Feeding the world vs saving the planet

2019.10.05

When China closed its door to all US agricultural exports in August, farmers in South Dakota were badly hurt. The Asian country at trade war with the United States buys 70% of the MidWestern state’s soybeans – making it an income staple.

South Dakota’s economy gets 25% of its revenue from agriculture, more than any other industry. The trade war is biting South Dakotan farmers worse than a soybean cyst nematode. A second-quarter survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis found 3 of 4 respondents reported lower net farm revenue.

Losing their biggest trading partner must have seemed like a silo-sized hole in the head that farmers didn’t need, given the horrible weather they were coping with.

A very wet spring meant MidWest farmers were unable to plant their crops. The US Department of Agriculture estimates unplanted acreage to be as high as 15 million for corn, almost five times a 2013 record of 3.6 million acres.

Corn that was planted, received too many hours of sunlight, killing a large portion of the plants that managed to sprout.

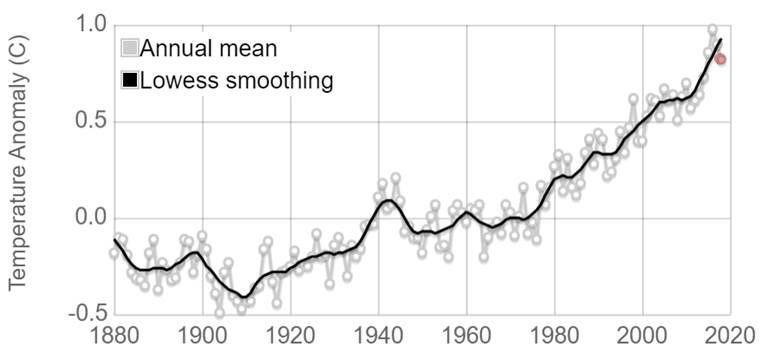

Temperatures in the fields keep getting hotter. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, 2018 was the fourth-warmest year on record since 1880; the only three hotter years were 2015, 2016 and 2017.

That concerns the US Department of Agriculture, which commissioned a report that found if temperature raises caused by climate change continue, US production of corn and soybeans, which are susceptible to extreme heat during growing season, could decline as much as 80% in the next 60 years.

The loss of production would not only hike prices, it would also mean a major spike in the cost of crop insurance, paid for by the federal government.

Reporting on the USDA’s findings, the Wall Street Journal cited data from the US Environmental Protection Agency stating that greenhouse emissions connected to global heating shot up 3.4% in 2018, due to a surge in the US economy. That’s more than twice the 1.3% rise from 1990 to 2017 and the largest jump since 2010.

Effects on US farming

Some of our readers skeptical of climate change science will be heartened to read that at Ahead of the Herd, we don’t believe global warming is man-made.

Increased greenhouse gases from the industrial era are only partly to blame. There is actually very strong science to indicate global temperature increases are down to climate cycles that don’t change for thousands of years. It’s a valid argument to say that anthropogenic emissions have sped up what was already happening naturally.

This is the same view of Forbes columnist Marshall Shepherd, a meteorologist whose bio states he is “a leading international expert in weather and climate,” as well as the former president of the American Meteorological Society (AMS).

Shepherd writes, While contrarians will roll out the cliche “these things happen naturally” narrative (by the way climate scientists know this so please stop telling us), studies increasingly affirm that drought, heavy rainfall, and some aspects of hurricane activity are changing because of the anthropogenic “steroid” on top of natural variability.

So what is the impact of climate change on US agriculture?

A 2013 USDA report on climate and agriculture found the benefit of more carbon dioxide (ie. the absorption of more CO2 from plants requiring carbon dioxide for photosynthesis) is far outweighed by the negative impacts of rising temperatures and rainfall variations on crop and herd productivity. No surprise there.

Digging a little deeper, pun intended, one finds that the industrial model dominating American agriculture makes it especially vulnerable to climate changes. Consider cattle ranching, which accounts for a whopping 50% of US agricultural revenue.

Raising cattle for beef consumption reportedly requires 28 times more land, 6X more fertilizer and 11X more water compared to pork, chicken, dairy and eggs. Not only does industrial-scale beef production use a heck of a lot of resources, it’s also harmful to the environment, emitting about 200 kilograms of CO2 per kg, five times other food sources, and sucking up about 15,000 liters of water per kilo.

Hotter summers in cattle country are putting more pressure on bovine demands for water.

Extreme heat and more temperature fluctuations are hard on plants. Fewer cold days in the winter can mean some pests don’t die off, staying alive until the next season when they wreak havoc. Insects that didn’t use to be a problem may suddenly show up, having found a previously inhospitable climate now suitable, as a result of warming.

Heavy rains cause flooding, which can devastate crops and livestock, accelerate soil erosion and pollute water. The other extreme, droughts, can be exacerbated by rising temperatures, reducing crop yields and causing irrigation water shortages. Crops near coastal areas can also be ruined by saltwater intrusion as a result of storm surges or rising seas.

Industrial farming also tends to rely too much on fertilizers and pesticides.

The Union of Concerned Scientists notes that monoculture – repeatedly producing the same crop at the exclusion of others – is bad for the soil, preventing the formation of deep root systems and the buildup of organic matter, and hastening the time when the soil can no longer holds its nutrients and irrigation ends up stripping nitrates out of the soil and polluting nearby fresh water supplies:

Typical monoculture cropping systems leave soil bare for much of the year, rely on synthetic fertilizer, and plow fields regularly. These practices leave soils low in organic matter and prevent formation of deep, complex root systems. Among the results: reduced water-holding capacity (which worsens drought impacts), and increased vulnerability to erosion and water pollution (which worsens flood impacts).

The industrial farm’s heavy reliance on fertilizers and pesticides may become even more costly to struggling farmers as climate impacts accelerate soil erosion and increase pest problems. Heavy use of such chemicals will also increase the pollution burden faced by downstream communities as flooding increases. Farmers may also increase irrigation in response to rising temperature extremes and drought, further depleting precious water supplies.

Nationwide, reductions to agricultural productivity or sudden losses of crops or livestock will likely have ripple effects, including increased food prices and greater food insecurity.

Perpetrator and victim

In this way, it’s interesting to look at modern farming in the United States and other developed countries as both a “perpetrator and a victim” when it comes to climate change.

Society demands increased crop yields from agriculture in order to feed growing populations especially in the developing world.

Since 1950, the world’s population has gone from 2.5 billion people to 7.5 billion. No less than 75 million people a year are added to this number.

According to the United Nations, the world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by the year 2050. A 2017 study in the journal Bioscience suggested that to feed that number of people, global food production will need to increase from 25% to 70%.

The agricultural reforms and resulting production increases fostered by the Green Revolution are responsible for avoiding widespread famine in developing countries and for feeding billions more people since.

Unfortunately though, high-yield growth is tapering off and in some cases declining. This is mostly because of an increase in the price of fertilizers, other chemicals and fossil fuels, but also because the overuse of chemicals has exhausted soils and irrigation has depleted water aquifers.

Given this reality, “Climate change is acting as a brake. We need yields to grow to meet growing demand, but already climate change is slowing those yields,” Lifegate quotes Michael Oppenheimer, a professor at Princeton and co-author of the fifth report by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change).

Therein lies the quandary. We need higher crop yields to feed more people, but climate change is making that harder to attain.In fact rising temperatures combined with more intensive agriculture to produce higher yields actually creates a feedback loop, that pushes CO2 levels even higher.

Desertification is human-caused degradation of land, including unsustainable farming, overgrazing, clear-cutting, misuse of water and industrial activities. Climate change accelerates desertification because warmer temperatures dry out once-fertile land, which then makes the area even hotter. Removing plants from the ground also increases greenhouse gas emissions, since they can no longer serve as carbon sinks. As we strip away the amount of available land for food production, we are literally depriving ourselves of the means to survive.

Here’s how it works: Ranching and farming, through extensive energy inputs like diesel fuel, lights, heating, etc., generate high amounts of carbon dioxide. Farming also releases methane from cows and cow manure, and nitrous oxide from fertilizers. Both are heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

As farmlands expand to meet demand for more food, forests are destroyed to make room for crops. Trees are carbon sinks that trap CO2 and prevent warming. Their removal dampens the forests’ mitigating effects on emissions from farming, therefore temperatures continue to rise.

A good example is soybeans. 95% of the soy that is made from soybeans, is used as animal feed. To feed 700 million pigs in China – one for every two citizens – requires the importation of 800 million tonnes of soy. A lot of soybeans come from the Amazon region of Brazil, where rainforests, considered one of the most effective carbon sinks on the planet, must be logged to make room for more soybean farms.

Lifegate concludes: If greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase, as they are doing today, it will exacerbate those challenges and eventually make it all but impossible to control global warming without creating serious food shortages.

Feed the hungry or save the planet?

Research shows the human race is far over-extending itself and if reductions aren’t made or productivity doesn’t improve, it will eventually run out of food, rendering the Green Revolution a failure.

A report from the World Resources Institute concludes that feeding the world’s 9.8 billion in 2050 will require clearing most of the world’s remaining forests. The removal of the world’s carbon sinks would of course result in further warming, increasing the risk of crop failure and mass starvation.

In fact the UN’s often-quoted Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says we need to do precisely the opposite: shrink the amount of emissions-creating farmland and significantly increase the number of trees or other types of vegetation that can act as carbon sinks.

Unfortunately though, we appear no closer to achieving either objective. The planet continues to get hotter and climate change is reducing not only the quantity of food crops but the quality.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment found that climate change is already shrinking food supplies, particularly rice and wheat. More importantly in terms of ameliorating global famine, an estimated 795 million people still regularly don’t have enough to eat.

Disturbingly, the study quoted by The Conversation found that rising temperatures have reduced consumable food calories by 1% a year for the top 10 crops – maize (corn), rice, wheat, soybeans, oil palm, sugarcane, barley, rapeseed (canola), cassava and sorghum:

This may sound small, but it represents some 35 trillion calories each year. That’s enough to provide more than 50 million people with a daily diet of over 1,800 calories – the level that the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization identifies as essential to avoid food deprivation or undernourishment.

The apparent return of world hunger after half a decade of decline (2014 to present) is alarming.

Will future world leaders have to choose between feeding the world and destroying the planet, or saving the planet and letting people go hungry?

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.