of copper, and most recently, the continuing growth in electric vehicles which take four times as much copper as a gas-powered car.

The US dollar also needs to be considered. Because copper is priced in US dollars, a rise in the dollar means it takes more of a weaker currency to buy copper priced in dollars, which dents demand. A weak dollar can also serve as a disincentive for producers in other countries (eg. Chile), since a cheaper greenback buys less pesos needed to pay costs, and therefore squeezes profit margins.

Oil prices factor in too. It is estimated that energy costs represent about 30% of copper refining prices. There’s also the availability of copper scrap, since a large amount of copper is recycled; the Strategic Reserves Bureau which in China manages the country’s copper stockpiles; Chinese collateral demand, wherein companies purchase copper as collateral to secure loans; speculation, where hedge funds and other large financial institutions place bets on where the future copper price is heading; and finally, copper refining activity.

This is important because mined copper must be refined before it can be sold. A smelter’s treatment and refining costs usually rise when there is a large supply of copper, since copper miners demand more refining capacity.

Temporary weakness

There is no getting around the fact that the copper market is experiencing some weakness. However, we see the current price slippage as a blip in what the evidence points to as a growing and powerful bull market for copper.

What is happening right now in the copper market to push down prices? It basically comes down to Chile, the largest producer, and China, the biggest consumer. A high US dollar and recent stronger oil prices have also weighed on copper.

For Chile, strong copper prices spread ripples across the entire Chilean economy since it is by far the largest export commodity. Conversely, weaker copper prices cast a pall over the economy. Seeking Alpha reportsthat monthly activity levels, industrial production and consumer confidence in Chile have all been weaker than expected. At the same time, the Chilean peso has fallen against the US dollar; as explained above, a high dollar usually beats down copper prices.

The Chinese economy, which hummed along at near double digits for a decade, is currently experiencing weakness at about 6% growth. But the country still requires massive amounts of copper to refine and ship to building sites, factories and assembly plants. And 6% is still pretty good, isn’t it? In a recent article, Reuters examined why iron ore prices have gained more than copper this year, even though both are heavily-demanded industrial metals.

It found that the answer lies in the Chinese construction industry. Whereas steel, produced from iron ore and coal, is needed at the beginning of the construction cycle, copper in the form of wiring and piping is used at the end. Right now, housing starts are booming in China, but property completions are lagging behind. That means less copper and other base metals like aluminum, are needed.

But this situation is expected to be temporary. Quoting from the article, “The yawning gap between property starts and completions implies that at some stage copper usage in China’s construction sector will rise as completions start catching up with starts.

“Analysts such as Citi are looking for this to happen some time in the second half of 2019, meaning a pending demand boost for copper.”

In other words, look for a copper price correction sometime in the second half of the year. In the meantime, while the copper market is still nervous over the China-US trade deadlock, there was a positive signal on Friday.

The two main stock market indices – the Dow and the S&P 500 – ticked higher on comments from Donald Trump saying that he sees a resolution to the trade war “happening fast”.

Q1 output plunge

Everybody looks at the price of copper over the past little while and screams “trade war!” when they should be yelling “supply danger!”

Earlier this year at MMG’s Las Bambas mine in Peru, protesters blockaded a public road, disrupting copper concentrate from leaving the site. While productions levels weren’t impacted, the transportation of personnel and supplies were.

“The dispute at the Las Bambas mine is preoccupying some quarters, given that this is already a year where mine supply looks set to post its second decline in two years,” Karen Norton, senior analyst at Refinitiv, formerly Thomson Reuters Financial and Risk, told INN at the time. In Chile, copper and lithium mining were affected in January and February by heavy rains.

Exports from Indonesia’s Escondida, the world’s second largest copper mine, are expected to drop this year by 85% due to operations moving from open-pit to underground. That’s a dramatic fall from 1.8 million tonnes in 2018 to just 200,000 in 2019. The mine is expected to take until 2022 to re-gain full production, I find it hard to believe they will produce the same tonnage from underground as open pit.

Globally, MINING.com reported a 2.4% production fall in February, with Chile and Peru hit the hardest, at a respective 7.1% and 5.1% reduction, year on year.

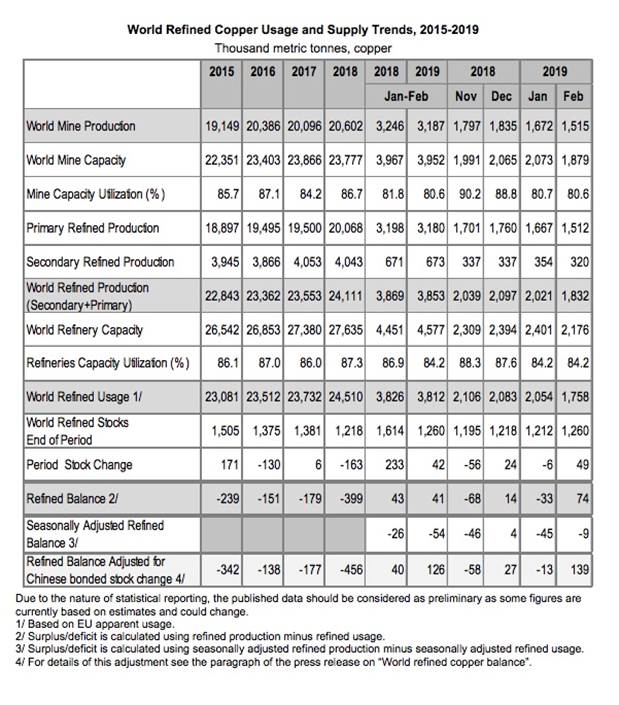

In fact a look at first-quarter global production levels, courtesy of the International Copper Study Group, finds quite a serious drop. World copper mine production has shrunk from 1.797 million tonnes in November 2018, to 1.515Mt in February 2019, an 18.6% decrease.

Zeroing in on the first two months of the year, ICSG explains what’s happening:

“Although a few countries experienced growth, this was largely offset by declines in two major producing countries, namely Chile and Indonesia. Production in Chile, the world’s biggest copper mine producing country, declined by 6% mainly due to lower copper head grades. Indonesian concentrate production declined by 50% primarily as a consequence of the transition of the country’s major two mines to different ore zones leading to temporarily reduced output levels.”

Declines in mined copper throughout the first quarter appear to be showing up in London Metal Exchange (LME) warehouse levels. A 30-day chart shows warehouse levels rising in the last week of April to 232,225 tonnes, then falling sharply to the current 186,475t – a significant reduction of 24%.

African tax grabs

While resource nationalism is among the worst things a mining company can encounter when investing in a foreign country (just ask Crystallex which fought Venezuela for years over a 2008 decision to expropriate its Las Cristinas gold project, finally winning a $1 billion settlement), it can also have an impact on metals fundamentals. If enough supply is taken out of the market due to government-imposed restrictions, prices of those metals will rise.

For example Indonesia’s 2014 ban on unprocessed ore exports helped support nickel and bauxite prices, which also tumbled when the ban was relaxed in 2017. In the Philippines, the government of hard-line President Rodrigo Duterte closed 23 mines in 2017, causing the nickel price to climb. Like Indonesia, the southeast Asian nation blocked the export of unprocessed minerals – preferring to process locally – but went further by banning mining in watersheds and forcing companies to seek legislative approval before operating.

The latest round of resource nationalism appears to be occurring in Africa.

In Zambia, an economic crisis is forcing the country to consider seizing copper mines, according to a recent story in Bloomberg. The news site reported that the yields on Zambia’s Eurobonds hit record highs (only basket case Venezuela’s yields are higher) after the Zambian government said it plans to seize Vedanta Resources’ assets.

The government wants to liquidate Vedanta’s Konkola Copper Mines (KCM) which it accuses of breaching its operating license and polluting the lands of nearly 2,000 villagers, Reuters said. A court hearing in England is pending.

For its part, Vedanta claims it is owed nearly $180 million in value-added tax refunds.

Zambia, Africa’s second largest copper producer, is expecting copper production this year to be up to 100,000 tonnes less than in 2018.

Zambia’s Chamber of Mines attributes the production drop to changes in mining taxes which have driven up costs and forced copper miners to reduce output. The country’s copper production has already tumbled 11.3% in the first quarter of 2019 versus the last quarter of 2018.

Meanwhile First Quantum Minerals, which is offering to buy the Zambian government’s 20% stake in the country’s largest copper mine, Kansanshi, giving the company 100% control, is also fighting with the government over a $7.9 billion tax bill. The 1.5% increase in mining royalties this year prompted First Quantum to announce plans to fire 2,500 workers, but it later backtracked on the proposal, according to the Financial Post.

Last year the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) also raised taxes and royalties on copper and cobalt – of which the DRC is the number one producer – amid fierce opposition from miners.

Long-term supply deficit

As we wrote in The coming copper crunch, copper mine production is expected to increase for the next year or so, then drop off significantly. (But as we showed in the section on Q1 above, global copper production is already down, between November and February, by 282,000 tonnes).

Codelco has said it produced less copper in 2018 versus 2017, owing to declining ore grades at its aging mines. We’re talking a 3.3% drop, from 1.8 million tonnes to 1.6 million tonnes, resulting in $0.8 billion less profit, before taxes.

In case that isn’t convincing enough to indicate a serious problem with copper supply, we consulted two often-referenced international bodies, the International Copper Study Group (ICSG) and London-based research firm CRU.

ICSG notes, as I mentioned at the start of this article, that 2018 was unusual for the lack of supply disruptions in the copper market. The organization further notes that besides the restart of the Katanga mine in the DRC, no major new copper mines were brought online last year.

2019 is also expected to see supplies tighten. In its latest press release, ICSG states:

In 2019, additional output from the start-up of the major Cobre de Panama mine, the expansion of Toquepala mine and the commissioning of a few small/medium mines is expected to be balanced by a significant decline in Indonesian output (due to the transition of Grasberg to an underground operation and Batu Hijau mine to phase 7) and regulatory/taxation issues which will negatively impact output in Zambia.

Regarding refined copper, ICSG sees world refined copper production to increase 1.2%, but this will be offset by global refined copper consumption which is expected to rise 2% in 2019 and 1.5% in 2020. The result is a deficit of around 190,000 tonnes in 2019 – triple the 65,000t deficit ICSG predicted at its October, 2018 meeting – and about 250,000t in 2020, ICSG concludes.

CRU isn’t quite so bullish, but it still forecasts a copper market deficit for the early 2020s – albeit not as large as previously thought, owing to recent expansions such as Anglo American’s Quellaveco project and Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca mine.

Conclusion

The current weakness in the copper price, owing to the US-China, trade war, is a temporary phenomenon. Smart investors follow long-term trends and are unconcerned with temporary setbacks.

After writing this article, it’s clear to me that we are on the cusp of a major change in the copper market, where supply is not going to be able to keep up with demand. A deficit is expected. If supply can’t meet demand that means one thing: higher prices. It also means that governments (and companies) will be scrambling to get their hands-on new copper properties to meet the demand. Nothing less than their economic growth is at stake. Without copper, construction and the automotive industries would grind to a halt. Maintaining a smooth supply chain is critical to growth.

Demand for the red metal needed for construction, communications and transportation, is now being wired in, pun intended, to the tectonic shift of the global transportation system, from reliance on the internal combustion engine to electric vehicles. Copper is an essential component of EVs, using four times as much copper as regular cars. That means copper demand is going to soar even higher than it already is.

Unless new investments arise to meet copper demand in the 2020s – driven much higher due to the need for copper in electrical vehicles and renewable energy applications, along with major infrastructure spends such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative – the world is going to be scrambling for the essential base metal.

By 2035, without major new mines up and running to replace the ore that is being depleted from existing copper mines, we are looking at a 15-million-tonne supply deficit. Four to six million tonnes of added capacity are needed by 2025.

Copper grades have declined about 25% in number one producer Chile in the last decade – highlighting the urgent need for grassroots exploration to arrest the trend.

Due to the waning supply we can already see happening, now is the time to pick out a few companies to ride the coming copper bull.

The question is, which companies and where? At AOTH, we have identified four copper juniors with excellent projects mining-friendly jurisdictions. Check out my front page to learn more.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.