Max Resources has found its El Dorado

2019.02.01

In the 1500’s, Spanish explorers set foot on a strange new land, drawn to its shores with a single, focused mission: find the gold.

While many a conquistador set out on fruitless treks into the jungles and mountains of South America, it was the Viceroyalty of New Grenada, as Colombia was then known, that held the most allure. A lost city of gold named El Dorado was waiting to be found, its king so rich that he covered himself in gold dust every day and washed it off in a sacred lake at night.

Five hundred years later, we know there was some truth to the myth. As BBC Magazine explains it, the myth of El Dorado was about people, not a place. Piecing the story together from early texts and archeological research, historians believe that El Dorado was in fact a rite of passage performed by the Muisca people who have lived in Central Colombia since AD800. One of the best accounts is from Spanish chronicler Juan Rodriguez Freyle, written in the 16th century:

In Freyle’s book, The Conquest and Discovery of the New Kingdom of Granada, published in 1636, he tells us that when a leader died within Muisca society the process of succession for the chosen “golden one” would unfold. The selected new leader of the community, commonly the nephew of the previous chief, would go through a long initiation process culminating in the final act of paddling out on a raft onto a sacred lake, such as Lake Guatavita in Central Colombia.

Surrounded by the four highest priests adorned with feathers, gold crowns and body ornaments, the leader, naked but for a covering of gold dust, would set out to make an offering of gold objects, emeralds and other precious objects to the gods by throwing them into the lake.

The shores of the circular lake were filled with richly adorned spectators playing musical instruments and burning fires that almost blocked out the daylight from this crucible-like lake basin. The raft itself had four burning fires on it throwing up plumes of incense into the sky. When at the very centre of the lake, the priest would raise a flag to draw silence from the crowd. This moment would mark the point at which the crowds would commit allegiance to their new leader by shouting their approval from the lakeshore.

Visitors to Colombia can see the mysterious Muisca raft at the Museo del Oro in Bogotá. The spectacular votive offering was made of over 80% gold with an alloy of native silver and copper, sometime between 1,200 and 1,500 BC.

While the Spanish never found their El Dorado, their presence in New Granada did serve to develop and modernize the country. By the 19th century Colombia, named after Christopher Columbus who ironically never set foot there, had become the world’s second largest gold producer.

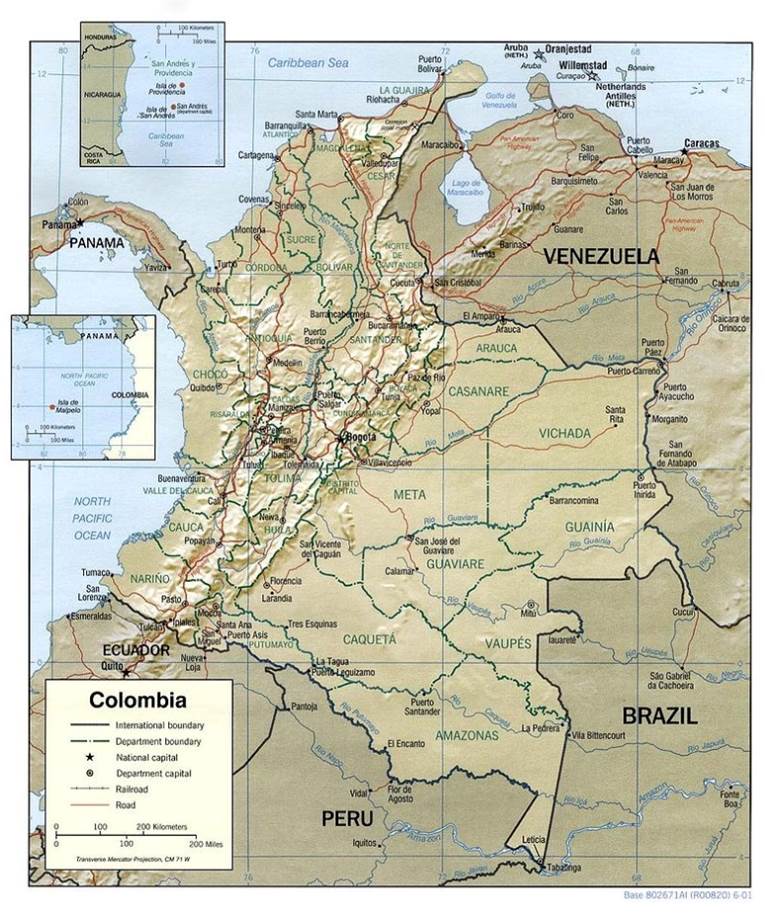

The precious metal is mainly found in three areas: the Andean region, the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta Mountain in the north, and the Guyana Shield.

The Andean is divided into three Cordilleras (Central, Occidental and Oriental, in Spanish). A lot of early Colombian gold was mined in the Central Occidental, located in the department of Antioquia. It is here that four mineral belts run north-northeast: the Choco belt, Middle Cauca belt, Segovia belt and California-Angostura district.

Colombia continues to be one of Latin America’s largest gold producers, mining 1.3 million ounces in 2017. The only countries ahead of it were, in order of volume, Peru, Guyana, Brazil and Argentina.

Gran Colombia Gold is the country’s largest gold and silver producer, with 218,00 ounces mined from its underground Segovia and Marmato operations in 2018. Major gold companies AngloGold Ashanti and Newmont Mining are active in Colombia. AngloGold made two discoveries, La Colosa and Gramalote, since starting exploration in 2012; and Newmont purchased a 19.9% share of Continental Gold in 2017, to develop the Buriticá gold project. Denver-based Newmont, who recently said Colombia is the new Peru, also recently bought into Orosur Mining, to explore the Canadian gold junior’s Anzá project in Antioquia.

Max Resource Corp.

While most people are familiar with the story of El Dorado, it was a fascination with Colombia’s platinum mining history that inspired management at Max Resource Corp. (TSX-V: MXR) to become the next big thing in Colombian gold.

The company has its origins through Bill Hayden, the co-founder of Ivanhoe Mines (and a current Ivanhoe director). Hayden became interested in the potential of the Choco region, which was the largest platinum producer up to World War Two.

When the opportunity came up to acquire a large prospective land package thought to contain precious metals, he put the ball in motion.

Australia’s Noble Metals was looking at spinning its 105,975-hectare property near Medellin into a Toronto-listed company. Last April Hayden met with Brett Matich, a mechanical engineer with a 25-year mining career, to discuss the possibility of a deal – drawing on their considerable industry experience.

Hayden is a veteran geologist with 38 years in mining including 20 years working in Colombia. He led the discovery of Ivanhoe’s (TSX: IVN) Platreef in South Africa – the world’s lowest-cost platinum mine – and also convinced Robert Friedland, Ivanhoe’s other founder and its current chairman, to pivot towards the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where Ivanhoe made the Kamala discovery, one of the richest copper finds on the planet (1.7 billion tonnes at 2.5% Cu).

As CEO of ASX-listed Aztec Resources, Matich oversaw development of the Koolan DSO hematite deposit – vaulting AZR from a A$1 million market capitalization to a $300 million merger with Mount Gibson Iron. Matich also reactivated the Karratha nickel-copper mining operation within just two years as chief executive of Fox Resources, and developed an un-drilled magnetite prospect in Canada into an 8-billion-ton compliant resource, while with Cap-Ex Ventures(TSX-V: CEV)

Last year Max Resource signed a letter of intent with Noble Metals. The letter featured exploration rights to the 105,975 hectares mentioned above, plus a 30-man, purpose-built exploration camp containing pilot bulk testing equipment. This is known as the Novita project – named after the town of Novita about 100 km from the city of Medellin.

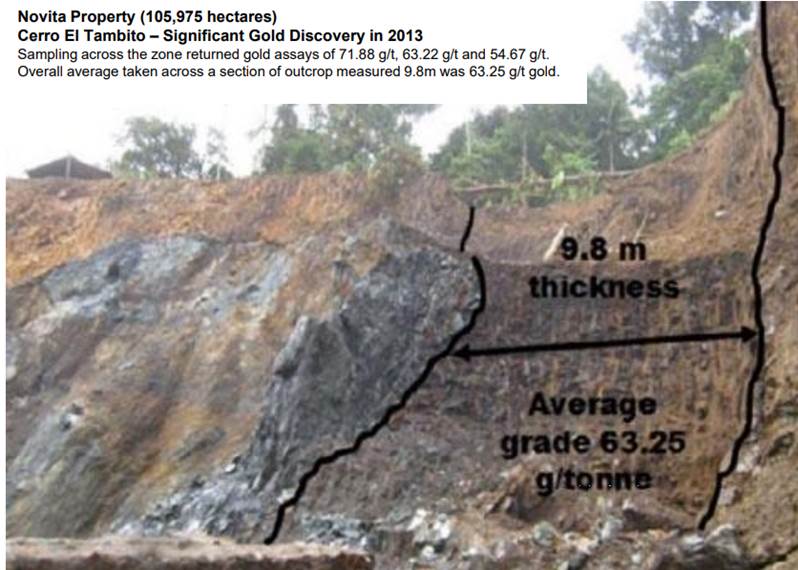

The other important aspect to the letter of intent was the rights to explore an area encompassing just over 1,000 square kilometers, that had yielded a historical 605,110 ounces of gold in exposed gold conglomerates. Other discoveries within the 1,060-square-km tenure included one historic mine that uncovered conglomerates over 3,200m by 800m, and the El Tambito shear zone, which returned three continuous channel gold assays of 71.88 grams per tonne, 63.22 g/t and 54.67 g/t over 9.8 meters, averaging an eye-popping 63.25 g/t gold. An associated grab sample returned 220 g/t gold.

Conglomerate gold caught the mining world’s attention two years ago when a couple of dozen companies flooded into the Australian Pilbara – better known for iron ore than gold – in search of gold nuggets in geological terrain thought to be similar tothe Witwatersrand Basin in South Africa, the world’s largest depository of gold.

One of the first companies in the Pilbara was Novo Resources (TSX-V: NVO), which cut a joint venture with Artemis Resources (ASX: ARV) after announcing it had found gold nuggets shaped like watermelon seeds at its Purdy’s Reward property. Canadian gold producer Kirkland Lake Gold (TSX: KL) invested C$56 million into Novo, as did kingmaker Eric Sprott, who took positions in several companies exploring in the new Pilbara area play.

In the summer of 2017 Novo Resources’ stock shot up 700%, and at one point the once-tiny junior had a plus billion-dollar market cap.

Back to Max Resource, the 2018 letter of intent between Max and Noble Metals was superseded by a Jan. 19 agreement between the two parties.

Under the Noble transaction, Max acquired a Noble subsidiary called Condoto Platinum Ltd. – for $500,000 plus the issuance of 26.6 million MXR shares.

Rolling the Noble transaction into MXR’s recently staked Chocó Precious Metals Project, Max Resources now has control over 89 mineral license applications and partial ownership of seven applications, spread over a whopping 1,757 square kilometers.

Moreover, the project is either part of, or adjacent to, the Chocó Precious Metals District. Between 1906 (gold price was US$21 per/oz) and 1990 (gold price was 383 per/oz), Colombian mining company Chocó Pacific extracted 1.5 million ounces of gold and a million ounces of platinum from the district, all within 8 meters of surface.

Max also owns the Gachala Copper Project 60 kilometers east of the capital, Bogotá. Located in a sedimentary copper basin comparable to the Zambian Copper Belt, historical sampling has identified a 24-kilometer strike length, with copper grades ranging from 0.5% to 13%. Anything over 1% is considered high-grade copper. A 4-km cobalt anomaly has also been identified.

Max’s priority is to go after the gold bearing conglomerates in the Chocó project and prove they are of substantial scale.

Matich was appointed CEO in February 2018 and Hayden is on the management team, along with chief operating officer Robert Matthews and chief financial officer Alex Hemel.

Last year the company raised $3.2 million in a 15-cent financing in May 2018, with each unit holder entitled to a 25-cent warrant, exercisable for two years. David Boehm’s Folkston Investments Ltd financed $1 million of the $3.2 million and at 12% holding is the largest single shareholder of Max. David is a long-term supporter of Bill Hayden and Robert Friedland.

Chocó Precious Metals Project

According to historic reports from Chocó Pacific, the hard-rock areas underneath the alluvial cover, where the gold in rivers has previously been mined, “are gold-bearing, extensive, shallow and generally flat lying with thicknesses from a few metres to 20 metres.”

Max therefore aims to substantiate reports of free gold (i.e. the gold is in a free state, uncombined with other metals) within the hard rock conglomerates and underlying the surface gold-bearing mineralization, and to determine the thickness of the gold conglomerate and how far it extends laterally.

Before getting into the nitty gritty of how Max plans to develop the project, a little background on Chocó is helpful to put it in context.

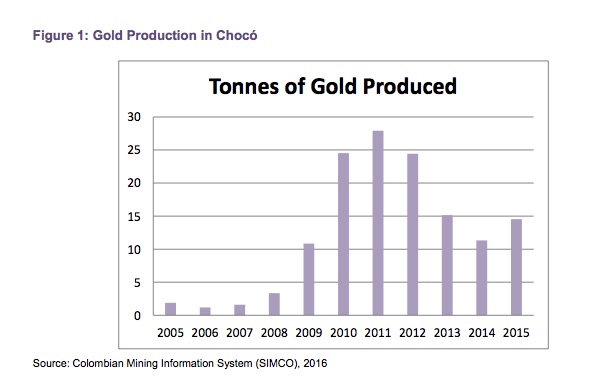

The region produces about a quarter of Colombia’s gold, mostly from alluvial (riverbed) sources and 99% of the country’s platinum.

An OECD report on Chocó mentions that despite mining authorities delivering 47 mining titles to major gold miners over the past decade or so, no companies have yet started mining in Chocó.

This means that Max could become a first mover, as it progresses its 1,757 sq. km of the Chocó Precious Metals District. Its agreements with the pro-mining indigenous groups in Chocó are the first since 1990. The company has also staked all the mineral claims in the area, thus locking out any competition.

So how is it Max going about exploring this massive, and highly prospective, conglomerate gold-platinum property? The breakthrough came in late 2018, when Max began targeting exposed conglomerate areas, where previous alluvial mining had been done, and taking bulk samples.

Bulk sampling on steroids

In a normal exploration program, a company makes extensive use of various boots on the ground geo-chem and airborne geo-physics programs to acquire the data needed to set up drill locations. A company usually wouldn’t take bulk samples until later stages, usually during prefeasibility. The larger bulk samples of mineralized material allow the company to run tests on how it will be processed.

Remember Max’s priority is to 1) substantiate reports of free gold within the hard rock conglomerates and 2) to determine the thickness of the gold conglomerate and how far it extends laterally. At the Chocó Precious Metals Project, the nature of the suspected mineralization pattern – flat-lying, near surface, possibly running for several kilometers – means that bulk sampling is suitable for delineating the gold at this earlier exploration stage.

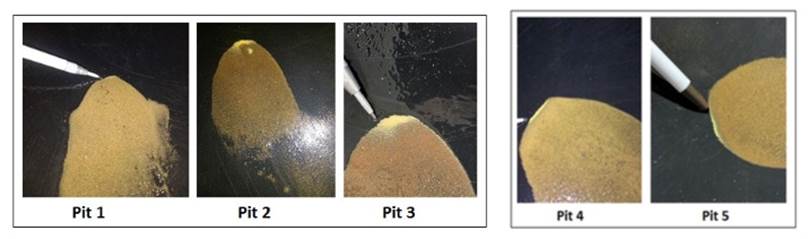

Max has conducted a six-pit 2m by 2m by 30cm-deep bulk sampling program, spread over an 8 sq. kilometer area.

About 2,500 kilograms of hard rock conglomerate was randomly collected from each pit, then a 50-kg sample from each pit was sent to a lab in Medellin, where it was crushed to <2mm, then gravity-separated to reveal the gold.

Samples from a 12m-high outcrop – a guide to the thickness of the gold bearing conglomerates – have also been sent to the lab for analysis.

So far five of the six samples have come back, and every sample contains gold.

“It’s pretty impressive when you’re getting that amount of visual gold out of samples that are from 27 to 50 kilos,” Max CEO Brett Matich commented on the results, published in a Jan. 30 news release.

“We’re looking at the enormity of scale. If you work out the volume of material in the 8 square kilometers at a 12-meter thickness, it comes out to a substantial amount of material. You’re talking potentially one of the largest hosts of mineralization on the planet. That’s what we’re looking at.” he told Ahead of the Herd in an interview this week.

He noted Max’s bulk sampling technique is similar to what Novo Resources (TSX-V: NVO) did in the West Pilbara; however, the difference between the two, is that the free gold in Chocó is much finer. Novo had a problem with the gold at Purdy’s Reward because it had an irregular, patchy distribution. Geologists call this discontinuity “the nugget effect”. It makes delineating a resource extremely difficult.

According to Matich, no such problem exists at Chocó. ” We think this area is going to be substantially more uniform than what Novo have,” he said.

If the plan for the bulk sampling program is to 1) substantiate reports of free gold within the hard rock conglomerates and 2) to determine the thickness of the gold conglomerate and how far it extends laterally Max is off to an incredible start.

Max will continue to keep doing bulk sampling in order to demonstrate the substantial size (and confirm gold distribution) of the potential deposit. At that point Max would be open to bringing in a partner, likely a mid-tier or major gold company, and/or an equity financing for what would be an enormous drill program, there is also the potential for a take out of Max.

For now, though, bulk sampling has one big advantage over drilling. While drilling can determine gold grades, fire assays can’t tell anything about how the gold should be processed. A bulk sample can. Max is currently using simple, inexpensive gravity processing to determine how much gold is in each (roughly) 50-kg sample. If a mine could eventually be developed and the ore gravity-processed, it would make for extremely attractive economics.

A bright future

It’s true that Colombia has, in the past, had its difficulties, but things have improved immensely.

Last year a new pro-business president Ivan Duque was elected, who appears friendly to mining. And unlike neighboring Venezuela, which is going off the rails economically, on its way to a failed state, or Bolivia, where President Morales has his finger on the resource nationalism button, in Colombia, the government has never repatriated any mineral titles.

A tax bill introduced in November that includes a 5% corporate tax cut is being lauded by the Colombian Mining Association for helping to make Colombia more competitive with Peru and Chile.

Enormity of Scale

One of the most important factors a mining company looks at, when considering whether to buy out a junior or its property, is scale. The large gold companies are facing the challenge of declining ore grades, depleted mines and a lack of new projects in the pipeline. We agree with many who argue we’re at “peak mined gold”; production is falling, and there is a lack of discoveries to take up the slack.

All the macro factors in place for a big gold run

Max Resources’ Chocó Precious Metals Project is on track to having the scale to interest a major. MXR is a first mover in the region, similar to Novo Resources (TSXV: NVO), which made huge stock price gains in Australia a couple of years ago. If they do well, more juniors are sure to follow, trying to replicate their success.

So far, they’re batting a thousand: free gold was found in every test pit so far. And they’ve only just begun: The first six bulk samples were over 8 square kilometers; that leaves nearly 1,750 square kilometers more available for testing! And let’s not forget, the deposits are all near surface.

Conclusion

Free gold means the possibility of low-cost processing: no heap-leach pads, no flotation, just good old-fashioned gravity as the means of separating the gold, not much different from old-school gold panning. We’re talking low-cost.

Combine these factors with the fact that Colombia is open for business with a pro-mining president, and that Max has an excellent team with deep experience including the co-founder geologist of Ivanhoe Mines, and this project begins to look very impressive indeed.

The Spanish never found their El Dorado. Max Resources (TSX.V: MXR) might have found theirs.

“We believe the underlying conglomerates are potentially the source of the historic surface production of 1.5Mozs gold and 1.0Mozs platinum. The historic production may have only been scratching the surface of a significant underlying gold system.” Management, Max Resources

For all of these reasons I have MXR on my radar screen.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd is on Twitter

Ahead of the Herd is now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd is now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Max Resource Corp (TSX-V: MXR) is an advertiser on Richard’s site aheadoftheherd.com. Richard owns shares of MXR.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.