Data centers: Gluttons for power, water and minerals Part I – Richard Mills

2025.12.21

Data centers are growing rapidly in size and number, leading to a significant increase in their consumption of energy, water and minerals. This expansion is largely driven by the increasing demand for Artificial Intelligence (AI), cloud computing and digital services.

What are data centers?

According to Yes Energy, Data centers store, process, and manage large volumes of digital data and computing resources. Data centers house the necessary infrastructure for businesses, organizations, and online services to store and access data, run applications, and ensure reliable and high-speed network connectivity.

The blog notes there are four types of data centers:

- Enterprise: built, owned, and operated by an individual company to meet its specific computing, storage, and networking needs.

Managed services: the company leases the equipment and infrastructure instead of buying it.

- Colocation: the colocation data center hosts the infrastructure, while the company provides and manages the components.

- Cloud or hyperscale: massive, centralized, custom-built facilities operated by a single company, such as Google or Amazon Web Services (AWS).

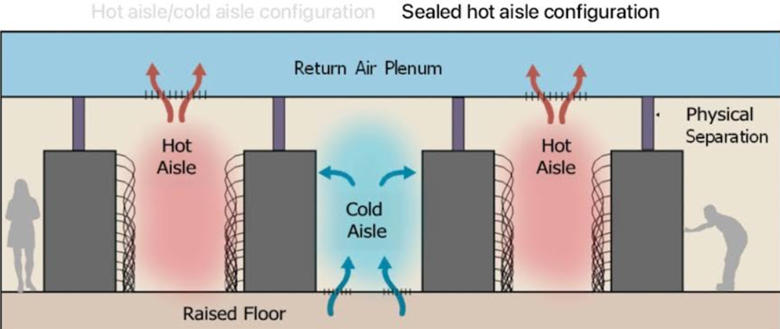

A Stanford University publication describes halls filled with identical rows of hundreds of computer servers arranged in aisles – a “cold aisle” where the server draws in cool air, and a “hot aisle” where exhaust is vented.

Scale of the buildout

Tech companies are plowing billions of dollars into data centers in pursuit of revolutionary advances in artificial intelligence. There are both positives and negatives in this. The negatives, as mentioned at the top, are the straining of power grids, water resources, and potentially, even financial markets — the latter discussed in a section below.

More positively, Bloomberg notes The visible manifestations of this revolution-in-progress are the vast, windowless buildings that are springing up across the world to handle AI workloads. Where a “big” data center was once roughly the size of a football field, some of the new AI facilities will cover an area comparable to Central Park in Manhattan. The investments required are so large that they’re giving a significant boost to the US national economy.

The International Energy Agency says investment in data centers is expected to reach US$580 billion this year, surpassing the $540 billion on the global oil supply, leading some to say that “data is the new oil.”

Barclays estimates that Meta, Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Oracle will have roughly $390 billion in combined capex this year, a 71% year-over-year rise with more on the way. (Axios)

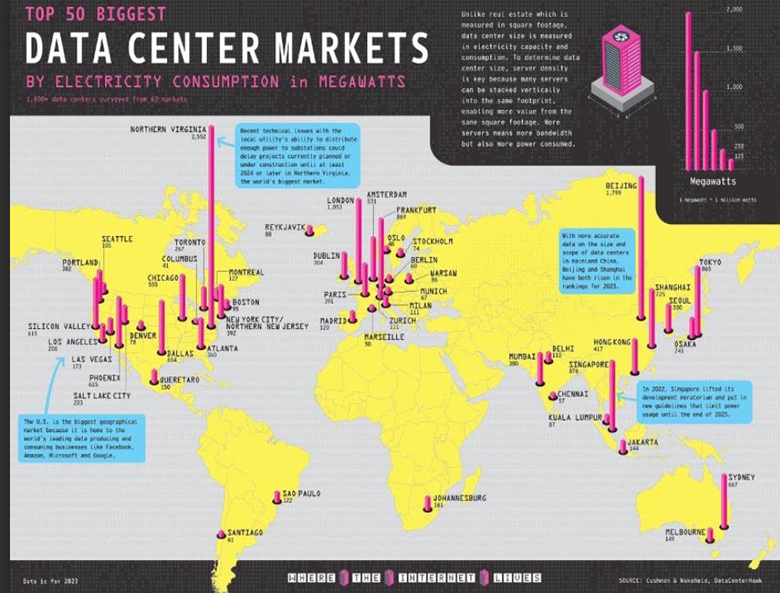

Data center growth is highly concentrated geographically. More than 85% of new data center capacity additions over the next 10 years are expected to be in the United States, China and the European Union, according to the IEA.

The US currently accounts for roughly 40% of the global data center market.

A McKinsey analysis finds the United States is also expected to be the fastest-growing market for data centers, from 25 gigawatts of demand in 2024 to more than 80 GW of demand in 2030.

This growth is fueled by the continued increase in data, compute and connectivity from digitalization, and cloud migration, as well as the scaling of new technologies—the most important of which is AI.

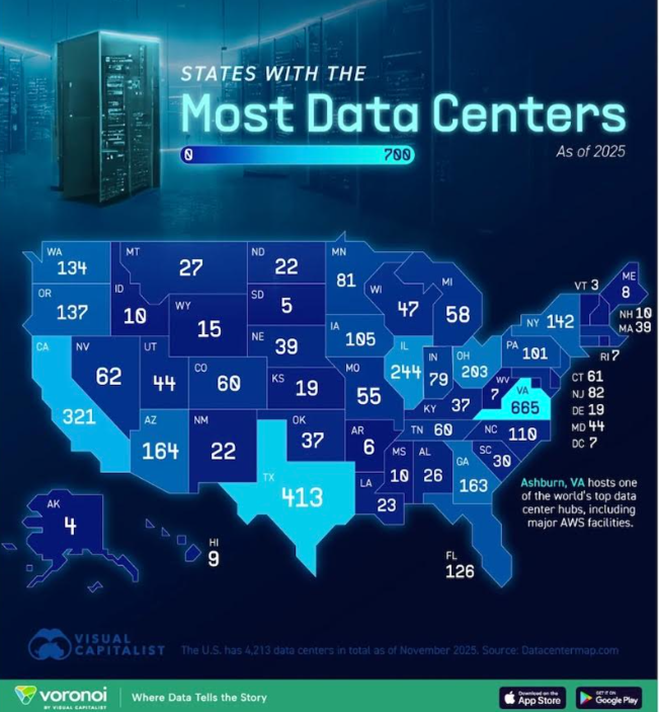

Visual Capitalist created a map of the US states with the most data centers in 2025. The key takeaways are that Virginia dominates the US data center infrastructure with more than 600 facilities; and that network effects, cheap power and cloud hyperscaler clusters make Northern Virginia the most critical internet hub.

Yes Energy says the Northern Virginia data center market is the largest in the world, with nearly 300 facilities. The state hosts massive deployments from all major hyperscalers including Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, Meta and Oracle Cloud.

Data centers in the region are estimated to handle more than one-third of global online traffic.

The Visual Capitalist map shows that Texas ranks second behind Virigina’s 664 data centers with 413, “driven by abundant land, competitive electricity costs, and major cloud deployments in Dallas, Austin, and San Antonio.”

California follows with 321 facilities, “supported by long-standing tech ecosystems in Silicon Valley,”, while Illinois, Ohio, Oregon and Washington have become important secondary hubs.

Data center bubble?

So many data center requests have inundated Texas that some energy experts see a bubble forming.

CNBC reports that cheap land and cheap energy are combining to attract a flood of data center developers to the state.

Speculative projects are clogging up the pipeline to connect to the electric grid, making it difficult to see how much demand will actually materialize, they say. But investors will be left on the hook if inflated demand forecasts lead to more infrastructure being built than is actually needed.

In other words, there is a risk of stranded assets.

The cost of building new power plants to serve the Texas electric market is generally borne by investors, shielding consumers from higher electricity prices. This compares to places like mid-Western and mid-Atlantic states where the grid operators buy power generation years in advance with the burden falling on ratepayers. In Illinois, for example, residential electricity prices increased about 20% in September.

While more than 220 gigawatts of power have asked to connect to the Texas grid by 2030, and more than 70% of those projects are data centers, over half of them (about 128 GW) have not submitted studies for ERCOT, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas.

“We know it’s not all real. The question is how much is real,” said Michael Hogan, a senior advisor at the Regulatory Assistance Project, which advises governments and regulators on energy policy.

The huge numbers in Texas reflect a broader data center bubble in the U.S., said Hogan, who has worked in the electric industry for more than four decades, starting at General Electric in 1980.

“As with everything else in Texas, it’s an outsized example of it,” he said.

If all 220 GW of projects were to materialize, it would be more than twice the Lone Star State’s record peak demand this year of around 85 GW, said CNBC, quoting former ERCOT watchdog Beth Garza. “There’s not enough stuff to serve that much load on the equipment side or the consumption side,” said Garza.

AI companies overleveraged

Continuing on the financial side of things, there is a real risk that tech companies are issuing too much debt, posing a potential threat to the financial system and the broader economy.

Fortune magazine reports that, even after adjusting for inflation, tech companies are issuing more corporate bonds than during the dot-com boom of the 1990s.

The 10 largest AI companies, including Meta, Amazon, Nvidia and Alphabet, will issue more than $120 billion this year, Moody’s economist Mark Zandi wrote in a LinkedIn analysis last week.

He noted that the dot-com era was different because internet companies didn’t carry a lot of debt; instead, they were funded by stocks and venture capital.

“That’s not the case with the AI boom,” Zandi added.

Credit market have served as a barometer of rising risk in past technology buildout cycles, states the Wall Street Journal in a recent piece pointing out that Bond traders are showing signs of indigestion over the tens of billions of dollars they lent this fall to large tech companies, or hyperscalers, to pay for new artificial intelligence infrastructure. Mounting concerns of a potential AI bubble kicked into overdrive after Oracle disclosed last week much higher-than-expected spending on costly chips, networking equipment and other capital expenditures.

Despite its massive potential, traders are growing nervous about the future of AI, with the entire US tech sector selling off this week following a report that Oracle’s $10-billion data center is in jeopardy.

Sources told the Financial Times, via Business Insider, that talks to build the data center have stalled due to concerns about debt and spending.

The FT reported that Blue Owl Capital, a significant financial backer, wouldn’t back the data center to be located in Michigan.

Financial blogger Quoth the Raven sees the decision as “an important inflection point in the AI infrastructure boom.” According to a QTR piece provocatively titled, ‘This Is What It Looks Like When Shit Hits The Fan’,

Blue Owl walking away from this deal is, in my view, one of the clearest signs so far that the AI infrastructure build-out may be running into real financial constraints.

This wasn’t a speculative startup or an untested operator. Blue Owl has helped make Oracle’s AI expansion possible by absorbing risk that public markets and balance sheets were reluctant to carry directly. If that support is now being reconsidered, it implies that something fundamental has shifted. At a minimum, it suggests that the margin for error is shrinking fast…

To me, this development fits closely with concerns I’ve been outlining for several months. In earlier pieces like “Credit Crash in AI Names” and “Limbo,” I argued that the AI infrastructure boom appeared to be transitioning from being largely self-funded to increasingly debt-funded, and that credit markets seemed to be noticing this shift before equity markets did…

What makes the current setup particularly fragile, in my opinion, is how tightly AI, credit, and private equity are intertwined. AI narratives justify massive spending. Credit markets fund it. Private equity absorbs and redistributes risk. Accounting keeps the optics clean. Equity markets reward the story. That works until it doesn’t. When several of those supports start to wobble at the same time, things can unravel faster than expected.

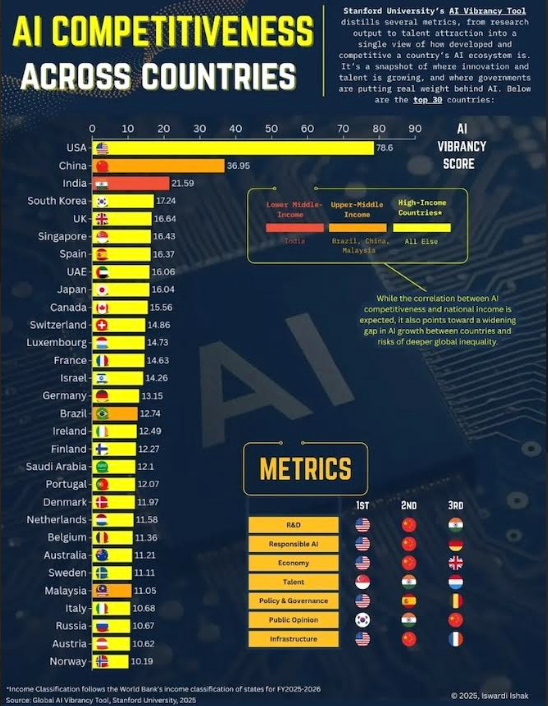

Global AI competitiveness

Still, the United States leads global AI competitiveness by a wide margin, with China and India following, according to a recent infographic and writeup by Visual Capitalist.

Economies like South Korea, the UK, Singapore and Spain also scored highly.

The infographic used Stanford University’s “AI Vibrancy Tool” to measure how vibrant a country’s AI ecosystem is. The tool used 42 indicators across eight “pillars” including research, economic competitiveness, infrastructure, policy & governance, and public opinion.

“The United States tops the ranking thanks to its dominance in private investment, academic research, and AI startup activity. Its homegrown tech giants and prolific research institutions drive a significant share of global AI innovation,” states infographic creator Iswardi Ishak.

Energy consumption

Data centers are inherently energy-intensive, and their power consumption is projected to double globally by 2030, reaching around 945-980 terawatt-hours (TWh) annually. In some countries like the US, they could account for up to 12% of total electricity consumption by 2030, straining existing power grids. (AI Overview).

Bloomberg says The largest AI data centers are expected to gobble up at least a gigawatt of electricity, enough to power roughly 750,000 US homes. If data centers were a country, by 2035 they would be the fourth-largest consumer of electricity after the US, China and India, according to BloombergNEF estimates.

BloombergNEF also sees power demand from data centers reaching 106 gigwatts by 2035, which is a 36% upward revision from its April outlook, per Axios. One gigawatt can power 750,000 to a million homes.

While only 10% of data centers exceed 50 MW of capacity, most in development are higher than 100 MW.

Other key points from Axios regarding data center power demand:

The Energy Department and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission are working on a new policy to speed up data center grid connections.

The tech and data center industries are scrambling to find new power sources — including re-start of shuttered plants — to supply electricity for training and using AI models.

The boom is bringing fears of localized grid strains and wider power system problems as overall energy demand rises.

“These pressures point to an inflection moment for US grids: the desire to accommodate AI-driven load without undermining reliability or driving up power costs,” BloombergNEF said in a summary of the report.

US states are having to reshape their electricity infrastructure to accommodate data center growth. In Nevada, data center developer Switch is on track to consumer one-third of the state’s power; the company is the biggest client of NV Energy.

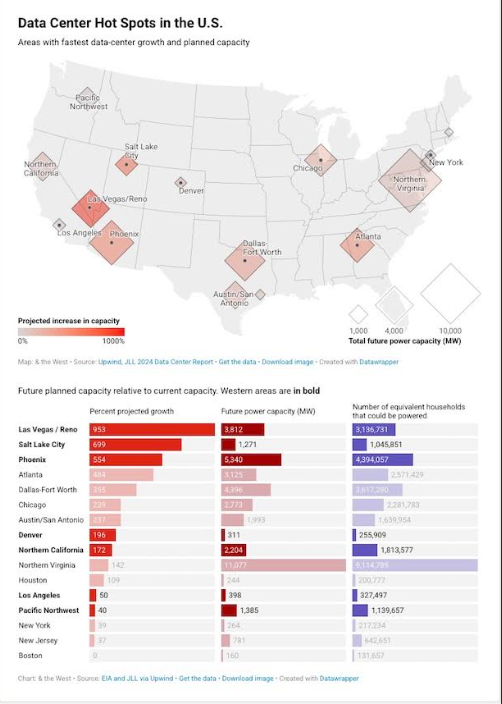

Between now and 2030, Texas is expected to add 62% to its grid, the equivalent of bolting on California to Texas.

In Arizona, data centers use 7.4% of the state’s power, in Oregon 11.4%, according to Visual Capitalist.

What makes data centers such gluttons for energy?

Yes Energy says it’s due to the enormous scale and complexity of their operations.

This is mainly because they provide power and cooling for numerous servers and networking equipment responsible for processing and storing massive amounts of data.

Due to the increasing use of cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI), and data-driven applications, data centers are increasingly using more electricity. And since data centers operate 24/7, they need a constant supply of energy.

The energy required for cooling can account for a significant portion of a data center’s overall energy consumption. As servers process data, they generate heat, and effective cooling is necessary to prevent overheating and to ensure the reliability of the equipment. Air-conditioning systems or liquid cooling (i.e., water) are employed to manage the thermal load.

Data centers are one of the most energy-intensive types of buildings, consuming 10 to 50 times the energy per floor space of a typical commercial office building. Collectively, these spaces account for approximately 2% of the total US electricity use.

According to McKinsey, demand (measured by power consumption to reflect the number of servers a data center can house) is forecasted to grow approximately 10% each year through 2030, reaching 35 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, up from 17 GW in 2022…

In 2023, for example, Northern Virginia data centers had a combined power consumption capacity of 2,552 MW — four times the capacity of the Dallas (654 MW) or Silicon Valley (615 MW) markets.

As a result, the Northern Virginia data centers are driving significant and unexpected electricity demand. Loads have increased at an unprecedented rate, leading to an immediate need for large-scale transmission infrastructure upgrades.

In a September article, McKinsey says that to keep pace with current adoption of data centers across the US, their power needs are expected to be about triple current capacity by the end of the decade, i.e., from between 3 and 4% of US power demand to between 11 and 12%.

Providing the more than 50 GW of additional data center capacity needed by 2030 would require an investment of more than $500 billion in data center infrastructure alone. This during a period when US grid infrastructure is already stretched and failing in some places.

Without this investment, the potential of AI will not be full realized, McKinsey warns.

Generative AI — which involves the application of algorithms, systems, and models that create or generate new content, ideas, or designs without direct human involvement — could create between $2.6 trillion and $4.4 trillion in economic activity, McKinsey estimates, but achieving only a quarter of this potential by the end of the decade would require 50-60 GW of additional data center infrastructure in the US alone.

Meeting this demand will require considerably more electricity than is currently produced in the United States. This spike in electricity needs is unprecedented in the United States, where power demand in the aggregate has barely grown since 2007. Data center load may make up between 30 and 40 percent of all net new demand added until 2030…

Constraints across the power value chain that may hinder progress include physical limits on node sizes and transistor densities; longer lead times, a shortage of compute availability, and a shortage of electrical trade workers.

According to McKinsey’s research, time to power is the biggest consideration for data center operators when building new sites.

[As] access to grids has declines, timelines for investing in and further building out grids for regulated utilities have become longer than the development cycle of data centers.

Notably, power unavailability in most markets is driven by limitations in interconnecting to the transmission grid, rather than an inability to generate the power.

On an operational level, it’s still not clear why data centers require so much power. Technology Review took a stab at answering that question and came up with a number of scenarios.

It starts by noting that the resources required to power the AI revolution are staggering, and the world’s biggest tech companies have made it a priority to harness more energy. Meta and Microsoft, for example, are looking to build new nuclear plants. The Strategic Initiative announced by OpenAI — creator of ChatGPT — and President Trump aims to spend $500 billion, more than the Apollo space program, on building 10 new data centers. The power requirements for this would be more than the total power demand of New Hampshire.

Apple plans to spend $500B on manufacturing and data centers in the US over the next four years, while Google expects to spend $75B on AI infrastructure alone in 2025.

A couple more points before we get into the nitty gritty. Technology Review says that by 2028, more than half of the electricity going to data centers will be used for AI. At that point, AI alone could consume as much electricity per year as 22% of US households.

Examples of energy usage

So how do AI centers actually work and why do they consume so much power? Technology Review explains it best:

Before you can ask an AI model to help you with travel plans or generate a video, the model is born in a data center.

Racks of servers hum along for months, ingesting training data, crunching numbers, and performing computations. This is a time-consuming and expensive process—it’s estimated that training OpenAI’s GPT-4 took over $100 million and consumed 50 gigawatt-hours of energy, enough to power San Francisco for three days. It’s only after this training, when consumers or customers “inference” the AI models to get answers or generate outputs, that model makers hope to recoup their massive costs and eventually turn a profit…

As conversations with experts and AI companies made clear, inference, not training, represents an increasing majority of AI’s energy demands and will continue to do so in the near future. It’s now estimated that 80–90% of computing power for AI is used for inference.

All this happens in data centers. There are roughly 3,000 such buildings across the United States that house servers and cooling systems and are run by cloud providers and tech giants like Amazon or Microsoft but used by AI startups too. A growing number—though it’s not clear exactly how many, since information on such facilities is guarded so tightly—are set up for AI inferencing.

At each of these centers, AI models are loaded onto clusters of servers containing special chips called graphics processing units, or GPUs, most notably a particular model made by Nvidia called the H100.

This chip started shipping in October 2022, just a month before ChatGPT launched to the public. Sales of H100s have soared since and are part of why Nvidia regularly ranks as the most valuable publicly traded company in the world.

Other chips include the A100 and the latest Blackwells. What all have in common is a significant energy requirement to run their advanced operations without overheating.

A single AI model might be housed on a dozen or so GPUs, and a large data center might have well over 10,000 of these chips connected together.

Wired close together with these chips are CPUs (chips that serve up information to the GPUs) and fans to keep everything cool…

Depending on anticipated usage, these AI models are loaded onto hundreds or thousands of clusters in various data centers around the globe, each of which have different mixes of energy powering them.

They’re then connected online, just waiting for you to ping them with a question.

AI companies are notoriously secretive of what happens within their data centers. Factors like which data center in the world processes your request, how much energy it takes to do so, and how carbon-intensive are the energy sources used, tend to be known only by the companies that run the models.

Fortunately, there are open-source models that have special tools to measure how much energy the H100 GPU requires for a given task. Using these open-source models, Technology Review gave the following examples of power usage per AI query:

Text models, where you type a question and receive back a response in words, required about 57 joules per response, the equivalent of riding an e-bike about six feet, or running a microwave for a tenth of a second.

The Llama 3.1 405B model has 50 times more parameters which mean better answers but require more energy. On average, this model needed an estimate 6,706 joules per response, enough to carry a rider about 400 feet on an e-bike or run a microwave for eight seconds.

Generating images through AI models work with a different architecture called diffusion. Generating a standard-quality image of 1025 x 1024 pixels with Stable Diffusion 3 Medium, the leading open-source image generator with 2 billion parameters, required about 1,141 joules of GPU energy.

Improving the image quality by doubling the number of diffusion steps to 50 just about doubles the energy required, to about 4,402 joules. That’s equivalent to about 250 feet on an e-bike, or around five and a half seconds running a microwave.

Making high-fidelity videos with AI is now possible. Using the new version of open-source model CogVideoX, made by a Chinese start-up, uses more than 30 times more energy than the older version on each five-second video. That’s about 3.4 million joules, over 700 times the energy required to AI-generate a high-quality image — the equivalent of riding 39 miles on an e-bike or running a microwave for an hour.

Technology Review gives one more example of AI energy usage: A person running a charity marathon asks the model 15 questions about the best ways to fundraise for the event. The person then makes 10 attempts at creating an image for a flyer, before deciding on one, and three attempts at a five-second video to post on Instagram. All of these AI queries would use about 2.9 kilowatts, enough to ride over 100 miles on an e-bike (or around 10 miles in an EV) or run the microwave for over 3.5 hours.

Extrapolating these energy measurements out to a larger data set shows some alarming stats. ChatGPT is now the fifth most visited website in the world. In February, AI research firm Epoch AI estimated how much energy is used for a single ChatGPT enquiry — about 1,080 joules. A billion enquiries per day would mean over 109 gigwatt-hours of electricity, enough to power 10,400 US homes for a year. Adding images would mean an additional 35 gigawatt-hours, enough to power another 3,300 US homes for a year.

As for future AI proliferation and energy demand, a report published by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that data centers in the US used around 200 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024, roughly what it takes to power Thailand for a year.

Researchers estimate that by 2028, the power going to AI purposes will rise to between 165 and 326 terrawatt-hours per year, more than all electricity currently used by US data centers for all purposes. That’s enough to power 22% of US households each year, and it would generate the same emissions as driving over 300 billion miles — over 1,600 round trips to the sun from earth.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.