How China cornered the market for critical minerals and can the West break it’s near monopoly on these metals? – Richard Mills

2023.11.26

China is already gobbling up copper and copper ore at an incredible rate, and now they want even more. I have no doubt China is deliberately tightening their grip on the global copper market like they have already accomplished in the lithium, cobalt, graphite, nickel, steel and rare earths supply chains.

“In its critical minerals strategy in December, Canada listed copper as one of the top six critical minerals, along with lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt and rare earth elements, due to its importance in the clean technology sector,” states the Financial Post.

It appears the West has been snookered again.

Strategies and lists

Is it a coincidence that the six metals Canada has listed as strategically important, are the same metals that China has a lock on? We think not.

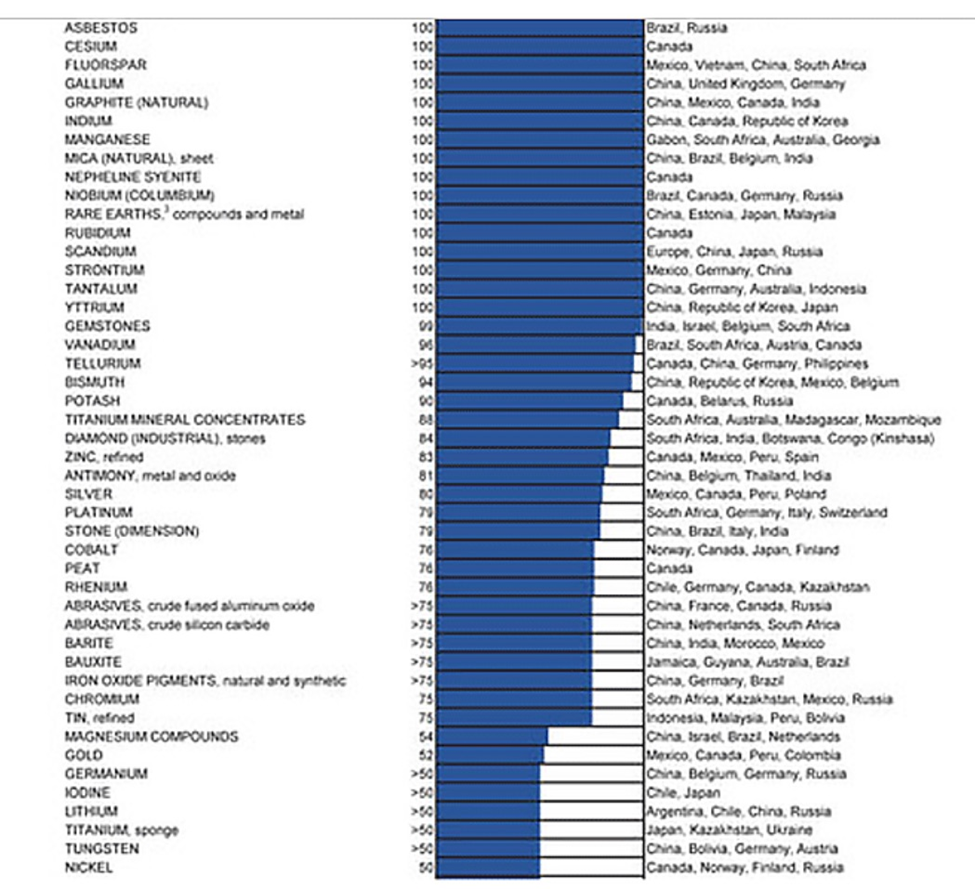

In 2021, Canada announced the release of the country’s critical mineral list, consisting of 31 minerals/metals . The country was a Johnny-come-lately to lists previously published by the United States, the EU, Japan and South Korea, as summarized in the table below.

A blog piece notes there are nine minerals that appear on all lists: antimony, cobalt, gallium, indium, lithium, niobium, platinum group elements, tungsten and vanadium.

In 2022 Ottawa unveiled its Critical Minerals Strategy, earmarking nearly CAD$3.8 billion over eight years to develop Canada’s critical minerals industry, through technologies like batteries, wind turbines and solar panels.

Out of the above-cited list of 31 critical minerals, the strategy prioritized six: lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt, copper, and rare earth elements.

Projects involving these six minerals will be backed by a CAD$1.5 billion Critical Minerals Infrastructure Fund announced by the federal government this week

Included on the US Geological Survey’s list of 35 critical minerals are the building blocks of the new electrified economy, including lithium and graphite. China has a stranglehold on processing both metals, meaning it can weaponize them during conflicts with its adversaries, as it has done before with Japan (rare earths), and the United States (gallium, germanium, graphite).

According to data collected by the UGS, the United States is reliant on totalitarian regimes with dictators installed for life for 32 of 47 minerals — an eye-watering 70%! We are of course talking about China (23) and Russia (9).

The 2022 critical minerals list below, with a brief description of each, expands upon the 2018 list that detailed 35 mineral commodities considered critical to the economic and national security of the United States.

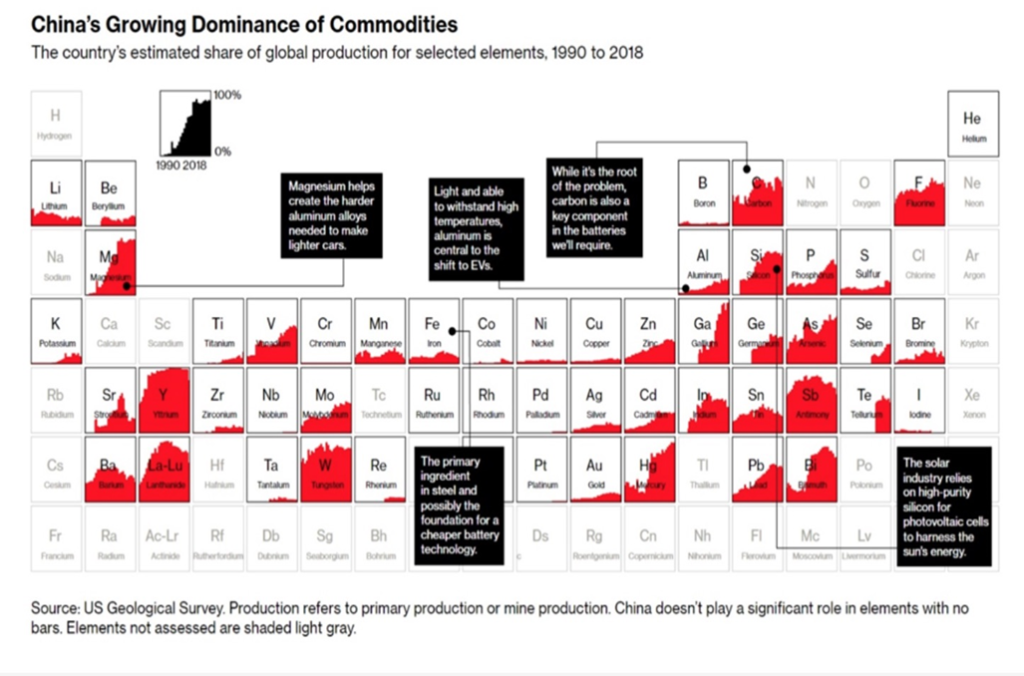

China’s dominance

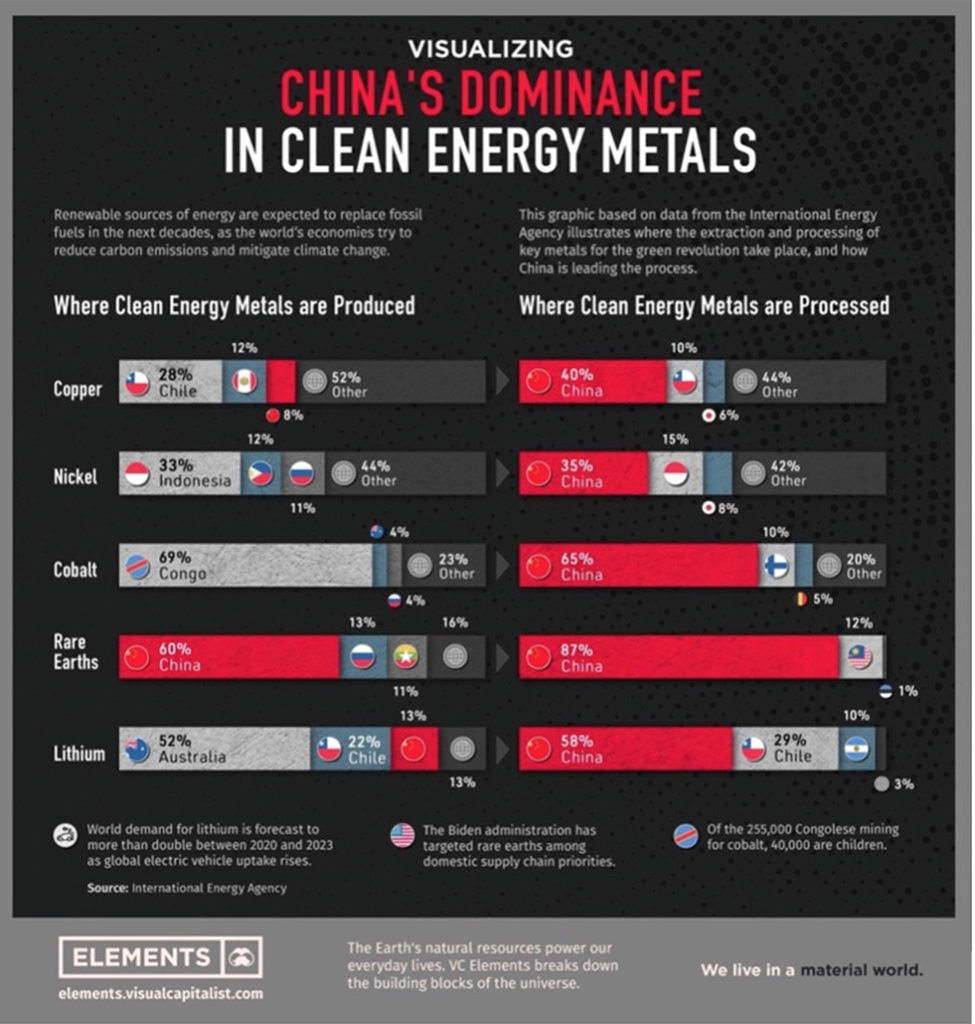

Indeed, when it comes to raw materials for the electric vehicle industry, China is undisputedly the most dominant force on the planet.

For decades, China has dominated critical minerals, with Canada and the US, among other nations, all too willing to let Beijing do the mining and/ or processing and sell the end-products, such as rare earth magnets, lithium batteries and battery grade graphite, back to us.

Almost every metal used in EV batteries today comes from there, either mined or processed. Thanks to its technological prowess in refining, China has established itself as the across-the-board leader in the battery metals processing business (see below).

China’s modus operandi is to build mines and provide infrastructure that supports, and gains the favor of, the local population, such as schools, health clinics, roads and clean water systems. Usually in exchange for offtake agreements.

A good example is what happened in Argentina.

In 2020 Argentina defaulted on the bonds it sold to Wall Street, and it still owes tens of billions of dollars to the IMF. “Argentina’s economy is so calamitous that only adventurers like China can do business here,” Bloomberg quotes the man who ran the provincial energy and mining company, Jemse.

The province of Jujuy is home to an Australian-Japanese venture that became Argentina’s second lithium producer in 2015. Minera Exar, majority-owned by giant Chinese battery company Ganfeng Lithium, has become the third (Lithium Americas’ Cauchari-Olaroz brine lithium project), starting production earlier this year.

Chinese money and technology also helped build one of Latin America’s largest solar plants in Jujuy.

Deals are made between governments, usually with a China state-owned enterprise becoming the mine owner and operator. The end goal is to purchase the raw ore from mines in countries China likes doing business with, and then build refineries at home to process the metals into more expensive end-products.

Indeed, Beijing has been very smart about courting developing countries by offering them financial support in exchange for access to minerals and regional influence. Excluding Mexico, which has a free-trade agreement with the United States and Canada, China is now Latin America’s largest trading partner, according to UN trade data from 2015-21. Consider this alarming statistic: in 2000 China’s trade with Latin America amounted to just $12 billion, but by 2019 it had grown 27.5X to $330 billion. By 2035 trade between China and Latin America/ the Caribbean, is expected to double again, to $700 billion.

According to the International Energy Agency, the country accounted for roughly 60% of the world’s lithium chemical supply in 2022, as well as producing three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries.

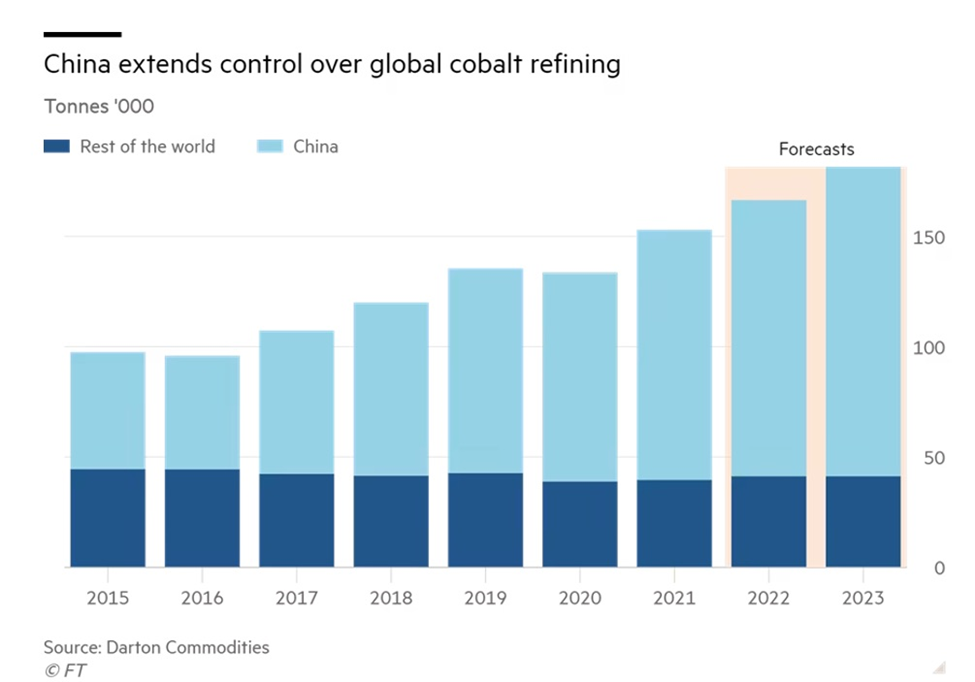

It also has a tight grip over the world’s supply of cobalt through its mining operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Over the next two years, China’s share of cobalt production is expected to reach half of global output, up from 44% at present, according to UK-based cobalt trader Darton Commodities.

The IEA estimates China’s share of refining is around 50-70% for lithium and cobalt, 35% for nickel, and 95% for manganese, despite being directly involved in a small fraction of the mine production.

The nation is also responsible for nearly 90% of rare earth elements, which are essential raw materials for permanent magnets used in wind turbines and EV motors, as well as 100% of graphite, the anode material in EV batteries.

Rare earths

China mines about 80% of the 17 elements that appear on the Periodic Table and has a lock on ~90% of rare earth processing.

It’s a little-known fact that the United States was once the largest producer of rare earths in the world, at the Mountain Pass Mine in California.

Little happened at Mountain Pass during the 1950s except for the odd bit of research by the defense and scientific communities, but that all changed in the 1960s with the color TV. The discovery of europium, which emits a brilliant red light when bombarded with electrons, ushered in the age of technicolor, and Mountain Pass, which had abundant europium, flourished. Rare earths mined there were also used in medical scanners, lasers, fluorescent lights and microchips.

In 1980, a misclassification of rare earths had catastrophic consequences for US rare earth mining. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the International Regulatory Agency placed rare earth mining under the same regulations as mining thorium — a radioactive element that drops out when processing heavy rare earth minerals like monazite.

New, onerous regulations on thorium made the mining and refining of thorium-bearing rare earth elements risky. Over the next two decades, the US rare earth mining industry collapsed.

The Chinese filled the void left by US rare earth mining with gusto. They

began mining the massive Bayan Obo mines north of Baotou, Inner Mongolia — containing an estimated 70% of the world’s rare earths reserves. A flood of Chinese rare earth oxides into the market hurt Molycorp, which shut down its processing facility in 1998. Processing plants in the US owned by German and Japanese firms moved their operations to China.

China wouldn’t have been able to develop its REE industry if it wasn’t for the dubious acquisition of Magnequench, a division of General Motors established in 1986.

In 1988 Indianapolis-based Magnequench was mysteriously sold to members of former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s family. The facility was then shut down and moved to China in 2000.

(For the fascinating story of how Magnequench and its technology was ceded to the Chinese, read a 2006 article by Jeffrey St. Clair.)

How the US lost the plot on rare earths

Since then, rare earth metals, alloys and magnets needed by US defense contractors come either directly or indirectly from mostly China. According to the US Geological Survey, the United States relies on Chinese imports for at least 20 minerals, including rare earths.

The final nail in the coffin for US rare earths came in 1998, when the US National Defense Stockpile sold the entire strategic reserve of rare earths.

In 2009 the Chinese government-imposed export controls on its rare earths, meaning a 40% drop in exports.

A year later, an international incident sent rare earth oxide prices into the stratosphere. In September 2010 a Japanese naval vessel interdicted a Chinese fishing boat near the Senkaku Islands, which Japan and China both claim ownership of, and detained the captain. The response hardly seems balanced in retrospect, but the Chinese decided to ban all rare earth exports to Japan, then an industrial powerhouse and China’s largest REE customer. The rare earths market panicked, and within months, all of the rare earth oxides gained in price.

While the spike in rare earths prices was good for miners like Molycorp and the numerous exploration companies that sprang up in search for them, buyers of products made from rare earths balked and pressured governments to do something about it. The US, European Union and Japan brought a case to the World Trade Organization to try and settle the dispute and get China to lift the restrictions.

In 2015 it did, resulting in a torrent of Chinese rare earth exports into the market and the inevitable collapse in prices. The move caught Molycorp off-guard. The company had just spent over a billion dollars on another upgrade at Mountain Pass but within months, the company fell deeply in debt and went bankrupt.

The mine was put on care and maintenance and eventually sold at auction in the summer of 2017 for a shocking $20.5 million – a fraction of its previous worth. The new owner was MP Mine Operations LLC, an American-led consortium, with Chinese rare earths miner Leshan Shenghe Rare Earth Co. holding a minority interest. Mountain Pass currently ships rare earths concentrate for refining in China — although the company says it is investing $700 million to restore the mine’s processing capabilities, focusing on the magnet elements dysprosium and terbium.

Lithium

Lithium and graphite are essential for the lithium-ion batteries that go into electric vehicles.

These batteries consist of an anode, cathode, separator, electrolyte and two current collectors (positive and negative). The cathode contains lithium, either in the form of lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide, while the anode is made up of graphite.

The global lithium-ion battery industry is expected to grow at a CAGR of 16.4% from 2020 to 2025, reaching USD$94.4 billion by 2025 from $44.2 billion in 2020. Growth will be driven not only by the need for plug-in electric vehicles and hybrids, but grid storage applications for which the dominant technology is lithium-ion.

Demand for lithium carbonate is expected to rise at a compound annual growth rate of 10-14% until 2027, while lithium hydroxide demand is seen climbing at a 25-29% CAGR.

A recent study by BloombergNEF shows that 5.3 times more lithium will be demanded by 2030 compared to current levels.

We know from previous articles that China has been extremely active in acquiring ownership or part-ownership of foreign lithium mines and inking offtake agreements.

The stand-out example is Greenbushes in Australia. The continent’s largest hard-rock lithium mine is 51% owned by a partnership between ASX-listed IGO and China’s Tianqi Ltihium. The remaining share is owned by US chemicals giant Albemarle.

In 2017 Chinese private equity firm GSR Capital bought Nissan’s electric vehicle battery business and then Chinese carmaker Great Wall Motor signed an agreement with Pilbara Minerals, the Australian lithium miner, to secure supplies for the next five years, the Financial Times reported.

The following year, China’s Tianqi Lithium purchased a 23.7% stake in Chilean state lithium miner SQM, despite concerns from regulators that the $4 billion tie-up would give Tianqi a near monopoly over the lithium market and unprecedented pricing power.

Australia’s AVZ Minerals in 2021 secured an offtake agreement with privately held Yibin Tianyi Lithium Industry for the supply of spodumene concentrate (SC6) from the Manono lithium and tin project in the DRC. Yibin Tianyi will purchase up to 200,000 tonnes per annum of SC6 for an initial three-year term following commencement of production with an option to extend for an additional two years.

China produces roughly two-thirds of the world’s lithium-ion batteries and controls most of its processing facilities.

The US only produces 1% of global lithium supply and 7% of refined lithium chemicals, versus China’s 51%. America is about 70% dependent on imported lithium.

According to S&P Global, via The Assay, since 2018, China has been the catalyst behind all major lithium M&A deals over $100 million.

Chinese firms bought 10 of the 20 lithium mines available, for an estimated US$7.9B, while Australian companies came a distant second, obtaining just five mines over the past five years.

Half of those mines are in Canada and Australia, with the others in Argentina, the DRC and Zimbabwe. While Australia produced 47% of global lithium supplies in 2022, it exported 90% of its output to be refined in China.

Between 2018 and 2020, China invested $16 billion in overseas mining, including in South America’s “lithium triangle” of Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, which accounts for about half of the world’s lithium resources.

As of 2022, Tianqi Lithium was the second largest shareholder in SQM, the leading brine-based lithium producer, @ 25.9%.

Finally, Reuters said Chinese companies have spent more than $1 billion acquiring and developing lithium projects in Zimbabwe. This includes:

- Huayou Cobalt opening a $300 million lithium processing plant at its Arcadia mine, which it purchased the previous year from Prospect Resources for AUD$422M.

- Chengxin Lithium Group commissioning a lithium concentrator to produce 300,000 tonnes per year at the Sabi Star mine in eastern Zimbabwe.

- Sinomine Resource Group completing a $300M lithium plant, after it bought Bikita Minerals, one of Africa’s oldest lithium mines, for $180M.

Graphite

An average plug-in EV has up to 70 kg of graphite.

Due to its natural strength and stiffness, graphite is an excellent conductor of heat and electricity. It is also stable over a wide range of temperatures.

Hence, graphite is considered indispensable to the global shift towards electric vehicles. It is also the largest component in batteries by weight, constituting 45% or more of the cell. There is nearly four times more graphite feedstock consumed in each lithium-ion cell than lithium and nine times more than cobalt.

Graphite is included on a list of 23 critical metals the US Geological Survey has deemed critical to economy and national security.

According to the USGS, the battery end-use market for graphite has grown by 250% globally since 2018.

Moreover, graphite requires the largest production increase of any battery mineral to meet forecast demand.

It’s thought that battery demand could gobble up well over 1.6 million tonnes of flake graphite per year (out of 2022 mine supply of 1.3Mt).

But the mining industry still needs to supply other graphite end users. Currently the automotive and steel industries are the largest consumers of graphite, with demand across both rising at 5% per annum.

The US could be left in the dust as it continues to play catch-up in the EV race. China dominates global supply of both synthetic and natural graphite, accounting for around two-thirds of natural graphite production and supplying around 98% of the world’s synthetic graphite anodes, according to consultancy Benchmark Minerals.

Graphite is a key vulnerability in the US-China “electrification war” – Richard Mills

A return to $100 oil would make synthetic graphite more expensive than natural/ mined graphite, prompting a switch to the latter.

Some of the world’s largest auto and battery makers aren’t waiting until that happens. They, and the US government, are racing to secure graphite supplies ahead of a coming supply shortage.

According to BMI, via the Wall Street Journal, by 2030 demand for natural graphite is projected to outstrip supply by about 1.2 million tonnes.

But remember, China mines 66% of the world’s graphite. The country also makes nearly 100% of graphite anode material.

The fact that the US currently has no domestic graphite production means that graphite means it has become part of the escalating conflict between the United States and China regarding critical minerals.

When China announced restrictions on exports of gallium and germanium in July, a top Chinese official said it was “just the start” if the West continued to target its high-technology sector. In October Beijing made good on that promise, prohibiting exports without a license of high-purity synthetic natural flake graphite, including spherical and expanded forms, Reuters said.

Cobalt

Cobalt is one of the common denominators between the two main types of EV batteries, nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM). These metal combinations are the preferred cathode materials, which range from 5% to 30% cobalt, depending on the performance, energy density, charge time, charge life, safety, and cost of the battery. A typical smart phone battery contains 5 to 20 grams of cobalt, compared to an EV battery which requires between 4 and 30 kg.

Two-thirds of cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and over half of the brittle, silvery-grey metal is refined in China. Very small amounts are mined in North America as by-products.

China has a tight grip over the world’s supply of cobalt through its mining operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Over the next two years, China’s share of cobalt production is expected to reach half of global output, up from 44% at present, according to UK-based cobalt trader Darton Commodities.

Cobalt could easily be targeted by China for export restrictions or an embargo (same as gallium, germanium and graphite), which would likely harm US end-users that depend on a reliable cobalt supply chain.

According to the USGS, in 2022 the United States only mined 800 tonnes of cobalt, while Canada produced 3,900 tonnes. Compare this to the DRC’s production of 130,000 tonnes.

In a $9 billion joint venture with the DRC government, China got the rights to the vast copper and cobalt resources of the North Kivu in exchange for providing $6 billion worth of infrastructure including roads, dams, hospitals, schools and railway links. China controls about 85% of global cobalt supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest producer of the mineral, to sell cobalt hydroxide to Chinese chemicals firm GEM. China Molybdenum is the largest shareholder in the major DRC copper-cobalt mine Tenke Fungurume, which supplies cobalt to the Kokkola refinery in Finland. China imports 98% of its cobalt from the DRC and produces around half of the world’s refined cobalt.

Nickel

Nickel is used in two of the dominant battery chemistries for EVs, the nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) battery used in the Chevy Bolt (also the Nissan Leaf and BMW i3) and the nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) battery manufactured by Panasonic/Tesla.

Battery manufacturers have been developing nickel rich NCM 811 batteries (80% nickel, 10% cobalt and 10% manganese) because they have longer lifespans and allows electric vehicles to go further on a single charge.

China’s most recent foray into overseas minerals acquisition involves Indonesian nickel. The country is using Indonesia’s ban on raw nickel exports to monopolize the nickel market.

Could an emboldened China reveal the West’s dependence on the minerals it controls?

Tsingshan, the world’s largest stainless-steel maker, plans to construct an Indonesian plant to produce nickel-cobalt salts from nickel laterite ores. Using previously uneconomic high pressure acid leaching (HPAL) technology Tsingshan says it will transform class 2 laterite deposits into class 1 metal for the electric vehicle battery market.

In April 2021, Chinese battery maker CNGR announced it will buy nickel matte, used to make EV battery chemicals, from Tsingshan’s $243 million smelting project on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

A month later, China’s Lygend Mining and its $1 billion nickel and cobalt smelting operation became the first project in the southeast Asian country to reach full production.

In Indonesia, nickel is produced from laterite ores using the environmentally damaging HPAL technique. (HPAL stands for High Pressure Acid Leach). The advantage of HPAL is its ability to process low-grade nickel laterite ores, to recover nickel and cobalt. However, HPAL employs sulfuric acid, and it comes with the cost, environmental impact, and hassle of disposing the magnesium sulfate effluent waste.

The Indonesian government banned the practice of dumping tailings into the ocean (DST) for new smelting operations, but it isn’t yet a permanent ban.

Most of four HPAL plants currently under construction, led by Chinese stainless-steel producers and battery makers, plan to continue the environmentally egregious practice of DST, due to the much higher cost of managing the tailings on land.

Not only that, the process of refining nickel to make nickel pig iron, and now, nickel matte, is highly energy-intensive (it relies on coal-fired power) and creates a lot of air pollution.

Chinese metals companies benefit from long-standing relationships with Indonesia. “When Chinese companies are developing assets in Indonesia, there’s a very steady stream of parts and labor and material going from China to Indonesia to enable them to build new assets quickly, on schedule, and on budget,” said Harry Fisher, a project manager at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

This efficiency has helped Chinese nickel producers quickly pivot from focusing on nickel pig iron, used for stainless steel, to mixed hydroxide precipitate, or MHP. The vibrant green powder is quickly becoming a preferred feedstock for batteries.

MHP contains both very high-purity nickel and a small quantity of cobalt. Thanks to MHP, Benchmark predicts that by 2030, Indonesia will produce 80,000 tons of cobalt—roughly 20 percent of global production.

Indonesia now has three plants capable of producing 164,000 metric tons of MHP yearly. Some 26 more have been proposed. All — bar three scheduled to open 2026 — involve Chinese companies.

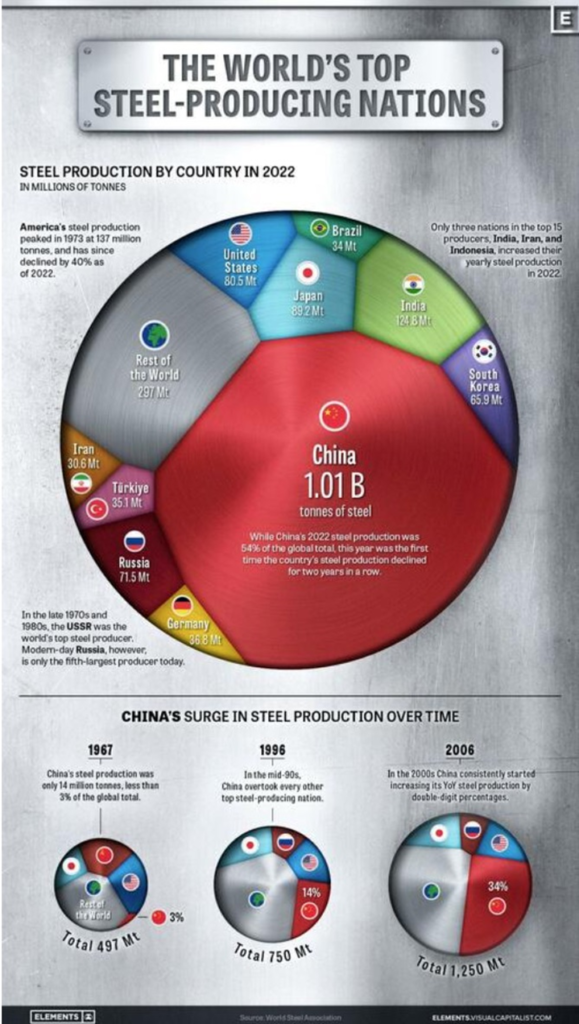

Steel

In 2007 when nickel prices ran past $50,000 a tonne, top stainless steel consumer China balked. Beijing discovered an alternative to pure nickel in the making of stainless steel, called nickel pig iron (NPI). The emergence of NPI revolutionized the nickel industry. The bulk of production shifted from the northern latitudes that host nickel sulfide deposits, to huge nickel laterite belts found around the equator — mostly in the Philippines and Indonesia.

China currently makes up more than half of the world’s steel production.

However, this wasn’t always the case. As Visual Capitalist notes in a recent article,

In 1967, the World Steel Association’s first recorded year of steel production figures, China only produced an estimated 14 million tonnes, making up barely 3% of global output. At that time, the U.S. and the USSR were competing as the world’s top steel producers at 115 and 102 million tonnes respectively, followed by Japan at 62 million tonnes.

Almost three decades later in 1996, China had successively overtaken Russia, the U.S., and Japan to become the top steel-producing nation with 101 million tonnes of steel produced that year.

The early 2000s marked a period of rapid growth for China, with consistent double-digit percentage increases in steel production each year.

What accounts for China’s success in steelmaking? According to Forbes, the Chinese since the mid-2010s have been flooding the global market with steel that is 20 to 50% cheaper than its competitors. Cheap Chinese steel led to the US-China trade war in 2016, which imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum shipped from China and other countries. India and Britain also imposed steel tariffs on China.

In 2016, Forbes wrote, There are now thousands of steel mills in China, and it’s not easy to shut them down immediately just because of slowing demand and higher tariffs in the developed world. Plus, local governments simply don’t want to shut them down and have a bunch of unemployed steel workers on their hands. The latest five-year plan stated that the government wants to help with this by setting a goal of moving half a million people out of sectors like steelmaking, but this process is going to be painful.

Two years later, Wolf Street noted that among the 12 largest steelmakers in 2017, five were owned by Chinese government entities. They include the world’s second largest steel company, China Baowu Steel Group, number four Hesteel Group, Ansteel Group (#7), Shougang Group (#9), and Shandong Steel (#12).

Copper

In February CNBC reported that “a copper deficit is set to inundate global markets throughout 2023, fueled by increasingly challenged South American supply streams and higher demand pressures.”

Wood Mackenzie is forecasting major deficits in copper to 2030, attributed largely to unrest in Peru and higher demand for copper in the energy transition industry.

Exposing the copper surplus myth

The mining industry’s experience of China locking up the world’s mineral resources testifies to how far the Chinese will go to ensure their ever-growing demand for mined commodities is met.

Two large Peruvian copper mines are owned by Chinese companies. Chinese state-run Chinalco owns the Toromocho copper mine, while the La Bambas mine is a joint venture between operator MMG (62.5%), a subsidiary of Guoxin International Investment Co. Ltd (22.5%) and CITIC Metal Co. Ltd (15%). The Chinese-backed Mirador mine in Ecuador opened in 2019.

New copper supply is concentrated in just five mines — Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC.

Four out of five of these mines either have offtake agreements in place with non-Western countries (South Korea and China), or the mines are partially owned by Japanese companies that have a say in where some of the mined copper is destined. (i.e., Japan)

China long ago put a lock on much of Africa’s vast resources.

At Ivanhoe Mines’ massive Kamoa-Kaukula copper mine, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project.

Earlier this year, Zijin Mining acquired a 50.1% stake in Tibet Julong Copper for $548 million. The most recent copper deal saw China’s MMG agreeing to pay $1.9 billion for Cuprous Capital, a private company that owns the Khoemacau operation in Botswana.

Last week Bloomberg reported that Antofagasta, a Chilean miner, and Jinchuan Group, a Chinese smelter, agreed to set 2024 treatment and refining charges 9% lower than this year, “as the supply of mined ore tightens and refining capacity expands.”

The charges, of $80 per ton and 8 cents per pound, compare to a six-year high of $88/t and 8.8 cents/lb in 2023, and are the first decline in fees in three years.

Readers of last week’s AOTH article will recall that to ensure self-sufficiency, China is/ has expanded its network of copper smelters, meaning it will start to import much more copper ore for processing domestically.

“Like all countries, China sees a strategic need for copper — particularly now with the growth in green energy applications — and China like other countries wants to ensure self sufficiency,” said Craig Lang, principal analyst at researcher CRU Group.

“China will account for about 45% of global refined copper output this year, according to CRU,” states Bloomberg.

China’s new copper smelting capacity is expected to turn China into a net copper exporter by 2025 or ‘26. With so many smelters requiring copper concentrate, the market for concentrate is tightening.

Shedding reliance

In a February 2022 fact sheet, the White House conceded that: “The US is increasingly dependent on foreign sources for many of the processed versions of these minerals. Globally, China controls most of the market for processing and refining cobalt, lithium, rare earths, and other critical minerals.”

Speaking to CNBC, Special Presidential Coordinator Amos Hochstein called this “a major concern for the US” and for the rest of the world.

“We can’t have a supply chain that is concentrated in any country, doesn’t matter which country that is,” he said. “We have to make sure from the mining and refining process to the building of the batteries and wind turbines that we have a diversified system that we can be well supplied for.”

One positive development is the Inflation Reduction Act, a landmark piece of climate legislation enacted by the US Congress to jumpstart clean energy production.

The IRA represents the single largest investment in climate and energy in American history. The act, which aims to cut 2005 emissions levels in half by 2030, would provide US consumers tax credits of up to $7,500 per electric vehicle, provided the parts and materials are sourced from countries with which Washington has a free trade agreement. This includes Canada and Mexico.

Another recent trend is “friend-shoring”. The idea is for a group of countries with shared values, and at a similar stage of development, to source raw materials and to manufacture goods. The goal is to prevent less like-minded nations from exploiting their comparative advantage, or in some cases, their monopolies, in key raw materials, technologies or products.

First mentioned publicly by Janet Yellen, the US Treasury Secretary, in 2020, the target is clearly China and Russia. The US wants to reduce dependence on authoritarian regimes like China that supply most the world’s rare earths and magnets and dominate the production of several battery/ electrification metals including copper, zinc, tin, lithium and graphite; and diversify away from Russian suppliers of critical commodities such as energy, food and fertilizer. In some cases, like semiconductors, the goal is to divvy up supply between friendly nations. For example the US has begun engaging with South Korea to diversify chip production away from Taiwan, which is its no. 1 supplier but faces a security threat from China.

An example of friend-shoring put into practice is the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), formed as a sort of “metallic NATO”. Members include the United States, Canada, Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the European Commission.

Theoretically open to all countries that are committed to “responsible critical mineral supply chains to support economic prosperity and climate objectives,” the MSP aims to help “catalyze investment from governments and the private sector for strategic opportunities … that adhere to the highest environmental, social, and governance standards,” reads a statement from the US State Department.

(Curiously, when the MSP was first convened in September 2022, additional countries in attendance included Argentina, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mongolia, Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania, and Zambia.)

The DRC? The Congo’s staggering economic potential — it contains 5% of the world’s copper and 50% of its cobalt — is matched only by its poverty and corrupt mismanagement.

Tariffs

US-China relations have been strained over the past several years. Former President Trump started a trade war with America’s largest trading partner, imposing billions worth of tariffs on Chinese imports and accusing Beijing of engaging in longstanding unfair trade practices as well as intellectual property theft.

President Biden has not canceled the Trump tariffs; in fact, he increased them. CNBC reported that tariffs on select Chinese goods were imposed in three stages between 2018 and 2022. Currently, two-thirds of US imports from China are under tariff, with the average set at 19.3%, more than six times higher than before the trade war began. Chinese tariffs cover 58% of US exports at an average 21.1%.

In October the Biden administration announced plans to halt shipments to China of chips designed by Nvidia and others, to try and stop Beijing from using advanced US technologies to strengthen its military.

Western governments think they can pour billions of dollars into subsidizing EV battery plants, not understanding how the raw materials are acquired and who controls them. In fact, when it comes to security of supply, we are no better off than before; we’re just assembling battery parts that were made elsewhere.

Infrastructure snafu

A good example of how America is shooting itself in the foot when it comes to lessening dependence on China is regarding its infrastructure.

In the US, there is a $2.5 trillion infrastructure funding gap during the 10-year period from 2020 to 2029, based on figures provided by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). Failure to address it is estimated to result in the loss of $10 trillion in GDP by 2039.

The ASCE provides a report card for America’s infrastructure every four years. The latest, in 2021, gave the country a C-. If that sounds bad, it’s slightly better than the D+ given in 2017. A few examples of the problems facing civil engineers:

- An estimated 6 billion gallons of treated water are lost to water main breaks daily, enough to fill over 9,000 swimming pools.

- 43% of public roadways are in poor or mediocre condition.

- There are 30,000 miles of inventoried levies, and another 10,000 miles of levies whose location and condition are unknown.

While the United States in November, 2022 passed a trillion-dollar infrastructure package that includes money for roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, China is looking to outspend it by a large margin.

At Beijing’s behest, local governments have reportedly drawn up lists of thousands of “major projects,” they are being pressured to see through. Planned investment in 2022 amounted to at least 14.8 trillion yuan (US$2.3 trillion), according to a Bloomberg analysis.

That’s more than double the new spending in the infrastructure package the US Congress approved, which totals $1.1 trillion spread over five years.

According to The Economist, rather than increasing spending to address its infrastructure deficit, US government spending on it has fallen.

Consider the massive infrastructure program that Biden signed into law two years ago. Despite headlines proclaiming $1.1 trillion in investments, total infrastructure spending has fallen by more than 10% in real (after inflation) terms, as the chart below shows.

Unsurprisingly, inflation has added a huge chunk to construction project costs, which has also meant delays. The article notes that the biggest component of the infrastructure package was a 50% increase in funding for highways to $350bn over five years. But highway construction costs soared by more than 50% from the end of 2020 to the start of 2023, in effect wiping out the extra funding.

Another problem is “Buy America” rules requiring builders to source materials at home, along with touchy-feely requirements to promote racial equality, fair wages, and environmental sustainability. “The administration is at war against itself,” the article quotes a consultant and former general counsel in the Transportation Department.

The law also included more than 100 new competitive grant programs, which require new application systems and new compliance procedures. “These are a nightmare to set up and run,” Mr Gribbin says. Some state and local officials are not even bothering to apply for funding.

America’s separation of powers between the federal government and the states has also thrown a wrench into infrastructure improvements:

There is a substitution effect as the arrival of federal money allows states to step aside and spend less on construction. A recent wave of tax cuts by states has been made possible in part by the gusher of federal cash.

Getting permits is another obstacle, familiar to those in mining. As the article states:

The Biden administration has created a special action plan to try to speed up approvals for infrastructure and clean-energy projects. At the same time, though, its appointees in the Environmental Protection Agency have given states more power to block infrastructure projects because of fears about water quality. “The administration’s record on permitting is mixed at best,” says Ken Simonson of the Associated General Contractors of America.

Project Syndicate reported recently that President Biden “missed an opportunity to help America — and himself” by not canceling the Trump tariffs on Chinese imports.

The article notes that in 2017, the last year before Trump’s tariff hike, US imports from China amounted to $506 billion, about 22% of total imports. “Every serious study of the issue suggests that the increased costs arising from the tariffs have been passed onto American consumers.”

Not only consumers, but businesses.

“About 40% of US imports from China are parts, components, and intermediate goods, so removing the Trump tariffs would also lower input costs for American service providers and manufacturers. As a result, the prices of many American-made products and services in the US household-consumption basket would also decline.”

An argument could be posed that Democrats cannot do trade agreements because they are against free trade. Recall that America led the effort to create the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade pact whose goal was to counter China’s influence. One of President Trump’s first acts was to pull the US out of the TPP, and President Biden is closer to Trump’s way of thinking than Obama’s.

As Bloomberg states, so the best course — joining CPTPP, the successor to TPP — wasn’t on the table. IPEF promised to be the next best thing, a so-called skinny trade deal (meaning regulatory convergence, not lower tariffs) plus promises of cooperation on supply-chain resilience, environmental policy, tax compliance and anti-corruption efforts…

There’s no clear rationale for the administration’s new policy if you can call it that. Politics appears to have played the leading role, with many Democrats affirming their opposition to free-trade agreements on principle…

Beijing will see the stalling of IPEF as excellent news. China is striving to exercise leadership in the region through its own network of closer trade arrangements and has asked to join CPTPP. By turning its back, the US stands to lose not just the economic benefits of closer cooperation on trade but also the geopolitical gains from restoring its leadership in setting rules and, above all, conducting itself as a consistent and reliable partner.

Conclusion

China understands that mining is the lynchpin that enables an economy to move from low-tech producer of inexpensive goods for export, to high-tech manufacturer of goods and services the future world economy needs. Because they have the raw materials.

We weren’t paying attention when China cornered the rare earths market back in 2010 and were also blind to the Chinese locking up global supplies & processing capabilities for nickel, cobalt, graphite, lithium, steel and now, copper.

Canada’s politicians preferred to export raw materials, mostly to China, meanwhile the US and EU went all “NIMBY.” Donald Trump’s solution was to slap China with hundreds of billions worth of tariffs, which did nothing to end China’s metal monopolies, and then Biden claimed that Americans needed to invest more in infrastructure, sourcing the raw materials from Canada, and a whole host of other much less friendly places, to avoid China “eating our lunch”. Well, fact is the Chinese long ago ate our breakfast, lunch and dinner, they’ve hoovered up the whole smorgasbord.

Beyond the supply-chain dilemma of relying on China and other adversary countries, such as Russia, for our critical minerals, there are other issues that stand in the way of North America becoming critical minerals independent.

According to Project Syndicate, there are four major obstacles:

- De-globalization has more countries shifting from free trade to “secure trade” (read protectionism), and from economic integration (like the EU) to decoupling and de-risking.

- Societal aging is reducing the supply of workers, while immigration restrictions are hampering the flow of labor from poor to rich countries, both of which are increasing labor costs.

- Climate change is fueling energy and food insecurity and increasing energy and food costs.

- Escalation of the Sino-American cold war. Author Nouriel Roubini states: The recent summit in San Francisco between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Biden did not change anything structural in the collision between US and China. Despite a short-term partial détente, the cold war is becoming colder, and may eventually become hot over the issue of Taiwan.

I agree that the recent rapprochement between the West and China is temporary, perhaps even lulling us into a false sense of security, and valid only so long as China needs to cooperate with the West in areas it deems beneficial, such as semiconductors. When China feels it no longer needs the West, look for the Sino-American cold war to greatly intensify.

China’s recent move to become more self-sufficient in copper looks to be part of this strategy. It doesn’t want more refined copper, just more ore that can feed its domestic copper refineries which process the stuff locally, in much the same way it has done for lithium, graphite, steel, rare earths, nickel and cobalt.

North and South America are resource rich, just Canada and the US have enough critical, and other metals, to supply both economies for the future.

What we lack is a common-sense approach to finding and developing resources – funding for exploration/ development, streamlining and shortening the permitting process, building the infrastructure to access remote areas, using much more nuclear energy, building smelters/ refineries, acquiring the technology to manufacture products like REE magnets and battery anodes and finally building a manufacturing base.

Can the West break China’s near monopoly on critical metals? Yes, after all, China’s advantage over us is political not geological.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.