The Arctic: The next ‘Great Game’ – Richard Mills

2025.02.22

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia and Tibet. The two colonial empires used military interventions and diplomatic negotiations to acquire and redefine territories in Central and South Asia. Russia conquered Turkestan, and Britain expanded and set the borders of British India. By the early 20th century, a line of independent states, tribes, and monarchies from the shore of the Caspian Sea to the Eastern Himalayas were made into protectorates and territories of the two empires. — Wikipedia

Today, a new Great Game is in its early innings, to use a baseball analogy. The players are Russia, China and the United States, and the playing field is the Arctic.

As an Arctic nation, Canada has a role to play, but it’s a role that is being diminished by the United States, which sees Canada as less a partner than a nation vulnerable to attack that needs protecting.

Is this the reason President Donald Trump has been musing about making Canada the 51st state? Steve Bannon thinks so. The former top Trump aide in an interview with Global News said that Canadians are “misreading the situation” by focusing on tariffs, and that Trump’s real interest in Canada is strategic and geopolitical:

“The world is now coming to Canada, and it’s coming in a big way,” Bannon says with a prophet’s conviction.

“You were isolated before. You’re not isolated now.”

That’s because, Bannon says, the Arctic is going to be the “Great Game of the 21st century” and a military weakness that he calls Canada’s “soft underbelly.”

Global warming

Once considered too remote, too cold, and too inhospitable for civilization, the Arctic has been transformed by global warming.

Over the past 35 years, the Arctic has warmed more than any other region on earth – by 3.1 degrees in the coldest six months of the year, October to May.

When sea ice is lost, the sunlight is no longer reflected back to the atmosphere, but rather gets absorbed into the open ocean. This exacerbates ocean warming and forms a warming cycle. Warmer water temperatures delay the growth of ice in fall and winter, and the ice melts faster in the spring, exposing patches of open ocean for longer periods during summer, and further warming the ocean.

According to NASA, Arctic sea ice measured in September – when it is thinnest — is now declining at a rate of 13.2% per decade.

Along with calving glaciers, shrinking ice caps and disappearing sea ice, evidence of Arctic warming can also be seen in the thawing of permafrost.

It had been assumed that the melting of the top layer of tundra that remains frozen year-round would be a slow process, releasing carbon as the ground thawed. In fact, the permafrost melt is happening much quicker than expected. Scientists studying the phenomenon are finding “Instead of a few centimetres of thaw a year, several metres of soil can destabilize within days. Landscapes collapse into sinkholes. Hillsides slide away to expose deep permafrost that would otherwise have remained insulated,” states CBC.

In some places the thaw is happening so fast, the earth is swallowing up equipment left there to study it, Global News reports. The fast-melting areas are known to contain the most carbon, meaning that permafrost is probably going to release 50% more greenhouse gases than expected, including methane which is far more efficient than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

One-fifth of Arctic permafrost is now vulnerable to global warming, according to a University of Guelph biologist, whose research was published in ‘Nature’.

Environmentalists, First Nations and other residents in the sparsely populated Arctic decry the effects of global warming, but where some see loss of animal habitat, like polar bears, in the melting ice, and a disappearing way of life for Inuit hunters, others see opportunity.

Territory grab

A “territory grab” is happening in the Arctic, as polar nations jostle to control their share of a vast expanse of ocean and land that is rich in natural resources, and as the ice retreats, is beginning to open new trans-polar shipping routes that hold great promise for seaborne trade.

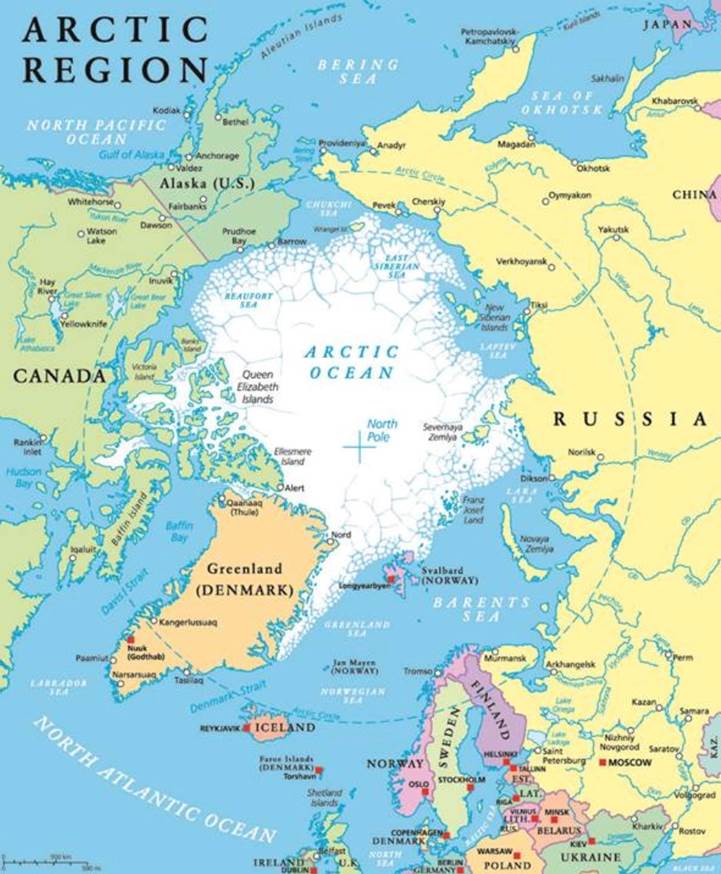

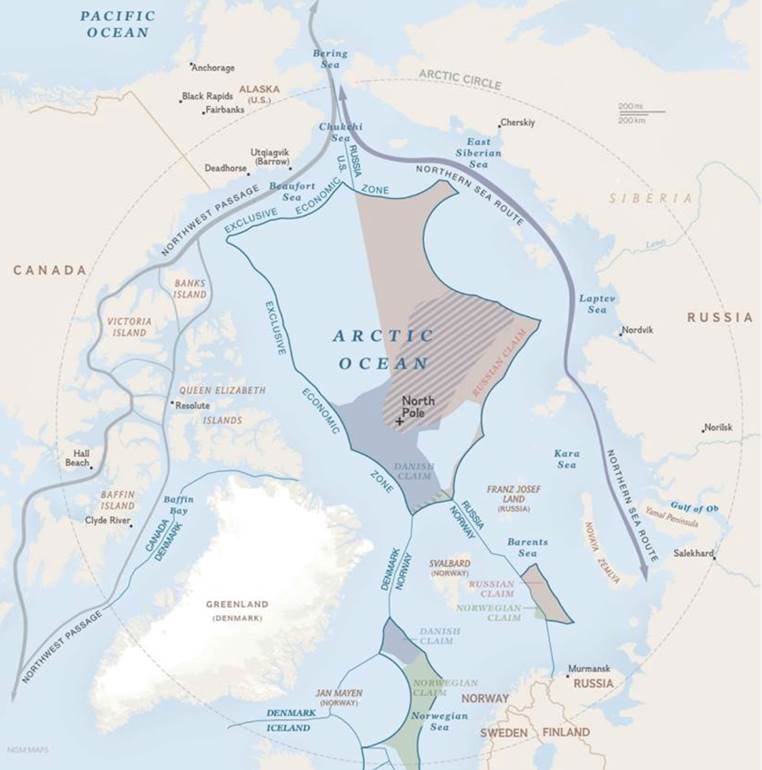

Who has jurisdiction over the North Pole, the Arctic Ocean, inland seas and land masses that we refer to as the Arctic? Control over all of this 20-million-square kilometer territory including “exclusive economic zones” (EEZs), is divided among the eight Arctic states: Canada, the United States, Russia, Norway, Denmark/Greenland, Iceland, Sweden and Finland.

EEZs are zones prescribed by the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Within these zones, a state has the right to explore and extract marine resources including hydrocarbons underneath the seabed, and energy produced from water and wind. EEZs stretch out 200 nautical miles from the coast. An Arctic nation, within the EEZ, has rights below the the ocean surface, but nobody owns the surface – they are known as international waters. The North Pole and the surrounding Arctic Ocean, for example, are not owned by any one country.

This sort-of shared ownership has caused some disputes over what is considered to be an international seaway and who has the right of passage. Six of the eight Arctic nations regard parts of the Arctic seas as their own. A country that ratifies the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea has 10 years to make claims on a continental shelf that gives it rights to resources on or below the shelf’s seabed; Norway, Russia, Canada and Denmark all have claims on continental shelves below their EEZs. The US has signed the convention but hasn’t ratified it.

When the Arctic Ocean was covered with a thick sheet of ice, this arrangement worked reasonably well, with little conflict. But the disappearance of the ice has stirred the imaginations of polar nations intent on taking advantage of more accessible natural resources and shipping routes.

If current climate trends continue, scientists estimate that the Arctic Ocean will be ice-free by mid-century. To clarify, that means sometime between 2030 and 2050, in September, the month with the least amount of ice cover, the Arctic Ocean will be entirely uncovered by ice.

Russia was the first to claim Arctic ownership beyond its territory, in 2007. Russia has also reportedly been expanding infrastructure along its northern coast to exploit natural gas reserves.

Canada claims ownership of the Arctic Ocean archipelago. To asserts its claims, the country has created a new research center, is developing autonomous submarines, and conducting search and rescue exercises in anticipation of growing ship traffic in the Northwest Passage.

But countries’ investment in the Arctic is rather un-even. Despite having the second largest amount of land mass within the Arctic Circle, behind Russia, Canada has spent very little, as has the United States with only the northern third of Alaska considered to be Arctic.

The big spenders are Russia and Norway. National Geographic notes that Russia has “greatly expanded its military forces in the Arctic, becoming, by most measures, the dominant cold-weather player.” Russia’s northern fleet is the largest in the world at 60 ice breakers and another 10 under construction. Norway has expanded its ice-capable fleet to 11 ships. Both countries have invested heavily in oil and gas development.

To be fair, Canada and the US operate bases in the Northwest Territories and Alaska capable of dispatching troops, aircraft and submarines. NATO countries regularly train for cold-weather conflict.

However, compared to Russia, and for that matter, China, not even a polar nation, Canada’s Arctic efforts pale. The government has no official Arctic policy and there is an extensive list of unfulfilled infrastructure promises including no high-speed Internet. The only significant project has been a paved road completed to the Arctic coast at Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories.

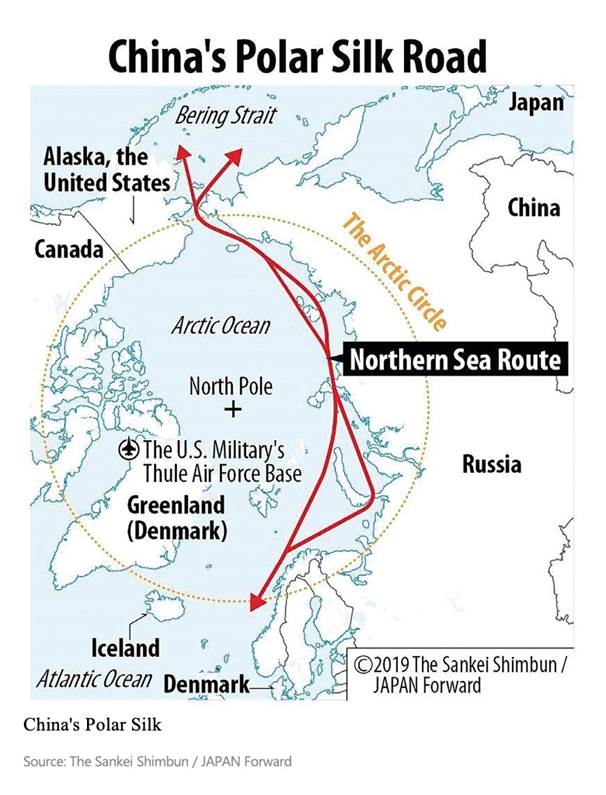

Lately China has become more interested in the Arctic, eyeing less ice cover as an opportunity to expand its ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI). The ‘Polar Silk Road’ would be an extension of its ambitious plans for a series of BRI infrastructure spends designed to create a trading orbit in southern Asia. The Polar Silk Road includes a potential shipping route across the Pacific and the development of energy and mining resources in the region, plus fishing and tourism.

The country is hoping to diversify its energy resources away from the Persian Gulf and Africa, by investing in Russia’s Yamal LNG complex and in Norway’s oil and gas fields.

In 2013 China was granted observer status on the Arctic Council, an inter-governmental discussion forum.

The combined Arctic moves of Russia and China have raised alarm bells in Washington, which fears its old Cold War enemies are planning to exercise territorial ambitions in the far north.

During Trump’s first term, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned his fellow foreign ministers at a meeting of the Arctic Council –– that the Arctic is emerging as a new “Great Game” between the US, Russia and China (notice Canada is not included), or maybe even a renewed Cold War.

Pompeo called out Russia’s claim over international waters of the Northern Sea Route and its moves to re-open military bases along the route as commercial shipping activity increases. And he disparaged China for even claiming to have a say in Arctic policy, noting that “the shortest distance between China and the Arctic is 900 miles.”

“Beijing claims to be a near-Arctic state,” Pompeo said, referring to China’s 2018 white paper on the Arctic. “There are Arctic states and non-Arctic states. No third category exists. China claiming otherwise entitles them to exactly nothing.”

For critics who thought that Pompeo shouldn’t be using the Arctic Council to make pronouncements of a political or military nature, he had this to say:

“We’re entering a new age of strategic engagement in the Arctic, complete with new threats to Arctic interests and its real estate.”

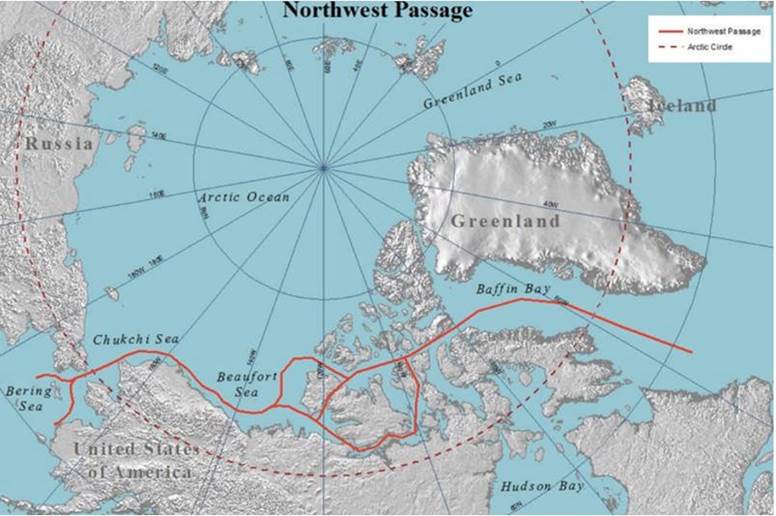

And in keeping with the Trump administration’s pugilistic approach to Canada, Pompeo disputed Canada’s claim to the Northwest Passage as internal waters, arguing the waters should be considered international.

As Russia, China, and increasingly, the US flex their Arctic muscles, Canada is the 90-pound weakling in the gym – having instituted a five-year ban on offshore energy exploration.

Ice-free shipping

The opening of polar sea routes as a consequence of melting ice is a double-edged sword. On the one hand it presents a huge opportunity for polar nations to increase trade and to drastically cut transportation expenses. Yet increased commercial activity also heightens the possibility of conflict especially in an area where ownership to surface and undersea rights isn’t always clear.

Pompeo told his Arctic Council peers that new, ice-free sea lanes could become “21s century Suez and Panama Canals,” which would “potentially slash the time it takes to travel between Asia and the West by as much as 20 days.”

Indeed, a ship sailing from East Asia to Western Europe through the Northwest Passage, instead of having to go through the Panama Canal, could potentially cut 10,000 kilometers from the voyage. Imagine how much fuel that would save shipping companies, and crewing costs, plus the opportunity to deploy more vessels more frequently.

Melting sea ice is already opening up the Arctic Ocean. Climate scientists at UCLA in California, studying the impact of rising temperatures on shipping, found that by mid-century, ships will be able to travel the Northern Sea Route for three months during the summer without icebreakers.

In 2018 a Danish freighter owned by Maersk became the first container ship to sail through the Northern Sea Route.

Resource treasure chest

At Ahead of the Herd we always follow the money to discover the reasons behind most decisions. It’s no exception with the Arctic, which contains a veritable treasure trove of natural resources – mostly oil and gas but some minerals too.

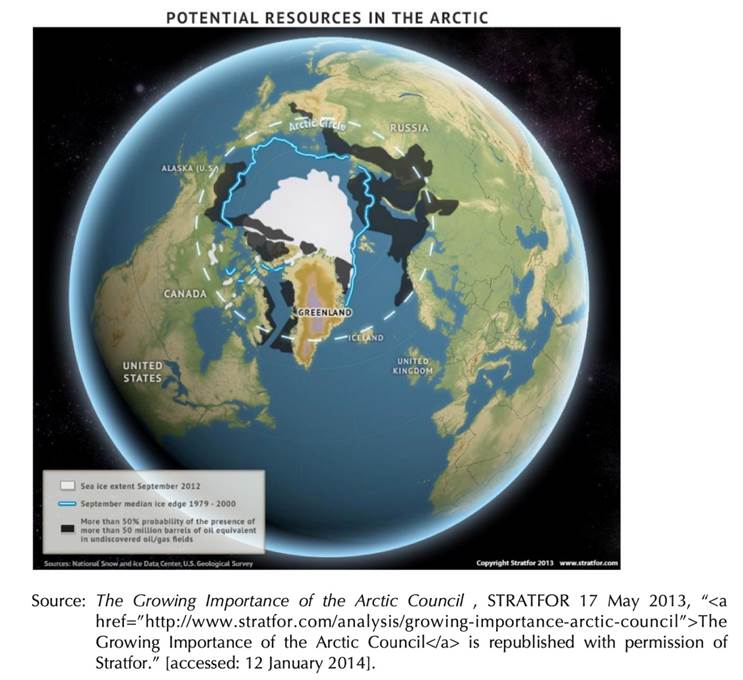

According to the US Geological Survey, the Arctic Circle (areas beyond the 200-nautical-mile economic exclusion zones are international ) contains up to 30% of the world’s undiscovered gas and 13% of its oil.

The Beaufort Sea off the coast of the Northwest Territories holds an estimated 56 trillion feet of natural gas and 8 billion barrels of oil.

Among the non-energy minerals hidden within the Arctic’s barren lands are coal, diamonds, uranium, phosphate, nickel and platinum group elements (PGE). Rare earth elements and cobalt needed for electric vehicles have also been found in the Arctic regions of Russia and Scandinavia.

The Arctic is estimated to hold nearly 22% of the world’s undiscovered oil and natural gas reserves, with Russia accounting for 52% of the Arctic’s total energy resources and Norway holding 12%.

However, it’s possible that, despite Russia being a major producer of cobalt, chrome, copper, gold, lead, manganese, nickel, platinum, tungsten, vanadium, and zinc, a shortage of critical raw materials is one reason for its interest in the Arctic.

According to Defense Blog, hackers obtained access to classified presentations outlining Russia’s mineral resource development strategy through 2035.

The documents expose Russia’s growing dependence on imported raw materials and its declining domestic resource base:

The documents indicate that Russia is struggling to compensate for the depletion of its mineral reserves. Over the past 25 years, the discovery of new deposits has declined tenfold, and the extraction of strategic minerals has outpaced their replenishment…

One of the most alarming revelations is Russia’s near-total dependence on imports for key industrial metals. The country lacks sufficient domestic reserves of manganese, chromium, lithium, cobalt, and copper—essential components for modern technology, defense, and infrastructure. Some of these, such as lithium, have become even more inaccessible following the loss of Ukraine’s mineral deposits. Russia’s supply of cobalt, crucial for military electronics, relies almost entirely on foreign sources, making it vulnerable to economic sanctions and geopolitical disruptions.

Government investment in geological exploration has also seen drastic cuts, with funding reduced by 94 billion rubles. Private sector investment has not been able to fill the gap, further weakening efforts to secure new mineral deposits. As a result, Russia remains largely dependent on exporting unprocessed raw materials. Oil, gas, coal, and iron ore account for more than half of the country’s total exports, underscoring its failure to diversify its resource economy.

The leak also sheds light on Russia’s intensified efforts to secure raw materials from foreign suppliers. In response to shortages, Moscow has ramped up critical mineral imports from China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Mongolia.

The Arctic Great Game

The Arctic is now identified as important in a potential superpower conflict. According to Deccan Herald, with summer sea ice shrinking by 12.2% a decade, this region is not only strategic from an economic, rare-earth minerals, and maritime-trade route perspective, but also a war-fighting perspective.

The article makes several important points:

- The US Department of Defence Arctic Strategy (2024) calls for a new strategic approach as the region is becoming a venue for strategic competition amid a new geopolitical climate. In addition to the Ukraine crisis, the accession of Sweden and Finland to NATO and accelerating impacts of climate change, the increasing collaboration between China and Russia in the Arctic is inducing strategic instability. The Arctic has now moved into the focus of the US, Russian, and Chinese strategic considerations – the three great powers within the international system.

- Militarization of the Arctic is closely linked with Russia’s Special Military Operations in Ukraine which began with Russia securing its southern flank at Crimea in the Black Sea in 2014. With Sweden and Finland joining the Atlantic alliance following the Ukraine War, the non-Russian Arctic is now a NATO territory — an undesired outcome for Russia — with seven out of the eight Arctic nations now NATO members.

- After Russia’s invasion of Crimea and its annexation by the use of force in 2014, Russia approved and released its maritime doctrine in 2015 and replaced it with a new maritime doctrine in July 2022 amidst its Special Military Operations against Ukraine since February 2022. The objective of Russia’s ongoing military campaign is to reconfigure Ukraine’s territory into a “land-locked” countrywith no access to the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. Free access for the Russian fleet to the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans is one of the cornerstones of Russia’s strategic priorities in the Arctic.

- From China’s geo-political and military perspective, controlling the Arctic allows one to obtain the “three continents and two oceans’ geographical advantage” over the Northern Hemisphere.

- With China christening itself as a near-Arctic state, the US seeks to exercise its forces to build readiness for operations at high latitudes. Along with the seabed, outer-cyber space and the Antarctic, the Arctic region constitutes the ungoverned “new strategic frontiers” ripe for a great power rivalry.

RT explains that, while Russia has long maintained a dominant Arctic presence, NATO’s expansion northward has compelled Moscow to significantly increase its military footprint. The column, by Air Marshal Ani Chopra (Retired), a veteran Indian Air Force fighter jet pilot and the former director-general of the Center of Air Power Studies in New Delhi, states:

Both Russia and the United States have long maintained military bases and surveillance systems in the Arctic, including nuclear deterrent capabilities.

Russia has operated nuclear-powered icebreakers in the region for some time. Although the Arctic Military Environmental Cooperation (AMEC) agreement between Russia, the US, and Norway facilitated the decommissioning of certain Soviet and US assets, the increasing interest from additional nations has sparked a new Cold War dynamics between the two primary powers.

The cooperative atmosphere that once prevailed has deteriorated, particularly in light of geopolitical tensions stemming from the situation in Ukraine since 2014.

One of the most important aspects of the Artic Great Game in the Northern Sea Route, or NSR. The route runs along the Arctic coast of Russia. Ice generally clears up here first, putting it an advantage compared to the other routes such as the Northwest Passage and the Transpolar Sea Route. The NSR cuts the distance between East Asia and Europe from 21,000 kilometers via the Suez Canal to 12,800 km, saving shipping times from between 10 and 15 days.

The Northwest Passage could also reduce shipping time between the Middle East and Western Europe to around 13,600 km compared to 24,000 km via the Panama Canal, but parts of the route are just 15 meters deep, reducing its viability, notes Air Marshal Chopra.

Chopra maintains that Russia is the largest stakeholder in the Artic, which contributes about 10% of its GDP and accounts for 20% of Russia’s exports.

Russia’s New Arctic Policy 2035, signed in 2020, asserts its sovereignty over the NSR. Moscow has threatened to use force against vessels that do not comply with Russian regulations in the NSR, setting up a potential standoff between Russia and the US, which advocates for NSR to remain an international waterway.

Of course, the new player in the Arctic is China, which despite not having any territory bordering the Arctic Circle, has inveigled itself into becoming a “near-Arctic state”.

China’s official Arctic Policy paper, released in 2018, highlights its interests in Arctic resources and the need to develop infrastructure for research, military, and other purposes. China views the Arctic as a vital source for energy and minerals.

As written by Air Marshal Chopra,

China invests more than the United States in Arctic research and operates a Polar Research Institute in Shanghai. It possesses a fleet of research vessels and two MV Xue Long icebreakers. Additionally, China established the Arctic Yellow River Station in 2004. In 2018, COSCO Shipping Corporation Limited, based in Shanghai, made eight transits through the Arctic between Europe and China.

China’s “Polar Silk Road,” launched in 2018 as a joint initiative with Russia, aims to enhance connectivity in the region. Like Russia, China also aspires to deploy nuclear-powered icebreakers in the Arctic, becoming only the second country to do so. However, Denmark, encouraged by the United States, rejected China’s offer to purchase an old military base in Greenland and build an international airport there.

Regarding the Arctic Great Game, Chopra notes that, unlike Antarctica,

Arctic states possess established territorial claims under the Law of the Sea regime.

Russia’s Northern Fleet is strategically positioned across the Arctic and holds a dominant stance in the region…

Notably, the Northern Sea Route (NSR) offers a transportation route that is 37% shorter for cargo traveling from London to Yokohama, Japan, compared to the Suez Canal. Russia seeks to leverage this advantage economically through a robust support infrastructure along its Arctic coastline. Moscow perceives the US and its NATO partners as threats to its Arctic ambitions.

As the great Arctic race progresses, Russia’s resource-driven economy leads in exploitation efforts, having secured rights to approximately 1.7 million square kilometers of seabed. Moreover, Russia has revived several Soviet-era military bases and modernized its naval capabilities, now operating seven nuclear-powered icebreakers alongside around 30 diesel-powered vessels. In contrast, the US and China each operate only two diesel-powered icebreakers. NATO has also intensified military exercises in the Barents Sea and Scandinavian regions.

Tom Rhodes, chief operating officer at Montrose Associates and a former Washington correspondent for the New York Times, writes that, The past decade of Russian aggression has spawned many water-borne consequences, not least those affecting maritime routes around the Black Sea and the questionable hybrid assault on the Nord Stream pipelines in the Baltic. But Putin has always viewed the Arctic as the ultimate prize.

According to Rhodes, Putin wants to further develop the Northern Sea Route, already mentioned. But, he notes that Western sanctions have to an extent curbed Putin’s dream of a “gas El Dorado” in the Gulf of Ura where Novatek, Russia’s biggest private gas company, has been building two LNG export facilities.

For China, whose continued purchase of Russian oil and fuel exports has kept the Russian economy afloat throughout the Ukraine conflict, the NSR provides serious opportunity. It offers potential access, not merely to the Arctic’s oil and gas deposits but also other untapped assets including uranium, rare earth minerals, gold and diamonds. Both countries will be able to develop the NSR on Russia’s coasts and provide further ice-breaking ships.

In July 2024, it was reported that Sibir, a Russian nuclear-powered icebreaker was escorting the light ice- class vessel Xin Xin Hai 1 on its voyage from the Port of Taicang near Shanghai via the Bering Strait and the NSR to the Port of Arkhangelsk before travelling on toward ports in northern Europe. The New Shipping Line of Hainan Yangpu, which owns several ice-class vessels, completed seven transits between July 2023 and December 2023, and in June 2024 signed an agreement with Rosatom, the all-powerful Russian state corporation to establish a year-round arctic shipping route.

For the United States, Foreign Policy magazine cleverly assets that, the point about the looming Arctic challenge isn’t to build more Western icebreakers—which mostly carry scientists and science projects—but to make sure that the main Arctic rival of the United States and its NATO allies can’t really take advantage of any ice that it breaks.

The piece explains that, while the Russian Arctic does have “mind-boggling amounts” of oil and natural gas, and that Russia has managed to tap these reserves despite a decade of Western sanctions, the hard part is moving that gas from the Russian north to Asian markets.

Especially after the onset of the war in Ukraine, which largely foreclosed European energy export markets to Russia, Arctic energy and its shipping routes to the east have become a key strategic priority for Putin. The Yamal Peninsula in northwest Siberia is the epicenter of Russia’s newfound trade in liquefied natural gas, or LNG; since piping it to Europe is no longer an option, and China is proving a hard bargainer on piped gas headed east, freezing it and shipping it out is the future for Russian energy.

This is why Russia’s Northern Sea Route is so important. It allows Russia to do an end-run around Europe and ship gas directly to China. In 2023 the NSR had its best year ever, shipping 36 million tonnes of cargo.

Still, this doesn’t mean that Russia is free of the West’s punitive measures. As explained by Foreign Policy,

About half the traffic on the NSR is LNG exports. Shipping gas through ice floes requires icebreaking LNG tankers. Those were previously being built for Russia in South Korea, but the Ukraine war put paid to that, with Seoul canceling the pending delivery of new ice-class tankers…

Just after the invasion of Ukraine, Western sanctions poleaxed the big LNG liquefaction facility in the Yamal Peninsula, which was reliant on Western technology. Novatek, the private Russian company plowing ahead, now hopes to jury-rig a solution to get its gas super-chilled and super-moving by 2026, but it is employing unproven workarounds…

The West has found other chinks in the armor. This summer, the European Union, in its 14th sanctions package on Russia, specifically targeted Russian transshipment of LNG in European ports…

Or take the latest Western step to hit Russia. In late August, the United States went after Russia’s LNG shadow fleet with new sanctions.

The latest sanctions not only intensify the pressure on Russian gas production and liquefaction in the Arctic, but they also take aim at the fleet of specialized tankers that Moscow needs to build up in order to get its product to its last remaining big market. The goal, the U.S. State Department said, is to “further disrupt” both production and export of Arctic LNG, especially relevant now that the big plant in Yamal is up and running again…

“We are pressuring Russia with economic tools in the Arctic, which is a cost-effective means of pursuing our goals. Russia’s icebreaker fleet is all about energy exports to Asia,” Rebecca Pincus, director of the Polar Institute at the Wilson Center, said. “That’s why the sanctions are smart. If we can sustain them, and the Russian Arctic oil and gas reserves and facilities become stranded assets, then what is the Arctic to Russia? That could end up starving the NSR.”

Russia-US rapprochement

The next twist in the Arctic Great Game may surprise readers, or not, depending on how well you’ve been following US politics.

In the news right now is the meeting between Trump officials and Russian diplomats discussing a potential peace deal. The meeting in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia excluded Ukraine.

Before the talks, Trump reportedly called Putin and promptly conceded to most of Moscow’s Ukraine demands, which include Ukraine not joining NATO, not getting its Russia-occupied territory back, and a call for wartime elections to get rid of Zelensky.

Trump enraged countries and individuals supporting Ukraine when he suggested that Ukraine started the war and that Zelensky should have agreed to negotiations sooner.

He also baselessly claimed that half of the aid okayed by Congress to help Ukraine has gone missing. CNN reports that,

In reality, more than half the US aid to Ukraine has been in the form of weapons systems and ammunition from US stockpiles. The money went from US taxpayers to US-based defense contractors to buy the weapons and equipment for America’s military inventory, and some of that stockpile was then sent to Ukraine.

There is some truth to the idea that America is losing money in Ukraine and that cozying up to Russia would be lucrative for both countries.

According to Oilprice.com, The Kremlin is signaling that it’s once again open for business with American oil companies—if the political winds shift. Russian Direct Investment Fund chief Kirill Dmitriev told reporters ahead of talks in Saudi Arabia that Moscow sees a return of U.S. firms as inevitable, arguing that American majors once thrived in Russia and they would be unwise to ignore the opportunity again.

Russia, says Oilprice, is facing mounting pressures to fill the void left by Western oilfield giants like Halliburton and Baker Hughes which exited the country after sanctions took hold.

The country remains dependent on Western equipment such as that used in hydraulic fracturing/ fracking. For now, ExxonMobil is the only major US oil firm tied to Russian assets — the company was forced to abandon its stake in the Sakhalin-1 project after sanctions hit but Moscow has twice extended the deadline for the sale, now pushing it to 2026, author Julianne Geiger writes for Oilprice.

Speculation is rife that US-Russia talks could lead to a softening of sanctions.

Reuters reports that, should the Trump administration move to ease restrictions on Russia, it could open the door for companies to return.

The article states that Western companies have lost $107 billion by leaving Russia. Included in the exodus of more than a thousand firms were McDonald’s, Danone and Carlsberg. US companies alone lost

$324 billion by leaving Russia.

As for which companies could return, those involved in supplying good for both civilian and military applications are bound by Western restrictions. This includes Boeing and Airbus.

Kirill Dmitriev, the head of Russia’s sovereign wealth fund, told Reuters he expects a number of US companies to return to Russia as early as the second quarter, adding that he believes US oil majors that had been successful in Russia would “at some point” return.

An article penned by Bloomberg claims ‘Ukraine is Just a Pawn in a Russian Reset’. It cites Secretary of State Marco Rubio saying that lifting economic sanctions is a concession the United States won’t make until there’s a final deal. Still, the importance of the US-Russian economic relationship was laid threadbare when Rubio stressed the “incredible opportunities that exist to partner with the Russians, geopolitically on issues of common interest, and frankly economically” that ending the war would create.

Interestingly, the piece frames Trump’s view of Putin in ideological terms, stating,

Russia is by no means the enemy in Trump’s eyes, or those of like-minded ultra-nationalist political parties across the democratic West. Putin’s Russia is to them more a brother in arms in the fight against liberalism — domestic or international — that unites them all. Ukraine, meanwhile, has been championed as a fight for the liberal world order.

Canada’s interests

What does the Arctic Great Game mean for Canada, an Arctic nation of which around 40% of its territory touches the Arctic Circle?

Unfortunately, not much. If Russia or China were to invade Canada from the north, an increasingly likely scenario given the natural resources that lie beneath the disappearing polar ice cover, it would have little chance of defending itself.

Canada does not have a military base in the Arctic, though it has a number of installations and stations in the north. (Google AI Overview)

The country has long recognized the problem, with leaders calling for beefed-up security in the Arctic. Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has called for a joint Canada-US NORAD base in northern Canada.

The federal government late last year announced it was committing CAD$34.7 million up front and $7 million over five years for a new Arctic policy — an amount that pales in comparison to Denmark’s recent pledge of USD$2 billion and a 2017 promise from the US for $5.2B.

Canada will also appoint a new Arctic ambassador and set up two new diplomatic missions in Alaska and Greenland.

Global News notes the policy includes no new defense spending in the Arctic, despite a threat assessment by the Conference of Defense Institute that listed climate change, threats from China, Russia and others, and “an eroding international order based on the rule of law” as the top threats facing Canada in the Arctic.

It adds The federal government has been pushed by the United States to step up its posture and investments in the North as part of its defence commitments to both NATO and NORAD.

The updated defence policy includes billions of dollars in new Arctic security investments, on top of nearly $40 billion in previously-announced spending for NORAD modernization.

Ottawa’s pledge to meet NATO’s defence spending target of two per cent of GDP by 2032 — a timeline that’s been criticized by allies as too long and the parliamentary budget officer as unrealistic — is based in part on purchasing a new fleet of submarines to patrol the North.

Canada signed a trilateral pact with the U.S. and Finland in July to spur the production of new Arctic and polar icebreakers, and signed a memorandum of understanding last month to enhance the partnership.

But wait. Could the Canadian government actually be getting serious about Arctic defense? This just in: On Feb. 20,

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the Minister of National Defence, Bill Blair, Canada’s Ambassador to the United States, Kirsten Hillman, and Canada’s Fentanyl Czar, Kevin Brosseau, met virtually with Canada’s premiers to discuss Canada-U.S. relations and Arctic security.

Our North, Strong and Free, the $73 billion defence policy update the federal government launched in 2024 includes major investments in the North, such as airborne early warning and control aircraft, specialized maritime sensors, new tactical helicopters, a new satellite ground station in the Arctic, and northern operational support hubs, in addition to a separate $38.6 billion investment in NORAD modernization.

Conclusion

In the article cited at the top, Steve Bannon asks why, given that Canada is more likely to be invaded by Russia than the United States, the country spends a smaller amount on the region than the US (though not anymore, if the spending announcement Wednesday comes to fruition).

Bannon argues that if Canada doesn’t do more to protect its northern frontier, and in turn, protect the US, Trump will force us to:

By annexing Greenland, retaking the Panama Canal and securing Canada’s northern border, Trump is apparently trying to establish a north-south economic and military corridor.

It’s all about “hemispheric control,” Bannon says.

“Let me be brutally frank. Geo-strategically, you don’t really have an option [but to join us] if you want your sovereignty because from the north, from the Arctic, it’s going to get encroached in a great power competition that you don’t have the ability to win.”

“This is a major geostrategic job … Look at your northern border. You’re totally, completely exposed … it used to be your greatest defence. Now it’s your biggest vulnerability,” Bannon says.

While Trump’s pronouncements about annexing Greenland, making Canada the 51st state, slapping 25% tariffs on its second largest trading partner, and retaking the Panama Canal, may seem like the rantings of a madman, they make more sense in the context of hemispheric control.

Bannon isn’t sure whether those tariffs are a tool of economic force being exerted over Canada to bend to Trump’s Arctic empire-building exercise or if it’s a way for Canada to buy into the protection the U.S. will offer from encroachments.

He’s more certain about Greenland.

Annexing Greenland means a U.S. submarine base can be built to block the Russian navy from its bases in Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. Then, the Northwest Passage — a network of waterways that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago — “changes the economics of trade with Asia, with Japan and East Asia and with that part of Russia,” Bannon says…

“Before, strategically, you didn’t need the United States. They were nice to be an ally of — now you need us. It’s the only way to stop the great power competition, which you’re going to lose. Tell me how that’s going to play when Russia and China start making physical incursions into northern Canada … how are you guys going to respond? Are you going to lose northern Canada?

“Well, if you’re partners and/or part of the United States, you don’t have to worry about that because we’re not going to let that happen.”

Of course, Canada will never let itself be absorbed by the United States no matter how real the threat is from “the other side of the ice.” At the moment it’s unclear whether the threat is more from Russia or China.

The Trump administration and just about everyone in Congress now views China as the enemy, so there is an argument to be made that the Canadian Arctic should be fortified to resist an invasion from the PLA.

What could the United States cozying up to Russia mean for Canadian Arctic sovereignty? Canada has 40% of its land mass touching the Arctic Circle while the US only has Alaska, so it’s unlikely that Russia would invade the continental US via Alaska. The US has two military bases the state — Fort Wainwright and Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson.

Canada’s northern frontier, on the other hand, remains undefended.

If Canada’s Arctic sovereignty was threatened, would the United States come to our defense? Trump’s argument seems to be “only if you join us.”

Meanwhile, the focus seems to be on getting a deal with Russia to end the war with Ukraine. For Trump ending the war is good business. If Trump and Putin can get Zelensky to agree to concessions — and there will be concessions — it is likely that sanctions will be loosened and US companies will return to Russia.

American oil companies lost over $300 billion when Russia invaded Ukraine. They want back into Russia and Trump appears to be setting the table for such an outcome.

This could lead to further arrangements with Moscow to carve up the Arctic. Consider: If the US has Alaska, puts submarine bases on Greenland, demands access to the Northwest Passage despite Canada’s protestations, and has American oil companies (and others) operating in Russia with Putin’s blessing, don’t they basically own the Arctic?

All without firing a shot. US-Russian cooperation in the Arctic could be a unique twist in the next Great Game.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Share Your Insights and Join the Conversation!

When participating in the comments section, please be considerate and respectful to others. Share your insights and opinions thoughtfully, avoiding personal attacks or offensive language. Strive to provide accurate and reliable information by double-checking facts before posting. Constructive discussions help everyone learn and make better decisions. Thank you for contributing positively to our community!

#thegreatgame