Resource nationalism could further choke metal supplies

2019.02.22

Three of the most important metals surged on Wednesday due to a signal from the US President that he may not escalate the trade war with China.

Gold hit a 10-month high just shy of $1,350 an ounce, copper was the highest it’s been for seven month, trading at $2.92 a pound, and iron ore extended earlier gains at $88 a tonne.

Trump reportedly said he could extend the March 1 deadline for raising US tariffs on Chinese imports if the two sides are making good progress on reaching a deal on the nearly one-year-old dispute.

“I can’t tell you exactly about timing,” BBC News quoted the President saying, when asked how likely it would be for the US to increase the duty on $200 billion worth of Chinese products from 10% to 25%.

“The date is not a magical date because a lot of things are happening,” he added, presumably referring to trade talks in Washington this week.

The China-US trade war started with import duties on aluminum and steel. Justifying the tariffs on national security grounds, the 25% tax on steel and 10% on aluminum were aimed at China for dumping cheap product into the States, thus lowering the prices of those metals and hurting American steel and aluminum producers.

While China was the obvious target, the steel and aluminum tariffs also wrapped in the EU, Mexico and Canada.

Tariffs are a blunt instrument in the toolbox of protectionist measures all countries have when negotiating trade agreements. There are other, more subtle ways of protecting local industries and keeping foreign companies out or at bay. In the mining business we call this resource nationalism. It has been a prevailing theme especially over the last few years as countries experience wider inequality, social unrest and often unsustainable levels of debt. Tapping a wealthy foreign mining company for more profits, or just expropriating the mine and kicking the company out, is often seen as the easiest way to fix a cash crunch, while at the same time appealing to nationalist sentiment.

As we know, nationalism and “populism” have become more and more prevalent – the election of Trump in 2016 being the ultimate expression of populism, despite Trump, the billionaire real estate tycoon, being the antithesis of the “everyman (or woman)” most populists go for.

While resource nationalism is among the worst things a mining company can encounter when investing in a foreign country (just ask Crystallex which fought Venezuela for years over a 2008 decision to expropriate its Las Cristinas gold project, finally winning a $1 billion settlement), it can also have an impact on metals fundamentals. If enough supply is taken out of the market due to government-imposed restrictions, prices of those metals will rise.

For example Indonesia’s 2014 ban on unprocessed ore exports helped support nickel and bauxite prices, which also tumbled when the ban was relaxed in 2017. In the Philippines, the government of hard-line President Rodrigo Duterte closed 23 mines in 2017, causing the nickel price to climb. Like Indonesia, the southeast Asian nation blocked the export of unprocessed minerals – preferring to process locally – but went further by banning mining in watersheds and forcing companies to seek legislative approval before operating.

Philippines is the world’s top nickel ore supplier but mining contributes less than 1% to GDP, prompting Duterte to go after mining companies for not paying enough taxes, especially those that cause environmental damage.

This article will take a deep dive into resource nationalism and how recent examples of state-imposed strong-arming could exacerbate already tight supplies of gold, copper and zinc, and potentially impact rare earths and lithium. But first, a primer on resource nationalism. What is it exactly?

Country risk + security of supply = resource nationalism

Access to raw materials at competitive prices has become essential to the functioning of all industrialized economies. As we move forward, developing and developed countries will, with their massive population booms and necessary upgrades of worn-out infrastructure, continue to place extraordinary demands on their ability to access and distribute the planet’s natural resources.

Threats to the access and distribution of these commodities include:

- Political instability of supplier countries

- The manipulation of supplies

- The competition over supplies

- Attacks on supply infrastructure

- Accidents and natural disasters

- Climate change

Accessing a sustainable, secure, supply of raw materials is a number one priority for all countries. Increasingly we are seeing countries ensuring their own industries have first rights of access to internally produced commodities and looking for such privileged access from other countries.

Numerous countries are taking steps to safeguard their own supply by:

- Stopping or slowing the export of natural resources

- Shutting down traditional supply markets

- Buying companies for their deposits

- Project finance tied to off-take agreements

Resource nationalism is the tendency of people and governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over natural resources located on their territory.

Traditionally the major benefits for developing countries (from their natural resource endowment) have come in the form of:

- Employment/wages

- Government revenues – taxes, royalties or dividends

There can also be indirect benefits such as knowledge and technology transfers. Foreign investments can involve infrastructure spending, sometimes on a massive scale, like electricity, water supplies, roads, railways, bridges and ports.

Today many governments are looking at other ways to get more money from miners.

Ernst & Young says governments have gone beyond taxation in getting more out of the mining sector with a wave of requirements such as mandated beneficiation/export levies and limits on foreign ownership.

- Mandated beneficiation/export levies – Governments are imposing steep new export levies on unrefined ores to force mining companies into domestic ore processing. Minerals processed in-country capture more of the value chain as the products achieve higher prices.

- Increasing state ownership – Miners are easy targets because mining is a long-term investment and one that is especially capital intensive – mines are also immobile, so miners are at the mercy of the countries in which they operate. Outright seizure of assets happens using the twin excuses of historical injustice and environmental or contractual misdeeds. There is no compensation offered and no recourse.

Gold

The mined supply of gold is shrinking as most of the “low-hanging fruit” has been mined and the rest is either in remote locations or buried deep in the earth, meaning higher extraction costs.

2016 was the first year that mine production fell since 2008. In spring 2018 the World Gold Council in its annual gold trends report said that total gold supply slipped in 2017 to 4,398 tonnes – a drop of 4% from 2016. Mine production was about the same as last year, 3,268.7 tonnes, but recycled gold fell 10% to 1,160 tonnes. Key gold producers that saw drops in 2017 were China and Tanzania.

Tanzania is a country to watch as far as resource nationalism goes – although in this case, the company being targeted has only itself to blame.

In 2017 the government of the East African country banned the export of unprocessed minerals after Acacia Mining, a subsidiary of Barrick Gold, was discovered trying to export copper and gold concentrates valued at over 10 times the amount declared. Acacia was later hit with a $190 billion tax bill.

The company of which Barrick holds a 63% stake, has also been charged with money laundering and corruption. The two parties just settled the dispute with measures that include a $300 million payment to resolve tax claims.

For Barrick it was no small matter. Acacia accounts for roughly 10% of the gold mining giant’s production.

Tanzania also raised royalty rates, published local content regulations stipulating that mining companies must allow for an ‘indigenous Tanzanian company’ to have at least 5% ownership of a project before it is eligible for new mining licences, Mining Weekly reported.

South Africa was once the leading gold producing country but it has since slipped to eighth spot in the world, as the country’s mines get depleted and production costs mount, with companies forced to mine deeper. South Africa’s Mponeng mine is the deepest in the world, at 2.5 miles underground.

Strikes often disrupt supply but global miners in South Africa face another bogeyman: the threat of mines nationalization. A hot topic among the youth wing of the African National Congress back in 2010-11, nationalization is high on the agenda of the radical leftist party, Economic Freedom Fighters.

In its recently released party manifesto, the EEF says it will nationalize all mines by 2023 if elected this year, along with banks and other strategic sectors of the economy. The party would also expropriate land without compensation.

Copper

As we wrote in The coming copper crunch, by 2035, without major new mines up and running to replace the ore that is being depleted from existing copper mines, we are looking at a 15-million-tonne supply deficit by 2035. Four to six million tonnes of added capacity are needed by 2025.

Copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile in the last decade – highlighting the urgent need for grassroots exploration to arrest the trend.

Finally, some of the world’s largest copper mines are slashing production, thus feeding into the supply deficit thesis that is predicted to push the copper price back up over three dollars a pound.

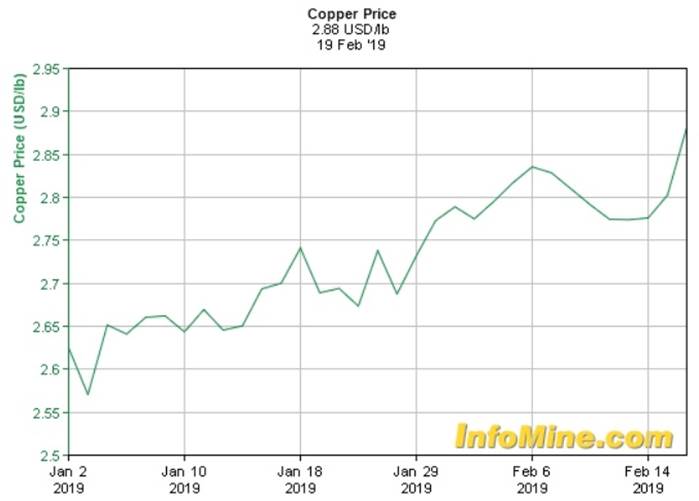

Since the start of the year, copper has risen 10%.

Along with strikes and bad weather that cause “force majeure” (temporary halting of operations), resource nationalism is another factor affecting the copper market. Take the DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo), Africa’s biggest copper producer.

Last year DRC President Joseph Kabila signed a law amending the 2002 Mining Code. The new code increased gold and copper royalties by a respective 1% and 1.5%, and designated cobalt – of which DRC is the world’s leading supplier – a strategic metal. Royalties on cobalt production were hiked by a factor of five, from 2% to 10%.

Africa’s second biggest copper producer, Zambia, has also been pressing the resource nationalism button. An attempt in 2015 to increase royalties backfired when companies warned of mine closure and thousands of lost jobs. A more strategic approach has been to audit mining companies in order to extract more tax revenue. First Quantum Minerals, which through a subsidiary owns and operates Kansanshi, Africa’s largest copper mine, received a bill for $7.9 billion. Mining companies are also being made to transport 30% of their exports by rail, in order to use local railways which have poor infrastructure.

Effective Jan. 1, royalties increased by 1.5% across the board, and will rise to 10% if the copper price goes above $7,500 a tonne, Bloomberg said.

Over in southeast Asia, the countries to watch are Indonesia and Papua New Guinea (PNG), along with the Philippines with its erratic President Duterte. The autonomous region of Bougainville hosts the Panguna mine, one of the world’s largest open-pit copper operations before a 1989 civil war closed it down.

Panguna once accounted for 44% of Papua New Guinea’s GDP.

Changes to Bougainville’s mining act that would have allowed a new company to restart the mine were recently rejected in a vote, MINING.com reported.

In Indonesia, control of Grasberg, the world’s second largest copper mine, changed last September when Freeport McMoRan and Rio Tinto agreed to transfer majority ownership to state-owned mining PT Indonesia Asahn Aluminum (Inalum). Freeport had been fighting for years with the Indonesian government over control of the mine. In 2017 Grasberg operations were halted for over a month due to a ban on concentrate exports, which together with a strike at BHP’s Escondida mine in Chile, helped copper prices rise.

Now the Grasberg mine is facing uncertainty over its export permit which expired on Feb. 15. According to Reuters, PT Freeport Indonesia, a unit of US-based Freeport McMoRan, has not yet obtained a new permit, and for the time being is shipping its concentrate to a local smelter. Indonesia is also forecasting a precipitous drop in copper concentrate exports, from 1.2 million tonnes in 2018 to just 200,000 tonnes this year.

Zinc

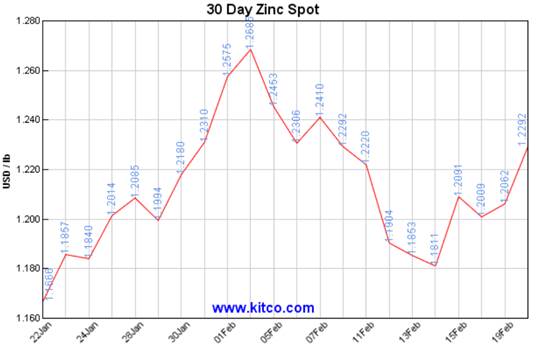

The International Lead and Zinc Study Group predicts the zinc market will be in a deficit position of 72,000 tonnes in 2019.

BMI Research noted in June 2018 that refiners, particularly in China, will have a hard time securing zinc concentrate, due to zinc mine production curtailments in 2015-16 (eg. Rampura Aguchain India, Antamin and Iscaycruz in Peru as well as by Glencore and Nyrstar). For example tightened environmental standards to deal with choking air pollution meant that Zijin Mining cut 8.2% of its zinc production in 2017.

Chinese smelters rely heavily on imported zinc ore. In 2017 China’s refined zinc production was at its lowest in two years due to problems acquiring zinc concentrate.

For more read our Plunging zinc inventories have zinc bulls ready to run

Will the supply materialize? Two of the three largest zinc mines are in Peru, and another top 10 zinc mine is in Bolivia, where President Evo Morales has shown propensity towards radical anti-resource extraction moves like nationalizing the natural gas industry in 2006. While Peru recently elected a more pro-mining government, the country is impoverished compared to its Latin American peers and always prone to anti-mining forces. The Toronto Star reminds us that former Cajamarca governor Gregoria Santos marched alongside protesters that opposed projects, and that “Development plans worth billions of dollars remained stalled in several regions due to local opposition.”

Rare earths

In 2009 the Chinese government placed quotas on its rare earths, resulting in a 40% drop in exports. Beijing said it had to implement quotas to protect the environment from rare earth mining waste, but critics saw them as naked protectionism.

A year later, an international incident sent rare earth oxide prices into the stratosphere. In September 2010 a Japanese naval vessel interdicted a Chinese fishing boat near the Senkaku Islands, which Japan and China both claim ownership of, and detained the captain. The Chinese decided to ban all rare earth exports to Japan, then an industrial powerhouse and China’s largest REE customer. The rare earths market panicked, and within months, all of the rare earth oxides gained in price.

For more read our How the US lost the plot on rare earths

With China controlling 95% of the rare earths market, either through mining or processing, the country is in a unique position to influence oxide prices of the 17 elements in the periodic table, used in a bevy of industrial and military applications.

In October we got a reminder of that, when the Chinese government announced it was cutting rare earth separation and smelting by 36% for the second half of 2018. Manufacturers reportedly were scouring the globe for alternative supplies, with the threat of price hikes looming.

The only other non-Chinese rare earths processor is also facing uncertainty. Lynas Corp’s facility in Malaysia was informed in November that it would need to undergo an environmental review by the newly elected government. The six-year-old plant faced intense opposition from locals before it opened over concerns about how it would handle radioactive waste.

Lithium

The “lithium triangle” straddling Bolivia, Chile and Argentina contains three-quarters of the world’s lithium reserves. Chile is currently the second largest producer of the main ingredient of lithium-ion batteries installed in electric vehicles, behind only Australia, home to the Greenbushes hard rock lithium and tantalum mine owned by Talison Lithium. Argentina mines just under half of Chile’s lithium volume.

While Chile will undoubtedly play a major role in shipping lithium carbonate and hydroxide to electric vehicle battery makers – for the time being anyway, the center of the world’s lithium production has hit a roadblock.

SQM and US-based Albemarle share the same salar (brine lithium deposit), the sprawling Salar de Atacama. The number one and two lithium giants for years have blamed each other for over-exploiting their water rights in the Atacama, where they operate just 12 miles apart.

The Chilean government, fearing a water shortage, has slapped restrictions on water use in the salar.

We know that higher production of Chilean lithium won’t be coming from Albemarle, which also runs the only lithium mine in the United States, Silver Peak in Nevada. In October, the Chilean government said Albemarle failed to live up to a 2016 contract. The country’s nuclear regulator then refused to increase the company’s lithium production quota. Adding insult to injury, Chile’s environmental authority turned down a license it needed to build a US$584 million processing plant – effectively hamstringing the company’s expansion plans.

With the government restricting lithium production, Chile’s position as a major lithium producer appears to be in doubt.

China doesn’t produce much lithium, about 3,000 tonnes compared to Australia’s 18,700 and Chile’s 14,100; the United States has just one lithium brine operation, the Silver Peak Mine in Nevada, but it’s been operating since the 1960s and its grades are said to be declining.

Australia’s current and future lithium mines all have offtake agreements assigned.

This is setting the lithium market up for a possible supply crunch in the coming years, if ever-increasing demand for lithium used in electric batteries and consumer electronics outpaces output. We know that supply from new mines failed to reach expectations from 2012 to 2016; the major lithium miners despite their best efforts to double production in four years, were unable to do so. We also know that Chile is using all the government levers it can pull to keep a cap on what it considers to be a strategic national resource.

In neighboring Argentina, mining companies are reluctant to invest despite pro-business President Mauricio Macri being elected in 2015 – overturning 12 years of leftist rule during which the government imposed a 5% tax on mining exports and banned foreign companies from sending profits home.

In September 2018 Macri’s government imposed a 12% export tax amid economic turmoil, including a 90% devaluation of the peso against the US dollar in six months.

Given that the United States is 70% reliant on lithium imports, can North American electric vehicle battery manufacturers and automakers really depend on Chile and Argentina for their lithium?

Conclusion

Country risk is always an unknown quantity that is difficult to quantify for investors looking to take a position in a junior mining company. We have shown that resource nationalism in all its forms can be a real headache for global or country-specific miners; of course we need to acknowledge that mining companies also have a responsibility for upholding local laws including environmental regulations and labor rights.

Working closely with the host government can ensure a stable, predictable flow of metal and shareholder returns. Failing to meet their expectations can bring on a tsunami of problems that could seriously impair or bankrupt a company. There are numerous historical examples of the latter.

We’ve also seen examples where government-mandated restrictions have moved metals markets – such as when China imposed restrictions on rare earth exports, leading to a spike in rare earth oxide prices; when the Philippines closed nickel mines, hiking the nickel price; and when Indonesia’s ban on concentrate exports helped support the copper price.

Resource nationalism is the black swan that nobody sees coming, but a knowledge of past actions will go a long way towards predicting might happen in the future, thereby guiding investment decisions.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd is on Twitter

Ahead of the Herd is now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd is now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.