Monumental shift in way junior mining stocks are valued is coming – Richard Mills

2023.03.01

You know it’s interesting. While much of the investing “herd” is focused on how much the stock market will rebound, quietly, behind the scenes, something else is going on.

Amid de-globalization and the rise in geopolitical tensions, the need to quicken the energy transition and secure critical minerals supply has increased apace, and it comes on the heels of a decade of chronic underinvestment in the sector, thus magnifying the level of capital investment required.

Our last article suggested we are entering a Golden Age of critical materials. This article takes a deep dive into what is driving this trend — that is, global automakers cutting deals with mining companies, to ensure they have a steady, uninterrupted supply of the metals needed for them to make the shift to electrification, and to meet the decarbonization targets set by governments.

The Golden Age of critical materials

The latest edition of the TSX Venture 50 list shows investors are increasing loading up on stocks with an energy-transition theme.

Unsurprising to me (I was Ahead of the Herd, writing this was going to happen, see centered article link below), is how well mining did last year. The sector grew 174% compared to 34% combined growth among other sectors, driven, in part by sudden increased investor interest in the critical minerals and metals space.

$2.85 trillion in new US spending bolsters bull market in electrification & decarbonization metals

Another pat on the back goes to yours truly, AOTH, for correctly anticipating that the world’s biggest car companies would, in their fear of getting left behind, start pairing up with mining firms, either signing offtake agreements or buying ownership stakes in miners, that can provide production guarantees for hugely in-demand battery/ electrification metals such as copper, lithium, nickel and graphite.

EV-makers connect with mining companies to ensure adequate supply of battery raw materials

This is exactly what we see happening. These are critical materials that automakers now realize they could easily run short of — not only hamstringing their attempts to shift production platforms from ICE to electric, but putting them at risk of expensive fines, for failing to meet decarbonization targets set by governments.

For decades, carmakers only bothered to manage their direct suppliers, which in turn worked with tier 2 suppliers, and so on up the supply chain. In the EV supply chain, battery producers and mineral processors sit between the car companies and miners. Now these companies are going right up the chain to the mines themselves, both to secure the supplies and to ensure ethical and emissions standards are met. (The Financial Times, Nov. 14, 2022)

The change is unprecedented. For the auto industry, it’s a chance to lock in security of supply and unlock themselves from China’s dominance over the battery industry amid rising geopolitical tensions. For the mining firms, it’s giving unfettered access to 1. a supply chain that all but guarantees steady demand for their metal end-products, that will last as long as the technologies underlying vehicle electrification do not fundamentally change and 2. unbelievable amounts of money for project development.

Metals freakout

For the past year or so, attention has turned to the shortfall of raw materials that is limiting the production of electric vehicles. Simon Moores, the influential CEO of Benchmark Minerals Intelligence, has said that carmakers may have to get involved in mining if they want to make electric vehicles at scale.

Moores added that, while lithium’s major producers have large investments planned, those alone will not be sufficient and new mines are needed.

His thoughts are echoed by one of the most influential voices in mining, Robert Friedland. At an African mining conference, the Ivanhoe Mines founder pointed out the problem with renewable technologies is they are incredibly energy- and metals-intensive.

“We’re going to have a freakout as we try to change the world economy unless we develop a lot more mines,” said Friedland in a 2022 Mining.com report.

According to his data, a 1,000-pound electric vehicle requires 500,000 pounds of raw materials. “So, to transition just the world’s passenger cars to electric, we have to mine more materials in the next 30 years that we mined throughout human history,” he said.

Automakers investing in mines

If more mining does occur, it will likely take place with the full support of the auto industry. Last summer a report by Fitch Solutions, via Mining Weekly, said automakers are increasing their upstream investments and supply contracts to secure enough battery metals, such as lithium, cobalt and battery-grade nickel, to drive forward their respective electric vehicle (EV) policies and to meet the decarbonisation targets set by governments globally.

Since the start of 2021, 21 such investments have been made – 16 of which were investments into lithium. These investments were made by BMW, General Motors (GM), Tesla, Stellantis, Renault, Volkswagen (VW), Toyota, BYD and Ford.

Fitch Solutions also counted some investments by mining companies whose projects will directly supply materials to EV manufacturers. These include projects led by mining companies Zijin, which will supply to Geely and BYD; Livent, which will supply to BMW and Tesla; Posco, which will supply to Rivian and GM; and Rio Tinto, which will supply to Stellantis and VW…

Fitch Solutions notes four investments by automakers into nickel mining. These were Tesla’s investment into a nickel mine in New Caledonia and PPES’s [Prime Planet Energy & Solutions] deal with diversified miner BHP, both of which occurred in October [2021].

In addition, VW announced [last] March that it would set up two joint ventures (JVs), with Huayou and Tsingshan, to secure nickel and cobalt supplies for EVs in Indonesia.

The firm also highlights an investment of $9-billion by the largest EV battery manufacturer LG Chem into an EV minerals project, in Indonesia, [last] April.

Cobalt, a crucial battery material, is suddenly superabundant

This article was posted on July 6, 2022. Up to Nov. 14, 2022, there have been even more deals reached between miners and carmakers. How many? According to the Financial Times, 52, mostly involving lithium, cobalt and nickel, but also copper, aluminum, graphite and rare earths. The agreements range from MOUs to equity investments to binding and non-binding off-takes.

Also note that prior to 2021, there were only two upstream investments by automakers – the first in 2017 by China’s Great Wall Motors into Pilbara Minerals’ lithium project in Western Australia; and the second by Toyota, which became a 15% shareholder of Orocobre, developing the Olaroz lithium project in Argentina.

Mining Weekly reports Fitch saying the overwhelming focus on lithium investments is due to the lithium mining sector being undeveloped compared to nickel. The firm estimates EVs will be responsible for more than 80% of global lithium demand by 2030, compared with only 19.3% of global nickel supply. Over two-thirds of global nickel production is used to make stainless steel, whereas EV batteries only consume 7.2%.

For years I’ve been saying that we live in a finite resource world, natural resources are not limit-less, as most politicians touting the green transition seem to think. For example there is no green energy shift without copper, needed in greater abundance in EVs than traditional vehicles, and non-substitutable graphite, used in the battery anode. Apparently, the auto industry agrees with me.

“We’re absolutely convinced that this is a race, a zero-sum game and resources are a finite limit,” Tanya Skilton, director of purchasing for electric vehicle critical materials at General Motors, told the FT Mining Summit last June.

Skilton also forecast that the industry will be divided into winners and losers based on which companies will have the minerals to fulfil their “electrified dreams”.

Five years ago, the idea of a bunch of car company executives attending a mining investment show would have seemed incongruous. In today’s lean environment for critical metals, it’s becoming common. A Feb. 24 Bloomberg headline reads, ‘Tesla, GM among carmakers flocking to mining events amid battery metals scramble’.

The article says Tesla, GM and Ford are among the major US firms expected to be mingling with mining industry executives at a major mining conference in Florida this week, along with Rivian Automotive and European counterparts Stellantis, Mercedes-Benz Group and Jaguar Land Rover Automotive.

A spokesman for the show organizer, Bank of Montreal (BMO), said he sees strong interest from several car manufacturers, who want to secure supplies of lithium, nickel, graphite and other battery meals.

“There’s an urgency to it now that wasn’t there a few years ago,” Bloomberg quoted Ilan Bahar, co-head of global metals and mining business at BMO Capital Markets.

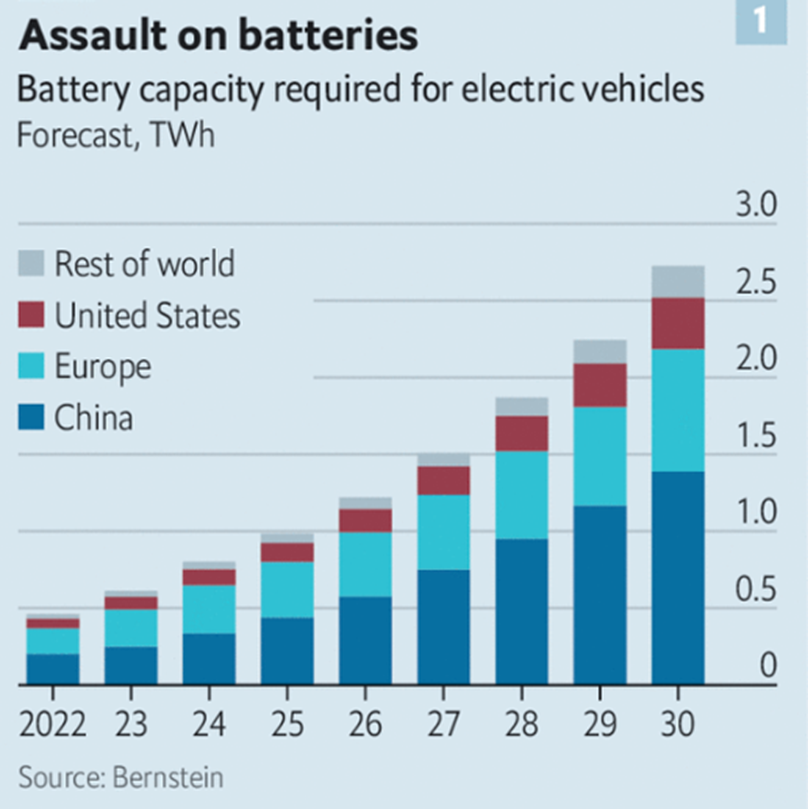

Part of that urgency comes from the fact that the investment needed to meet the demand for battery metals is huge. According to the International Energy Agency, soaring EV battery demand will require 50 new lithium projects, 60 nickel mines and 17 cobalt developments by 2030. Andy Miller, COO Benchmark Mineral Intelligence said “At the average size of graphite mines of 56,000 tonnes per annum, the industry needs some 97 new mines and 52 new synthetic plants (average 57ktpa) to meet 2035 demand.

Bloomberg also says Industry specialists warn that miners simply don’t have access to the cash needed to meet demand for battery metals, so automakers will have to pitch in.

Worried

We’re entering a Golden Age of critical materials, driven by the need for electrification and decarbonization metals such as copper, lithium, nickel and graphite. Automakers and battery manufacturers are seeking secure supplies of these metals, because they realize they are in serious danger of running out of them. They can’t allow that to happen as it would completely derail their electrification agendas, towards which they are spending billions.

Failing to electrify also risks damage to their reputations and potentially, exposure to expensive fines levied by unsympathetic governments intent on fulfilling their climate goals.

Everyone’s worried because according to the International Energy Agency, soaring EV battery demand will require 50 new lithium projects, 60 nickel mines and 17 cobalt developments by 2030.

A White House report on critical supply chains showed that graphite demand for clean energy applications will require 25 times more graphite by 2040 than was produced in 2020.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance (NEF) estimates that in 20 years, the world’s copper miners must double the amount of global production — from the current 21 million tonnes annually to 40 million tonnes — just to match the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles.

The World Bank’s 2020 Minerals for Climate Action report says demand for copper, cobalt, zinc, silver and lithium could increase by almost 500% by 2050. According to the International Energy Agency, an electric car today requires six times the mineral inputs of a gasoline-powered vehicle, while an onshore wind farm needs nine times the volume of a gas-fired power plant.

Conclusion

“In the 1920s Henry Ford set up rubber plantations in the Amazon, a steel mill in Michigan and coal mines across the US to supply his growing automotive empire. A century later, car groups are again looking to take greater control of their raw material supply chains in the race to electrify the global car fleet…Henk de Hoop, chief executive of battery metal consultancy SFA, said the rationale for a car company to take a stake in a large miner was unclear. “If you invest in a Rio Tinto or Anglo American, then it’s a regulated shareholder relationship so it doesn’t give you a right to 20 per cent of the nickel or other metals,” he said. Carmakers switch to direct deals with miners to power electric vehicles

A junior resource company’s place in the mining food chain is to acquire projects and make discoveries.

There’s going to be a very real and increasing trend for Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) because juniors, not majors, own the world’s future mines and juniors are the ones most adept at finding these mines. They already own, and endeavor to find more of, what the world’s major miners, automakers and battery manufacturers need.

Security of supply is paramount, if they cannot get offtake agreements by investing with the world’s miners then auto and battery manufacturers will slide down the food chain and invest directly into junior resource companies.

They will do whatever it takes to secure their future, their raw material supply chains, much like Henry Ford did.

Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act authorizes almost $400 billion for investments in energy projects and climate change, including the mining of critical minerals. When this is combined with Biden’s $1 trillion investment law, which includes incentives for sourcing dozens of minerals, and this February 27th announcement from the White House Presidential Waiver of Statutory Requirements it appears a mining boom is close at hand.

It used to be that junior mining companies would only be acquired by majors and mid-tiers. That’s no longer the case. As automakers and battery manufacturers become more desperate for battery/ electrification/ decarbonization metals we could be looking at a monumental shift in the way juniors are valued.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.