US banking crisis has gone quiet, but not away – Richard Mills

2023.09.13

It was exactly six months ago when the US regional banking crisis started to dominate news headlines, triggering concerns over the global financial system. Fast forward to today, the panic has mostly subsided, thanks in large to the financial might of the Federal Reserve, which acts as a lender of last resort to the banks.

Still, the sequence of events left us with a lot of unanswered questions. After all, emergency funds from the Fed can only paper over the cracks of the US banking system; the main forces behind the bank failures earlier this year — four to be precise — are still present, namely high interest rates. Three of those were amongst the four biggest banking failures in US history (see below).

At this point, it’s still unclear whether the US banks are really out of the woods.

There’s still lots to play out in this story; the Fed, which has its part to blame for its lenient policies and oversight, could be calling an end to the current monetary tightening cycle as soon as next year, which would be welcomed by individual banks.

However, just how much of a lifeline has the Fed given to the banks remains to be seen; some may not last until then. After all, many US banks continue to sit on deteriorating long-term assets as a result of the Fed’s rate hikes.

Growing Unrealized Losses

If we had to speculate, then it’s very likely that we’ve not heard the last of this story.

There’s one important figure we have to point to. $558 billion — that is the total amount of unrealized losses on securities held by US banks in the second quarter, according to banking data compiled by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

That represents an 8.2% increase over the $515.5 billion from the first quarter, meaning that these banks have racked up more losses since the crisis began.

To get to the bottom of this, we have to first understand what are “unrealized losses”, versus realized/actual losses. By definition, an “unrealized loss” is a decline in the value of an asset that has not yet been sold; in other words, they’re losses on paper. A bank may continue to hold such an asset in the expectation that it will gain in value, perhaps offsetting the amount of the current unrealized loss. It is only when the asset is sold that it becomes a realized loss.

So, how did US banks accumulate so much unrealized losses? The answer, as we’ve discussed above, is interest rates. This is because as the central bank continues to raise rates, the value of the banks’ assets, a lot of which were long-dated US Treasury and mortgage-backed securities that were purchased before the Fed’s tightening cycle, kept going down.

Of course, these just created paper losses, so until the banks sell these assets, these losses don’t really count. Once the bonds hit maturity, the banks would receive face value, and no loss is incurred. Under normal circumstances, the banks wouldn’t need to worry a thing.

That is unless they’re forced to sell their assets during a bank run, more so if most of their deposits are uninsured, which is exactly what happened with Silicon Valley and First Republic, which triggered the whole panic back in March.

While some may point to the fact that current unrealized losses are still lower by $131 billion from the peak in Q3 2022, those periods are hardly comparable, because the collapsed banks are longer part of the FDIC’s reported figures.

Interest Rate Impact

We can always point to each bank’s mismanagement, but in this sector no problem occurs in isolation, and interest rates certainly played a part in that.

Apart from causing the banks’ assets to depreciate, a high interest rate also increases what they have to pay to borrow, which in turn further limits their profitability and exacerbates their vulnerability to adverse events.

In the first half of the year, US banks have had to cope with low loan growth and high deposit costs. This increased cost is partly due to customers withdrawing their money and putting it into places where they can make more interest, such as money market funds.

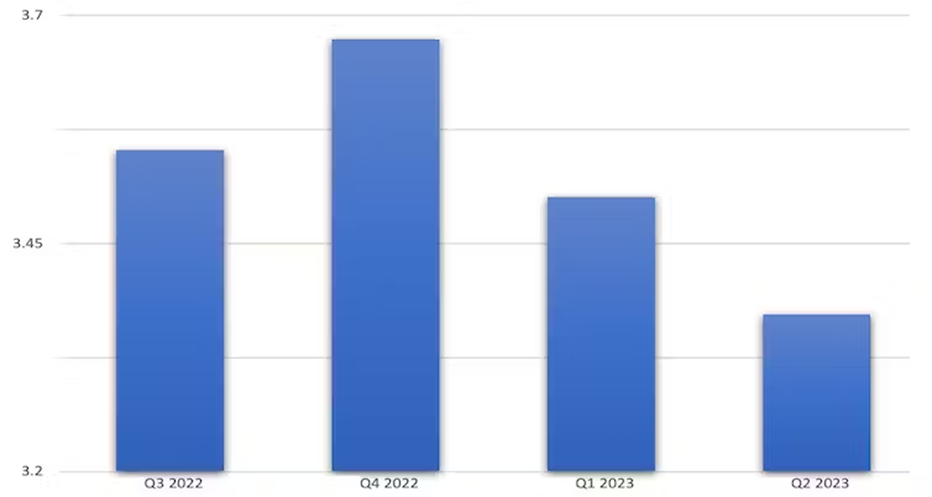

This then forced banks to borrow more from the Fed to ensure they had enough money, and at rates much higher than they used to be. The result? A decline in net interest margins for the last three quarters (see below).

The decline in profitability certainly played a key role in the banking collapses in the spring, as it destabilized the banks at a time when the value of the debt on their balance sheets had also fallen sharply. This saw more customers at other banks withdrawing deposits for fear that their money wasn’t safe either, resulting in the aforementioned bank run.

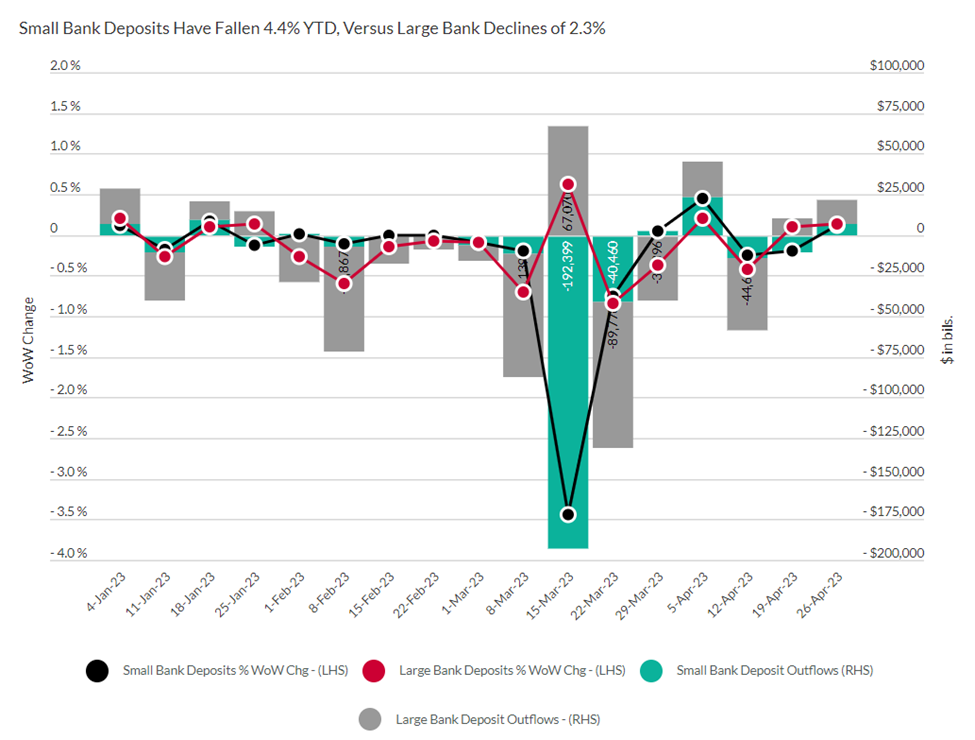

Between June 2022 and June 2023, deposits at US banks were down by 4%. Even if the crisis has seemingly been averted, that is not good news for the banking sector (see chart below).

Banks Not Safe Yet

Suffice to say, the US banking sector is far removed from being in a safe place.

A research paper cited by Moody’s Analytics noted that the US banks are more exposed to the impact of higher interest rates on the valuation of their securities than their counterparts in the UK and eurozone. This is due to the higher balances of hold-to-maturity (HTM) and available-for-sale (AFS) securities on their balance sheets.

The warnings were there even before the SVB collapse. Just days before, FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg said that the market value of US banks’ long-term assets dropped $620 billion in 2022. However, research published by Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research found that the banking industry’s unrealized losses could be more than three times that figure.

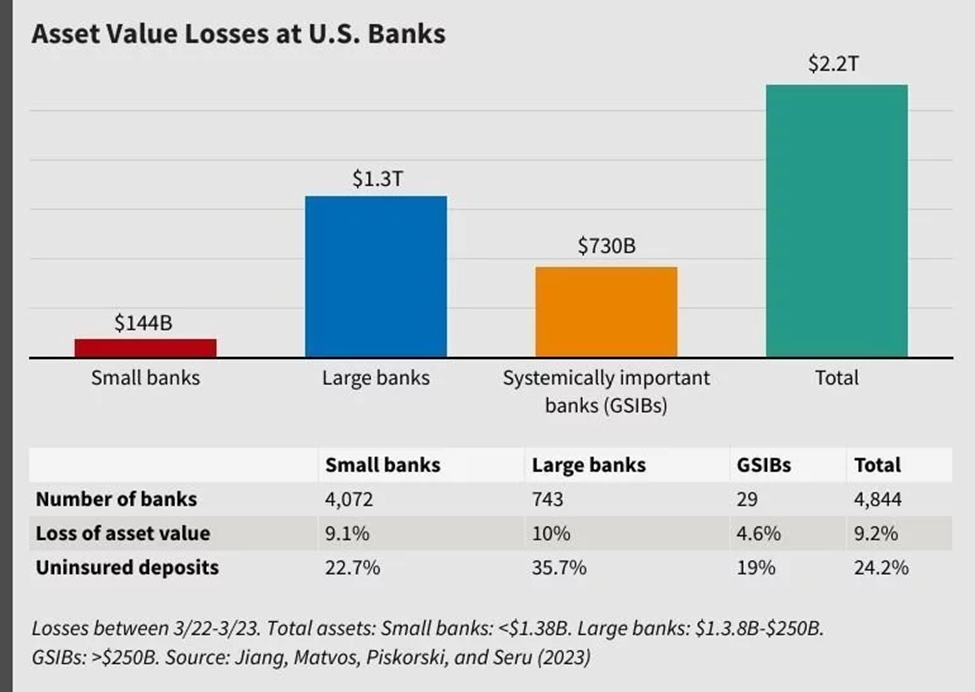

“As a result of rising interest rates, the market value of the average US bank’s assets is about 9% lower than its value on paper. Overall, the US banking system accumulated $2.2 trillion in these unrealized losses over the past year. Ten percent of banks have had larger unrealized losses than Silicon Valley Bank,” according to the study, which looked at more than 4,800 US banks to gauge their exposure to the risks that caused SVB to fail.

“While SVB had an unusually large share of uninsured depositors, other banks with high levels of uninsured depositors and large losses are also prone to solvency crises that could trigger bank runs. That, in turn, would require the FDIC to spend billions to save their insured deposits,” it added.

Amit Seru, a professor of finance at Stanford Graduate School of Business and co-author of the report, says that SVB is not an outlier, adding that “more than 500 other banks should also have failed.”

A follow-up study by the same authors estimated that almost 190 US banks are at potential risk of collapse if only half of the uninsured depositors decide to withdraw their funds. “If uninsured deposit withdrawals cause even small fire sales, substantially more banks are at risk,” it said.

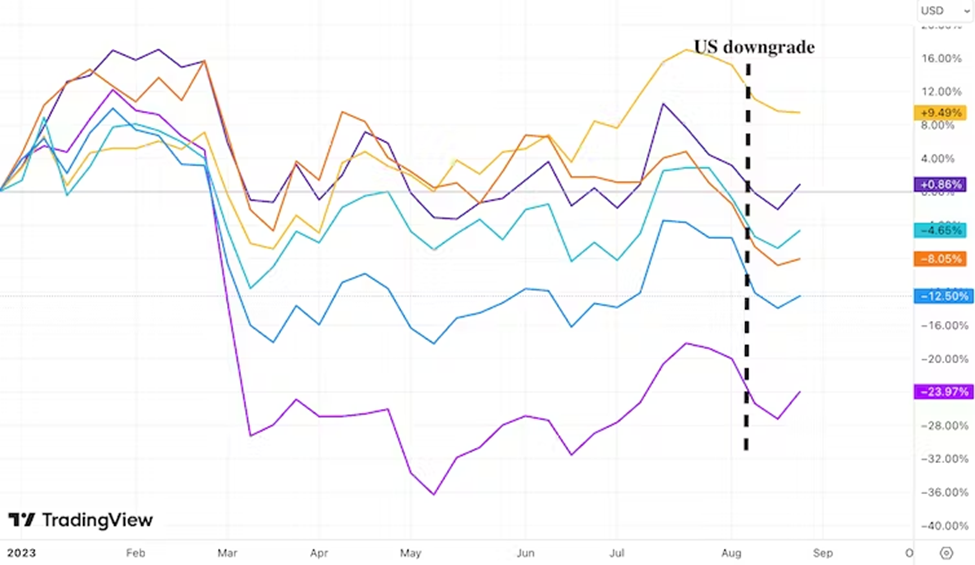

Since then, the ratings agencies have only applied further pressure. In early August, Fitch started off by downgrading its rating of US government debt to AA+ from AAA, citing a likely deterioration in the public finances over the next three years.

Sovereign downgrades can destabilize banks by making them seem less creditworthy, leading their credit ratings to be downgraded as well. In turn, that makes it harder for them to borrow money from the markets or potentially even from the Fed. The potential knock-on effects include a reduced lending capacity, decline in overall profitability and lower share prices.

Sure enough, a week after Fitch’s announcement, Moody’s downgraded the credit ratings of ten US mid-sized banks, and also warned that larger banks including Bank of New York Mellon and State Street were at risk of a future downgrade. S&P Global Ratings has since followed suit, while Fitch is threatening to do likewise.

Conclusion

Admittedly, there are some positive developments to ease the sense of panic. For starters, both interest rates and bank deposits are projected to stabilize over the coming months, which Fitch says should help the sector.

US regulators are also planning to overhaul the way the biggest banks manage their capital. A sweeping proposal — dubbed the “Basel III endgame” — was unveiled in July to raise the minimum capital requirements for banks with $100 billion in assets or more. However, these plans are likely to take more than four years to implement.

In the meantime, the US banking sector is seemingly gearing up for these stricter rules by taking a more cautious approach, with lenders holding more cash than before.

Overall, cash assets held by US banks were $3.26 trillion as of Aug. 23, up 5.4% from the end of 2022. That was well above typical pre-pandemic levels, though down from the weeks immediately following the bank failures in March, Federal Reserve data shows.

Cash assets at small and mid-sized lenders are up 12% compared with the start of the year. At the nation’s top 25 banks, cash holdings are up about 2.9%.

“A lot of banks are taking steps to reduce risk and strengthen their balance sheets,” said Brendan Browne, S&P’s senior credit analyst for financial institutions, via Reuters.

Regional banks are shifting more “earning assets,” such as those from lending activities, into cash or short-term securities, added Manan Gosalia, an analyst at Morgan Stanley who covers regional banks. “As banks see further pressure on deposit costs, and as they hold higher levels of liquidity, we expect loan growth will continue to slow as we get to the end of this year.”

Yet, despite taking a more prudent approach, time could be running out for some of the banks.

As the Stanford research paper suggested, there are literally hundreds of financial institutions at risk of collapsing. The depreciated value of their assets compared to their book value could actually be trillions of dollars more than reported, as the study implied.

The rise in the banks’ unrealized losses serves as an indication that the deep-rooted problems have not gone away.

The simple fact of the matter is, that the banks have bet big on long-dated securities that got slaughtered by high interest rates, and the bleeding has only just started. Just how much do the banks stand to lose? In this article, Wolf Richter of Wolf Street calculates that 10-year T-notes with a face value of $1 million would be worth only $778,000 in today’s market, making an unrealized loss of $220,000 or roughly 22% of the purchase price.

So, as long as interest rates remain high, which is likely to be the case until we see what unfolds in 2024, a lot of the US banks will continue to walk on thin ice.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.