Goldcorp-Newmont deal points to more M&A

2019.01.15

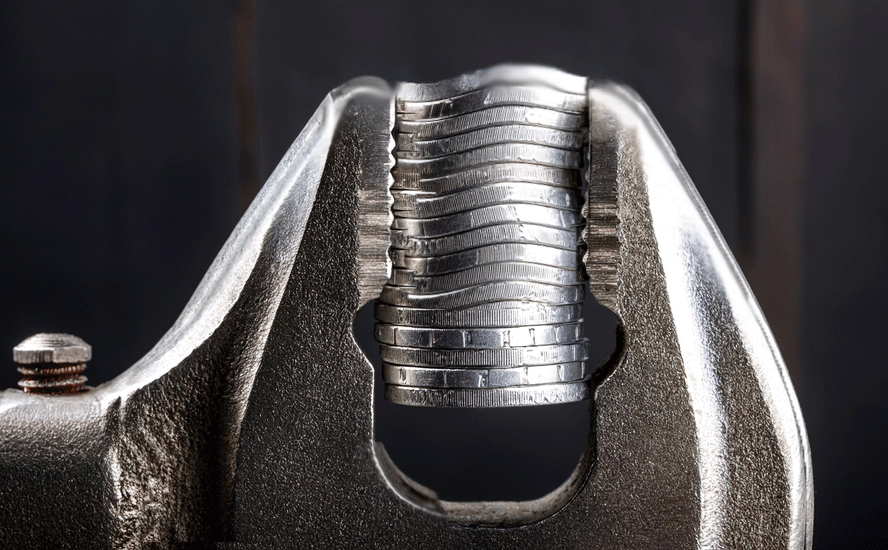

More gold mines will be going on the block thanks to a blockbuster gold mining company tie-up announced Monday. And major gold companies will also be looking to acquire large, preferably high-grade deposits, due to the ever-present problem of depleting mine reserves, as extraction costs become more expensive and profit margins squeezed without a significant rise in the gold price.

These are the two main takeaways from the merger of Goldcorp and Newmont Mining which creates the largest gold company in the world – knocking “New Barrick” (the merged Barrick Gold and Randgold) off the top of the pedestal.

The consolidation started with the takeover of Africa-focused Randgold by Barrick in September; the all-share deal was worth $6.5 billion. After years of languishing gold and gold mining stock prices following gold’s record price of $1,900 an ounce in 2011, some of the biggest gold miners are finally ready to raise the white flag – overwhelmed by eroded profit margins amid (relatively) low gold prices compared to the 2011 top, and higher costs of production.

The gold price was down 5% in 2018 due mostly to the appreciation of the US dollar throughout last year and steady demand for US Treasury bills (for more on that read our Gold and the great stage of fools). More importantly though, gold is getting harder to find.

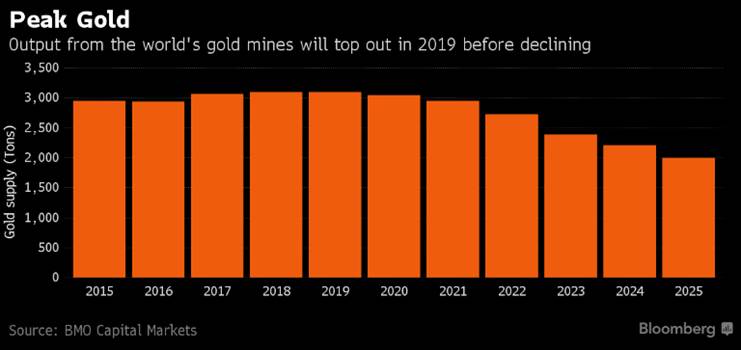

Mine production falling

The mined supply of the precious metal is shrinking as most of the “low-hanging fruit” has been mined and the rest is either in remote locations or buried deep in the earth, meaning higher extraction costs.

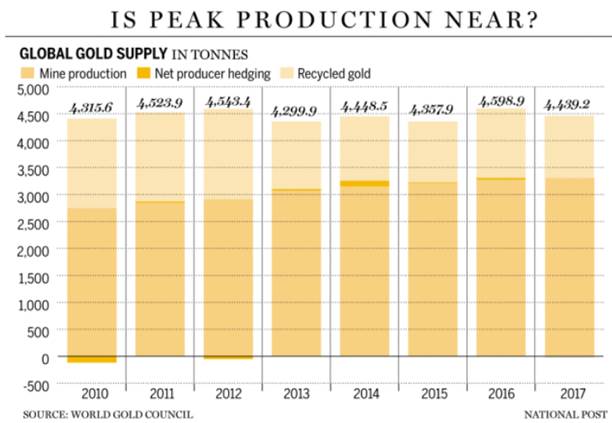

2016 was the first year that mine production fell since 2008. In spring 2018 the World Gold Council in its annual gold trends report said that total gold supply slipped in 2017 to 4,398 tonnes – a drop of 4% from 2016. Mine production was about the same as last year, 3,268.7 tonnes, but recycled gold fell 10% to 1,160 tonnes. Key gold producers that saw drops in 2017 were China and Tanzania.

Global gold-mine discoveries reached their peak in the early 1980s according to data from specialists MinEx Consulting.

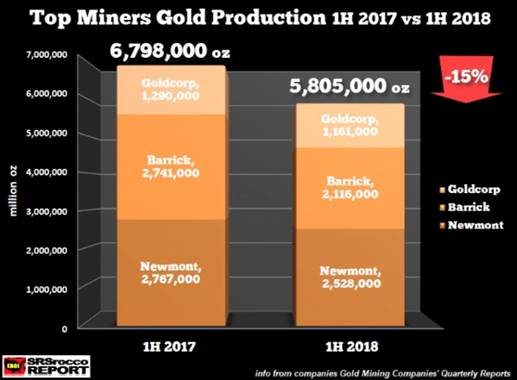

In the first half of 2018 output the top three gold miners – Barrick, Newmont and Goldcorp – fell 15% compared to H1 2017, at the same time as the oil price climbed, meaning cash flow fell off a cliff.

Falling production has been a trend for some time, that will eventually signal a move up in price.

South African gold production has plummeted below 250 tonnes compared to 1,000 tonnes in the 1970s, and China, the leading gold producer, is the only country to increase production in recent years, notes Goldcore via ZeroHedge.

Lower grades, higher costs

Why is production falling? For the most part it’s due to lower grades. In 1998 Barrick was producing gold, mostly from its Nevada operations, at 9.6 grams per tonne. As Barrick added more mines its production rose, peaking in 2006 at 8.6 million ounces, but its average yield was 1.71 g/t. The company’s production and grades have both fallen since then, producing 5.3 million ounces in 2017 at 1.68 g/t.

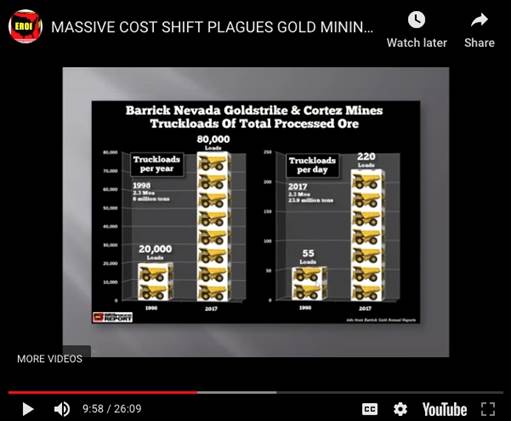

The lower grades have meant production costs have risen significantly. As shown in the slide below, in 1998 Barrick needed 55 loaded trucks a day to move 2.3 million ounces at its Goldstrike and Cortez mines. In 2017 it had to load 220 trucks per day to produce the same amount of gold. That’s a four-fold increase in the amount of ore needed to be transported, resulting in much higher fuel, labor and processing costs.

MINING.com reported that gold mining costs are up 22% since the gold price bottomed out in the first quarter of 2016.

Victims

Between the first half of 2017 and the first half of 2018, production from the top three gold miners Barrick, Newmont and Goldcorp – fell 15%.

Analyzing the financial performance of the top three, SRSrocco Report concluded that “The biggest loser was Barrick, whose production declined over 20% by falling to 2.1 million oz in 1H 2018 compared to 2.7 Moz in the previous year. Goldcorp’s production fell 10%, while Newmont’s output dropped by nearly 9%”.

In the first half of 2018 free cash flow at the combined top three plummeted from $718 million in the first half of 2017 to just $38 million in H1 2017.

Seeking Alpha went further in an October 2018 analysis. Combining data from the three largest gold companies, Simple Digressions found that revenue in the first three quarters of 2018 dropped by 9.4% versus Q1, 2 and 3 of 2017. Comparing the same periods, the amount of gold the top three sold fell 11.3%. A higher unit cost of production ($674 per ounce in the first 9 months of 2018 versus $610/oz in Q1, 2 and 3 of 2017) meant a $3.3 billion gross margin for the first three quarters of 2018 versus $4.1 billion in the first 9 months of 2017.

Goldcorp is clearly the best example of a gold miner in distress. In a timely article published the weekend before the $10-billion Goldcorp-Newmont deal, the Globe and Mail noted that Goldcorp’s shares on Friday traded for $12.86 apiece versus $54 in 2011 – a 17-year low.

CEO David Garofalo has been heavily criticized over the insipid stock price, but the trouble started before he took over in 2016. Goldcorp made some really dumb moves at the top of the mining supercycle, and has a string of missed targets. In 2006 it paid US$430 million for the Eleonore project in Quebec. The mine was supposed to produce 600,000 ounces of year but in 2018 only managed 350,000 oz. The Cocheneur development property in Ontario was initially touted as a 5 million ounce deposit, but has since been downgraded to 300,000 ounces in reserves. Another recent disappointment was the Coffee property Goldcorp bought from Kaminak Gold for $530 million. Infill drilling recently cut the reserves by 23%, to 1.7 million ounces.

“In general the world’s production is on the verge of a sharp decline due to the development of previously proven reserves and the lack of new discoveries.” Andrey Lobazov, mining analyst at Aton

In 2017 Goldcorp paid over half a billion dollars for a 50% stake in the Cerro Casale mine in Chile, but nothing has happened, with the project considered too low grade, too remote, and too expensive to develop, the Globe and Mail reported. Same with another project Goldcorp bought in Chile, Caspiche – the company has yet to convert its 12.5 million ounces into reserves.

Despite all of these mis-steps, Goldcorp was Canada’s second largest gold producer and the third largest in the world by market value, before Monday’s takeover.

Targets?

Given the poor performance of the top three gold miners, who could be the next M&A targets? Bloomberg names AngloGold Ashanti, Newcrest and Kinross Gold as possibilities. The publication also won’t rule out New Barrick (doesn’t that sound weird?) for further deal-making, quoting its new CEO, Randgold’s Mark Bristow, saying they are not “going to be sitting on our hands should there be other opportunities.”

Bloomberg also states that with two huge deals in the gold sector recently signed, “the pressure on those left behind will be even greater”:

The two mega deals promise to transform the industry that many investors have shunned due to floundering bullion prices and poor decision making by producers. The newly combined companies are also expected to put several unloved assets up for sale, leaving lots of room for maneuvering by those that missed out on the dealmaking so far.

Newmont has said it would sell a billion to $1.5 billion in assets over the next two years.

Big deposits scarce

The bear market of 2012 to 2016 meant most large gold companies slashed exploration budgets and small explorers had an extremely tough time raising cash. The industry is seeing a significant slowdown in the number of large deposits being discovered. Frank Holmes quotes Franco-Nevada co-founder Pierre Lassonde saying recently that he doesn’t know how we’ll replace the massive deposits found over the last 130 years:

“If you look back to the 70s, 80s and 90s, in every one of those decades, the industry found at least one 50+ million ounce gold deposit, at least ten 30+ million ounce deposits and countless 5 to 10 million ounce deposits. But if you look at the last 15 years, we found no 50 million ounce deposit, no 30 million ounce deposit and only very few 15 million ounce deposits,” states Lassonde.

“The future pipeline is [now] almost devoid of ‘world class’ projects. Gold production [must either] be sourced from a greater number of smaller operations, or face a sharp contraction in capacity,” Mark Fellows, Metals Focus’ head of mine-supply analysis

Discoveries have indeed tapered off. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, between 1999 and 2017 there were 222 discoveries, compared to just 41 in the 10 years before 2017. In 2017 no discoveries were made.

As high-grade reserves are depleted (refer to the Barrick example above), and costs rise, gold miners are being forced to be more efficient and to acquire new deposits to replace their reserves.

This of course is good news for our junior miners, whose job in the mining food chain is to keep the supply of minerals moving, through discoveries that are usually bought, either through project purchases or company acquisitions, by larger mining companies.

Simple economics also dictates that as supply diminishes, the price will go up. Considering the rarity of gold – it is present in much smaller quantities than other metals – the fact that production is decreasing, and that new discoveries are few and far between, we are setting up for a continued rise in the gold price, irrespective of investment and jewelry demand.

Last week we reported that the price is ticking up so far this year, helped by a lower US dollar and higher demand from ETF holders and central banks. Ross Norman, CEO of Sharps Pixley, notes this week that the gold price is currently within a few percentage points of being at an all-time high in 72 currencies, not including the US dollar.

The recent M&A is great news for the gold industry and the gold juniors. I’m looking forward to seeing who comes forward with the next major deal.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.