Peak gold – Richard Mills

2026.02.03

Gold mines have been mining at a higher grade than the reserve grade for much of the last decade. Purposely mining areas of the orebody with the highest-grade material is known as high grading.

Mining the high-grade accessible areas of their deposits was one way for operations to bolster margins when facing low metal prices.

Small wonder the #1 risk identified for mining companies over 2026 is rising operational complexity which is being driven by more complex ore bodies, much deeper mines and significantly declined ore grades. And mining capital is increasingly favoring brownfield expansions, which offer 50% to 70% faster production timelines compared to new greenfield projects.

The concept of peak gold should be familiar to most readers. Like peak oil, it refers to the point when gold production is no longer growing; It reaches a peak, then declines.

If gold is indeed becoming scarcer, prices have only one way to go and that’s up, so long as demand for the precious metal is constant or growing, which it is.

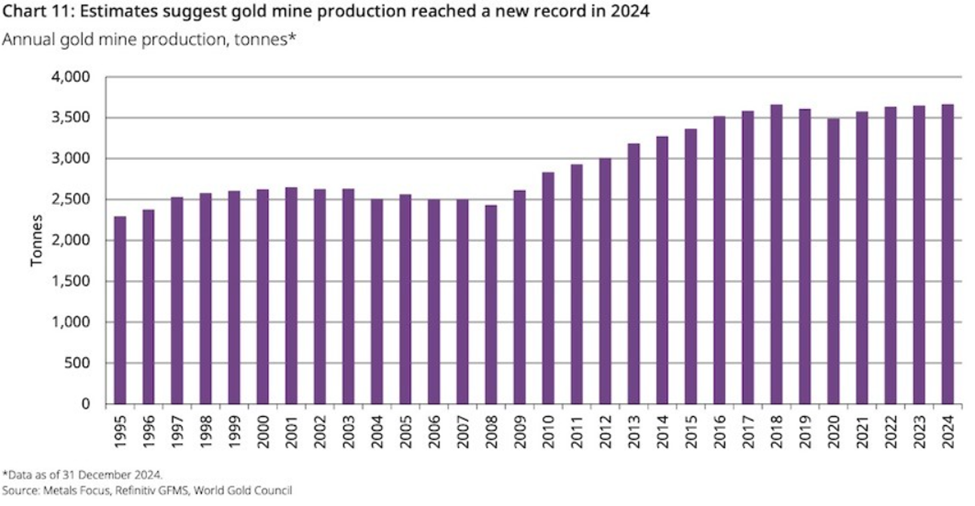

The latest full-year World Gold Council report shows a 1% increase in total gold supply in 2024, compared to 2023, 4,974.5 tonnes versus 4,945.9t. In fact, gold supply in 2024 surpassed the record reached in 2018.

According to WGC, 2024 mine production reached an all-time high of 3,661.2 tonnes, beating 2023 mined output and just surpassing 2018’s record 3,656t.

In 2024 total gold demand (including OTC investment) rose 1% y/y in Q4 to reach a new quarterly high and contribute to a record annual total of 4,974t.

The World Gold Council (WGC) reports that 2024 mine production was 4,974.5t.

Gold jewelry recycling was 1,370t, bringing total gold supply in 2024 to 4,974.5t.

If we stop there, we show that mined gold supply exactly meets gold demand at 4,974t. No peak gold here, right? Demand is satisfied by supply.

Not so fast, let’s think about those numbers for a minute. In calculating the true picture of gold demand versus supply, we, at AOTH don’t, and won’t, count jewelry recycling. What we want to know, and all we really care about, is whether the annual mined supply of gold meets annual demand for gold. It doesn’t! When we strip jewelry recycling from the equation, we get an entirely different result. i.e. 4,974 tonnes of demand minus 3,661.2 tonnes of production left a deficit of 1,312.8 tonnes.

This is significant, because it is saying even though major gold miners are high grading their reserves, mining all the best gold and leaving the rest, they still didn’t manage to satisfy global demand for the precious metal, not even close. Only by recycling 1,370 tonnes of gold jewelry could demand be satisfied.

This is our definition of peak gold. Will the gold mining industry be able to produce, or discover, enough gold, so that it’s able to meet demand without having to recycle jewelry? If the numbers reflect that, peak gold would be debunked. We’ve been tracking it since 2016, and it hasn’t happened yet. We have already talked about 2014, below we’ll go down to 2016.

2023 mine production of 3,644.4 tonnes fails to meet gold demand of 4,898.8t, even by recycling 1,237.3t. (short 17.1t)

2022 mine production of 3,611.9 tonnes fails to meet gold demand of 4,741t, without recycling 1,144.1t.

2021 mine production of 3,560.7 tonnes fails to meet gold demand of 4,021t, without recycling 1,149.9t.

2020 mine production of 3,400.8 tonnes fails to meet gold demand of 3,759.6t, without recycling 1,297.4t.

2019 mine production of 3,473.7 tonnes fails to meet gold demand of 4,355.7t, without recycling 1,304.1t.

2018 mine production of 3,346.9 tonnes fails to meet gold demand of 4,345.1t without recycling 1,176.2t.

2017 mine production of 3,268.7 tonnes fails to meet gold demand of 4,071.7t without recycling 1,160t.

2016 mine production of 3,236 tonnes fails to meet gold demand of 4,308.7t without recycling 1,308.5t.

In a world of resource depletion, it falls to gold exploration companies to fill the gap with new deposits that can deliver the kind of production required to meet gold demand, which is currently out-running supply.

Wood Mackenize says to avoid a perpetual decline in mined gold; the industry must see a rise in the number of gold projects under development that have a good chance of becoming mines.

How many projects? 44, to be exact.

Intuitively, that seems virtually impossible – Wood Mackenzie agrees.

“If all our probable projects were to come online before 2025, this would almost meet the requirement to maintain 2019 production levels,” said Rory Townsend, Wood Mackenzie’s head of gold research.

“The likelihood, however, is that we see some degree of slippage among a number of these assets due to permitting delays, prioritization of other capital projects and changes in scope,” said Townsend.

Consider: in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, the gold industry found at least one +50Moz gold deposit and 10 +30Moz deposits. Since 2000, no deposits of this size have been found, and very few 15Moz deposits.

Don’t believe us? Here’s Ian Telfer, former Goldcorp chairman, and gold industry expert, giving his argument for peak gold, in 2018:

“In my life, gold produced from mines has gone up pretty steadily for 40 years. Well, either this year it starts to go down, or next year it starts to go down, or it’s already going down… We’re right at peak gold here.”

To get world gold mine production back to the point where it can meet the required annual demand without recycling jewelry, the industry has two choices: it can mine more gold, or it can discover new gold.

Squeezing more gold out of existing deposits has its challenges. Reserves are getting depleted, and mines are having production problems, including lower grades, labor disruptions, protests, etc.

But finding and exploiting new gold deposits is even harder, more expensive and riskier.

Few gold exploration projects have the economics, scale, jurisdiction and money-raising capabilities backing them, to become mines. Those with the staying power to make it through the various development stages, from initial discovery to drilling to resource definition to first production, will be the belle of the ball, so to speak, with many major gold miners cueing up for the first dance.

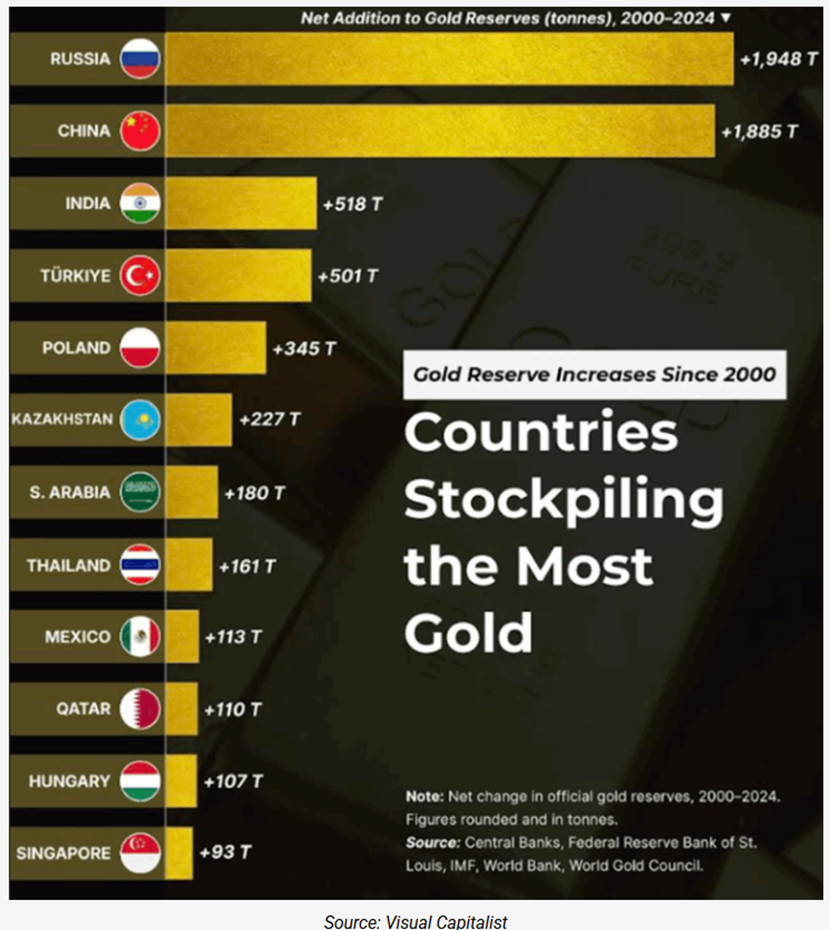

Central banks worldwide are on track to buy slightly less then 1,000 tonnes of gold in 2025, which would be their fourth year of massive purchases as they diversify reserves from dollar-denominated assets into bullion, consultancy Metals Focus said, via Reuters.

French bank Société Générale (Soc Gen) upped it’s gold allocation from 7% to 10% for a protective hedge as the US Federal Reserve begins a rate lowering in the face of rising inflation. The French bank expects gold prices to average $3,825 an ounce, and to average $4,128 an ounce in 2026.

“From an asset allocation perspective, we have looked at gold in the context of the USD’s dominance being challenged. The key drivers supporting gold remain firmly intact,” the analysts said.

They added that they expect gold prices to remain well supported as falling interest rates and elevated inflation push real yields lower, increasing demand for gold as an alternative store of value.

At the same time, the analysts said that the ongoing global diversification trend away from the U.S. dollar makes the precious metal an important monetary asset. They added that they don’t expect higher prices to be a barrier to further central bank purchases.Neils Christensen, Kitco

War drums are beating and a crisis is unfolding in the bond market that equity investors may not be aware of. Long-term government bond yields are rising across major economies as governments struggle to contain mounting debt burdens. If the government can’t find enough foreign buyers to sop up its debt, the Fed will have to step in and buy Treasuries, much the same as it did during the quantitative easing that accompanied the financial crisis and the covid-19 pandemic. This, of course, is highly inflationary.

Inflation not only raises consumer and producer prices, but it also devalues the currency, i.e., the US dollar.

“There have been no major discoveries, no meaningful supply response, while demand continues to rise structurally, all while a monetary crisis quietly builds. This is the kind of price behavior typically observed in emerging markets when confidence in the currency is eroding.” Tavi Costa

Gold demand is climbing in the face of structural supply problems. Our gold industry is in trouble.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.