A recession is coming, buy gold explorers with scale

2019.03.22

Mining has a well-worn adage, “grade is king”. While that may be true in some situations, it’s the opposite in others, where a lower-grade deposit can actually reap more profits.

This is especially true if the mine is underground, where the high costs of labor and specialized mining equipment, plus the difficulty mining veins – digging deep requires a lot of material to be blasted and moved – means that margins are often squeezed to the breaking point. A steep, sustained drop in the gold price can spell disaster even for a high-grade underground gold mine like Pretium’s Brucejack in northern BC (average grade 14.1 grams per tonne). It’s just too expensive to make a profit in a high-cost, low-price environment.

In contrast, a low-grade deposit with a lot of scale, or scalability due to expansion potential, can easily outperform a high-grade beauty, long-term. The lower grades are made up for in tonnage, and depending on the operation, processing costs. Oxide gold ore can be heap-leached fairly cheaply, for example. This combination of factors – low grade + scale + low cost – can often withstand a price downturn.

It’s a bit like the tortoise and the hare – “slow and steady wins the race”.

This article will take a closer look at low-grade versus high-grade gold mines, placed into today’s macro-economic climate, which is very bullish for gold.

Attention! Yield curve inversion!

Smart gold investors follow the Treasuries market. Why? Because they are backed by the US government, US Treasury bills are the safest financial instrument out there, so the movements of the T-bond market are a strong indication of how investors feel about the US economy. This in turn affects the US dollar and the price of gold. Gold and the dollar move in opposite directions: As the dollar rises, gold goes down, and vice versa. This is gold investing 101.

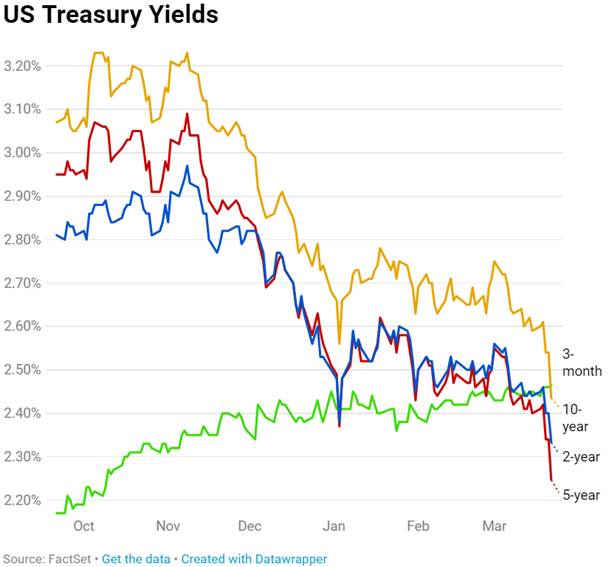

10-year Treasury yield falls to 14-month low, signaling possible trouble with economy

Gold investing 201 is watching the yield curve. Yields are the amount of interest a T-bond – which ranges in maturity from one month to 30 years – will pay. As bond prices rise, yields fall. Normally the “yield curve” slopes upward, because the longer the term, the more interest the T-bill must charge to attract investors.

The more interesting thing to watch is when the yield curve starts behaving out of the norm, like currently. If investors think the US economy will perform better in the short term than long term, short-term yields (say one month to two years) increase more than multi-year or multi-decade T-bills. For economic forecasters, this is a bad sign. It means that more T-bond market investors believe that the economy is slowing down. They would prefer to park their money for the time being, to wait it out and see what happens. They don’t want to be stuck in a long-term investment. It’s a bit like choosing a one-year or variable rate mortgage versus a five-year term, if you’re wary of interest rates going up.

Anyway, this is just background to understand what happened on Wednesday, March 20. Following the US Federal Reserve’s decision not to raise interest rates any higher in 2019, the yield curve inverted. (well to be more precise, the yield curve between the 3-month and 2- and 5-year bonds inverted) Yields for the 3-month bond rose to 2.478%, versus a respective 2.39% for the 2-year and 2.31% for the 5-year. These don’t seem like large differences, but it’s all about perception.

Meanwhile the yields on two key long-term bonds, 10-year and 30-year, dropped, by a respective 2.519% (-8 basis points) and 2.957%. In fact the 10-year yield plummeted to a 14-month low, showing that earlier fears of a recession, when the yield curve inverted in December, are getting downright scary.

On December 3 the 2-year Treasury yield rose above the 5-year yield (another bad economic sign), and remains at its flattest (a very small difference between the two) since May 2007, CNBC reported.

Check out this link to economic forecasting blog Mish Mash, showing a table of yield curves on December 18 versus March 20. The spread between the 3-month and the 10-year yields is just 8 basis points. The 10-year bond dropped that much in one day this week! In other words, this is very close to an inversion. The 10-year and 2-year rates have already inverted, at 2.402% for the 2 and 2.541% for the 10.

Doves beating hawks

Not only is the Fed not going to raise interest rates, which would have shown confidence in the US economy, it’s going to end the so-called “runoff of bonds from its balance sheet”. The central bank was doing this in order to reduce the $4.3 trillion in purchases of Treasury bills and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) it racked up through quantitative easing. In other words, it’s been reducing the size of its balance sheet by not replacing maturing Treasuries and MBS.

When Fed chair Jerome Powell said on Wednesday the runoff would end, the signal to investors was that the Fed would start buying bonds again. This increased demand for bonds, which hiked their prices, and lowered yields. The Treasury yield is the first mover in setting interest rates and mortgage rates. For example the US 30-year mortgage rate is usually one or two percentage points above the yield on the 30-year T-bond.

After Powell’s dovish move, mortgage rates fell, from 4.40% to 4.34%, which is quite a drop from the 5% it hit in November. Mortgage rates are a key indicator of how the economy is doing because of their connection to home sales. Falling mortgage rates encourage spending on houses, typically a family’s biggest-ticket item, so the central bank is implicitly trying to heat up the economy.

This is in contrast to the Fed’s more hawkish policy since 2015, when it started raising rates as the economy recovered from the 2008-09 recession. The 2015 raise was the first time that happened since 2006; it’s been gradually raising interest rates from the near 0% level they had been at since 2008, to 2.5% in December 2018. Now the Fed has backtracked on further increases even though it had been suggesting three more in 2019. The doves are beating the hawks.

Trump’s low dollar and gold

The question is why? Economist Nouriel Roubini, who teaches at New York University’s Stern School of Business, provides some explanations.

According to official Fed policy, the interest rate freeze this year is due to concerns about growth. It now expects the US economy to grow by just 2.1% this year versus 2.3% it predicted in December. This is not so much due to problems with the US but problems with its trading partners. Europe is already in recession, who knows what’s going to happen to the UK after it finally cuts its ties to the European Union, and China and Japan are slowing. When America’s main customers are hurting, so is the US.

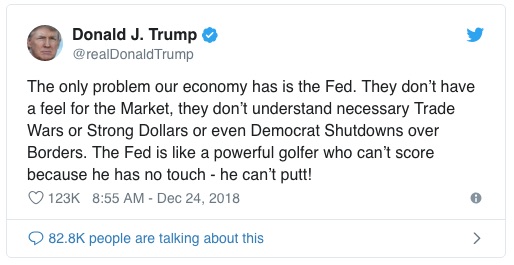

There is something to this explanation of the Fed’s volte-face, but we don’t think it’s the real reason. Give you a hint: it rhymes with bump and lump. Donald Trump has been railing against Fed chair Jerome Powell for months, over his hawkish rate stance. See the tweet below Trump fired off in December after the Fed raised rates.

And the White House disagrees with the Fed’s assessment of economic growth predicting in its 2020 budget proposal an economy growing at 3.2% in 2019.

Why does Trump want low interest rates? Because he wants a low dollar, to counter the trade deficit he campaigned on beating.

In fact the opposite has happened. The buck gained against a basket of other currencies (US dollar index – DXY), rising from April until December 2018.

What kept the dollar high? It was mostly the purchase of US Treasuries, a safe haven in response to lots of global uncertainty, including the stock market correction last fall and Brexit. That increased global demand for US dollars. The dollar was also lifted by the Fed raising interest rates.

This was the opposite of President Trump’s plan to keep the dollar low, in order to make exports cheaper and improve the widening trade deficit.

According to the US Department of Commerce, the country’s trade deficit was $59.8 billion in December, the widest it’s been in a decade, and $891.3 billion for 2018, the biggest annual trade gap in goods (difference between goods imports and exports) ever.

Trump wants to bring jobs back to the US after many were exported abroad to take advantage of lower labor costs, and therefore rebuild the US manufacturing sector. A low dollar would goose exports and reduce imports, thus narrowing the trade deficit.

For more on this read our Why the record US trade deficit is good for commodities

So far this year the dollar has been up and down, neither helped by the US-China trade war, which has seen US exports like cars and soybeans fall, nor hindered by the December rate increase.

The question is, will Trump keep hammering away at the trade deficit, by returning to the low-dollar policy he favors? It certainly appears likely.

The Trump Administration has succeeded in pressuring the US Federal Reserve from backing off further increasing interest rates, which would push up the dollar. In fact, there is now talk of even lowering rates. Former Fed chair Janet Yellen said so when asked for her thoughts on whether the central bank will pursue a tight or loose monetary policy this year.

Interviewed on CBNC, Yellen said weakened economies in China and Europe are a threat to the strong US economy. If that continues, a rate cut might be in the cards.

“Of course it’s possible. If global growth really weakens and that spills over to the United States where financial conditions tighten more and we do see a weakening in the U.S. economy, it’s certainly possible that the next move is a cut,” she said. “But both outcomes are possible.”

A weak dollar usually means stronger commodities prices. Because the USD is the reserve currency and commodities are traded in dollars, the value of the dollar is of crucial importance in determining the value of the commodity in question.

For gold, a weak dollar usually causes a rise in the gold price. We know that negative real interest rates (interest rates minus inflation) are bullish for gold. That would occur if the rate of inflation goes above interest rates. We’re not there yet, but if the Fed does cut rates and there is another QE, which is really printing money to buy bonds, we could be looking at another up-leg in the gold price.

Gold jumped to a near three-week high on Wednesday after the Fed rate freeze decision. A panel of 22 gold analysts surveyed by Focus Economics sees the precious metal rising $30 an ounce to average $1,350/oz a year from now.

Analysts at the World Gold Council also weighed in on the price, stating that historically, gold tends to do well when the Fed switches from a tightening (raising rates) to a neutral stance, although gold bulls may have to wait a few months.

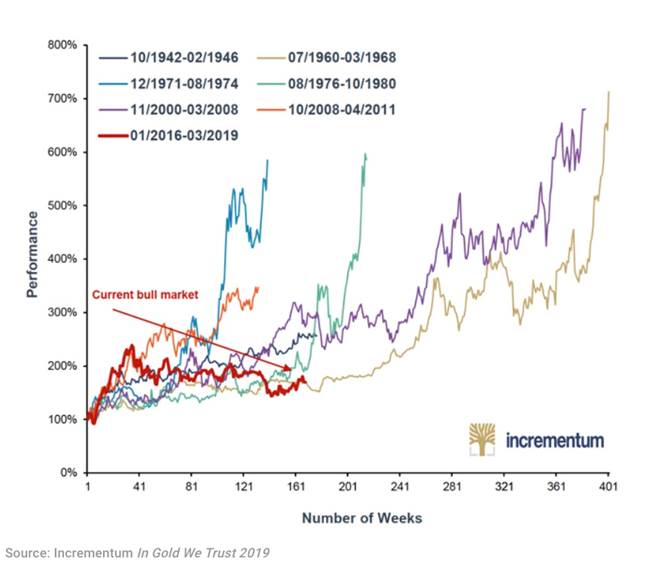

According to Incrementum’s 13th annual compact In Gold We Trust report released this week, the current uptrend in gold stocks is relatively weak, leaving “plenty of upside potential” said MINING.com, quoting from the report.

If we assume that the gold price continues to do well, and it’s not a bad bet, considering the doves at the Fed are now in charge, the best leverage against a higher gold price is an investment in junior gold companies.

When a gold junior drills a discovery hole, the stock can pop by 100, 200, 300 percent. Of course timing is crucial, and volatility is high, but that’s part of the fun…

Obviously, one must choose carefully from the lengthy list of companies all hoping to hit the motherlode. Considering only one project in a thousand becomes a mine, the odds are against you. But there are tried and true criteria. Along with the management team, jurisdiction, nearby infrastructure and a tight share structure, I focus a lot on grade and scale.

The market loves high grade, and so do we (one of our stocks, Aben Resources (TSX-V:ABN) rocketed 138% last summer after hitting jewelry-box-style mineralization), but it’s not the be all end all, as mentioned at the top.

Learn to love low grade

The best example of low-grade success is Nevada’s Carlin Trend. Carlin-style deposits contain disseminated gold, meaning the gold is microscopic but spread widely throughout the orebody. The gold is also near-surface and oxidized, meaning it is amenable to heap-leaching.

Loading the ore onto a heap leach pad and irrigating the pile with cyanide is one of the least expensive (the only cheaper method is gravity separation) forms of gold processing. The technology, which started in Nevada, was a major breakthrough – it put Nevada on the map as the most important state for gold mining.

According to the US Geological Survey, if Nevada was a country, it would be the world’s fourth-largest gold producer.

Barrick’s Cortez mine complex personifies the idea that scale trumps high-grade.

The mine actually consists of the Pipeline open pit and Cortez Hills, mined via open pit and underground. Between 1969 and 2015 Cortez produced 20.010 million ounces, but it’s far from done. The most recent technical report shows 11.2 million ounces of proven and probable reserves, at a lowly 1.83 grams per tonne.

Compare this to the 10 highest-grade gold mines in the world according to this 2017 report – 4.5 to 7.6 g/t open pit, and 15.2 to 21.5 g/t underground.

Barrick is working on two major expansions at Cortez. The Deep South Project has 1.7 million ounces in reserves, and once in production by 2022, would add another 300,000 ounces a year. Barrick also has a greenfield discovery six kilometers from Cortez Hills. The Goldrush deposit has another 8.6 million ounces of measured and indicated resources. Cortez is one of those mines that keeps on giving, and at around $520-$550 per ounce all-in sustaining costs, it still makes money despite low grades.

Another example of a low-grade Nevada operation is SSR Mining’s Marigold mine. At an ultra-low-grade 0.46 g/t, Marigold is a high-margin producer because since 1989, it’s been a run-of-mine operation. The blasted ore goes directly onto the leach pad, without crushing or grinding, saving significant costs. In the third quarter of 2018 Marigold reported AISC of $965/oz, against a $1,207/oz gold price.

Nova Scotia had always mined its gold underground up until Atlantic Gold proved it was possible to make a profit from a surface operation. Its Moore River Consolidated (MRC) project has a 1.5 g/t grade but a very low strip ratio (0.76:1), allowing the company to save on earthmoving. The 200,000-ounce operation has an AISC of $528 an ounce, versus $1,250/oz gold, netting a healthy $717/oz profit. Half of the gold is recovered by extremely low cost gravity separation and the rest by heap leaching.

The Yukon is a third jurisdiction that proves high-grade isn’t always king. The site of the Klondike Gold Rush has yet to produce a mine, but its first one is under construction. Victoria Gold’s Eagle mine has an average grade of just 0.67 g/t but its 4 million ounces of measured and indicated gold gives it impressive scale.

Goldcorp’s Coffee project, which it purchased from Kaminak Gold for $520 million, is no slouch either. Like Eagle the grades are low, just 1.4 g/t, but its 2.1 million ounces of probable reserves were no doubt what clinched the deal with Goldcorp.

Conclusion

High-grade gold mines are like the girl you ask to dance, but a low-grade deposit is the one you bring home to mom. High gold grades are what excites the market, but it’s scale that gives a mine longevity, making the high capital expenditures worth it.

The US Federal Reserve has indicated no more rate hikes this year. The inverting yield curve is flashing “R” for recession, an environment that gold tends to do well in. Even if there’s no recession, and we hope there isn’t, lower rates will weigh the dollar down, pushing commodities up, including precious metals.

Now is a good time to be looking at gold explorers with size on their side. The gold price hasn’t yet enjoyed the run it did last year around this time, but the economic fundamentals are setting up nicely as companies map out summer exploration programs.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.