Our dystopian future is already here – Richard Mills

2024.03.09

Global heat records keep getting smashed, as a combination of global warming and El Nino cook the Earth’s surface and warm its oceans, affecting marine life and causing extreme weather, including heat waves, intense rainfall and hurricanes.

It was the hottest February ever, marking the ninth straight month that global heat records have fallen, CNN reported on Wednesday, March 6.

Copernicus, the European Union’s climate monitoring service, found that last month was 1.77 C warmer than the average February in pre-industrial times. February also capped off the hottest 12-month period in recorded history, at 1.56 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

CNN said experts are shocked at how hot the oceans have been, with global sea temperatures hitting 21.06 degrees in February, the highest of any month on record.

“At times, the records have been broken by margins that are virtually statistically impossible,” Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School, told CNN.

In the North Atlantic, a new daily temperature record has been set every day since March 5, 2023.

Global Warming has a major impact on agricultural commodities that are affected by droughts and flooding.

Droughts are impacting food production in Canada and the United States, lowering crop yields, and causing ranchers to cull their herds. The war between Russia and Ukraine led to record-high fertilizer prices in 2022, passed on to consumers in dizzying food price hikes.

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

A 2021 study showed more than a fifth of global food output growth has been lost to climate change since the 1960s, putting an estimated 34 million people on the brink of famine.

Drought

An abnormally dry winter in Western Canada is worsening drought conditions after an already bad 2023. Last year was the country’s hottest on record — a combination of global warming and the start of the El Nino climate phenomenon, which is weakening but continues.

John Pomeroy, a hydrologist at the University of Saskatchewan, said low mountain snowpack, early melt then extreme heat, high evaporation rates and lack of summer rainfall were the “ingredients in the climate kitchen” that contributed to drought last year.

“We’ve never seen a hydrological year quite like this in Western Canada,” Pomeroy told The Weather Network:

As Pomeroy says, 2023 saw “some of the lowest stream flows ever recorded” on water systems like the Bow River, record wildfire seasons in Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan thanks to dry conditions, water use restrictions in major cities, shrinking water reservoir levels, early irrigation shutdowns and low agricultural yields in some parts of Alberta as communities across the province declared agricultural emergencies. In its December 2023 drought assessment, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada declared 70 per cent of the country “abnormally dry or in moderate to exceptional drought,” including 81 per cent of Canada’s agricultural landscape. Hydropower production was also affected in Manitoba and British Columbia.

Pomeroy’s University of Saskatchewan research team also recorded record-high ice melt in the Columbia and Wapta icefields, which could lead to longer-term water supply issues.

Reuters said many cities experienced their warmest December ever recorded. As of Dec. 31, 70% of the country was abnormally dry or in drought, according to Agriculture Canada, with the worst conditions in southern Alberta, western Saskatchewan and north-central British Columbia.

Virtually all of the Prairies have received less precipitation than normal during the past 60 days as of Jan. 8, with large stretches of each province collecting less than 40% of usual precipitation.

As of mid-January, British Columbia’s snowpack was on average 44% below normal, and there are worries about low reservoir levels and a repeat of the disastrous 2023 wildfire season (more on that below).

There are long-term water deficits across western Saskatchewan from North Battleford to Leader, and in Manitoba, though drought conditions improved in December, the province remains vulnerable due to extensive drought across the prairies.

But the driest places in Canada are in Alberta.

According to Reuters, three years of drought have raised the cost of feeding cattle and drained dugouts that the cattle drink from. This has forced some farmers to reduce their herds. Canada’s cattle inventory hit its lowest level on record in 2022, according to Statistics Canada.

Farms in southern Alberta depend on irrigated river water to sustain crops of potato and sugar beet. Non-irrigated Prairie farms produce most of Canada’s wheat and canola, much of which are exported.

Things have gotten so bad, the Alberta government has drafted an emergency plan to deal with drought in 2024. A “drought command team” will work with water license holders to develop new ways to share and manage water in the year ahead, states The Weather Network, adding more than 20 Alberta municipalities declared agricultural emergencies in 2023.

In the United States, millions of Americans across a wide swath of the Midwest, East Coast and South enjoyed summer-like temperatures in February. According to the National Weather Service, last month was the warmest on record for Chicago, which saw an average 49.2 degrees, 13.5 degrees above normal. A record daily maximum of 71 degrees was set on Feb. 26.

Philadelphia, Cleveland and Houston all set monthly (daily) highs of 64 degrees on Feb. 27. Temperatures rose above 90 across portions of Texas on Feb. 25 and 26.

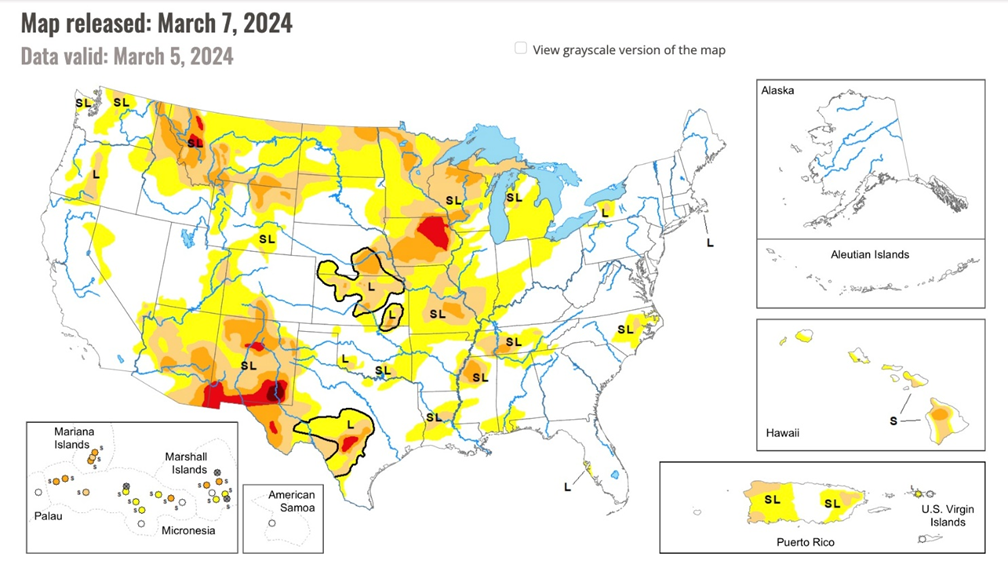

According to the Boise, Idaho-based Interagency Fire Center, temperatures were well above normal across the central and northern Plains into the Midwest for February, with the most extreme anomalies of greater than 15 degrees above normal over portions of North Dakota and Minnesota. Above normal temperatures also extended into the northern Rockies, southern Plains, Lower Mississippi Valley, Appalachians, and Northeast,

Precipitation was below normal across much of the northern Plains through the Midwest into the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. Below normal precipitation was observed across portions of west Texas, western Oregon, Washington, and northern Idaho.

Extreme to exceptional drought persists in southern New Mexico, with extreme drought also in portions of eastern Iowa and northwest Montana. Drought developed in portions of the Upper Midwest and northern Rockies.

Source: U.S. Drought Monitor

Water

With drought extending across much of Western Canada and the southwestern US, availability of fresh water is a major concern.

From late August to early December, three communities in southwestern Alberta had to haul in water, due to levels in the Oldman Reservoir so low (28%) that the intake pipes were exposed. At that time of year, the reservoir would normally be at 62-80% capacity.

Residents also faced sharp usage restrictions.

Indications are that this year could be worse.

On Jan. 31, the province’s environment minister Rebecca Schultz sent a letter to all 25,000 holders of water licenses in Alberta, launching negotiations to get users to reach water sharing agreements, CBC News reported.

Besides the Oldman Reservoir, other water catchment areas are failing to fill up due to lower than normal snowpack and river flows. As of Feb. 1, St. Mary’s Reservoir was at 15% when it should be between 41 and 70%, Willow Creek near Claresholm logged its lowest monthly flow since 2000, and the Peace River saw the lowest average flow this century. Groundwater by Kananaskis’ Marmot Creek is at its lowest levels in more than 50 years.

Above-mentioned John Pomeroy said the combination of El Nino and ongoing global warming means it’s unlikely that Alberta will see sufficient snow or rainfall to ward off drought conditions.

Municipal Affairs Minister Rick McIver predicted that trucked-in water and urban water restrictions will likely be necessary again this year.

In British Columbia, large parts of the province are suffering drought conditions the federal government has called extreme. In eastern BC, the village of McBride’s reservoir ran dry last summer, forcing residents to ration water. Glaciers have receded and no longer feed the town’s watershed.

Snowpacks in BC last month were 39% below normal. Recent chinooks in Alberta were warm enough to melt snow above the tree line.

There are currently calls to bring in water metering across the province. According to Global News, Despite recent rain and snow, data from the federal government found most of the Pacific region was under drought conditions as of the end of February, while the latest snowpack monitoring shows much of B.C. well below average…

The B.C. government earmarked $50 million for water metering pilot projects in 21 communities, which would bring them in line with cities like Victoria and West Vancouver that already use water metering systems.

Saskatchewan’s main water supply from Regina’s Lake Diefenbaker is meters below average for this time of year, and in other parts of Canada the groundwater is depleted, meaning water users have to pump from further down.

Toronto typically gets around 80 millimeter of rain or snow in February, whereas this year it only received 3 mm of rain.

Yet the water situation is far worse in the United States.

In 2020, the federal government declared a water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time, triggering mandatory water consumption cuts.

Lake Mead, America’s largest manmade reservoir, and a source of water for millions, in 2022 fell to an unprecedented low.

According to research by Colorado State University quoted by ABC News, nearly half of the 204 freshwater basins they studied in the United States may not be able to meet the monthly water demand by 2071.

Hydroelectric dams and nuclear power plants are both highly dependent on water supplies to generate energy.

In the southwestern US, dams on the Colorado River provide electricity to 5 million people, but water levels in the reservoirs have been falling for decades.

Further downstream, diminished annual generation at the Hoover Dam has started a conversation about a potential “deadpool” situation.

Nuclear power plants are also feeling the effects of diminished river levels. A researcher at the University of Washington found that nuclear and other power plants will see a 4 to 16% drop in production between 2031 and 2060 due to climate-induced drought and heat. (InsideClimate News)

An Associated Press analysis quoted by NBC News states that of the United States’ 104 nuclear reactors, 24 are in areas experiencing the most severe droughts. Submerged intake pipes draw billions of gallons of water used for cooling and condensing steam after it has turned the plant’s turbines.

For nuclear power plants, it isn’t only the danger of water running low, but of water getting too hot. Water is normally used to cool the reactors before it is released into the river. But overheating can threaten fish and other wildlife.

Closer to home, Reuters said BC Hydro’s largest water reservoirs in the province’s north and northeast are below normal. Last year, the utility had to import 10,000 gigawatts of electricity, about 20% of its total energy needs — much of it from Alberta and western US states.

Another hydro-dependent province, Manitoba, is also experiencing alarmingly low reservoirs that are negatively impacting electricity production. According to The Narwhal, since October, Manitoba Hydro has been periodically supplementing hydro production by firing up its natural gas-fired turbines. Typically, it uses these only in the depths of winter to offset peak demand…

Manitoba Hydro is already projecting a financial net loss for the current fiscal year — only its second in the past decade, with the other being in 2021.

Ironically, “green” hydroelectric and nuclear power are becoming victims to rising temperatures that dry up their water sources. This is happening at exactly the wrong time, as electricity demand ramps up due to the growing importance of electric vehicles and decarbonization.

Manitoba Hydro’s own modeling shows electrical demand in the province could more than double in the next 20 years, and new sources of electricity could be needed in the province within the next decade, states The Narwhal.

Fires

Arguably, the scariest result of heat, drought and water shortages is the potential for wildfires.

The reason is obvious: reduced snowpack and less-than-normal precipitation dry out the ground and make it more susceptible to human- or lightning-caused ignitions.

The Alberta government in February declared the start of the wildfire season, 10 days earlier than the normal March 1.

Last year was Canada’s worst forest fire season on record, with roughly 18.5 million hectares burnt. This year will likely see a repeat.

“I think that we will probably have a very bad fire season. And that’s all the way from the West Coast, right through northern Ontario, northern Quebec and even into parts of the Maritimes,” Global News quoted John Richardson, a professor at UBC’s department of forest and conservation sciences.

State-side, fire activity was low across the US at the beginning of February, but increased significantly across portions of the Rocky Mountain, Eastern, and Southern areas in the latter half of the month, according to the Interagency Fire Center’s ‘National Significant Wildland Fire Potential Outlook, March through June 2024’:

The Eastern and Southern geographic areas increased to preparedness level 2 (on a scale of 1-5) on February 26 due to increased fire activity, with Southern Area increasing to preparedness level 3 on February 28, with dozens of large fires burning in the Southern Area at the end of the month. Year-to-date annual acres burned for the US is well above the 10-year average near 135%, but with a below average number of fires, near 92%…

Above normal significant fire potential is forecast for portions of the central and southern High Plains in March and April, as well as the Eastern Dakotas, Upper Midwest, and southern Missouri. These areas will return to normal potential in May, but potential will increase to above normal in the lower elevations of the Southwest into West Texas in May and June. Above normal potential is forecast for the lee sides of Hawai’i in May and June as well…

A strong westerly wind event coupled with low relative humidity February 25-26 triggered a fire outbreak across the central and southern Plains from Nebraska to Texas. Several new and significant fires began during this outbreak including the Betty’s Way Fire near North Platte, Nebraska and the Smokehouse Creek and Windy Deuce Fires in the Texas Panhandle.

While forest fires aren’t top of mind during winter, it may be surprising to learn that some never go out; they continue to smoulder underground, in what are known as “zombie fires”.

As of Feb. 27, there were 50 fires burning in Alberta, most of them never extinguished after the infernos of 2023, states National Observer. Next-door British Columbia had 92 fires.

On the map below, the orange dots are the “Under Control” zombies sized 1 to >1,000 hectares. The underground blazes are especially prevalent in areas with lots of organic material in the soil, such as duff, litter, roots and buried logs. Fires that get into that dry, buried material can with a little bit of oxygen burn for months, even years.

In Fort Nelson, BC, residents observed clouds of smoke rising from the ground, mingling with the falling snow.

“I’d never experienced a snowstorm that smelled like smoke,” Sonja Leverkus, a firefighter and scientist, told the BBC.

Opinion writer Chris Hatch quoted author John Vaillant, who in his book ‘Fire Weather’ states, “There is in our future a potentially winter-less scenario in which fire weather is the only weather, and ‘fire season’ never ends.”

Premier David Eby says he is “profoundly worried” about another potentially terrible wildfire season in BC. The province has set aside $10.6 billion in contingency funds over the next three years.

Food inflation

Water shortages could force Alberta ranchers to again downsize their cattle herds. In recent years, drought conditions in Canada and the United States mean ranchers can’t grow enough feed for their livestock.

When an entire industry faces the same quandary, more cattle sent to slaughter, prices temporarily decline. But shortly the excess slaughter works through the market. A 10-ounce New York steak three years ago cost $15; today it’s around $20, beef prices could easily double from here.

CBC News reports that 2023 saw Canada’s beef inventory fall by 1.5% to 3.66 million animals, the lowest since 1989. South of the border, the national cattle herd has been contracting for five years, reaching just 28.2 million animals last year, the fewest since 1961.

Higher beef prices are likely here to stay, at least for awhile. CBC Notes even if the current drought cycle were to end this year, cattle numbers can’t rebound overnight. Consumers need to understand these cattle herds have been raised for generations by ranchers to provide the best and most meat off each carcass. These bred in generational genetics will be lost in the new herds, it’s almost like ranchers will be starting over in their breeding programs.

Of course, there are many other foods impacted by droughts, flooding and other manifestations of global warming.

In BC’s Okanagan region, orchardists and vintners say their vines and trees were severely damaged this winter, when a December warm spell was followed by bitter cold.

The global impact of global warming on food prices cannot be understated. The warming is influencing weather patterns, causing heat waves, heavy rainfall, and droughts, making it difficult to grow crops in many parts of the world year after year.

Last year in the western United States, droughts and wildfires led to lower-than-average crop yields. According to the World Bank, about 80% of the global population most at risk from crop failures and hunger from global warming are in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, where farming families are disproportionately poor and vulnerable. A severe drought caused by an El Nino weather pattern or climate change can push millions more people into poverty.

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia, a major oil and gas producer, and the world’s largest exporter of wheat, in 2022 added to higher grocery bills, and record gasoline prices.

Many emerging market countries rely on food imported from Ukraine and Russia – known as ‘the breadbasket of Europe’ due to the region’s abundance of grains like wheat, barley, corn and soybeans.

Transport issues are further compounding food security concerns.

Water levels on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers in 2023 fell for a second straight year, raising the prospect of shipping problems on crucial freight routes.

In December, low water levels in the Panama Canal, fueled by drought, forced the canal authority to reduce the number of vessels transiting daily. Rain suspended further restrictions but they could be reinstated in April, when the authority re-evaluates water levels.

Another global choke point, the Suez Canal (and the Bab al-Mandeb Strait), is vulnerable to supply chain interruptions. Late last year, more than 100 container ships were rerouted around southern Africa to avoid the Suez Canal, where Houthi rebels were attacking vessels off the coast of Yemen. The attacks were in support of Hamas, which carried out a deadly invasion of Israel in October, prompting Israel to counter-strike the Gaza Strip.

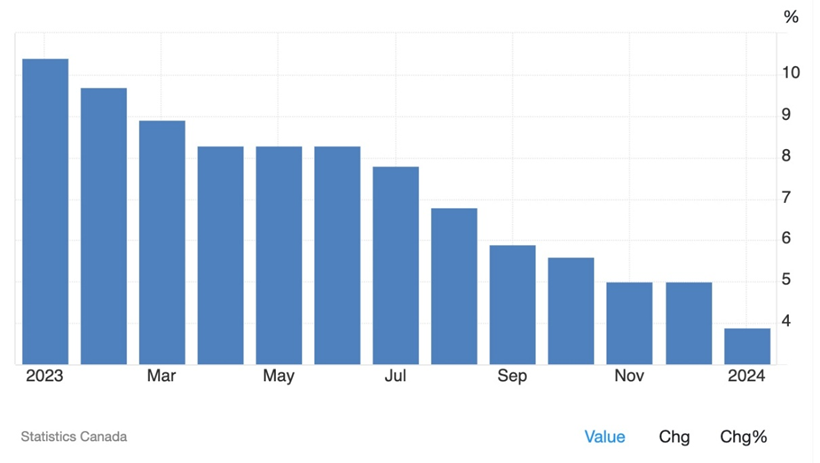

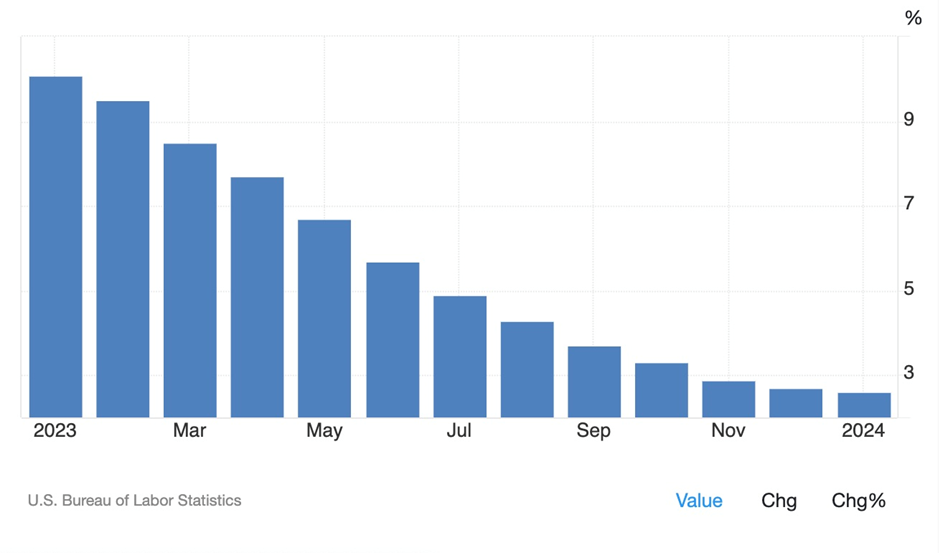

While food inflation in Canada and the United States has come down, prices are still higher than they were before the pandemic which started in early 2020.

Oxford Economics sees global food prices remaining 25% higher than during the pre-pandemic decade.

The World Economic Forum identifies four foods that are more susceptible than others to inflation, brought about by global warming and supply issues caused by events like the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. They are cocoa, olive oil, rice and soybeans.

In February 2024, cocoa prices hit a record high as crops in West Africa were impacted by dry weather.

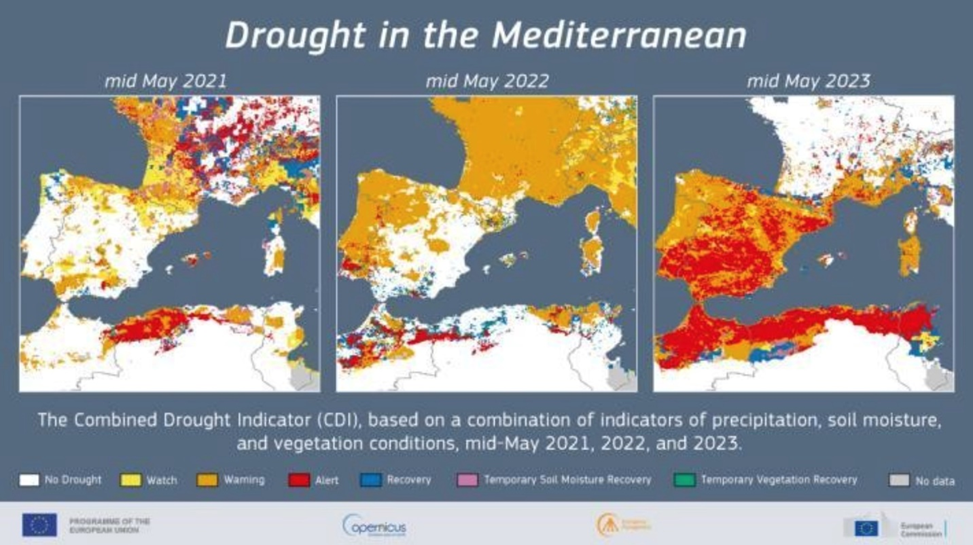

A hot dry summer in the Mediterranean damaged olive trees and caused a poor crop. Olive oil prices soared to a record high and stock piles are significantly down from previous years.

Rice farmers from Italy to India have been feeling the effects of climate change for years. It’s not only drought, but flooding and saltwater intrusion (caused by rising sea levels and overuse) that is ruining crops.

Italy, which grows about half of the European Union’s rice, warned one year ago that rice output would fall due to a second year of drought.

In Asia, rice prices hit their highest levels in two year last July, on concerns the dry weather would damage crops. India had the opposite problem. Heavy monsoon rains damaged the rice crop, causing the country to halt some categories of rice exports.

Prices surged to a 15-year high in August, and according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, in October 2023 rice was 24% higher than the previous October.

The arrival of El Nino further tightened the rice market. According to Economic Times, paddy output from Thailand, the number two producer, is likely to fall 6% in 2023-24. Rice inflation in the Philippines soared to a 14-year high in September.

In December the World Bank predicted, “Rice prices will remain high into 2024, assuming India maintains its export restrictions. The outlook assumes a moderate-to-strong El Niño.”

In 2023, the US Midwest experienced the worst drought since 2012, impacting soybean production. Only an estimated 4.16 million bushels were produced in the country last year, a drop of almost 106 million bushels compared to 2022.

Drought in another large soybean producer, Argentina, caused output to crater 27% between January and August 2023, its lowest level since 2015.

Conclusion

As the planet continues to warm, and populations are forced to migrate from worst-hit areas there will be increased competition for resources, whether it be housing, jobs or food.

In 2019, US News reported on a research paper which found that intensifying global warming will likely increase the future risk of violent armed conflict within countries.

The researchers agreed with us, at AOTH, that mass displacements of people forced to leave areas that become inhospitable, increase the possibilities for conflict.

A more recent article by Al Jazeera says that climate change is already causing human rights emergencies around the world. It quotes UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Turk:

“This spiralling damage is a human rights emergency for Iraq and many other countries,” Turk told the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva on Monday.

“Climate change is pushing millions of people into famine. It is destroying hopes, opportunities, homes and lives. In recent months, urgent warnings have become lethal realities again and again all around the world,” he said.

“We do not need more warnings. The dystopian future is already here. We need urgent action now.”

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.