Why commodities are sailing into a perfect storm of higher prices – Richard Mills

2023-12-02

While there is disagreement over its causes, the reality of global warming is an incontrovertible fact. The planet is warming, affecting our weather, oceans, growing seasons and food, as crops fail, causing shortages and price hikes. Storms are becoming more frequent and more intense. Droughts are lasting longer. Heat waves and forest fires are now annual summer occurrences.

The heating up of the world’s oceans is one of the most damaging aspects of climate change. The phenomenon is driving weather disasters around the world, including extreme heat, storms and drought.

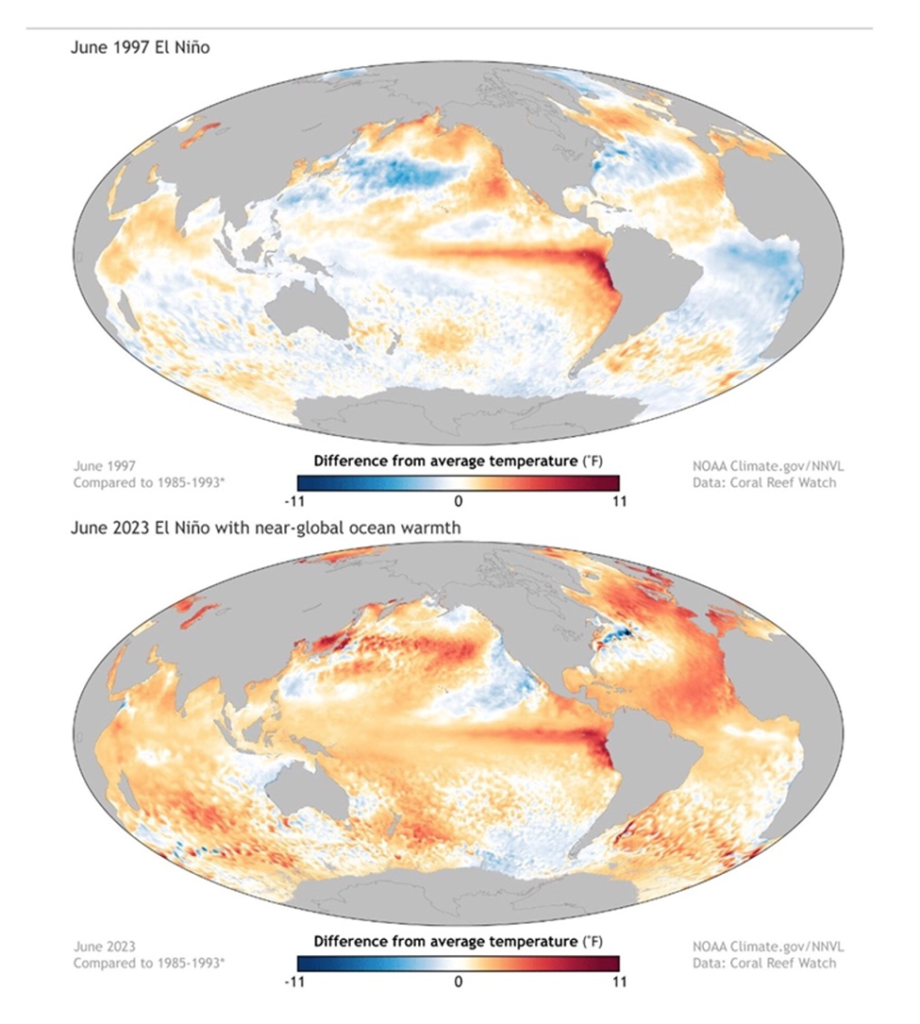

A July media report said Global ocean surface temperatures in June were the highest in 174 years of data, with the emergence of the El Nino weather pattern piling onto the long-term trend. Near Miami, coastal Atlantic waters are pushing 90F (32C).

According to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, the extreme heat wave that blanketed the southern United States and Mexico in June, combined with ocean temperatures soaring to alarming levels.

In Antarctica, scientists have linked warm waters off the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic oceans to plunging sea ice levels.

The Globe and Mail said parts of the continent and nearby ocean were 10 to 20 degrees Celsius higher than averages from 1979 to 2000.

El Nino

Another related climate phenomenon that is behind the record heat, is the switch from “La Nina” to “El Nino”.

It’s been well-established that warmer, or colder-than-average ocean temperatures have an influence on weather. According to the NOAA, El Nino causes the Pacific jet stream to move south and spread further east. During winter, this leads to wetter conditions than usual in the southern US and warmer and drier conditions in the north.

El Nino is shorter-lived than La Nina, usually lasting nine months to a year versus a few years for the cooling phenomenon. El Nino is said to be warming up the eastern Pacific Ocean, and is forecast to intensify and linger to at least the end of the year, resulting in higher global temperatures. The World Meteorological Organization officially confirmed the arrival of El Nino on July 5.

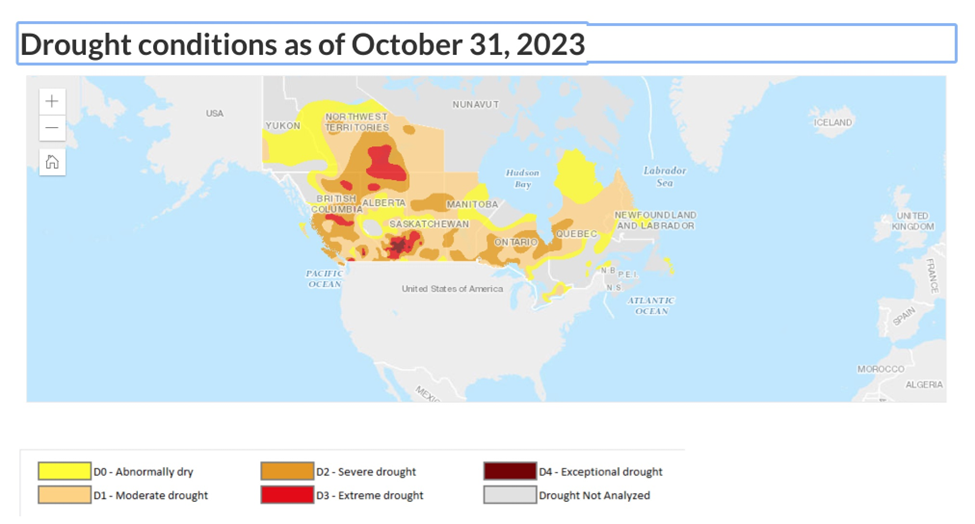

Most forecasters believe that, with El Nino kicking in across the Pacific Ocean, Western Canada could be dry for months, possibly even approaching the parched conditions the southwestern United States has been experiencing for the last 20-odd years.

In particular, the climate phenomenon is expected to have a negative effect on the Prairies, bringing a warmer and drier-than-average winter.

CBC notes the last El Nino, during the winter of 2015-16, Pacific Ocean temperatures rose more than 2 degrees above average, and left the Prairies 4 degrees warmer than normal from December to February. It also left an extreme moisture deficit, especially in southern Saskatchewan and Alberta. Almost none of the Prairie regions received more than half of their average moisture during that time.

The NOAA predicts a 62% chance that El Nino will continue during April through June 2024 — prime growing season on the Prairies.

The CBC quotes an Environment Canada spokesperson saying that El Nino could further complicate things for the Prairies, after a record-breaking forest fire season and intense drought — the region was dry last winter, in the spring and in the summer.

“The whole summer, most of Western Canada was on fire. We went through a dry fall, so coming into another dry winter could be really, really problematic.”

The latest drought data shows most of the Prairies are drier than normal, with parts of southern Alberta experiencing “exceptional” drought, CBC said.

Agriculture

A mixture of continued global warming and the current El Nino cycle would almost certainly set off a ripple effect on the commodities markets, particularly agriculture. This can be directly via weather conditions that impact crop yields, or indirectly by disrupting shipping routes.

We’ve previously highlighted the various reasons why food inflation isn’t going away any time soon. Among those is global warming, which is influencing weather patterns, causing heat waves, heavy rainfall, and droughts, making it difficult to grow crops in many parts of the world year after year.

A study recently published in Nature found that rising temperatures are expected to stall progress on food insecurity by reducing agricultural yields in the coming decades.

In an Economist article, Maarten van Aalst, director of the Dutch meteorological agency and former head of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, said, “We have never had an El Nino on top of so much global warming, so we don’t know what is going to happen.”

“To put it in real perspective, it’s not just the name El Nino that evokes fear among commodity consumers but the intensity of it. This looks like being a very intense one,” said Michael Magdovitz, a senior commodity analyst with Rabobank.

El Ninos have in the past driven down rice yields. For example, in 2015-16 southeast Asia’s crop declined by 15 million tonnes, representing 7% of global stocks. Australia, which produces 12-15% of the global crop, sometimes saw its yields halve during El Nino years.

As of Nov. 30, rice prices are close to hitting 15-year highs, with white rice 50% broken hitting $640 per ton this week. The severe effect of El Nino is damaging farmland across Asia, lowering supplies. Prices are up over 50% since the start of 2022.

Even before El Nino’s arrival, certain staple crops had already been suffering from climate events. Reuters previously reported that rice futures hit an almost 15-year peak in June as India, Thailand and Vietnam, three of the largest exporters of this staple, experienced record or near-record high temperatures.

With respect to the impact of El Nino, more drought could impact Australian grains and Indonesian and Malaysian palm oil, and potentially sugar, cocoa and coffee as well, says Rabobank’s Magdovitz.

Global wheat consumption is forecast at 804 million tonnes in 2023-24, an increase of nine million tonnes over last year. Meanwhile, production is estimated to have fallen to 787 million tonnes, a 7 million-tonne decline, states The Producer. The gap between supply and demand is due to smaller harvests in Canada, Russia and Australia.

Reuters said this week that heavy rain in southeastern Australia has damaged wheat crops, potentially shrinking production by over 100,000 tons and turning up to a million tons of milling wheat into lower-quality grain feed.

Heat and low rainfall earlier in the year cut forecasted production to 25-28 million tonnes from about 40Mt last year.

S&P Global estimates that Malaysian exports of palm oil could fall by 10% if El Nino is mild and double that if it is severe.

A shortage of palm oils could serve another blow to the already stretched market for edible oils. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, palm oil helped make up for a dearth of sunflower oil, 75% of which is normally produced by the two countries.

In Peru, the water off its coast could get warmer than usual, turning away the species of anchovies that its fishing community relies on, and thus putting a $2 billion a year industry on standstill.

Closer to home, Canadian ranchers are bracing for a long, lean winter after droughts and soaring feed costs.

A CBC article explains that drought’s effects aren’t felt only in summer. For cattle producers, winter can be more severe because the animals’ caloric needs are higher and grazing ground is frozen.

Another problem is that ranchers have now faced back-to-back years of droughts, meaning locally grown livestock feed is in short supply and imported feed costs have skyrocketed. Meanwhile, soil moisture continues to decrease and many water sources are running low.

Over the past several years many producers have had to cull their herds or close ranches, leading to less cattle on Canadian ranches and less beef being produces. According to Farm Credit Canada, via CBC, Canadian beef production in 2023 is down six per cent compared to last year. The supply shortage has driven up cattle prices, which are forecasted to average a whopping 33 per cent higher year-over-year in 2023 and 50 per cent higher than the five-year average.

According to studies, the effects of El Nino tend to peak during December, but the impact typically takes time to spread across the globe. This lagged effect is why forecasters believe 2024 could be the first year that humanity surpasses 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to Professor Adam Scaife, head of long-range prediction at the UK Met Office, who described El Nino as “the biggest single natural variation in climate that we know about on the timescale of a few years.”

Of course, no two El Nino cycles are the same, but the weather impacts on different parts of the world tend to follow a similar pattern.

Generally, the Amazon Basin, Australia, the Indian subcontinent, the Sahel, South-East Asia, southern Africa and northern US states suffer drier conditions, while Central and East Asia, the Horn of Africa, the southern cone of South America and the southern US usually get wetter.

According to the European Central Bank, while an El Nino episode seems to be followed by higher soybean harvests in the United States, it usually has negative effects on US wheat and corn yields. Soybean yields are also reduced in Asia.

The ECB points out that substitution between food commodities complicates price effects, for example during the 1982-83 El Nino, the fish population in Asia and Australia fell, leading to a substitution from fish to soybeans for animal feed.

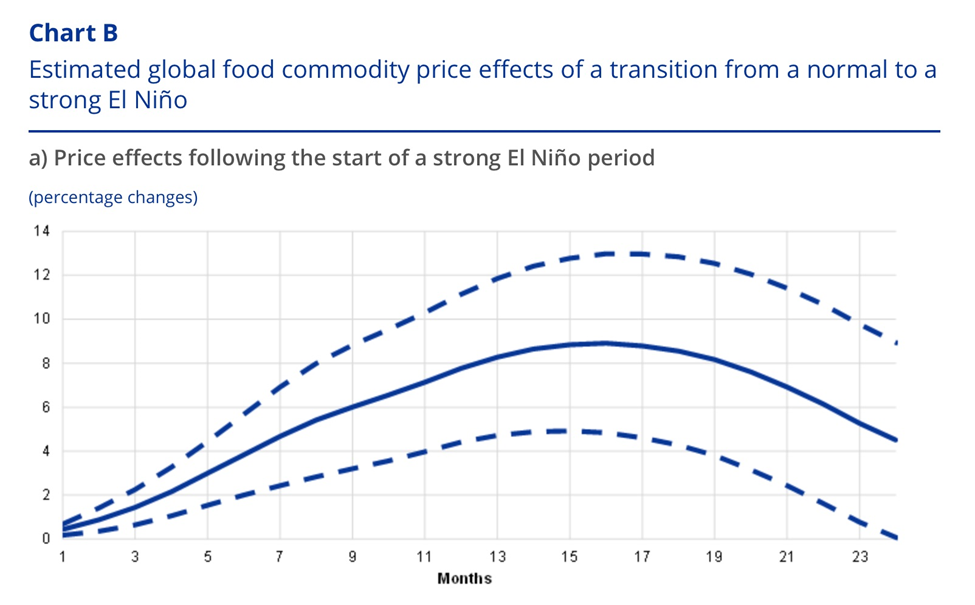

In terms of overall commodity prices, the ECB says the El Niño oscillation accounts for almost 20% of global commodity price inflation movements since 1963 and that a normal El Niño event tends to raise real commodity price inflation by around 3% for 6-12 months after its emergence, with the strongest contribution coming from food commodities…

Global food commodity prices could rise by up to 9% if current El Niño conditions develop into a strong El Niño…

[A] rise in ocean surface temperatures corresponding to the transition from a normal to a strong El Niño would raise global food commodity prices for up to two years, with a 9% peak in price increases occurring 16 months after the start of the strong El Niño episode (Chart B, panel a)…

The upside risks to food commodity prices arising from the development of a strong El Niño phenomenon are particularly pronounced for soybeans, corn and rice, while the expected price effects are upwards but insignificant for wheat and around zero for coffee and cocoa (Chart B, panel b).

Desertification

Broadly speaking, desertification refers to the process of turning arable land into desert usually as a result of deforestation, drought or harmful agricultural practices. Removing vegetation also takes away nutrients from the soil, making the land unsuitable for farming. According to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification UNCCD, around 12 million hectares of productive land become barren every year as a result of desertification and drought.

Warming accelerates desertification because warmer temperatures dry out once-fertile land, which then makes the area even hotter. Removing plants from the ground also increases greenhouse gas emissions, since they can no longer serve as carbon sinks.

A study quoted in The Independent shows that up to 30% of the world’s land surface would become arid if temperatures rise 2° Celsius above pre-industrial levels. We are already at 1.1 degrees.

Desertification is not only bad ecologically, it can also lead to global tensions. Land conflicts in Somalia, dust storms in Asia and food price crises (in Mozambique, Egypt, Serbia and Pakistan) have all been attributed to desertification. The Arab Spring of 2010-11 was sparked by a spike in grain prices a couple of years earlier which meant a 37% rise in the price of bread. Bread in Egypt is called “aish”, or life.

As we strip away the amount of available land for food production, we are literally depriving ourselves of the means to survive. Eventually this will lead to the destruction of human civilization — just as desertification contributed to the collapse of the world’s earliest known empire, the Akkadians of Mesopotamia.

The United Nations has declared soil finite, and predicts catastrophic loss within 60 years. According to the UNCCD, the impact of soil degradation could total $23 trillion in losses of food, ecosystems and income worldwide by 2050.

The world relies on soil for 95% of food production, but the UN (via CNBC) says soil erosion could reduce up to 10% of crop yields by mid-century. This is the equivalent of removing millions of acres of farmland.

Among the countries most affected by soil erosion are Indonesia, India and the Philippines. For a deeper dive into this phenomenon, visit The World Resources Institute.

Water

Parts of the world face constant water stress. There are somewhere between 780 million to one billion people without basic and reliable water supplies. More than 2 billion lack the water requirements for basic sanitation.

It’s also slightly mind-blowing to remember that, while 70% of the earth’s surface is covered by water, less than 1% is potable.

98% of the world’s water is in the oceans — which makes it unfit for drinking or irrigation. Just 2% of the world’s water is fresh, but the vast majority of our fresh water, 1.6%, is in a frozen state, locked up in the polar ice caps and glaciers. Our available fresh water (.396% of total supply) is found underground in aquifers and wells (0.36%) and the rest of our readily available fresh water is in lakes and rivers.

Put another way, only 0.007% of the earth’s water is available for drinking, feeding or fueling (through hydro-electric power or cooling towers needed to run industrial equipment) its 7.5 billion people. We are dancing much closer to the knife edge of water scarcity than we think.

Heat, that is getting worse every year and in some parts of the world is becoming literally unbearable, is inextricably linked to droughts and fresh water loss. Here’s how it works: a lack of precipitation in the mountains from a new or prolonged drought leads to a low snowpack, lessening the annual freshet that fills up rivers, that convey fresh water into lakes and reservoirs.

If this cycle continues year after year, hydro-electric power generation is imperiled, because the reservoirs are too low, as well as nuclear power generation that depends on vast amounts of water to run water-cooled nuclear reactors. This leads to blackouts, when residents and businesses who are running their air-conditioning full tilt to get some relief from the scorching heat, find the grid is overwhelmed. In future, there simply won’t be enough water to supply the amount of electricity required.

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the top three climate impacts on fresh water resources are reduced water supplies, impaired water quality and stressed water infrastructure:

In some parts of the nation, increased demand for water has led to pumping groundwater from aquifers faster than they can be naturally refilled. Persistent droughts in some areas are accelerating this decline. Warming temperatures from climate change may increase the chance of droughts, especially in the West…

Climate change is expected to harm water quality. For example, increased rainfall can lead to more runoff of sediments, nutrients, pathogens, and other substances into water bodies. Increases in nutrient runoff, along with warming water temperatures, can also lead to harmful algal blooms. These algal blooms can kill fish, shellfish, and other animals. They can also make drinking and recreational water sources unsafe for people and pets…

As much of the U.S. water infrastructure nears the end of its planned life, climate change impacts, such as more extreme weather events, will further strain its ability to operate well. Heavy rainfall events can cause dams and levees to fail. In addition, climate impacts on other parts of society may have indirect effects on water utilities. For example, storms that damage power generation or distribution might shut down water and wastewater plants. In other cases, there may be competing needs from surface reservoirs, which face demands as a drinking water supply as well as a source for generating electricity.

In October 2022 Lake Mead, America’s largest manmade reservoir, and a source of water for millions, fell to an unprecedented low. Mead has been shrinking amid a more than 20-year drought in the southwestern United States.

An even more frightening scenario is developing at Lake Powell, a reservoir along the Colorado River that is a quarter of its former size.

While this year brought some welcome relief to both bodies of fresh water — Lake Mead and Lake Powell will both operate at a Tier 1 shortage next year compared to the current Tier 2 shortage — the improvement is only likely to buy users another couple of years.

In 2022 Lake Powell came dangerously close to the dreaded “deadpool”, which is what happens when the lake level falls so low, that not enough water can pass through the dam.

Energy

The pressures on fresh water supply due to droughts and over-use are also affecting the energy sector.

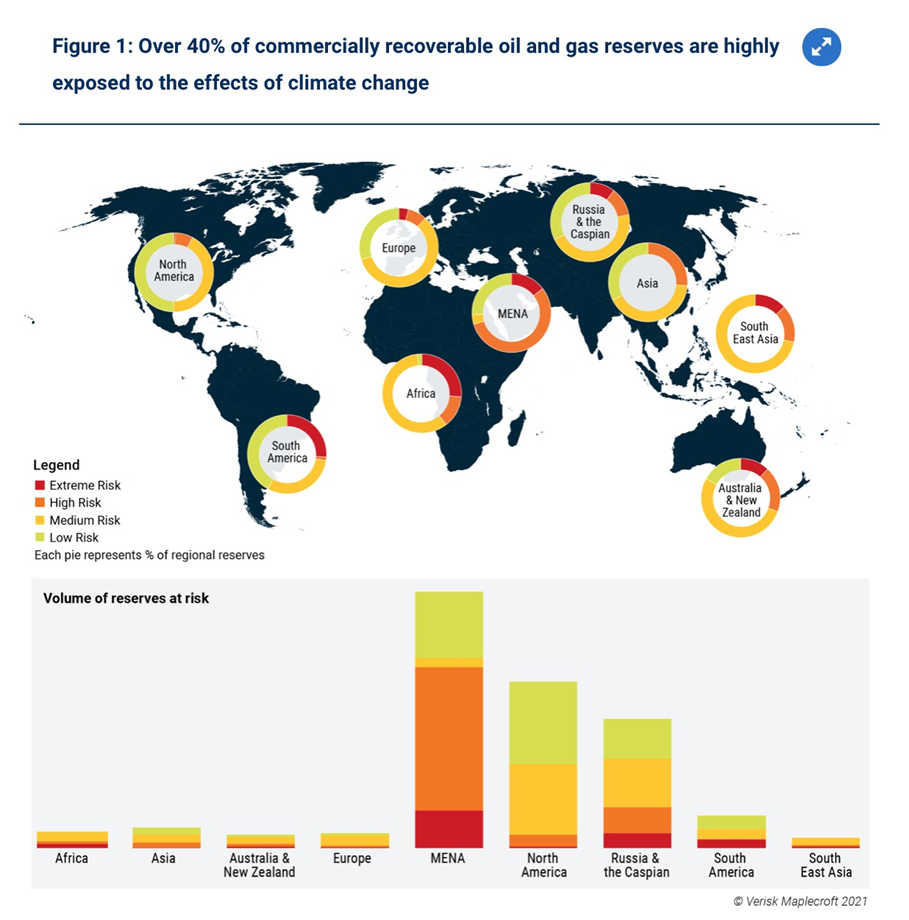

Rising sea levels, record heat, unprecedented extreme weather disasters, and increasingly unstable environmental conditions are making it costlier and more difficult for oil and gas companies to operate, the Center for American Progress stated a few years ago.

Low water levels for example have restricted shipping capabilities, a topic detailed in the section below.

According to a 2021 report by risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft, more than 600 billion barrels of commercially recoverable oil and gas reserves are facing high or extreme risks from more frequent storms and floods, rising sea levels, and temperature extremes. Among the highest-risk producers are Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Nigeria.

Maplecroft noted that climate-related threats to the oil and gas industry have already begun to manifest, giving the example of the 2021 Texas freeze that knocked US oil and gas output to a three-year low. Hurricane Ida caused a record 55 spills in the Gulf of Mexico and disrupted supplies of crude oil and refined products. Record heat in Russia accelerated the thawing of permafrost, damaging buildings and infrastructure in northern regions.

“These types of events are going to become more frequent and more extreme, creating even greater shocks within the industry,” the firm stated.

One problem identified in a 2022 Oilprice.com article is the vast amounts of water required to power green energy operations may not be so easy to find.

Europe’s one-in-500 years drought last year raised concerns by nuclear plant operators that rely on river water to cool their reactors. According to Oilprice, EDF typically uses water from the Rhone and Garonne but rising water temperatures mean that nuclear power output could be reduced during hot periods. The falling water levels have also hindered traditional energy operations such as coal output, according to several European energy firms.

But the issue of water scarcity is perhaps most detrimental to hydropower projects. In the U.S., several hydropower operations are located along rivers with falling water levels, with a higher risk of water scarcity by 2050. Montana, Nevada, Texas, Arizona, California, Arkansas and Oklahoma are the most affected states. A recent study published in the Journal Water found that 61 percent of all global hydropower dams will be in basins with very high or extreme risk for droughts, floods or both. In addition, one in five hydropower dams will be in high flood risk areas, an increase from one in 25 today.

World Wildlife Fund’s Global Freshwater Lead Scientist Jeff Opperman explains, “Hydropower projects must deal with a range of hydrological risks–ranging from too little water to too much–and these risks are projected to increase in many regions due to climate change.” “Already, we’ve seen regions, such as the southwestern US, southern Africa, and Brazil, where hydropower generation has declined due to falling water levels,” he adds.

And it’s not just the U.S. that is facing these challenges. In August, Norway threatened to limit its power exports due to low reservoir levels. The country, which relies on hydropower for around 90 percent of its electricity production, increased regulations on power production to prevent hydroelectric reservoir levels from running out of water.

Shipping

The increased frequency of climate-driven extreme weather events is already taking a huge toll on the world’s shipping routes, and a potentially historical El Nino could make things worse.

Panama, for example, has reduced the number of vessels that pass through its critically important canal due to low water levels caused by severe droughts. Such restrictions create a logjam of ships that are waiting to traverse what’s considered a key global trade route.

The last time a major disruption occurred was in March 2021, when the ‘Ever Given’, one of the world’s largest container ships, blocked the Suez Canal for nearly a week while contending with strong winds, causing calamity throughout Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

Analysts have since warned that extreme weather driven by the climate crisis could increase the frequency of Ever Given-like events, with potentially far-reaching consequences for supply chains, food security and regional economies.

Panama’s announcement came a month after the United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization declared the onset of El Nino, which, according to Xeneta’s chief analyst Peter Sands, could exacerbate the disruptions across the world’s shipping routes.

While the Panama Canal had seen major delays in the past, the impact of global warming today “is perhaps becoming more prevalent” and “more severe”, according to Lars Ostergaard Nielsen, head of the Americas liner operations center at Maersk, the Danish shipping giant.

The severe drought affecting the canal this year due to El Nino means authorities have restricted the number of ships entering the canal to 25 a day. If conditions worsen, the number could go down to 18 on Feb. 1 to conserve water. The Panama Canal Authority normally handles about 36 ships a day, according to Bloomberg.

The publication noted some vessels have waited nearly three weeks to pass through the waterway. The giant bottlenecks at both ends of the canal could even force some shippers to re-route their vessels through the Suez Canal at considerable extra costs.

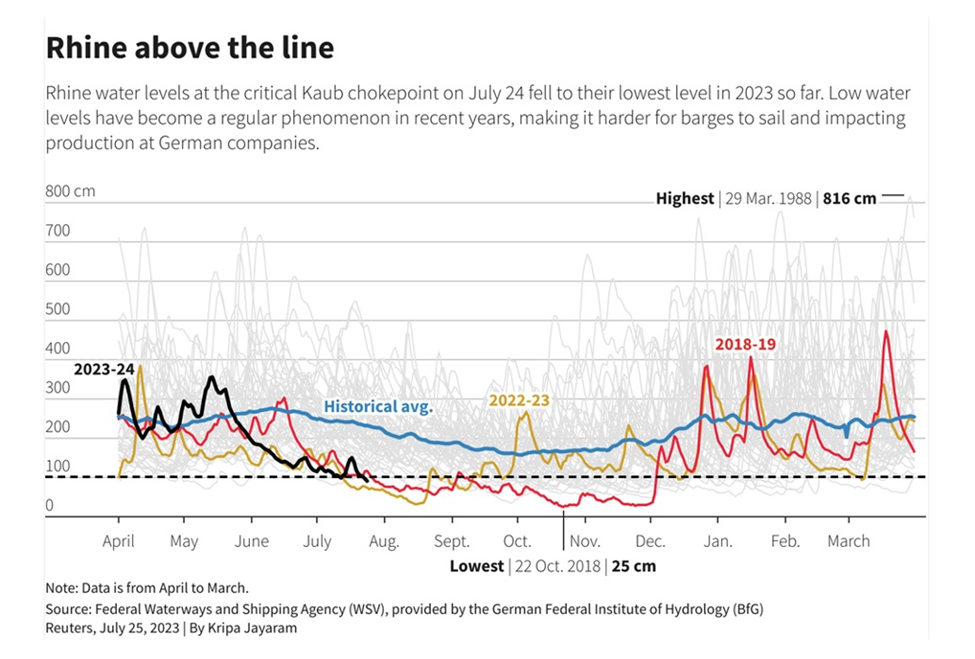

The Panama Canal isn’t the only major waterway struggling to cope with the effects of extreme weather. Falling water levels on Europe’s busiest waterway have become a regular occurrence in recent years, making it more difficult for vessels to transit at capacity.

The Rhine River, which runs through Germany via European cities to the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, is a prime example. In both 2018 and 2022, the Rhine experienced extended periods of low water levels that restricted shipping volumes. Last year’s 182 million metric tonnes of goods transported via Germany’s waterways represented a 6.4% decline from 2021, and the lowest since German reunification.

“The shipping volumes on the river Rhine have been more or less consistent for the past 20 years or so,” Tim Beckhoff, a procurement and supplier management expert at McKinsey, told CNBC. “And, since 2021, we’ve seen them now dropping year over year. It’s a trend, and probably a trend that’s going to continue.”

Metals

Production of non-agricultural commodities could also plummet during an El Nino event. The Economist article noted that in 2015, production at a lithium plant in northern Chile that accounted for 30% of the world’s output was disrupted by heavy rain.

On the other end of the weather spectrum, Chile’s copper production has been dented by a long-running drought in the country’s arid north, where most of the copper mines are.

The largest red-metal producer, accounting for 27% of global supply, recorded a y/y decline of 7% from last November.

“Overall we believe Chile will likely produce less copper from 2023 to 2025,” Goldman Sachs wrote in a note dated Jan 16.

Freshwater supplies are becoming a big problem in Chile. Copper mines there require lots of water to process sulfide ores, and the lower the grade, the more water must be used.

Since major copper miners are increasingly turning to low-grade sulfide deposits to beef up their production, their water consumption is expected to jump up to 20.9 cubic meters per second (about half an average home pool). Water scarcity hinders their ability to produce, and drives mining costs per tonne higher.

Cochilco, the country’s copper commission, estimates the use of desalination by mining to increase 156% through 2030, with 90% of the desalinated seawater used for copper processing.

Of course, it isn’t only Chile facing problems with droughts and heavy rainfall — both of which are capable of interrupting metals extraction.

The first part of 2022 saw the mining industry contend with “a raft of weather-related incidents entirely outside its playbook,” one media source said. Lundin Mining, for example, cut its 2022 copper production forecast after heavy rains reduced output at it Chapada mine in Brazil. Major miners Anglo American and Rio Tinto were also affected. Anglo American reportedly slashed its dividend after torrential rains hurt its iron ore production in Brazil during H1 2022, coal mining in Australia and platinum mining in South Africa.

Rio Tinto’s iron ore shipments fell 2% in the first half of last year partly due to “significantly higher than average rainfall in May” in Australia’s Pilbara region.

Reuters said that severe droughts are drying up rivers and reservoirs vital for production of zero-emission hydropower in several countries.

In some cases, this means governments will have to rely more heavily on fossil fuels, potentially setting back international efforts to fight global warming. As global warming makes already scarce water and mineral resources more difficult and expensive to access, the protection of existing mines and the hunt for new deposits will intensify, resulting in potentially lower production, higher operating costs and conflicts between both water and land users. With much of the world currently experiencing droughts, and signs of warming occurring more frequently and powerfully, it seems to me that ther’es a very real risk to future metals output.

Resource nationalism

The term “resource nationalism” is loosely defined as the tendency of people and governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over natural resources located on their territory. It is often described as a backward form of state protectionism.

A vicious cycle of rising resource nationalism

Chile is perhaps the most significant example of a “resource nationalism” bombshell that was dropped in recent times.

In April 2023, newly elected President Gabriel Boric announced his plan to nationalize the country’s lithium industry, with the state taking a majority stake in all new contracts. According to the media, state-owned copper mining company Codelco will initially sign up partners for new contracts, after which a national lithium company will have that responsibility.

As well, Codelco and another state-owned miner, Enami, will be given exploration and extraction contracts in areas where there are now private projects. The two lithium miners already in Chile, SQM and US-based Albemarle, will continue to operate until their contracts expire.

Chile’s lithium nationalization comes on the heels of a similar plan announced by Mexico, which has yet to even produce the metal but boasts a respectable quantity of lithium reserves (top 10 in the world).

In early 2022, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez, like his fellow leftist in Chile, enacted a sweeping lithium nationalization and later ordered the creation of a new state-run lithium company called LitioMx.

Last year, Indonesia announced an export ban on bauxite, the ore used to make aluminum, that would commence June 2023. The aim is to replicate the success of its 2020 ban on raw nickel exports.

Zimbabwe, which already banned exports of raw lithium ore in December 2022, followed that up with an export ban covering all base mineral ores earlier this year.

Copper appears to be the unwilling posterchild of global warming and resource nationalism combined. On Nov. 28 Reuters reported that reduced supply from Panama and Peru, both major copper producers, could flip the copper market from surplus to deficit in 2024, or at least tighten oversupply if disruptions are not resolved soon.

Exposing the copper surplus myth

On Tuesday Panama’s top court ruled that First Quantum’ contract to operate the Cobre Panama mine is unconstitutional. In Peru, a union representing half of the workers at the Las Bambas copper mine went on strike.

Forget about a copper market surplus. Between those two mines the copper industry has lost 570,000 tonnes of production.

In a recent BMO Metals Brief, head of global commodities research Colin Hamilton wrote that copper prices continue to trend higher due to supply issues following the Panamanian government’s announcement that Cobre Panama would be closed. The government’s renewal of its contract with First Quantum Minerals had reportedly triggered mass protests.

In BMO’s view, though, it is the looming shortage of copper concentrate that is “the more positive fundamental element for the copper market.” As we reported earlier, to ensure self-sufficiency, China is/ has expanded its network of copper smelters, meaning it will start to import much more copper ore for processing domestically. According to CRU, the country is expected to account for about 45% of global refined copper output this year.

China’s new copper smelting capacity is expected to turn China into a net copper exporter by 2025 or ‘26. With so many smelters requiring copper concentrate, the market for concentrate is tightening.

BMO states:

[T]here is little doubt that the current Cobre Panama disruption plus the current Las Bambas strike and downgrades to copper guidance at various key companies will be making concentrate buyers increasingly nervous. Over half of Panama’s concentrate exports, and the vast majority of material from Las Bambas, is shipped to Chinese copper smelters. Spot TCRCs are now at the lowest level since March.

Miners pay smelters a fee to process copper concentrate into refined metal, to offset the cost of the ore. TC/RCs fall when tight concentrate supplies squeeze smelters’ profit margins.

And this just in:

China’s announcement earlier this month that it will tighten export controls on rare earths takes effect on Friday, Dec. 1. The new restrictions will run until the end of October, 2025. The country has also imposed export curbs on gallium and germanium, used in semiconductors, and graphite, used in the anodes of lithium-ion batteries. Starting Dec. 1, companies that want to export certain graphite products will be required to apply for a permit from Chinese authorities.

Conclusion

I’ve been right in my prediction that the Fed would pause in June, and hike once or twice more before the end of the year.

I’ve also voiced my opinion that we get a soft landing with no, or an extremely shallow and very short recession, with the important proviso that the Fed pauses its rate-hiking cycle, which it has already done. For the Fed this means the inflation rate is coming down. Remarkably, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates fast enough, and quick enough, to reverse the inflation rate, without causing a severe downturn. And it’s done it in an extremely short amount of time.

Companies making money hand over fist are fueling the job market. Unemployment, a key Fed metric, is currently at 3.9%, nationally, lower than the long-term average of 5.7%.

We already know corporations borrowed low and channeled a lot of profits into money-market funds bearing high interest rates. That helped stocks immensely. Now we have a huge increase in reserves and liquidity.

And remember all that cash, estimated to be over $6 trillion, will be withdrawn from these money market funds, now earning 5%, when interest rates start to go down, which they already have.

When the Federal Reserve starts to cut interest rates, anticipated sometime in early 2024, we will start heading towards a much more commodities-friendly real interest rate environment (as I write copper is up US$0.010 and gold has hit another all-time record).

Remember, the Fed never wanted to raise interest rates, it took a long time to start tightening but once it did, it moved very quickly, acting on the advice that if they jacked interest rates up fast over a short period of time they would have a better chance of avoiding a recession.

So, when are they going to start lowering rates? One of the most hawkish, if not the biggest hawk on rate hikes, Fed Governor Roger Altman, has turned dovish, saying the Fed’s plan is working so well they might have to start lowering rates in March 2024.

And as Zero Hedge recently observed, if rates keep rising “higher for longer”, the current weighted average for total outstanding debt will go from 2.76% to 4% in one year:

That would be a complete disaster for the US, interest payments on total US debt of $32.3 trillion would hit $1.3 trillion within 12 months, potentially making interest on the debt the single biggest US government expenditure surpassing the military and social security! That won’t look good on your resume.

Of course, 2024 is an election year and the president’s and vice-president’s positions are up for grabs. All 435 seats in the US House of Representatives and 34 of the 100 sets in the Senate will be contested.

Lately Biden has started to attack Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, over the GOP’s two weaknesses: abortion, and now another hot issue, and another loser issue for the GOP, Obamacare, aka the Affordable Care Act. 40 million Americans are receiving coverage under the ACA, do you think they could swing the election? Why not leave the ACA in 2018?

Donald Trump’s popularity, the whole time he was President, never rose above 50%. Three weeks after January 6th his rating had sunk to 28%. President Biden’s popularity is at an all time low @ 40%. Its not down there because of immigration or the economy. It’s there because a younger generation of Democrats sits in harsh judgement of his handling of the Israel/ Hamas war.

When it comes down to a vote between Trump and Biden, when it comes down to a vote for the Presidency of the US, and control of Congress there is no doubt in my mind that Biden and the democrats will win, maybe by an overwhelming majority.

What that means for commodities is a continuation of the Democrat’s spending policy, Moderm Monetary Theory (MMT) – Debt doesn’t matter as long as interest rates are low. The debt can gets kicked down the road.

Infrastructure spending will soar, doesn’t matter if its blacktop, green or high-tech, literally trillions of dollars will be spent on a wave of US and global projects.

It means huge demand for infrastructure metals like iron ore, copper, zinc and nickel. Many metals — including copper, graphite, nickel and cobalt — are going to be increasingly hard to source in the West due to lack of exploration spending, a lack of refineries and smelters and 20 year permitting timelines to build new mines.

Throw in the looming threats of global warming, El Nino, and resource nationalism which will only drive prices higher.

Think about it: we can’t mine, we can’t refine, we’re running out of fresh water, our oceans are dying, and people are scrambling to either stop resource development or governments are hanging on tightly to whatever resources they have, and charging higher resource rents for it.

The end result is a perfect storm for commodities — a major bull market across the board. The shift from tight to loose monetary policy has yet to happen, but it’s coming.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.