Saving our Canadian bacon

2018.12.30

For the Trudeau haters out there, this was the moment they’d all been waiting for: a vicious rebuke by a high-ranking US official. It happened after the G7 leaders’ summit in June, when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau criticized US President Donald Trump during the concluding press conference.

Trump had just departed for Singapore, where he was meeting the North Korean leader, when Trudeau told reporters that aluminum and steel duties against Canada were insulting and that Canada would fight them “dollar for dollar”.

The problem was, that’s not what Trudeau told Trump when they spoke during the summit.

“There’s a special place in hell for any foreign leader that engages in bad faith diplomacy with President Donald J. Trump and then tries to stab him in the back on the way out the door,” trade adviser Peter Navarro told Fox News. Senior White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow piled on, calling what was said during the press conference “a cheap shot”.

Dealing with the United States has always been touchy for Canada’s top politicians, especially when it comes to trade. It’s simply a matter of scale. The United States has 10 times the population of Canada. We want market access, but we don’t want to be bullied. On foreign policy, we depend on the United States and its powerful military for protection, but we don’t want that to influence our policies with other countries. It’s the classic “middle power” dilemma. Culturally, we share many things with the United States – movies, music, TV shows, a common language, food, travel destinations, etc. – but we don’t want to be Americanized. This sensitivity to being engulfed by American culture is of course most pronounced in Quebec, which fears cultural assimilation will mean the death of Quebecois culture.

The Canada-US relationship is best symbolized by how the Canadian Prime Minister and US President get along. We look on with interest, amusement, and sometimes alarm, at how they interact.

Perhaps the most stark example of how this dynamic can shift was the “bromance” between Barack Obama and Justin Trudeau that became much less familiar when Trudeau was forced to deal with Donald Trump. Many predicted sparks would fly immediately – the battle-hardened, baby-boomer business tycoon clashing with the younger, effete, liberal-minded Trudeau – but it took a few months for the relationship to gel.

At first it seemed the two would get along, surprisingly, with Trump calling Trudeau “a great guy” and Trudeau mastering Trump’s odd handshake. But when Trump refused to exclude Canada in a trade war and insisted on fulfilling a campaign promise to re-negotiate NAFTA, a chill descended on what is Canada’s most important leader-to-leader relationship.

Of course it was Trudeau’s smarter, more statesmanlike though insufferably arrogant father who famously said, “living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly or temperate the beast, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.”

The latest “twitches” from the United States, felt strongly by Canada, are the US sanctions against Iran, and the trade war with China. The two issues became entwined with the arrest in Vancouver of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou. The US accuses Meng of committing fraud to sidestep sanctions against Iran, and has called for her extradition. China calls the arrest “a kidnapping” and has retaliated by taking three Canadians living in China into custody. There’s a lot for Canada at stake, namely, its economic and political relationships with the two most powerful countries in the world.

Canada is also affected by what the United States doesn’t do. When Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered in the Saudi Arabian embassy in Istanbul, the pressure was on to condemn Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman. But Trump, unsurprisingly, has taken a softer tone, preferring not to insult a key Middle Eastern ally and oil producer. Canada has similarly treated bin Salman with kid gloves, for its own reasons.

This article will explain why Canada has for the most part fallen in line with the United States over the Huawei and Khashoggi incidents: it’s to save our bacon.

Huawei

Canada is being forced to do the US’s bidding on what it deems a technological and security threat to the United States. I’m talking about Huawei Technologies, the Chinese telecommunications giant with close ties to the Communist Party.

That’s the view of Jeffrey Sachs, an economist who writes for Project Syndicate.

According to Sachs, the unprecedented arrest of a Chinese executive is an example of the US creating “a new Cold War” in international trade. But it’s Canada that’s having to fight.

Canadian officials arrested Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s 46-year-old CFO and daughter of the company’s founder, at Vancouver Airport, on an extradition request from the United States. She has since been released on $10 million bail and must not leave her Vancouver home.

Why the arrest? US prosecutors say Meng fraudulently deceived HSBC about the level of control Huawei had over a company named Skycom, so that Skycom could do business with Iranian telecoms. She has been charged with conspiracy to defraud banks. However Skycom, a former Huawei subsidiary, has been dissolved and Meng says Huawei sold its interest in Skycom and that she stepped down from its board of directors.

Banks can be held criminally liable if they help move money out of a sanctioned country.

But Sachs says the prosecutors’ argument is thin, considering that HSBC has been slapped hard before for violating US sanctions and money-laundering (in 2012 the bank had to pay $1.92 billion) but is not even under investigation concerning Meng’s arrest.

“I think Canada’s doing the bidding of United States policy that is not well-controlled or well-modulated,” he said in a CBC video interview.

“Maybe Canada’s being used and manipulated, not only vis-à-vis China, but for the United States to try to show anyone: ‘You dare cross us on any business with Iran, you’re going to pay a price.’”

The United States re-imposed sanctions on Iran in August – after a two-year reprieve – and also withdrew from the multilateral nuclear deal with Iran spearheaded by former President Obama.

The United States has had Huawei in its sights for some time. In May the Pentagon banned the sale of Huawei and ZTE phones on military bases, fearing the phones could be used to spy on soldiers. The government has also stopped buying Huawei equipment and will not help any carrier that uses its technology. Verizon and AT&T have backed out of deals to distribute Huawei phones.

In Canada, Huawei already has equipment in the present 4G cellular networks, and the company could be asked to help build the 5G network which is expected to vastly increase Internet speeds. The worry here, and in the US, is that Huawei could use its telecommunications technology to secretly gather intelligence. While Huawei has said it would never do that, Chinese law states that “any organization or citizen shall support, assist and co-operate with state intelligence work.”

The Canadian government is currently weighing the risks of continuing to use Huawei, which is the world’s largest supplier of telecommunications equipment.

The White House says there’s no connection between Huawei’s arrest and banning Huawei from doing business in the States. That’s BS. China and the US are fighting a trade war and there is little doubt the arrest is connected – if not directly. Part of the Commerce Department’s rationale for slapping tariffs on China was to allay concerns over US firms having to surrender intellectual property in order to gain market access to China. Cypersecurity is also a serious issue and Huawei could be a trojan horse. Recently American prosecutors charged two Chinese nationals for economic espionage. They allege the individuals hacked into the US Navy, NASA, the Energy Department and dozens of companies.

The Huawei issue has gotten political – it’s no longer a simple matter of extradition. President Trump waded into the fray by stating he would intervene if it helps the United States to win the trade war. Here Trump has overstepped his authority. Extradition is supposed to be a purely legal process, insulated from politics. If Trump gets involved (and why wouldn’t he, he’s done it with Amazon, CNN and General Motors, Bloomberg points out) to suit his objectives, it’s not only disregarding the rule of law, it could also help Meng, who might say that, if the American President can intervene, why can’t the Prime Minister, to set her free?

One could also argue the US Justice Department is playing politics with the case as well, the Toronto Star editorial board writes:

No one believes China’s courts are free from pressure by the government and the ruling Communist Party.

In the Huawei case, though, we are asked to accept that at a time of high tension between Washington and Beijing, focused on trade but involving a broader struggle for leadership of the world economy, it’s just a coincidence that the American Justice Department picked this moment to ask Canadian authorities to arrest and possibly extradite one of the most senior leaders of China’s premier international technology company.

There’s no connection, says the White House, between the arrest and the fact that Washington has been on a campaign to prevent Huawei from taking a leading role in next-generation 5G communications technology. At stake is who will dominate future global telecom networks, and there’s genuine concern that allowing Huawei to emerge on top would open the door to industrial espionage on a massive scale by a company tightly linked to the top levels of the Chinese government…

Using the law and the court system as part of a political shake-down is the kind of move we might well expect from China itself. Under the Trump administration, sadly, it’s something we can’t rule out much closer to home.

This issue is turning out to be a major test of the relationship not only between Canada and the US, but Canada and China. China has cast a diplomatic frost over the two nations by detaining three Canadians (detainee update). Our government is now warning Canadians traveling to China to exercise caution. Unlike North America, in China no-one has legal rights to fall back on should they be picked up by the police for any reason. Canada wants to negotiate a trade deal with China even though doing so could jeopardize the re-negotiated NAFTA (The partners to the deal are not supposed to ink trade deals with “non-market economies”). Will China engage in trade talks while one of their top executives is technically imprisoned in Vancouver? Unlikely.

So the question is, should Canada refuse to extradite Meng and let her go? Or do what it usually does in these cases – 90% of them actually – and comply with the United States by allowing her extradition? If Meng is convicted in the US, she could face a 30-year sentence or $1 million fine (is there any doubt which she’ll choose?)

It will all come down to the Justice Minister, Jody Wilson-Raybould. The Toronto Star explains the parameters:

Canada’s extradition treaty with the U.S. is pretty clear; if there’s evidence the crime she is accused of in the U.S. would constitute a crime if it were committed on Canada, Canada would ordinarily agree.

There are mandatory grounds for refusing extradition, such as if the person’s already been tried for the offence in Canada; if extradition would violate an individual’s Charter rights to due process, a broad category; or if a prosecution would be for an “improper purpose,” including to prosecute or punish an individual by reason of their race, religion, nationality, ethnic origin, language, or colour, or on other discriminatory grounds.

A minister has discretionary powers to refuse a request; Canada does not extradite to countries that have the death penalty without first obtaining assurances from the other country that it won’t execute the extradited individual.

Technically, then, the minister could refuse to extradite her. But doing so would set a dangerous precedent, offending not only libertarians who fear that legal processes are being interfered with by politicians, but the US president himself.

“[T]he law allows Canada to turn down any request if it is seen as a bid to prosecute a “political offence,” the Star quotes a law professor at Dalhousie University, who describes extradition law as “a weird mixture of law and politics.” However, he adds “It would be unheard of for the minister to say a prosecution on the part of our good friends the Americans was politicized and refuse extradition on that basis.

“That would be like punching Trump, himself, in the nose.”

So what is Canada to do? Extradite Meng, and incur the wrath of the world’s second largest economy and home to hundreds of thousands of the Chinese diaspora, and possibly kill a trade deal that could offset American economic power to boot? Or refuse to do so, and offend the American government and its volatile President?

At Ahead of the Herd we always follow the money, so that is most likely to provide our answer. In 2016 Canada did US$544 billion in trade with the United States; the same year, China exported $48 billion to Canada and imported $41 billion. Remember Trudeau Sr.’s sleeping elephant analogy? If China rolls over on us, it might hurt a little. If the US does, we’ll get crushed. Don’t forget, the United States has yet to rescind its tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum imports, despite the new trade deal signed in September.

Siding with China against the US on Huawei is likely to invite more trade retaliation.

The Khashoggi incident

One of the things about being the largest crude oil exporter, in a world still run by oil, is you get to do certain things with impunity. That includes “taking care of” dissident journalists like Jamal Khashoggi, and being part of a coalition of Arab states that is fighting a civil war in Yemen. The conflict is horrifying in its civilian casualties. According to the UN Commission for Human Rights, Saudi air attacks accounted for almost two-thirds of reported civilian deaths last year. Save the Children estimates at least 50,000 children died, or 130 every day.

This seems like a war worth stopping – an international crisis like the Ethiopian famine or the wars in former Yugoslavia – but you’d be wrong. The West has done nothing to help Yemen, mostly because it’s a proxy war between the Middle East’s two most powerful actors, Saudi Arabia and Iran. Nobody wants to get between these two. Good luck even understanding it. If you’re interested in knowing more, check Al Jazeerah.

The US has a longstanding relationship with Saudi Arabia – basically agreeing to defend the oil-soaked country in exchange for selling oil in US dollars. But Canada has no such obligation. For years our criticisms of the House of Saud for its dismal human rights record (48 people were beheaded in the first four months of this year), have fallen on deaf ears, but that all changed in August when Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland decided to go all Trump and fired off a tweet calling for the release of jailed human rights activists.

Riyadh immediately severed diplomatic and trade ties, then later recalled all of its foreign students. Reuters reported Saudi Arabia’s unusually strong response was likely because it is “emboldened by Washington’s willingness under Donald Trump to de-emphasize rights issues when it comes to its allies” versus his predecessor, Barack Obama. Recall it was Obama who signed the Iran nuclear agreement, to Saudi Arabia’s horror, and Trump that withdrew from it, further solidifying their alliance.

All of this is background for what happened next: the alleged murder of Jamal Khashoggi. While we’ll never know precisely what happened to the late journalist, we do know that the Saudi leadership wanted him gone. In the last year of his life, Khashoggi went into self-imposed exile in the US, from where he wrote a monthly column in the Washington Post criticizing the Saudi government and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, known as MBS.

The grisly killing of Khashoggi (the BBC reports the Saudi public prosecutor saying he was given a lethal injection after a struggle and his body dismembered) prompted just about every leader in the Western world to condemn MBS for it, but it looks like nothing is going to happen. An international incident in October has turned into a nothing burger. The best Canada could do was to freeze the assets of 17 Saudi nationals and prevent them from entering Canada.

Why would that be? Well again, we only need to follow the money. Prime Minister Trudeau said he pressed MBS on the killing while they were at the G20 together in Argentina, but we don’t know how hard he really pushed. What we do know is that Canada has a US$13 billion deal to export armored vehicles to Saudi Arabia. The vehicles would be made by a unit of US Military contractor General Dynamics, London Ontario-based General Dynamics Land Systems.

Suspecting what happened to Khashoggi, Trudeau is now trying to get out of the deal, but the reality is, it would cost a billion dollars to cancel it. Does the Prime Minister really want to make taxpayers eat that? No. There’s also the matter of about 500 production workers at General Dynamics, some of whom would likely be shown the door if that contract gets deep-sixed.

London is only 240 clicks away from Oshawa, where the closure of the GM plant will put 2,500 workers on EI. Combine that with the fact that a federal election is less than a year away, and you know the contract is going ahead.

Then there’s the oil. As protesters were gathering to shout down the Kinder Morgan pipeline proposal this summer, Saudi oil was flowing into the massive Irving Oil-owned New Brunswick refinery. Saudi Arabia is second to the United States for the amount of crude oil imported by Canada. It used to be the fifth largest importer. According to the National Post, in the first six months of 2018, the Irving Oil refinery imported $10 million a day worth of Saudi oil, versus just $3.8 million worth of US oil. The refinery counts on Saudi Arabia for 40% of its crude.

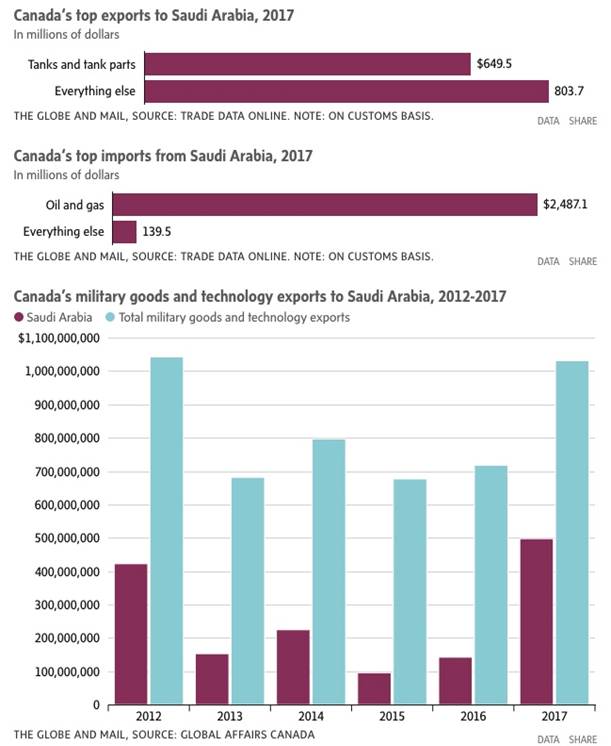

Three graphs from the Globe and Mail are also illuminating. While Canadian politicians complain about Saudi Arabia jailing dissidents and executing homosexuals, we are churning out tanks/ tank parts and buying their oil – lots of it; the National Energy Board estimates 80,000 barrels a day, or 12% of our oil imports. The value of Canadian military goods and equipment exported to Saudi Arabia in 2017 was the most in five years.

How about the United States? The Trump Administration has also turned a blind eye to Saudi transgressions, proving that oil might be thicker than blood. Like Canada, it’s all about weaponry and oil, although these days, it’s less about oil.

In 2017 Saudi oil shipments to America dropped to 1988 levels, due to Saudi Arabia, the leader of OPEC, slashing exports to the United States in 2016 as part of OPEC’s production cuts. With so much domestic shale oil production, the States in no longer dependent on the Kingdom for its oil supplies.

Instead, the trade now is in arms. Saudi Arabia was the first country Trump visited after being elected President in 2016. When he was there, the Saudis agreed to buy $110 billion worth of military equipment. Saudi Arabia is the top buyer of American military hardware; according to the Stockholm Institute, it accounted for nearly a fifth of all US weapons exports over the last five years.

Currently, some of those arms are going to fight the war in Yemen – where the US government has provided intelligence, munitions and midair refueling to Saudi warplanes since the conflict began in 2015, states an article in Time.

The Senate on Dec. 13 passed a resolution calling for an end to US Military support for the Saudi Arabia-led coalition fighting the war, although it could still be vetoed by the Republican-led House of Representatives (until mid-January). According to Time, Saudi lobbyists have spent between $5.8 and $9 million on lobbying Congress this year.

While arms dealing is obviously key, another article, by Project Syndicate, argues the most important aspect of the US-Saudi relationship is that Saudi Arabia provides a bulwark against Iran:

The kingdom has supported proxies in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen to contain Iran’s machinations.

Any steps to hold the Saudis responsible for Khashoggi’s death would force the U.S. to assume responsibilities it is far more comfortable outsourcing.

Understandably though, President Trump chose to focus on the money when explaining why no action would be taken (ie. canceling weapons contracts) against the Saudis for the Khashoggi killing:

“If we foolishly cancel these contracts, Russia and China would be the enormous beneficiaries – and very happy to acquire all of this newfound business. It would be a wonderful gift to them directly from the United States!”

A statement by Trump bragged that Saudi Arabia promised to spend $450 billion in the United States (talk is cheap) including the aforementioned $110 billion. As for Khashoggi, one can picture Trump extending his hands, palms up, in the words, “Our intelligence agencies continue to assess all information, but it could very well be that the Crown Prince had knowledge of this tragic event — maybe he did and maybe he didn’t!”

Conclusion

Multilateralism is nice, but when national interests are at stake, it’s the money and the power that matters. Obviously. We have seen this money-power dynamic play out in the Khashoggi and Huawei incidents. Canada and the US are loathe to criticize their allies when the chips are down, especially when there is big money at stake. Regarding Huawei, Canada is being played by the US, caught in the middle of a trade spat it has no say in. Back against the wall, though, it will be the United States that Canada turns to, not China. If no diplomatic solution is found to free Meng and the three imprisoned Canadians, Canada will reluctantly turn her over to American authorities. We may not like it, but we know what we have to do to save our Cdn. bacon.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd is on Twitter

Ahead of the Herd is now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd is now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified.

Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.