BC earthquakes and fracking

2018.12.16

There is no fracking going on right now in northeastern British Columbia, the epicenter of the province’s oil and gas production. Hydraulic fracturing operations have been shut down there for a month due to earthquakes that happened on Nov. 29 about 20 kilometers southeast of Fort St. John.

The BC Oil and Gas Commission (BCOGC), which both regulates and promotes the industry (more on that below), is investigating the 4.5 magnitude quake, followed by two smaller aftershocks. One of the largest oil and gas producers in Canada, Canadian Natural Resources, was fracking in the area.

The commission has linked previous earthquake incidents to increased seismicity, though it states on its website that none of the events in BC have resulted in environmental or property damage. Yet.

For those who have been following our investigations into the BC government’s plans to develop a liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry in BC – something we vehemently disagree with considering its costs will vastly outweigh its benefits – there is an irony in the operations suspension.

A couple of months ago the BC Premier and the Prime Minister gathered with industry representatives to announce the final investment decision by Shell and its Asian partners to go ahead with LNG Canada. The first-in-BC $40 billion LNG compression plant, to be built in Kitimat, will receive natural gas via a new pipeline – filled with the same fracked gas that is causing earthquakes and shutting down the industry while the BCOGC investigates. It would be downright shocking if they found anything that would slow fracking in northeastern BC, which supplies natural gas to BC and Alberta, as well as valuable liquefied gas products like diluted bitumen (dilbit) to the oilsands, not to mention hundreds of millions in royalty payments to the BC and Alberta governments.

This article will take a deep dive into the environmental effects of fracking, specifically earthquakes in British Columbia, a seismically active region where hundreds of small and some large dams would be damaged should the Earth shake too close to them. If what you read doesn’t shock you, it should.

Fracking and earthquakes in BC

In hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, a concoction of chemicals, water and frac sand is pumped into a well at high pressure to break apart the shale rock in order to create fissures that release the natural gas. The fracking fluid and natural gas is then pumped back up and “burped” for several weeks, while the gas is separated from the fluids. Sour gas is burned, releasing carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide into the environment. Thirty to 40% of the fracking fluid is left in the well. The “flowback liquid” that is left after the gas is extracted contains water and a number of contaminants, including radioactive material (like radium, which can cause leukemia), heavy metals, hydrocarbons, bromide and other toxins.

This wastewater is then stored in pits, injected deep underground, or treated off-site.

The wastewater pumped underground goes into oil and gas waste wells or saline aquifers. There are serious concerns about the ability of these waste wells and aquifers to handle the increased pressure. The evidence is showing that deep-well injecting, and fracking, are linked to the occurrence of earthquakes.

The link between fracking/ wastewater injection and earthquakes has been strenuously denied by the industry. But a study published in 2016 found that both fracking wells and wastewater disposal wells, increase seismicity. Researchers “compared the relationship of 12,289 fracking wells and 1,236 wastewater disposal wells to magnitude 3 or larger earthquakes in an area of 454,000 square kilometers near the border between Alberta and British Columbia, between 1985 and 2015,” explained a press release. They “found 39 hydraulic fracturing wells (0.3% of the total of fracking wells studied), and 17 wastewater disposal wells (1% of the disposal wells studied) that could be linked to earthquakes of magnitude 3 or larger.”

A major research project testing seismicity in northeastern BC found a 13-fold increase in the number of earthquakes under 2.5, from just 14 between 2009 and 2013, to 186 for one year, between August 2013 and August 2014.

The data corresponds with a dramatic increase in natural gas production in both BC and Alberta during roughly the same time period.

In 2015 the BC Oil and Gas Commission confirmed that fracking caused a 4.6-magnitude earthquake three kilometers from a project operated by Progress Energy. This earthquake was the largest in the world caused by a fracking operation.

The quake on Nov. 29 was almost as large, 4.5 on the Richter Scale. A preliminary investigation found it was “very likely” caused by fracking.

So how exactly does fracking cause earthquakes and more importantly, could these earthquakes be destabilizing the ground and making it more likely that larger, more dangerous earthquakes will occur?

According to Honn Kao, a research scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, there has to be at least two factors: a large volume of fracking fluid injected into the well; and an area where tectonic plates are under pressure. A larger volume of fracking fluid could in theory trigger a bigger quake.

In a radio interview with CBC Daybreak, Kao said:

“We know that induced earthquakes are generally very shallow and they can sometimes cause stronger ground shaking at places near the epicentre, even though their magnitudes are relatively small.

Also, because the number of smaller magnitude events increases, that implies that the chance of having relatively larger events increases, as well.

So for these two reasons, the seismic risk associated with the development of shale gas and oil should not be overlooked, and they should be closely monitored as the development of unconventional hydrocarbon resources continues”

Questionable regulator

“Shale oil and gas should be closely monitored.” Let’s turn this statement around to read: Is BC shale oil and gas being closely monitored? Having done a little digging, the answer is no. Consider what happened with boreal caribou.

An alarming decline in the population of the boreal caribou, possibly related to oil and gas extraction in northeastern BC, prompted the BC government in 2011 to create a recovery plan. The federal government had declared the boreal caribou a threatened species. The plan included increased rules that energy companies should follow in order to protect the caribou herds. But an audit that looked at how o&g activities around the Fort Nelson area stacked up against the new rules, found that companies repeatedly broke the rules – including constructing well pads too large, and building roads in long, straight lines that allow wolves to easily spot the caribou. The audit was submitted to the Oil and Gas Commission, which sat on it for four years; a copy was passed to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), which went public with it.

The BCGEU said the case is an example where whistleblower protection is necessary for workers who speak out in the public interest.

The government-workers union also noted the Oil and Gas Commission’s conflicting mission statement, which both supports resource development and aims to safeguard the environment, could put commission staff in a conflict of interest. Read the full mission statement here

Compare the BCOGC and the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER). The BCOGC claims to be independent but it is a Crown corporation whose chair is the Deputy Minister of the Ministry of Energy, Mines & Petroleum Resources. If the ministry’s mandate is to promote oil and gas extraction, as it undoubtedly is, why is the chair of the regulator a Deputy Cabinet Minister?

In the AER none of the board of directors is a member of government. The agency’s mission statement is also subtly different from the BCOGC: “As Alberta’s sole regulator of the energy industry, the AER keeps energy companies in check as they develop resources across the province.” As opposed to “ensuring responsible resource development” in the BCOGC mission statement.

Alberta traffic lights

Alberta needs to be concerned about fracking-caused earthquakes too. In a paper published earlier this year by the Alberta Geological Survey, author Ryan Schultz writes that hundreds of quakes have occurred around the Duvernay oil and gas field since 2013. The largest was in January 2016 with an earthquake measuring between 4.2 and 4.8, shaking homes in the community of Fox Creek.

Ryan’s research team added two more factors to Kao’s assessment of how fracking causes earthquakes: the underlying rock needs a fault line, and the fault has to be oriented in a direction that can slip. Ryan agrees with Kao, the research scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, that the more fracking fluid is injected, the higher the risk of more and larger earthquakes.

“You could put a nice straight-line relationship between the number of earthquakes you get and the injected volume,” Schultz told Canadian Press. “The more volume you put into the ground, the more earthquakes you get, the more likely you are to get a big one.”

Another study by the University of Alberta found that between 2013 and 2016, 250 seismic events over magnitude 2.5 within 100 kms of Fox Creek were detected. Between 2010 and 2013 there were less than 10.

While in BC, oil and gas companies are required to shut down fracking operations if there is an earthquake 4.0 or higher, in Alberta the AER’s reporting system is more fine-tuned. It’s known as the “traffic light protocol”. Companies have a green light for a quake lower than 2.0, ones between 2.0 and 4.0 get a yellow light caution, and a major quake over 4.0 gets a red light. If a red light is triggered, like in BC the operation must immediately shut down.

The point is, the system in BC appears to be much more skewed towards industry, and less transparent. In BC, only if the fracked well triggers a 4.0 earthquake – which is not small – does the company have to flag it. Anything below passes un-noticed by the regulator. And as we shall see below in the section on dams, BC has a lot more infrastructure to be worried about than Alberta, yet their earthquake reporting system is more stringent.

Fracking in the US

Of course, the phenomenon of fracking-caused earthquakes is not confined to BC and Alberta. In the United States there have been frequent reports from some of the main shale oil and gas basins.

According to Scientific American, worries about the seismic effects of fracking were apparent as early as 2001, after small earthquakes were noticed following intensive drilling in the Marcellus and Utica shale formations, which underly Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York State.

The Ohio Department of Natural Resources said fracking may have produced a 3.0 tremor in Poland Township, 70 miles southeast of Cleveland – high enough to suspend drilling and fracking. Earthquakes tied to oil and gas exploration have also rattled residents of Oklahoma. A 2011 earthquake registering 4.0 shook Youngstown, on the border between Ohio and Pennsylvania. Geologists linked the seismic event to the disposal of drilling wastewater underground.

BC seismicity

Back to BC, it’s not surprising to see evidence of fracking causing earthquakes, considering that one of the conditions for the phenomenon is when drilling occurs in areas where tectonic plates are under pressure.

Most BC residents are aware that the south coast is particularly vulnerable to earthquakes – where the Juan de Fuca plate is pushing against the North American plate – but they may be surprised to learn that northern BC is also seismically active.

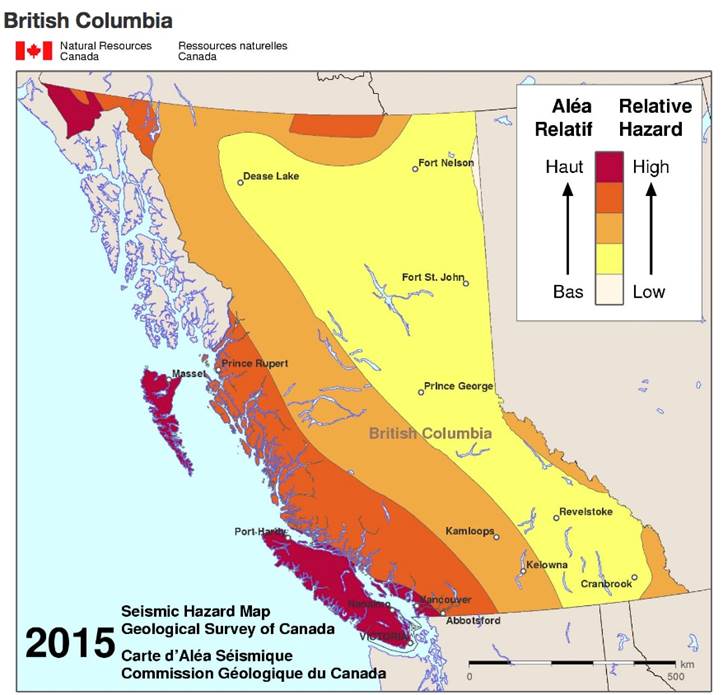

A seismic hazard map from Natural Resources Canada shows the probability of shaking likely to cause significant damage. In the yellow area including oil and gas country in northeastern BC there is a 5 to 15% chance that significant damage will occur every 50 years.

The Northern Cordillera region north of 60 degrees latitude is considered one of the most seismically active areas in Canada. The largest earthquake was a magnitude 6.9 shaker that occurred on December 23, 1985 in the Mackenzie mountains of the Northwest Territories. Six-plus magnitude quakes have also been recorded in the Richardson mountains of the Yukon territory.

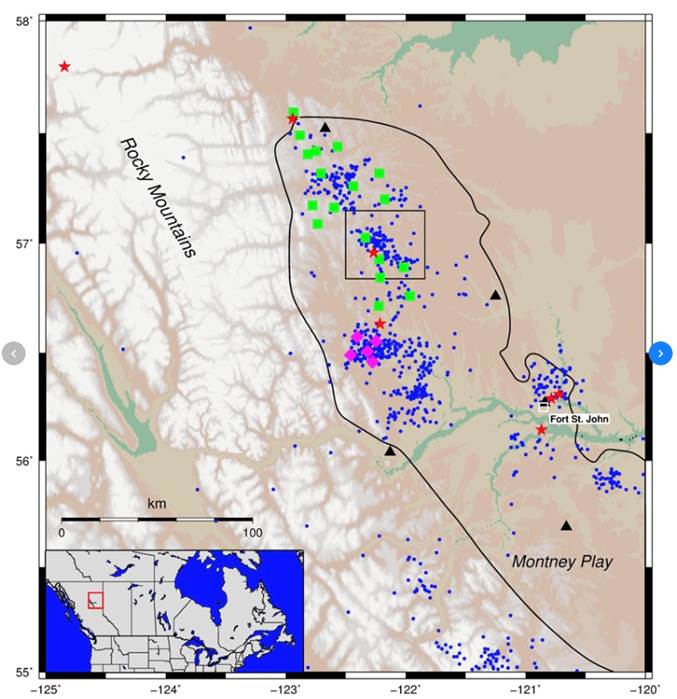

The map below shows the seismicity of northeastern British Columbia from 1985 to 2016. The dots represents seismic events and the stars show earthquakes of 4.0 and higher. The area within the black outline is the Montney gas play, by far the largest source of natural gas in British Columbia.

A football-shaped diagonal that starts in BC and extends 130,000 square kilometres into northwest Alberta, the National Energy Board estimates the Montney contains 90 million barrels of oil equivalent, most of it natural gas. It is comparable in size to the major shale gas plays in the United States, including the Marcellus, Utica and Eagle Ford.

Output from the Montney currently represents a third of Western Canadian gas production, which is double the output since 2012. By 2040 the National Energy Board thinks more than half of Canadian gas will be coming out of the formation; most if not all of the gas required to feed LNG compression plants will be fracked from the Montney.

Threats to dams

British Columbia’s volcanic history – being part of the Ring of Fire that arcs from southern California all the way to Alaska – has endowed it with some of the most mountainous, pristine terrain in the world. This has blessed the province with an abundance of fast-flowing rivers that provide hydro-electricity for its nearly 5 million residents.

The longest river is the Fraser, which drains into the Strait of Georgia near Vancouver. Other rivers of note include the Columbia, Peace, Stikine, Nass, Skeena and Kootenay. According to BC Hydro, 80% of its installed generating capacity is in the Columbia and Peace river basins.

The Columbia region contains four large hydroelectric dams (Revelstoke, Mica, Seven Mile Generating Station, Kootenay Canal), seven small hydro dams, and two storage dams that don’t generate power (Hugh Keenleyside, Duncan).

The Peace region has two large dams, the Peace Canyon and the W.A.C. Bennett dams. The latter also has the Williston Reservoir, the seventh largest water impoundment in the world, covering 1,773 square kilometers. Built in 1968, the Bennett dam is the height of a 60-storey building and 2,068m long at its crest. The Peace River flows out of the eastern edge of Williston Lake through the Peace River Canyon.

Now over half-way through its expected 100-year life, the Bennett dam was intensely scrutinized in the mid-1990s when two sinkholes appeared at its crest. According to an article in BC Business Magazine, were the dam to fail, it would wipe out the Peace Canyon Dam downstream, sending a 135-foot wall of water much further downstream, flooding the entire Peace River Basin and communities as far north as Forth Smith, NWT. The damage would be more catastrophic than any natural disaster western Canada has ever seen:

Unlike a tsunami, the destruction wouldn’t simply peak and stop. The pent-up waters of Williston Lake would just keep coming, seeking to return to its natural elevation. The waters would flow for weeks, scouring away communities like Old Fort, Taylor, Peace River, Fort Smith and beyond. The onslaught would back up tributaries and inundate the entire Peace River Basin, flooding Lake Athabasca and Great Slave Lake. The floods could devastate northern Alberta, portions of Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories all the way to the Arctic Ocean. The death toll could be high; the environmental and structural damage astronomical. Combined with the loss of generating power of the dam, the unprecedented disaster would cost billions of dollars and throw B.C.’s economy into turmoil.

Now consider that the W.A.C. Bennett Dam and the Site C Dam currently under construction, are earth-filled dams that are not build to withstand major earthquakes – including ones caused by fracking for natural gas.

How vulnerable are the Peace River dams to northeastern BC oil and gas operations? The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives has done extensive research on this topic. Here are its major findings:

- Documents released by BC Hydro under Freedom of Information (FOI) showed that Hydro officials in 2009 became alarmed at a coal-bed methane operation near its Peace Canyon Dam. BC Hydro’s former chief safety, health and environment officer, Ray Stewart, warned that the “potential effects” of such actions could be natural gas industry-induced earthquakes that were greater in magnitude “than the original design criteria for the dam.” Stewart also warned that fracking could reactivate ancient faults. The industry has since moved on from coal-bed methane fracking to fracking shale gas, which requires even more forceful injection of water, sand and chemicals.

- Between 2010 and 2013, 12 earthquakes were recorded near BC Hydro’s Peace River dams, corresponding with fracking for shale gas.

- There are two faults running beneath the Peace Canyon Dam. The geology is similar to California’s Baldwin Hill Dam breach in 1963 that spilled 292 million gallons into a community, destroying hundreds of homes and killing five people. Oil and gas production may have contributed to the dam failure, according to BC Hydro.

- Ground movement from fracking could alter weak bedrock and change the way water naturally seeps through earth-filled dams.

- An “unwritten understanding” exists between the BC Oil and Gas Commission and BC Hydro that no new tenures should be awarded to companies that want to access natural gas deposits within 5 km of the Peace Canyon, Bennett and Site C dams. However companies already holding these rights will be grandfathered in, allowing them to frack. In contrast Alberta has shut down fracking with 5 km of one of its dams and also around the reservoir. There are also restrictions on fracking up to 10 km away from the dam site.

- Limiting where companies drill and frack is not part of the OGC’s mandate, according to Gordon Campbell’s former chief of staff.

- Earthquakes from fracking occur closer to the surface than natural earthquakes, putting dams and other major infrastructure at risk.

- Only one piece of infrastructure in BC places limits on fracking, and it’s not a dam: a natural gas reservoir near Pink Mountain, with a capacity for 77 billion cubic feet of natural gas. The facility is considered critical for expansion of LNG. The owner, Chevron, met with Fortis BC and the provincial government to establish rules that ensure that drillers are aware of the facility and do not extract gas from the reservoir or do anything that might jeopardize its integrity.

- At least 92 unauthorized dams have been built in northeastern BC, to be used exclusively by oil and gas companies for the purpose of fracking; 41 were built without proper licenses and authorizations; all 41 are on private lands including farmland. Nearly a third of the 92 dams were found to have structural problems including a lack of spillways. No companies have been fined for violating the rules.

- A 2016 analysis found that fracking operations in the region consume between 20 and 100 times more water than a decade ago. The need for more water is due to high-volume fracking; much greater amounts are injected deeper, because shallower shale gas has already been tapped.

BC LNG: Way more risk than reward

John Horgan and the BC NDP estimate the LNG Canada project will generate $22 billion in revenue over 40 years. We already know from a previous article that the net benefit will be much lower, maybe even negative, when the real costs of LNG are tallied up.

Some of these costs will stem from an acceleration of fossil fuel emissions from the conversion of natural gas to LNG (natural gas is cooled to 163 degrees below zero using massive compression units running 24/7), and fugitive methane emissions from natural gas fields, primarily the Montney play where most of BC’s remaining natural gas is left.

These increased emissions will: accelerate the melting of Arctic sea ice, triggering a high-pressure system over BC throughout the summer, which causes extended no-rain periods, lightning and forest fires; hasten a feedback loop due to the melting of permafrost, causing more methane to be released; cause landslides and the re-activation of extinct volcanoes like Mt. Meager near Squamish due to melting glaciers exposing methane events and cracks that, with constant melting and freezing, eventually cause mountain-sides to slip.

More LNG tanker traffic along the BC coast will also quicken the extinction of killer whales and deplete populations of other cetaceans that use sonar to find food; Washington State is considering imposing a three to five-year ban on whale-watching tours to help protect endangered orcas.

This new BC LNG industry will also allow mostly foreign companies to pump, and destroy, billions of gallons of free fresh water, by fracking natural gas wells.

Each well uses between 1.5 million and 15 million gallons (American Geosciences Institute) of locally-sourced fresh water (an estimated 28,000 wells have been drilled so far in northeastern BC – that number could easily double), which will be permanently contaminated by toxic chemicals contained in the fracking fluid, in ground contaminants, and the mixing of the two to create new toxic substances. This is water that could be used for drinking, by animals or humans, or for irrigating crops and pastures.

In some areas where fracking occurs, there have been increases in other hazardous pollutants besides methane – namely particulate matter and ozone. Living under half a mile from an unconventional gas well puts you at greater risk of respiratory symptoms, cardiovascular disease and cancer, according to one study quoted by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

On top of the methane gas escapes and other toxic emissions, methane in the water, ruined fresh water that could be put to productive and healthy uses, there are dangerous health risks including benzene poisoning leading to cancer and birth defects. We already know from a 2017 study that fracking releases volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like benzene into the environment. Urine samples of 29 pregnant native women living near fracking operations in northeastern BC measured two “biomarkers” that our bodies produce when we’re exposed to benzene, a carcinogen that’s been linked to low birth weights and some defects.

Then there’s the risk to dams from fracking explained above, which BC Hydro and the BC government have known about since 2009 yet continue to turn a blind eye towards, as witnessed by the BC Oil and Gas Commission failing to enforce regulations around illegally-built small dams and other rules broken by oil and gas companies.

Granted, BC Hydro says it’s investing $1.9 billion in dam safety and seismic upgrades. We can subtract that from the $22 billion in LNG revenues, to get the net benefit. Are the dams in northeastern BC being seismically upgraded to withstand a 4.6 earthquake like the world record-breaking one from a fracking operation in 2015? Nobody knows, because this information is not publicly available. Just about everything we know about BC Hydro and dam safety has been ascertained through FOI requests.

What would it cost the province if one of the Peace River dams failed? We know that the breach of the Mount Polley Mine tailings facility in 2014 cost taxpayers almost $40 million to clean up. And that was without any damages to homes or loss of human life. It would certainly be in the billions.

We also need to look at where our BC gas is going. What are we getting out of LNG for assuming most of the risks?

Methane – the largest component of dry natural gas – used to be the mainstay of BC oil and gas production, but it has been supplanted by higher-value gas liquids.

With natural gas prices remaining low due to the glut of North American gas from fracking, profits in the Montney play now come almost entirely from “wet” gases that flow to surface along with dry gas following fracking.

The most important liquids are pentane and condensate, used to dilute bitumen – the thick crude oil that is liberated from oilsands. These fluids are used to dilute bitumen so it can flow through pipelines. The majority of BC wet gas goes to the Alberta oilsands.

According to research by the CCPA’s Ben Parfitt, in 2007 oil and gas companies produced 2.97 million barrels of condensate. This year it’s close to 20 million barrels. The net profits on each barrel are around $53 (Western Canadian Select crude is currently sold for $26.15). That’s because shipping costs are so low, due to the short distance between the Montney Basin and the oilsands.

How much of that goes into BC coffers? Not much. The province heavily subsidizes natural gas producers, by offering generous discounts on royalties.

Quoting a former market analyst for the BC Energy Ministry, the CCPA article states that in the last 10 years, “the difference between the gross royalty charges to companies drilling for natural gas and gas liquids in northeast BC versus the net royalty payments they actually made was close to a combined $5 billion.”

Multiply that by four and you get $20 billion given away over the next 40 years.

Now consider that BC’s natural gas producers, like their oil company counterparts, want a natural gas pipeline from the Montney to Kitimat – the future site of LNG Canada’s compression plant – so they can receive higher prices for their natural gas and ship it to Asia.

Yet before a shovel has even been put in the ground for the new Coastal GasLink pipeline, BC’s government has already granted nearly $6 billion in tax breaks to the LNG Canada consortium over 40 years. Knock that off from the $22 billion too, since it’s foregone revenue.

Is this looking like a good deal for BC residents? Absolutely not.

Conclusion

In British Columbia we live in an earthquake zone. Though many of us have never felt one, the Earth below is constantly on the move. Talk of “the big one” somewhere off Vancouver Island has become so frequent that people have tuned out. They might tune back in if they knew how much fracking activity is taking place in the remote northeastern corner of the province and how much risk this activity is posing to dams. This risk is only going to increase when the Site C dam is built and the number of fracking wells doubles or triples, depending on how many LNG projects are approved. BC Hydro says we need at least three.

We need to add the catastrophic costs of a major dam breach to the already skyrocketing “real” costs of developing an LNG industry here, at exactly the wrong time, when the effects of climate change are stacking up year by year. But the politicians aren’t listening. They’re salivating over $550 million a year, which, by the way, isn’t a lot. For context, the last BC budget allocated $450 million to a student housing program.

Compare that half a billion dollars a year to the annual impacts of a renewed push to develop fossil fuels in this province. The unimaginable costs of a potential dam breach, and the very measurable costs of poisoned groundwater, deaths and hospitalizations due to fracking, elevated greenhouse gas emissions, wildfires, melting glaciers, landslides, the extinction of top-of-the-food-chain killer whales, the list goes on and on.

LNG in BC? It’s just not worth it.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd is on Twitter

Ahead of the Herd is now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd is now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.