Why Copper Incentive Pricing and increasing M&A matters to owners of BC copper and gold projects – Richard Mills

2025.12.23

The incentive price for copper is the minimum market price needed for mining companies to justify investing in new, large-scale mining projects or to significantly expand existing production. It represents the cost threshold required for a project to be economically viable, ensuring a specific return on investment.

Many analysts place the current incentive price for new project ranging from $11,000/ton ($5.50/lb) up to $13,000/ton ($6.50/lb).

The primary factors driving copper price incentives are a significant surge in demand driven by global electrification, the energy transition and the rapid growth of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Data centers: Gluttons for power, water and minerals Part I

The associated increase in data centers is causing an explosion in electricity demand, requiring substantial copper for new infrastructure and power transmission.

Copper is vital to artificial intelligence and the infrastructure that supports AI. Copper’s used in computers, and in the reams of wiring required by data centers, and of course in power transmission to all the new data centers.

Data centers: Gluttons for power, water and minerals Part II

Along with all the usual applications for copper — in construction, transportation and telecommunications — demand is being driven by on-going electrification and decarbonization of the transportation system and the exponential growth in battery storage.

This all boils down to everything driving the world’s economies needs more copper, in the face of persistent constraints on mining supply.

Mine disruptions like the recent Grasberg mine mud intrusion in Indonesia, and the flooding at Ivanhoe Mines’ Kakula mine in the Congo not only strip copper supply from the global market and drive up the price but they also highlight just how volatile the copper market is when one mine closure and then another leaves it vulnerable to price spikes from any supply disruption or demand surge.

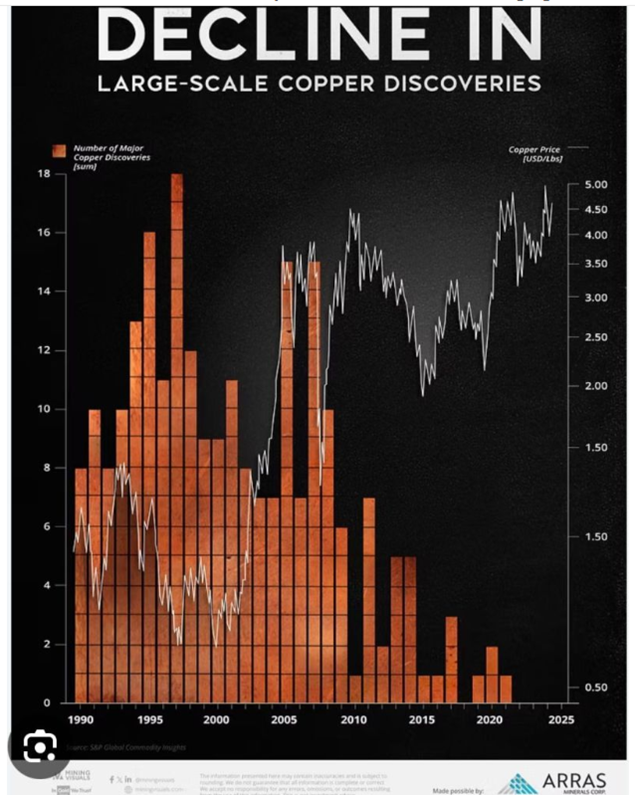

There has been a dearth of new copper discoveries in recent years, and the grades of existing copper mines are dropping, which, when added to operational misses, are making the supply problem worse.

The problem is the low-hanging fruit’s been picked. It’s very hard to get a large new discovery of over 200,000 tonnes a year.

There are few new copper mines being built and the ones that are usually have offtakes with Asian countries, not Western ones.

You would think that with copper, gold and silver prices all at record levels for the first time in decades, the money spent on building mines would be going up. Instead, aggregate capex is at one of its lowest levels in history. It’s 90% lower than its previous highs.

Historically, major mining projects have faced significant cost overruns (over 40% on average) and schedule delays (20-30%), further deterring new large-scale investments. The higher costs of building new projects make them harder to justify; miners need higher long-term prices to proceed.

For at least 2025, overall caution and a focus on financial resilience are expected to persist. The long-term underinvestment in new supply will create structural supply shortages, potentially driving mineral and metal prices higher in the future. More on this below.

Copper and AI

A big variable is demand from data center growth, which could translate into a 30% increase in copper demand by data centers next year, writes Gregory Shearer, head of base and precious metals strategy at JPMorgan, via Axios.

At U.S. Global Investors, Frank Holmes writes A conventional data center uses between 5,000 and 15,000 tons of copper.

A hyperscale data center, on the other hand—the kind being built to run artificial intelligence (AI)—can require up to 50,000 tons of copper per facility, according to the Copper Development Association…

Data centers currently consume about 1.5% of global electricity supply, roughly the same amount as the entire U.K., according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The organization believes that, by 2030, demand will more than double, with AI responsible for much of the increase. That means data centers could be consuming more than half a million metric tons of copper annually by the end of the decade.

Perhaps even more significant is Holmes’ remark that data centers are largely indifferent to copper prices. Despite the amount of copper in data centers, the cost is low. According to Wood Mackenzie, the metal accounts for just 0.5% of total project costs. That means data centers will be built whether copper is trading for $10/lb or $20/lb.

A hyperscale data center—the kind being built to run artificial intelligence (AI)—can require up to 50,000 tons of copper per facility, according to the Copper Development Association.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) believes that, by 2030, demand will more than double, with AI responsible for much of the increase. That means data centers could be consuming more than half a million tonnes of copper annually by the end of the decade.

An additional half-million tonnes doesn’t seem like a lot, but it will stretch miners to find that extra copper. Global mined copper production is about 22 million tonnes a year, but a shortfall of 30% is expected by 2035.

Permanent structural supply problem

S&P Global produced a report in 2022 projecting that copper demand will double from about 25 million tonnes in 2022 to 50Mt by 2035. The doubling of the global demand for copper is expected to result in large shortfalls — something we at AOTH have been warning about for years.

The copper market is expected to face its most severe deficit in 22 years in 2026 —590,000 tons — according to Morgan Stanley.

The deficit could widen by 2029 to a whopping 1.1 million tons.

According to the International Energy Agency, via Reuters, the capex required to get new supply up and running in Latin America, the nexus of global copper production (Chile, Peru), has increased 65% since 2020.

To build a new 200,000-ton-a-year copper mine, the upper end is $6 billion.

That implies up to $30,000 to build one ton of yearly copper production, a figure miners are not, so far, buying into.

It’s easy to see why miners are reluctant to build new mines and are instead relying on M&A to increase their reserves.

Recent examples include the merger between Anglo American and Canada’s Teck Resources to form a new company, Anglo Teck; BHP and Lundin Mining’s $38 billion joint venture to expand the Filo del Sol Project in Chile/ Argentina; and MMG acquiring Cuprous Capital to expand the Khoemacau copper mine in Botswana.

Codelco and Anglo American in September finalized an agreement to merge operations at their Los Bronces and Andina copper mines.

Many copper mines are decades old and reaching the end of their lives. Their owners can expand them, such as Newmont-Imperial Metals’ underground block cave operation at their Red Chris mine in northwest British Columbia, try to find more copper around the mine, or the most attractive option, buy other copper miners’ and add their reserves to your own.

It’s easy to see why copper mining companies prefer to “eat each other” rather than try to find new mines. It’s the path of least resistance. Unfortunately, this does nothing to alleviate the global copper supply deficit. It’s just shifting one pile of reserves in one mining company to another. The global reserves total doesn’t change. The deficit continues.

All it takes is one major copper mine to get shut down, and suddenly we’re looking at deficits. Electrification, AI, and all the above listed uses of copper are putting strains on the copper supply.

The obvious solution is to find more copper.

People are realizing that, whether it’s copper or gold, major new discoveries have dropped off a cliff. That has the industry focused on M&A, or cheaper, less risky, easier-to-get-into production brownfield projects.

Epicenter of Canadian copper production

Many hundreds of billions of dollars worth of copper-gold projects are locked up in the Golden Triangle of northwestern British Columbia. But the epicenter of Canadian copper production is in BC’s Quesnel Trough.

At least nine major or mid-tier mining companies are operating within the Late Triassic-Alkaline Cu-Au Porphyry Belt, including Taseko (Gibraltar mine), Boliden (Gjoll project), Teck (Highland Valley mine), Hudbay Minerals (Copper Mountain mine), Imperial Metals (Mount Polley mine), New Gold (New Afton mine), and KGHM (Ajax project). 54% of Canada’s copper is produced in BC.

The big dogs, including former gold only miners are in BC because they are looking for additional assets — especially copper-gold-alkalic-porphyry systems, which offer high-tonnage, long-life mines.

The wave of M&A currently sweeping across copper majors will trickle down the food chain and eventually reach juniors in BC. In my opinion it’s just a matter of time until the last few miners realize they’ve locked up the last of the world’s reserves of copper amongst themselves. When they do it’s going to be a mad scramble to lock up British Columbia’s copper resources.

After all, it’s the juniors who currently own BC’s future mining reserves.

In a breaking bit of good news Business in Vancouver recently reported that B.C. is exploring the possibility of building a copper smelter and refinery as critical minerals increasingly become a national security issue.

The federal and B.C. governments announced Wednesday they are launching a Request for Information (RFI) to assess the viability and potential locations for a copper processing facility in Western Canada.

The RFI, which runs until Jan. 28, 2026, will examine the feasibility and siting options for a facility that could include a smelter and a refinery.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.