6 climate tipping points – Richard Mills

2023.08.02

Earth’s climate is warming a lot faster than many had anticipated.

Climate change, a misnomer, and the correct term, global warming, are cited as explanations for why our planet is in ecological flux. This includes freak winter storms that appear to contradict the “warming” thesis, scorching heat waves, prolonged droughts, water shortages, rising sea levels, retreating glaciers, thinning sea ice, melting permafrost, dying coral reefs and the extinction of species.

While there is disagreement over its causes, the reality of global warming is an incontrovertible fact. The planet is warming, affecting our weather, oceans, growing seasons and food, as crops fail, causing shortages and price hikes. Storms are becoming more frequent and more intense. Droughts are lasting longer. Heat waves and forest fires are now annual summer occurrences.

In 2018, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned that the effects of global warming would be irreversible in 12 years. Seven years before the deadline, climate scientists are already saying, “we told you so.”

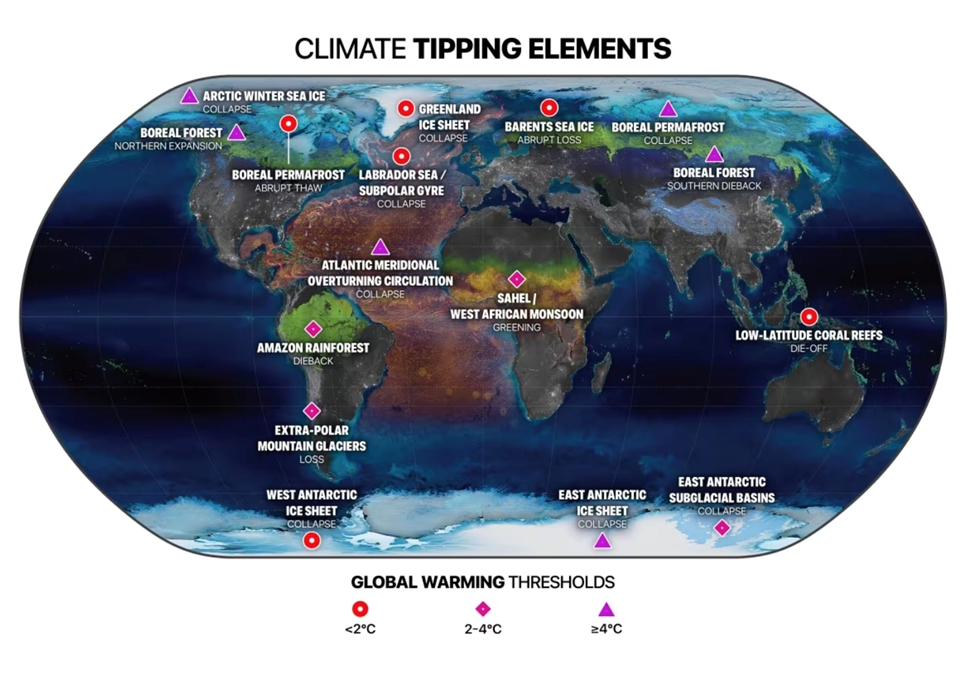

Several “tipping points” have already been passed or we are on the brink. A tipping point is when we can no longer return to normal climate patterns and conditions will worsen.

The difference between a tipping point and a gradual change, such as progressive warming, is the irreversibility of it. “[Tipping points] can happen suddenly, like an on-off switch, pushing climate systems into a completely new state. And they’re generally irreversible or difficult to reverse,” states a recent CBC article on one of the tipping points, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

Here we take a deep dive into global warming tipping points, by identifying and explaining six: record heat; warming oceans; the AMOC collapsing within our lifetime; the polar vortex/ jet stream breaking down; the loss of Arctic/ Antarctic sea ice, and the retreat of polar ice sheets; and thawing permafrost.

Record heat

According to data from the University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer, a new daily global record of 62.9 degrees Fahrenheit, or 17.18 Celsius, was set on July 6.

It was also the hottest week on record. For the seven-day period ending on June 28, the average daily temperature was .08 degrees Fahrenheit (.04 C) warmer than any week in 44 years of record-keeping.

While the records are based on data that only go back to the mid-20th century, a senior climate scientist at Woodwell Climate Research Center quoted by one media outlet said they are “almost certainly” the warmest the planet has seen over a much longer time period – “probably going back at least 100,000 years.”

The same climate scientists are saying the heat is set to continue as the planet keeps warming. “A record like this is another piece of evidence for the now massively supported proposition that global warming is pushing us into a hotter future,” Stanford University’s Chris Field commented.

Indeed, with the calendar turned to August, July will unofficially be the hottest month ever recorded. A new study quoted by CBC News found the past month had 23 consecutive days of record global temperatures, thus surpassing by a “considerable margin” the previous record set for July four years ago.

A chart in the CBC article has July 2023’s 16.95C topping the warmest months on record globally.

Examples of heat records set in North America and Asia:

- Death Valley, California saw the hottest night ever recorded globally. Between 12 and 1 am on July 17, the Badwater Basin weather station recorded temperatures of 48.9 degrees Celsius, or 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Phoenix, Arizona saw 28 days in a row of temperatures exceeding 43.3C, while in San Antonio, Texas, it was at least 38C for 15 straight days.

- China’s Sanbao township hit a high of 52.2, breaking the national record.

Paleoclimate research, using indicators like tree rings and ice cores, shows the last time the Earth was this warm was 120,000 years ago.

In Canada, the extreme heat has led to unusual weather, such as tornadoes in Alberta, flooding in Nova Scotia, and the worst year for forest fires on record. As of July 27, there were 1,072 fires burning across Canada in almost every province and territory with 12.1 million hectares burned so far in 2023 — more than double the previous record set in 1994.

As for how soon global warming will reach 1.5 degrees C, the so-called tipping point, the World Meteorological Organization predicts there is a 66% chance of exceeding 1.5 degrees above the 1850-1900 average for at least one of the next five years. So far the Earth has warmed about 1.1 degrees, to 1.3 C.

According to a 2018 study in Lancet Planetary Health, via Bloomberg, as many as 50 million people could regularly see temperatures that the human body isn’t equipped to survive. In African cities such as Algiers, up to 52 times more people would face dangerous heat, the study says, while the amount of wildfire area burned globally would double, as planetary warming turns rainforest into grassland.

When temperatures are rising so fast that extreme heat becomes a common occurrence in several parts of the world including our own (Western Canada), plant growth is stunted, leading to lower crop yields and in worst cases, the destruction of the entire crop.

The wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) considers not only the air temp and humidity, but the wind speed, sun angle and solar radiation levels.

Between 80 and 88 degrees Fahrenheit WBGT, working in the sun for more than 45 minutes put the body under serious stress. About 88 WBGT, the window of safety closes to 20 minutes. Above 90, being active in the heat becomes dangerous after 15 minutes and reaches a point in the 90s where you shouldn’t be doing anything outside.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says rising causes of death would include not only the heat, but exposure to ground-level ozone, malaria, dengue and West Nile virus.

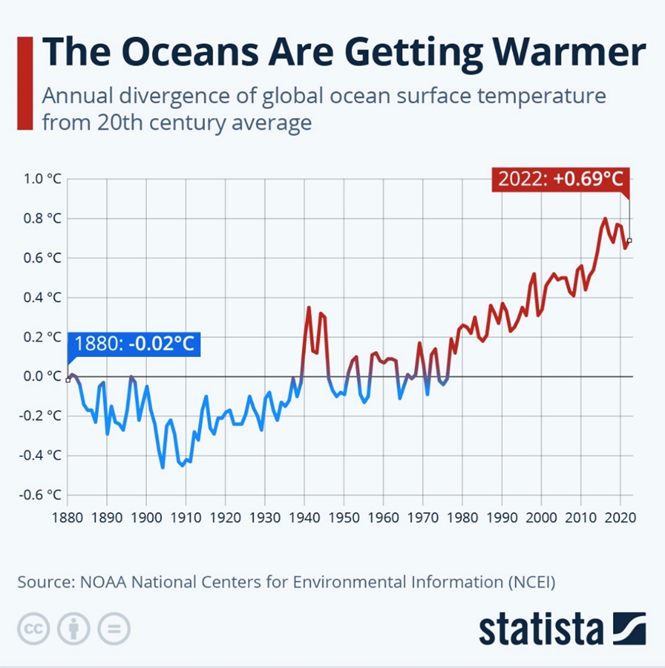

Warming oceans

The heating up of the world’s oceans is one of the most damaging aspects of climate change. The phenomenon is driving weather disasters around the world, including extreme heat, storms and drought.

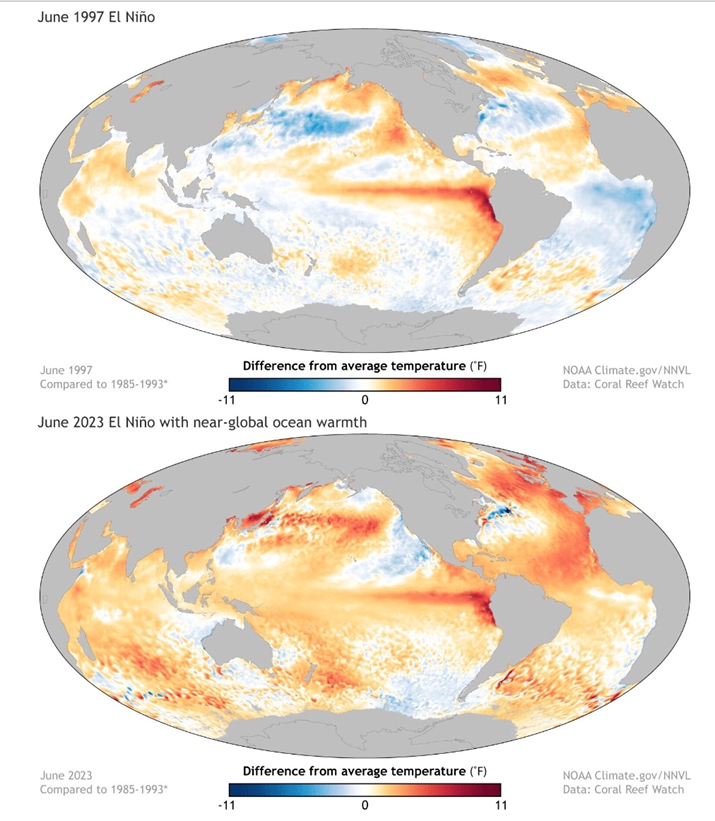

A recent media report says Global ocean surface temperatures in June were the highest in 174 years of data, with the emergence of the El Nino weather pattern piling onto the long-term trend. Near Miami, coastal Atlantic waters are pushing 90F (32C).

According to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, the extreme heat wave that blanketed the southern United States and Mexico in June, combined with ocean temperatures soaring to alarming levels.

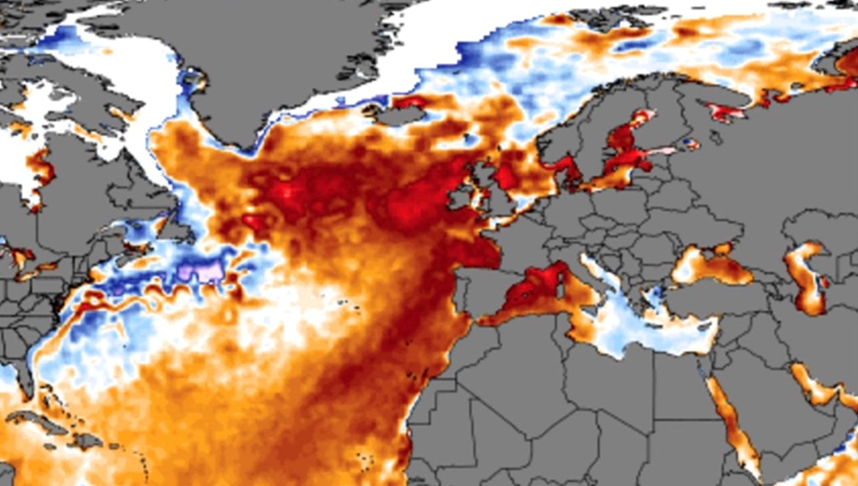

NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, reported in June that surface temperatures in the North Atlantic were up to 5 degrees C warmer than usual. The same thing is happening in Antarctica, where scientists have linked warm waters off the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic oceans to plunging sea ice levels.

Source: Climate Change Institute/ University of Maine

The Globe and Mail said parts of the continent and nearby ocean were 10 to 20 degrees Celsius higher than averages from 1979 to 2000.

Another related climate phenomenon that is behind the record heat, is the switch from “La Nina” to “El Nino”.

It’s been well-established that warmer, or colder-than-average ocean temperatures have an influence on weather. According to the NOAA, El Nino causes the Pacific jet stream to move south and spread further east. During winter, this leads to wetter conditions than usual in the southern US and warmer and drier conditions in the north.

El Nino is shorter-lived than La Nina, usually lasting nine months to a year versus a few years for the cooling phenomenon. El Nino is said to be warming up the eastern Pacific Ocean, and is forecast to intensify and linger to at least the end of the year, resulting in higher global temperatures. The World Meteorological Organization officially confirmed the arrival of El Nino on July 5.

Most forecasters believe that, with El Nino kicking in across the Pacific Ocean, Western Canada could be dry for months, possibly even approaching the parched conditions the southwestern United States has been experiencing for the last 20-odd years.

Warmer temperatures and overfishing are pushing temperate species towards the poles where they face greater competition for food with polar animals. Warmer ocean temperatures also cause acidification, which stunts the growth of corals and shell-based creatures like oysters. The destruction of coral reefs is a major problem resulting from global warming, since they provide critical habitat and food for so many species in the reef ecosystem.

Another result of rising surface ocean temperatures is a reduction in the numbers of phytoplankton, which since 1950, have declined globally by about 40%. The decline in phytoplankton could make the problem of over-fishing even worse, since phytoplankton are eaten by zooplankton, which is consumed by fish further up the food chain.

Half of the world’s oxygen comes from phytoplankton. They are vital in maintaining the Earth’s atmosphere and the oxygen we need to survive. Phytoplankton also absorb a huge amount of carbon dioxide.

As temperatures in the ocean and atmosphere rise, mass coral bleaching and infection disease outbreaks are becoming more frequent, states the NOAA.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the world’s oceans have lost half of their coral reefs since 1950. Scientists in a 2021 study said overfishing and pollution, when added to climate change, are decimating these fragile ecosystems and putting communities and livelihoods in jeopardy.

Examples of extreme weather fueled by warmer oceans are hurricanes and typhoons. Soaring water temperatures supercharge storms by adding moisture to the atmosphere.

The Bloomberg story said global accumulated cyclone energy was almost twice the normal power for June. The North Atlantic hurricane normally starts in September, but two storms happened in June for the first time in five decades. In July, a Colorado State University researcher cited warmer oceans as the reason for boosting this year’s Atlantic hurricane season forecast to 18 storms from 14 in June.

The phenomenon also has a major impact on land. As oceans heat up, they cause higher land temperatures, which contribute to hotter seas (an example of a climate “feedback loop”).

We have already seen several effects of this feedback loop over the summer. They include heavy rainfall that unleashed flooding across the US northeast in July; blistering heat in the southern United States, Europe and Asia; scary-low river water levels on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, the Rhine and the Danube, that are affecting shipping on important freight routes; and droughts that threaten global supplies of crops including sugar cane and rice.

In Canada, a shift in the jet stream (see section below) has kept rainfall to an absolute minimum, leading to drought and the worst wildfire season on record. Smoke from Canadian fires has drifted south into major American cities, impacting air quality and visibility. In BC, severe drought conditions across the province are forcing cattle ranchers to consider selling their herds due to skyrocketing hay costs.

Yet if things look bad now, they are only likely to get worse:

As oceans heat up, they are also less able to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, said [marine scientist Deborah] Brosnan. That could create a cycle of warming oceans, more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and, as a result, ever-more extreme weather.

Polar vortex breakdown

The polar vortex is a seasonal atmospheric phenomenon whereby high winds swirl around an extremely cold pocket of Arctic or Antarctic air. The winds are like a barrier that contains the cold air, but when the vortex weakens, the cold air “escapes” from the vortex and travels south, bringing with it a cold blast of Arctic weather. If the polar vortices collapse, it would mean a total disruption of normal atmospheric warming and cooling. Without halos of swirling Arctic and Antarctic winds serving to cool the poles, they would be left to heat up, accelerating global warming.

The blast of cold weather that hit North America in January 2019 exemplifies this polar vortex breakdown. The Arctic polar jet stream meandered southward, bringing freezing-cold weather to the US Midwest, which saw windchills of -50F, along with fatalities and problems with the power grid in other parts of the country.

According to IFL Science, while it’s uncertain how climate change might meddle with the polar jet stream, Scientists believe the most likely outcome is that warming temperatures will initially cause the jet streams to “wave” more, causing polar air to visit the mid-latitudes more frequently, ultimately bringing more periods of colder weather.

Notably, a wandering polar jet stream can also cause extreme heat, such as the “heat dome” experienced by Western North America in the summer of 2021, that killed 619 people in British Columbia alone.

Heat domes can occur when winds in the upper atmosphere, also known as the jet stream, are influenced by the ocean below. Hot seas cause the winds to shift, resulting in areas of high pressure that trap hot air in place for weeks.

Slowing currents

Climate scientists have been raising concerns that rising temperatures could throw a wrench into the conveyor-like currents system. The volume of water moving northward has been sluggish. The amount of water surging through the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which exchanges warm water from the equator with cold water from the Arctic, transporting warm and cold water to the North and South Poles, has slowed to a 1,000-year low. The disruption of the North Atlantic Current formed the plot line of the movie ‘The Day After Tomorrow’, where the current stopped and resulted in an ice age.

While it’s unlikely that a collapse of the AMOC will cause an ice age within a few weeks, like in the film, a terrifying new analysis found that a breakdown could occur as early as 2025, and no later than 2095.

As reported by The Guardian, the AMOC was already known to be the weakest in 1,600 years owing to global warming, and researchers spotted signs of a tipping point in 2021.

The reason it’s slowing is due to the melting of Greenland’s ice cap. Specifically, dense salt water in the North Atlantic is getting swamped by an influx of lighter fresh water from the melting ice.

The Guardian says a collapse of AMOC would have wide-ranging consequences, including: severely disrupt the rains that billions of people depend on for food in India, South America and West Africa, increase storms and drop temperatures in Europe, raise sea levels on the eastern coast of North America, and further endanger the Amazon rainforest and Antarctic ice sheets.

Source: Zhengyu Liu/ CBC News

The last time the AMOC shut down was 12,000 years ago, resulting in a cycle of ice ages.

If it were to happen again, CBC reported that England and France would suddenly get a colder climate similar to southern Canada, damaging those countries ability to grow food; heat up northern Africa; and bring more storms and cause changes to rain and snow in Eastern Canada and the US, including drying of the mid-American plains.

The study says the collapse will happen far sooner than the previous estimate, a tipping point of +4 degrees C.

Loss of ice

The warming of the Earth’s surface has caused a widespread retreat of the glaciers at both poles. Arctic and Antarctic sea ice has also thinned out considerably.

The latest IMBIE assessment (IMBIE stands for Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise), published in April, found that between 1992 and 2020, the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets lost 7.5 trillion tonnes of ice – equivalent to an ice cube measuring 20 km each side.

The two ice sheets together are responsible for more than a third of total sea level rise.

Other interesting facts provided by the European Space Agency regarding the polar ice sheets:

- Together they have lost ice in every year of the satellite record, and the seven highest melting years have occurred in the last decade.

- Melting peaked in 2019, when the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets lost 612 billion tonnes of ice due to a summer heatwave in the Arctic.

- In the early 1990s, ice sheet melting accounted for only a small fraction (5.6%) of sea-level rise. However, there has been a fivefold increase in melting since then, and they are now responsible for more than a quarter (25.6 %) of all sea-level rise.

- If the ice sheets continue to lose mass at this pace, the IPCC predicts that they will contribute between 148 and 272 mm (5.8 to 10.7 inches) global mean sea level by the end of the century.

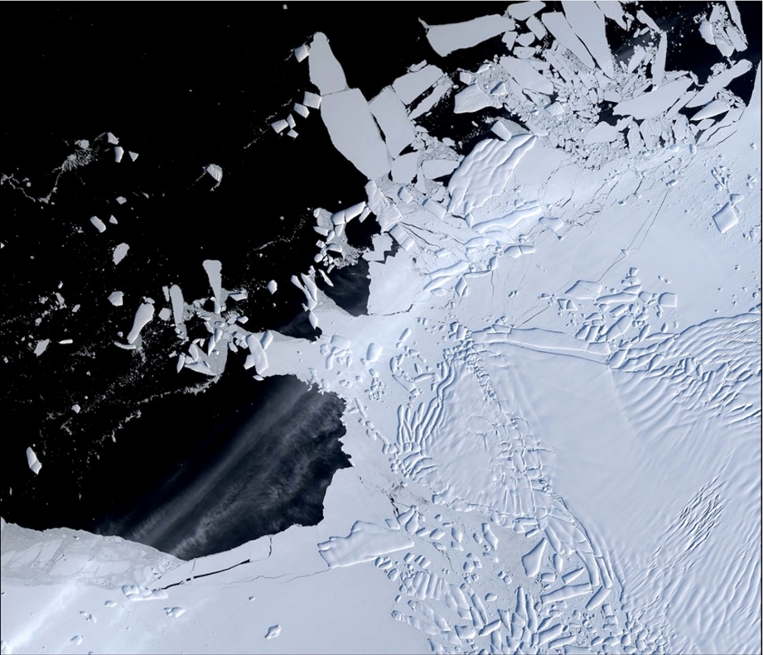

According to the above Bloomberg piece, Antarctic Sea ice reached its lowest June extent on record. In February 2022 it was below 2 million square kilometers for the first time since measurements began in 1979.

Fast-forward a year later, a new record of 1.79 million square kilometers was set, representing the third time this record has been broken in six years.

One major area of concern is a marked loss of ice around the Amundsen and Bellinghausen seas on the continent’s west. Even as the average amount of sea ice around the continent grew up to 2014, these two neighboring seas saw losses, satellite data shows.

That’s important because the region is home to the vulnerable Thwaites glacier — known as the “doomsday glacier” because it holds enough water to raise sea levels by half a meter.

“We don’t want to lose sea ice where there are these vulnerable ice shelves and, behind them, the ice sheets,” Matt England, an oceanographer and climate scientist at the University of New South Wales, said.

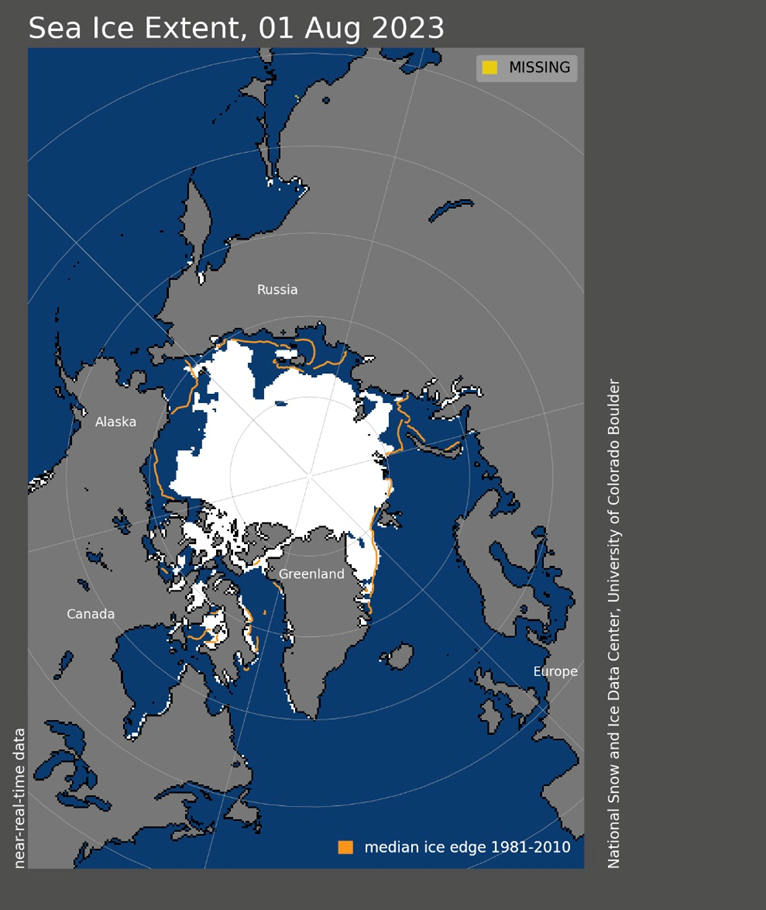

The UN Environmental Programme says the situation is far more dramatic on the opposite side of the planet. While 40 years ago Arctic Sea ice was three to four meters thick, it is today around 1.5 meters.

In fact the Arctic is heating up four times faster than the rest of the world and much of this has to do with the loss of sea ice.

New research has found that the Arctic could be almost free of sea ice during summer by the 2030s – roughly a decade sooner than previously thought. Scientists say that even if extreme emission-reducing steps were taken, it is now too late to save the region’s summer ice.

Prof. Dirk Notz, of the University of Hamburg, Germany, who was part of the research team, told The Guardian: “As scientists, we’ve been warning about the loss of Arctic summer sea ice for decades. This is now the first major component of the Earth system that we are going to lose because of global warming. People didn’t listen to our warnings. This brings another warning bell, that the kind of projections that we’ve made for other components of the Earth system will start unfolding in the decades to come.”

According to UNEP, Thinner ice and more open water led to increased absorption of sunlight and increased melting in summer. Since 1979 around 50 per cent of summer sea ice coverage has been lost.

As for Arctic winter sea ice, UNEP says ice-free conditions before the end of the century will only occur in the Barents Sea, but significant winter loss in many of the Arctic seas is projected.

The greatest amount of Arctic warming seems to be taking place on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Arctic Ocean near the Barents Sea.

According to the National Snow & Ice Data Center, Arctic Sea ice is currently about 1.3 million square kilometers below the 1981 to 2010 reference period, and ice extent in mid-July was 12th lowest in the 45-year satellite record. However, several regions have far below average extent, including the Kara and Beaufort seas, and Hudson Bay, which became ice-free “quite early this year”.

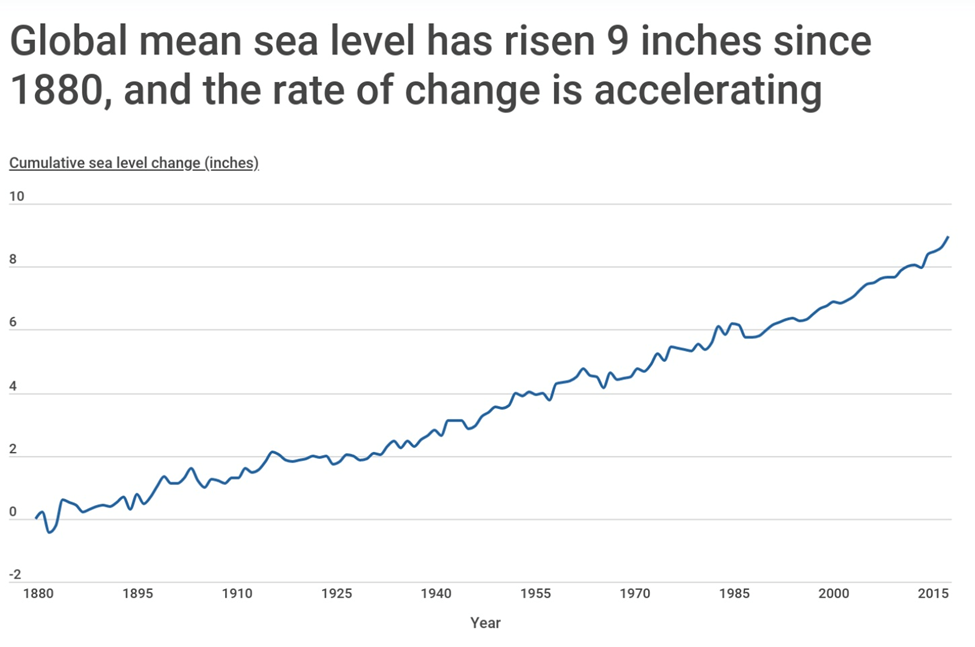

All this melting ice, along with the expansion of ocean water as it warms, has caused sea levels to rise. Global mean sea levels have already risen between 8 and 9 inches, or 21-24 cm, since 1880, according to NOAA.

The 2019 International Panel on Climate Change report predicts sea levels rising between 28 cm (0.95 feet) and 110 centimeters (3.6 feet) by 2100 if temperatures don’t stop rising. An increase of 65 centimeters, or roughly two feet, is expected to cause significant flooding in coastal cities.

The sea level along the US coastline, for example, is projected to rise between 10 and 12 inches, on average, from 2020 to 2050.

Government statistics show 40% of the US population lives in coastal areas vulnerable to sea level rise. From a list of 25 US cities likely to be swallowed up by the sea, the most at-risk states are Florida, California, Virginia, South Carolina, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Hawaii.

Thawing permafrost

Along with calving glaciers, shrinking ice caps, and disappearing sea ice, evidence of Arctic warming can also be seen in the thawing of permafrost. Permafrost is land that is permanently frozen except for the top layer, which freezes in the winter and thaws in the summer; 70% of Russia sits on permafrost, which in some areas is over a kilometer deep. When it thaws, permafrost exposes carbon dioxide and methane, a greenhouse gas that is about 30 times more powerful than CO2, in terms of its ability to trap heat.

It is estimated that this phenomenon could release between 300 million and 600 million tons of net carbon per year into the atmosphere.

Another negative impact of thawing permafrost is subsidence. This is what happens when the surface layer gets deeper, and structures (like houses and industrial buildings) on or embedded in it start to fail as the ground beneath them expands and contracts.

Climatologists predict that an estimated 2.5 million square miles of permafrost, or 40% of the world’s total, could disappear by the end of this century, significantly accelerating global temperature rise.

Thawing permafrost is also dramatically altering the Arctic landscape. A 2022 article by The Conversation describes several massive lakes disappearing in the span of a few days, leaving the once-flat geography wavy and creating vast fields of large, sunken polygons. (see below)

Earlier we introduced the concept of a feedback loop. Here another one occurs, when microbes released by the thawing ground begin eating organic matter that has been frozen for millennia. The microbes release carbon dioxide and methane. Warmer temperatures thaw more soil, releasing more organic material to feast on, producing more greenhouse gases.

The trapped organic material is what presents the most danger when it comes to permafrost thawing. Right now, nearly half of global soil organic carbon is stored in these frozen soils (and permafrost is estimated to hold twice as much carbon as the atmosphere), but according to The Conversation,

The abrupt transitions we’re seeing today – lakes becoming drained basins, shrub tundra turning into ponds, lowland boreal forests becoming wetlands – will not only hasten the decomposition of buried permafrost carbon, but also the decomposition of above-ground vegetation as it collapses into water-saturated environments.

Climate models suggest the impacts of such transitions could be dire. For example, a recent modeling study published in Nature Communications suggested permafrost degradation and associated landscape collapse could result in a 12-fold increase in carbon losses in a scenario of strong warming by the end of the century.

It’s not only the loss of carbon that can result from thawing permafrost. The newly exposed organic matter may contain long-dormant viruses that could endanger animal and human health. Chemical and radioactive waste dating back to the Cold War also has the potential to harm wildlife and disrupt ecosystems, CNN reported recently.

Conclusion

The effects of global warming are many and obvious.

Forest fires are an annual occurrence in Australia, California and Western Canada. In the United States and the Caribbean, people live in fear of the next hurricane that could literally turn their lives upside down. Most of us have watched videos of huge chunks of ice breaking off millions-year-old ice sheets and tumbling into the sea.

Global warming is not a temporary phenomenon that we can stop through government policies in partnership with industry, like carbon taxes and cap and trade schemes. Unfortunately, it’s more like a runaway train that is reaching the crest of a hill, before it begins to accelerate, at break-neck speed. It is unstoppable. The Earth will warm until it starts cooling. The proof is in the geologic record. All we can do is try to manage the effects as best we can.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.