Commodities are the trade for riding out the Fed-caused recession – Richard Mills

2022.09.22

At the Federal Reserve’s annual retreat in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Chairman Jerome Powell decided to scrap his original address and instead delivered unusually blunt remarks: the Fed would accept a recession as the price of fighting inflation.

As the Wall Street Journal describes it,

Mr. Powell cited the example of former Fed chairman Paul Volcker, who drove the economy into a deep hole in the early 1980s with punishing rate increases to break the back of double-digit price gains. “We must keep at it until the job is done,” Mr. Powell said, invoking the title of Mr. Volcker’s 2018 autobiography, “Keeping At It.”

The moment underscores the Fed chairman’s rapid about-face during one of the most tumultuous periods for the economy and central bank since the 1970s. After championing an aggressive stimulus campaign just 12 months ago, he has this year led the most rapid tightening of monetary policy since the early 1980s.

The upshot is that Fed officials could keep raising rates until they force unemployment higher and slow wage growth. It’s the clearest signal yet that the central bank’s intention is to “go hostile”, that the only way it is able to fight the 8.3% level of inflation that has permeated the economy, is to “crash the markets”. That is precisely what Paul Volcker’s Fed did in the early 1980s.

History tells us that previous Fed rate hikes to deal with uncomfortably high inflation resulted in recessions.

During the 1970s consumer price inflation averaged 7%. To tackle it, then-Fed chair Paul Volcker dramatically raised interest rates. From 11.2% in 1979, Volcker and his board of governors through a series of rate hikes increased the federal funds rate to 20% in June 1981. This led to a rise in the prime rate to 21.5%, which was the tipping point for the recession to follow, lasting two years.

Goldman Sachs says the main goal of the Fed’s rate hikes — an astounding five so far this year including Wednesday’s +0.75%, bringing the federal funds rate to 3.25% — is to slow wage growth from 5-6% to 4-5%, helping cool inflation close to the Fed’s 2% target in 2023-24.

Wages and salaries for private-sector workers rose 5.7% for the 12 months through June.

The other important objective is to crush demand, including tempering consumer spending, which makes up about 70% of the economy, by making it more expensive for individuals and businesses to borrow.

Remember, the Fed has two responsibilities: to allow the economy to grow at a rate no faster than 2% inflation, by calibrating interest rates; and to ensure that the economy is running at or near full employment. The central bank therefore keeps a close eye on inflation and unemployment figures.

One Fed official, quoted by the Wall Street Journal, suggested that the central bank would be comfortable with the jobless rate rising to around 5% from its current 3.7% — a magnitude that has never occurred outside a recession.

In an article titled “Is A Bear Market Lurking”, author Lance Roberts references the stock market to explain why the Fed nearly always “breaks the market” when raising interest rates.

Consider: stock valuations in 1929, 2000 and 2008 were abnormally high, just prior to each recession. Think of the crash as a blunt instrument that pounds valuations back into line. “Historically, the Federal Reserve hikes rates until ‘something breaks,’ which resolves the overvaluation problem (i.e., prices fall sharply),” Roberts writes.

It’s easy to see how this leads into a recession. Corporate earnings remain elevated heading into a tightening campaign, but higher interest rates and surging input costs (inflation) put earnings at risk.

The latest (August) inflation readings showed the Consumer Price Index (CPI) running at +8.3% and the core CPI — growth of prices excluding food and energy — hitting 0.6% in August, double July’s pace.

A recession is what results when an economy stops growing. Economists define it as two consecutive business quarters of decline in GDP, which is the total value of all goods and services a country produces. Technically the United States is already there, with US second-quarter GDP falling by 0.9%, and Q1 GDP declining by 1.6%.

The markets have heard Powell’s message of higher interest rates, and the damage they could cause the greater economy, loud and clear.

The S&P 500 has slid 8.4% over the past month (as of the close of trading Wednesday), and the 2-year Treasury yield recently hit its highest level since 2007.

Dr Doom: Recession will be “severe, long and ugly”

How bad could it get? The economist who predicted the financial crisis sees a “long and ugly” recession happening at the end of this year, including a sharp correction in the S&P 500, that could last all of 2023.

“Even in a plain vanilla recession, the S&P 500 can fall by 30%,” says Nouriel Roubini, quoted by Bloomberg in an interview, Monday. In “a real hard landing,” which he expects, it could fall 40%.

Roubini, nicknamed “Dr. Doom” for correctly anticipating the housing crash of 2007-08, pointed to the large debt ratios of corporations and governments as particularly concerning, a development we addressed in an article titled ‘1979 vs 2022: Why interest rate hikes are different’.

This is due to the fact that as rates rise, debt servicing costs increase.

“Many zombie institutions, zombie households, corporates, banks, shadow banks and zombie countries are going to die,” he said. “So we’ll see who’s swimming naked.”

In 2020 global debt experienced the largest surge in 50 years.

According to the FRED chart below, the US debt to GDP ratio was around 35% during the 1982 recession. Today it is more than three times higher, at 124%.

This limits how much and how quickly the Fed can raise interest rates, due to the amount of interest that the federal government is forced to pay on its debt.

While some market observers believe the Fed will pivot to lowering interest rates, and restarting quantitative easing (QE), once the world is in recession, Roubini isn’t one of them.

He doesn’t expect fiscal stimulus remedies because governments are “running out of fiscal bullets,” and high inflation means that “if you do fiscal stimulus, you’re overheating the aggregate demand.” Roubini therefore sees stagflation like in the 1970s, and debt distress like in the global financial crisis.

“It’s not going to be a short and shallow recession, it’s going to be severe, long and ugly,” he said via Bloomberg, adding that his advice to investors is “to be light on equities and have more cash.”

In April Sunshine Profits presciently wrote:

The US economy is likely to shift from an economic recovery to stagflation in the upcoming months. Even the Fed itself admits that inflation will jump this year. Of course, the central banks are trying to convince us that inflation will be only transitory, but it’s possible that they underestimate the inflationary risk and overestimate their ability to deal with it.

In fact this is precisely where we are now. The World Bank admits that the risk of stagflation is heightening, stating in its latest report, ‘Global Economic Prospects’, that “stagflation risks are rising amid a sharp slowdown in growth.” The institution reduced its global growth forecast from 5.7% in 2021 to 2.9% in 2022, significantly lower than the 4.1 % predicted in January. Furthermore, the World Bank projects world GDP will slow by 2.7 percentage points between 2021 and 2024 — more than twice the deceleration between 1976 and ’79.

The Buffett Indicator

When markets swoon, many stockholders turn to Warren Buffett for investment advice. The “Buffett Indicator” is a valuation measure that compares the stock market’s capitalization to the Gross Domestic Product. The indicator currently sits at 2.44.

The chart below by Real Investment Advice plots the business cycle going back to 1951, with recessions marked as vertical grey lines. Notice that, just before a market crash, the Buffett Indicator, shown as an orange line, spikes. We see this in 1973 (1.29), just before the crash of 1974; in 1999 (2.11), the year prior to the dot-com crash; 1.52 in 2007, leading up to the financial crisis, and 2.71 in 2019, just prior to the coronavirus crisis that began in early 2020.

According to Real Investment Advice, the current Buffett Indicator ratio of 2.44 show that, Even after the recent fall in markets, the ratio is still one of the highest on record, north of the 2.11 level recorded during the dot-com bubble of 2000, and considerably elevated compared to the average since 1950.

The Buffett Indicator tells us that overvaluation is unsustainable when the market capitalization of stocks grows faster than what economic growth can support. Any number above 1.0 is overvalued, and below 1.0 is undervalued. Investors currently are paying almost 2.5X what the economy can generate in revenue and earnings.

Can the model tell us when we should sell all our equities and go to cash? Unfortunately, no. But it does give a reasonable expectation of future market returns. According to Real Investment Advice:

Stocks are far from cheap. Based on Buffett’s preferred valuation model and historical data, return expectations for the next ten years are as likely to be negative as they were for the ten years following the late ’90s.

Undervalued commodities

Yikes. With the Buffett Indicator pointing to a “lost decade” of negative returns, and Nouriel Roubini predicting the recession will be “severe, long and ugly,” the obvious question is how to batten down the hatches and survive the coming storm. The answer, commodities, may surprise you. It certainly surprised me.

Commodities protect investments from rising prices and currency debasement, making them a good place to park your hard-earned cash. However, both the energy and materials sectors are considered very economically sensitive, exemplified by oil and copper pulling back from their (respective) June and March highs.

The thing to remember, is when investing in natural resource equities, the commodity capital cycle is more important than the business cycle.

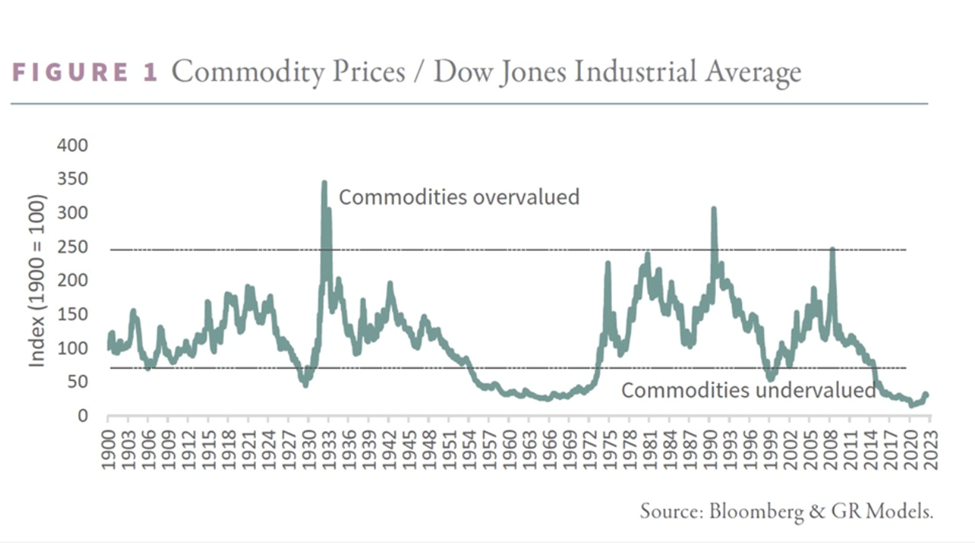

I found the chart below in a recent report from Goehring & Rozencwajg, the Wall Street natural resource investment firm.

The chart shows the relationship between the Dow Jones Industrial Average and a commodity index going back several decades. It indicates periods when commodities are undervalued or overvalued — compared to the Dow. Where the green line dips below 75, commodities are cheap relative to financial assets. These periods typically represent bear markets for commodities. The chart shows the most undervalued years for commodities were 1929, 1969, 1999 and 2020.

What makes commodities cheap, relative to financial assets? According to G&R, it has to do with natural resource capital spending:

A commodity price cycle usually follows a typical path. The industry might enjoy a period of very high energy or metal prices. Given their fixed cost base, the higher commodity prices fall directly to the bottom line resulting in a period of super-normal profits. High returns attract new capital and before long the industry begins a new cycle of exploration and development. Over time, increased spending leads to new supply which eventually outpaces demand growth and ushers in a period of commodity surplus. Prices fall, causing projects that were underwritten at higher prices to become impaired and written off. Often, another industry or investment strategy falls into favor around this time and investors rush to reallocate capital towards hot new speculative areas, leaving the resource industry even more capital starved. As depletion takes hold, supply falters, demand grows, and inventory gluts eventually get worked off. The stage is set for the next bullish cycle to start.

G&R’s advice is to buy resource stocks when commodities are cheap, and during bottoms in the natural resource capital investment cycle.

The key point is that even if we were to go into another recession, it doesn’t mean that commodity prices will fall in lockstep, as they did in 2008. In fact, they (and resource equities) are likely to hold their own and do quite well, because unlike in 2008, commodities are undervalued, shown on the chart as the green line below 75. (in 2008 the Commodity Prices/ Dow Jones Industrial Average was about 300, well into the “Commodities overvalued” range).

In terms of G&R’s commodity capital cycle described above, we are currently in the stage of depletion, when supply falters, demand grows, and inventory gluts get worked off. The stage is, imo, set for the next bullish cycle to start.

In their report, G&R maintain that The radical undervaluation of commodities and commodity related equities is greater now than it was back in 1929, and the level of capital starvation is just as great. History tells us that commodities could again be an excellent place to seek high returns, even if the 2020s experience a period of economic turmoil as severe as the Great Depression — a scenario we consider unlikely.

Conclusion

G&R’s Commodity Prices/ Dow Jones Industrial Average chart shows there hasn’t been a better setup for commodities than now, over a time frame spanning 120 years.

There are many reasons to be bullish on commodities and, a lot to indicate that inflation is not going away anytime soon, thus setting up the conditions for a multi-year commodities up-trend.

First, there has been a lack of spending on exploration and development, leading to current and looming supply shortages for a number of metals. The mining companies in the mid-2010s basically ate each other and by shutting down exploration there was no accretive increase in reserves. Lower ore grades have also become an issue.

Second, natural resources are being used up faster than they can be replenished; this is another theme driving commodity prices higher.

Third, countries that have the metals needed to fuel economic growth are guarding them more closely than previously; resource nationalism is on the rise.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates this transition will require about $173 trillion in investments over the next 30 years.

We are looking at elevated prices for certain critical and industrial metals that are central to the new green economy, like copper, lithium and graphite, for years if not decades to come.

Simultaneous and dramatic price increases for energy and food are part of a ballooning cost-of-living crisis in much of the developed world, as inflation continues to wrack economies and central banks try to control it through interest rate increases that are impeding growth, and threaten to plunge the global economy into a deep recession.

Despite the recent lowering of gas prices and some grocery items, the problem of dual-track energy and food inflation is anything but solved.

The bottom line? Even if the recession is long, commodities should be practically bullet-proof.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Follow me on Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.