‘Deadpool’ on Lake Powell could arrive as soon as July – Richard Mills

2021.12.12

Dried-up rivers and alarmingly low reservoir levels are manifestations of climate change.

Heat, that is getting worse every year and in some parts of the world is becoming literally unbearable, is inextricably linked to droughts and fresh water loss. Here’s how it works: a lack of precipitation in the mountains from a new or prolonged drought leads to a low snowpack, lessening the annual freshet that fills up rivers, that convey fresh water into lakes and reservoirs.

If this cycle continues year after year, hydro-electric power generation is imperiled, because the reservoirs are too low, as well as nuclear power generation that depends on vast amounts of water to run water-cooled nuclear reactors. This leads to blackouts, when residents and businesses who are running their air-conditioning full tilt to get some relief from the scorching heat, find the grid is overwhelmed. In future, there simply won’t be enough water to supply the amount of electricity required.

Meanwhile, our global food supply, already in jeopardy due to the war in Ukraine, and drought conditions in many parts of the world, is likely to become even more tenuous.

Heat waves, which are expected to become more frequent and more intense, could cause up to 10 times more crop damage than is currently projected. The United States experienced about $12 billion in crop losses last year, of which 82% was due to drought and wildfires.

The remarkably small global resource of fresh water — only 0.007% of water is available for drinking, feeding or fueling — is in serious peril due to climate change, increased demand and polluted water supplies.

According to the UN, demand for water is expected to grow 55% by 2050, with most of the need (70%) driven by irrigation, to feed the expanding global population, expected to hit 10 billion by 2050. Water for energy use is forecast to rise by 20%.

The supply won’t be enough to satisfy everyone. By 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in areas where water is scarce, and two-thirds will be residents in water-stressed regions, reports National Geographic. Read more

Between extreme heat and a lack of fresh water, areas of planet Earth may soon become inhabitable, putting an even greater strain on existing finite natural resources, and increasing competition for them.

Doomsday scenario for Colorado River

In April Lake Mead, America’s largest manmade reservoir, and a source of water for millions, fell to an unprecedented low. Mead has been shrinking amid a 23-year mega-drought (it’s actually the worst drought in 1,200 years) in the southwestern United States.

The graph below shows how low Lake Mead’s water level has dropped compared to 2020 and 2021.

Missing persons cases re-opened after human remains surfaced in the receding Lake Mead reservoir on five separate occasions — along with a sunken World War II-era boat and schools of dead fish.

Authorities in Las Vegas reportedly identified bones found along part of Lake Mead’s newly exposed shoreline as the remain of a 42-year-old man who drowned 20 years ago.

Hunger stones, wrecks and bones

An even more frightening scenario is developing at Lake Powell, a reservoir along the Colorado River that is a quarter of its former size.

According to a recent story in The Washington Post, if the lake drops another 38 feet, the surface would be approaching the tops of eight underwater openings that allow river water to pass through the [Glen Canyon] hydroelectric dam…

If that happens, the massive turbines that generate electricity for 4.5 million people would have to shut down — after nearly 60 years of use — or risk destruction from air bubbles.

The federal government is predicting the minimum water level for generating power could occur as soon as July, 2023. An even worse possibility, the dreaded “deadpool”, would happen if the lake level falls so low, that only small amount of water pass through the dam.

According to The Post,

Reservoirs and groundwater supplies across the region have fallen dramatically, and states and cities have faced restrictions on water use amid dwindling supplies. The Colorado River, which serves roughly 1 in 10 Americans, is the region’s most important waterway…

This year, the Biden administration called on the seven states of the Colorado River basin to cut water consumption by 2 to 4 million acre-feet — up to a third of the river’s annual average flow — to protect power generation and avoid such dire outcomes. But negotiations have not produced an agreement…

With Lake Powell at one-quarter full, [the Bureau of] Reclamation has begun a feasibility study on the prospect of harnessing the deeper bypass tubes for power generation…

Being forced to switch to the four smaller bypass tubes would instantly cut the dam’s capacity to release water by two-thirds. If water levels and pressure fell further, these pipes would quickly lose the ability to deliver the millions of acre-feet of water the lower basin states consume each year, the Glen Canyon Institute wrote in a report in August on low water scenarios.

Receding water levels are already impeding the ability of the Glen Canyon Dam to produce power; the dam currently generates about 40% less power than what has been committed to customers. What power the dam fails to generate, its customers have to buy on the open market. The cost differential is huge. The standard rate at Glen Canyon is $30 per megawatt hour, but customers last summer faced prices as high as $1,000/Mwh.

The dam is also important because it’s what is known as a “black start” facility for the country’s largest nuclear plant, the Palo Verde Generating Station in Arizona. If the plant shuts down and needs to restart, the dam could provide power to bring it back online.

According to The Post, In September, Glen Canyon sent about 80 megawatts of power to California for three hours at the height of its record-breaking heat wave, helping the state narrowly avoid rolling blackouts. It was the second time in the past few years that the dam has been called on to ramp up during emergencies threatening the electric grid, said Adam Arellano, an executive with the Western Area Power Administration.

John Fogerty – A Hundred and Ten in the Shade

Yet this ability is threatened by a hotter and drier climate. A researcher at the University of Washington reported in June that nuclear and other power plants will see a 4 to 16% drop in production between 2031 and 2060 due to climate change-induced drought and heat.

A Stanford researcher found there had been eight times the number of heat-related nuclear power plant outages in the 2010s compared with the 1990s.

When a region experiences a heat wave, water temperatures increase, accelerated by dropping water levels in lakes and rivers. Eventually the water becomes too warm to cool the reactors, without expelling water downstream that’s so hot it can damage or even extinguish aquatic life. The nuclear power plant is therefore forced to shut down.

Warming waters have induced production cuts on the Tennessee River and in coastal seas where many more plants are sited.

The phenomenon is happening not only in the United States but France, which is highly dependent on nuclear power.

In July, Wired reported that hot weather in Western Europe warmed the Rhone River to the point where it became too warm for cooling operations, leading Electricite de France to power down some reactors along the Rhone and a second major river in the south, the Garonne. Similar shutdowns occurred in 2018 and 2019. This past summer’s cuts, combined with malfunctions and maintenance, reduced France’s nuclear output by nearly 50%.

Another negative impact of warming waters is its effects on fish. With Lake Powell diminished, water temperatures have climbed so high, and dissolved oxygen levels fallen so low, that it is beginning to harm rainbow trout. Warming waters have helped recovery populations of the endangered humpback chub, but the chub are threatened by the smallmouth bass, an invasive species.

Of course, the other environmental threat to nuclear plants is flooding, as the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear power complex showed.

According to Wired,

After the Fukushima disaster in Japan, caused by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) began drafting new rules to harden existing plants to climate threats, such as storms and sea level rise. The process identified dozens of facilities that could face flooding problems under extreme conditions. But in 2019 those plans were largely scuttled by the Republican-led leadership, who argued the costs were too high for the nuclear industry to adopt for such low-probability events…

The nuclear industry and environmental groups continue to disagree on whether existing regulations capture the latest science, particularly on the topic of sea level rise.

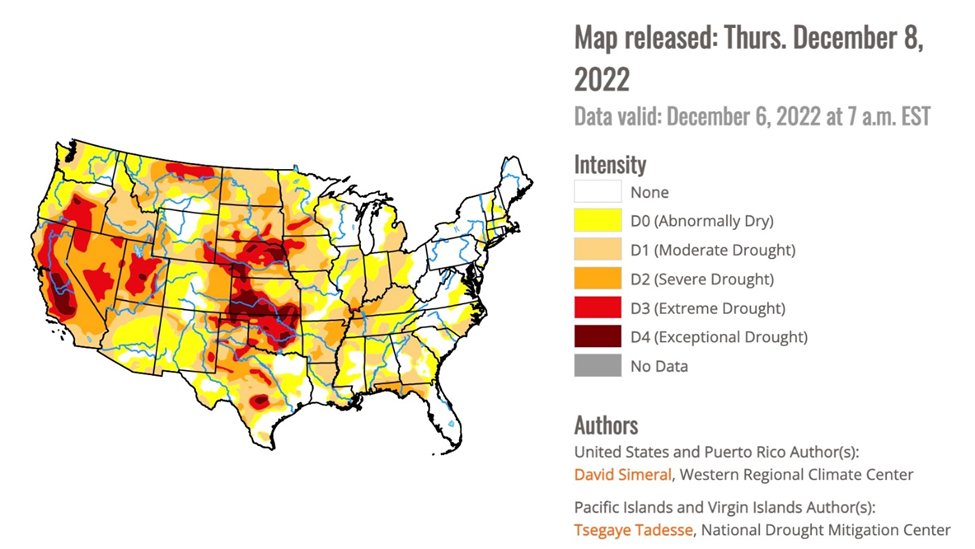

US drought continues

This year in western Canada and the US has been unusual due to the warm weather that lingered well into October, extending the forest fire season as well as late-summer drought conditions.

A story in Newsweek said in the week of Oct. 12-18, nearly 50% of the United States and 59.4% of the lower 48 states were in drought, affecting nearly 135 million people.

Some parts of the US may face continued dry conditions throughout this winter amid the La Nina weather pattern. La Nina typically takes place once every three to five years, but in 2022 La Nina occurred for the third consecutive year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

An NOAA report on Oct. 20 said “parts of the Western U.S. and southern Great Plains will continue to be the hardest hit [by drought] this winter.”

This includes California, which has suffered through its driest three-year period on record. On Dec. 1, Bloomberg reported that California cities will get limited water supplies from the state next year. Despite a series of November storms, officials are warning of another year of below-average rain and snow:

Water agencies that supply 27 million people in the most populous US state will receive 5% of what they requested in 2023, according to an initial estimate from the California Department of Water Resources.

Along with low lake levels on Mead and Powell, the ongoing dry conditions have caused record water-level lows in places along the Mississippi River in October, according to National Weather Service data. In Memphis, Tennessee, the river fell 10.75 feet, the lowest ever recorded in the city.

In western Canada, a late-summer drought prompted a state of emergency in one southern British Columbia region, caused poor crop yields in the northeastern part of the province, and had BC’s energy regulator rationing the water supply for some oil and gas companies.

According to provincial figures, via CBC News, about 80% of BC grain production occurs in the Peace region of northeastern BC. However, the weather became so dry there that in October, the province issued the highest drought warning, Level 5, meaning adverse impacts are almost certain to occur. Fort St. John recorded just 9.8 mm of precipitation in October, compared to 41.2 mm in October, 2020.

Another CBC story reported that the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission suspended 20 water permits for 12 energy companies that draw water from rivers and lakes in the Peace River and Liard River watersheds, used mostly for fracking natural gas wells:

“Low stream conditions are escalating concerns for impacts to fish, aquatic resources, and community supply,” said the regulator in a written directive to the energy industry.

Also this fall, the province issued a Level 4 drought warning, meaning adverse effects are likely to happen, to three regions — Finlay Basin and Parsnip Basin in the north and on the Sunshine Coast.

The Sunshine Coast made headlines due to its reservoir almost running dry. The region north of Vancouver saw only a trace of rain between July and mid-October, when it usually records 200 mm or more. A state of emergency was declared on Oct. 18 allowing local governments to restrict water usage. While the state of emergency has been lifted, water restrictions remain, meaning the use of water for purposes including watering lawns and sports fields, washing vehicles or filling hot tubs is not permitted.

An article that surprised me was this one by The Weather Network, on Dec. 7, saying the South Coast of British Columbia will be the “most unusually dry spot” in North America, despite La Nina.

The story notes it’s been six months since Vancouver has recorded a month with above-average precipitation. The meterological reason for the arid conditions? The polar jet stream that normally brings stormy weather to the South Coast hasn’t happened this year. Instead, it has moved over Alaska, keeping southern BC unusually dry.

And while the ongoing La Nina weather pattern (recall it’s the third year in a row) would normally favor wetter weather, the current plan is bucking that trend. The Weather Network explains:

This year, sea surface temperatures across the North Pacific have warmed with significant high pressure over the region, while the ridge has moved closer to the coast. These two factors forced most of the region’s storms to arrive from the moisture-starved northwest rather than tapping into rich moisture from the south.

Looking at the long range pattern, the most anomalously dry place in North America is the coast of British Columbia.

While Vancouver normally gets 170 mm of precipitation in December, Weather Network meteorologists say the city likely won’t get half as much. Government data shows some local water and snowpack conditions on Vancouver Island at just 25% of normal, with the provincial average snowpack at just slightly above normal. However, river flows the are the lowest on record for early December.

Food production

Besides lowering water levels in reservoirs, and warming water temperatures so much that the cooling function of nuclear power plants is imperiled, droughts also have an extremely negative impact on food production.

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

A 2021 study showed more than a fifth of global food output growth has been lost to climate change since the 1960s, putting an estimated 34 million people on the brink of famine.

Food production in the United States, like all of the world’s agricultural regions, is weather-dependent, but last year’s natural disasters were particularly impactful.

Total crop and rangeland losses were pegged at over $12.5 billion, of which drought and wildfires alone accounted for over $3.3B in losses that were not covered by Risk Management Agency (RMA) programs. Crop loss estimates from the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) do not include infrastructure damage, livestock losses, or losses to horticulture and timber.

A September article in Wired has theNational Drought Group of the UK predicting that yields of some vegetable crops—carrots, onion, and potatoes—could be cut in half. The European Drought Observatory says that almost half of the bloc is drier than it has been since the Renaissance. China’s agricultural ministry has urged farmers to undertake emergency switches to different crops following a historic heatwave.

A big part of the problem is that there are longer periods of dryness occurring before the next rain event occurs. When the rain does come, it is more often heavy, and ends up running off the land surface rather than being absorbed by it, because the soil is hard and dry.

Wired notes that in some parts of the world, droughts have already lasted long enough to profoundly disrupt food production, naming the Horn of Africa as an example:

The four most recent rainy seasons all failed. The latest one, which should have ended last May, was the driest on record. A third of the area’s livestock have died. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network, a project of the US Agency for International Development plus international nonprofits, estimates that as many as 20 million people are hungry.

In the past, governments in other parts of the world sent food aid. This year, thanks to droughts and supply shocks, that response isn’t arriving at the usual volume or speed… In normal cases, we can move food from one region to another to make up for losses… “The problem is that right now we have so many overlapping crises that the backup system is under an immense amount of stress.”

Argentina, meanwhile, is currently suffering its worst drought in decades. In the country’s Pampas farm belt, browning wheat plants are less than half as high as they should be due to a lack of water in the soil, and because of the paucity of the crop, much is likely to end up as animal feed rather than sold into the human food chain.

The country is the world’s top exporter of processed soy oil and meal, and number three for corn, but the drought has led to sharp cuts to the country’s wheat harvest forecast, and threatens to derail corn and soy too. (Reuters, Dec. 9, 2022)

Conclusion

A prolonged drought since 2000 in the Colorado River Basin (a study shows 2000-18 was the driest period in the US Southwest since the late 1500s) — which includes bits of seven western states and a part of Mexico — has made it impossible for the country’s biggest reservoirs, Lake Mead in Nevada and Lake Powell straddling the border of Utah and Arizona — to recharge fully.

This is a huge problem, considering that the Colorado River provides water for more than 40 million people including major US cities Las Vegas and Los Angeles.

Drought is also becoming prevalent in the Horn of Africa, China, Europe, Argentina, and even in British Columbia — known for its fast-flowing rivers and plentiful fresh water. Northeastern and part of southwestern BC are still showing Level 4 drought levels well into December, when they should be getting buckets of rain.

Drought affects not only the amount of water available for drinking and irrigation, but energy production (hydroelectric, nuclear, oil and gas/ fracking) and farming.

Higher temperatures, water scarcity, droughts, floods, and greater CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, all have negative impacts on the yield of staple crops.

Since the 1990s, the number of weather-related disasters around the world has doubled, a pattern that greatly increased the risk of food insecurity and food prices. Sadly, this trend is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.