Why metals, energy and food prices will remain elevated

2022.05.31

With inflation in the US reaching its highest in 40 years, there is no better time to go “all in” on commodities, a well-known hedge against rising prices. Those who have already done so have fared quite well.

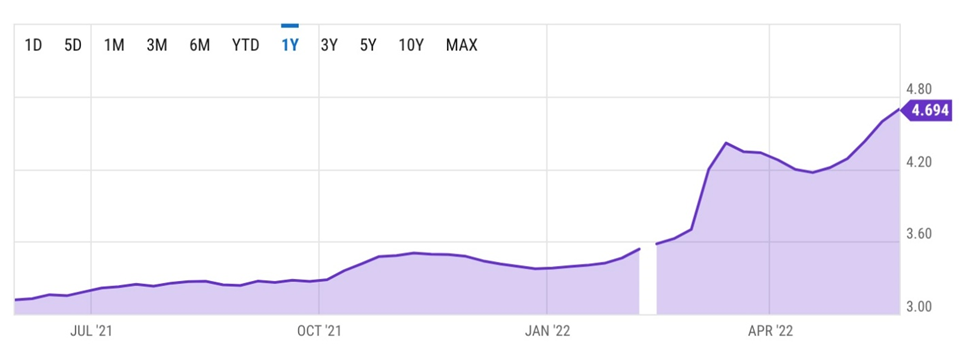

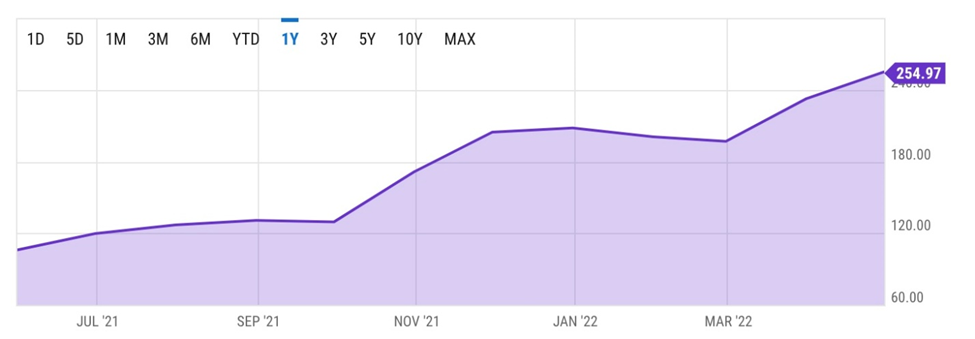

The Bloomberg Spot Index (BCOMSP), which tracks 23 energy, metals and crop futures and is considered a good barometer of the sector, has gone up by 38% over the past 12 months! No other traditional asset class comes close to matching this kind of return.

The good news is the party has only just gotten started for investors. In 2022, commodities are going bonkers as inflationary pressures continue to pile up, with no signs of easing. The BCOMSP is already up by 30%, five months into the year.

Analysts including Goldman Sachs’ global head of commodities research Jeff Currie have repeatedly stated that we are bearing witness to the beginning of a decade-long “commodity supercycle”. In this article we explain why metals, oil & gas and food, whose prices have all increased significantly following the invasion of Ukraine in February, will in our opinion continue to out-perform the broader market.

Demand drivers

The new supercycle being touted by Goldman Sachs and others is tied to the infrastructure deficits that many countries need to reduce.

In many countries, basic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water & sewer systems, have all been poorly maintained, and require hefty investments — measured in trillions of dollars — to repair or replace.

China, the world’s biggest consumer, has committed to spending at least 14.8 trillion yuan (US$2.3 trillion) this year on thousands of “major projects”, according to Bloomberg reports. They are part of Beijing’s most recent Five-Year Plan that calls for developing “core technologies” including high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy.

The United States is pursuing its own trillion-dollar infrastructure package, to be spent on roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, among many other items.

For such plans to work, extensive minerals are needed to build the required infrastructure, and will have to compete with one another (plus every other country) to do so, driving commodity prices higher.

It’s no wonder that analysts are now so bullish on commodities.

An extension of the infrastructure buildout is the global transition towards a “green economy”, which can only be accomplished with renewable power, electric vehicles and energy storage technologies.

All of these require lots of minerals. The amount of raw materials we’ll need to extract from the Earth to feed this transition is staggering.

According to BloombergNEF, it would take 10,252 tons of aluminum, 3,380 tons of polysilicon and 18.5 tons of silver to manufacture solar panels with 1GW [gigawatt] capacity.

Wind turbines need steel, copper, aluminum, nickel and other materials. To construct wind turbines and infrastructure with the power capacity of one gigawatt, BNEF found that 154,352 tons of steel, 2,866 tons of copper and 387 tons of aluminum are needed.

For lithium-ion batteries, the key metals are copper, aluminum, lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese. BNEF estimates that it would take 1,731 tons of copper, 1,202 tons of aluminum, and 729 tons of lithium to manufacture 1GWh batteries.

All in all, BNEF estimates that the global transition will require about $173 trillion in investments over the next three decades; until then, every commodity under the sun will be gobbled up.

One of the most important things to understand about energy and metals demand, is the redirection of capital that has occurred over the past five years due in part to poor returns. Companies stopped putting money into old-world economic sectors like oil, coal and mining, and instead plowed funds into renewable energies and ESG (environmental, social and governance) funds. As a result, a demand imbalance has been exposed, that needs to be corrected if there is to be a smooth transition from dirty to clean energy. Goldman’s Jeff Currie explains:

“The problem is the best fuel for that is gas to deal with the intermittency problem of when the wind is not blowing, and the sun is not shining. Now the problem with gas is it is an old economy hydrocarbon-based fuel.”

Indeed the environmental effects of natural gas are nasty due to the means in which it is often extracted — fracking. Yet that hasn’t stopped the demand for it, and prices, from pushing higher due to fallout from the Russia-Ukraine war.

On Wednesday, May 25, US benchmark NG prices hit $9 per million British thermal units (MMbtu) for the first time since 2008, fueled by record LNG exports and unseasonably high demand for electricity. Prices have surged 130% so far this year, due to strong demand for LNG in Europe, which is scrambling to replace Russian gas the continent relies on for 40% of its gas supply, Oilprice.com reported. Early heat waves in the US that began at the start of May have also boosted demand for air conditioning and power generation.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects the Henry Hub price to average $7.83/MMBtu in the second quarter and $8.59/MMBtu in the second half. High forecast natural gas prices reflect the EIA’s expectation that natural gas storage levels will remain less than the five-year (2017–2021) average this summer.

Meanwhile the US government’s strategic petroleum reserves have fallen to a 35-year low of 538 million barrels, resulting from the Biden administration’s decision earlier this year to sell up to 189M barrels within six months. The release is the largest since the reserve was created in 1974, and is being done, mostly unsuccessfully, to try and curb high gasoline prices ahead of the mid-term elections in November.

“What remains true across global markets is that inventories are low, particularly for products,” Schneider Electric’s Robbie Fraser told Seeking Alpha, a challenge that is “likely to persist as northern hemisphere summer travel demand is poised for a boost to gasoline, diesel and jet fuel demand over the weeks and months ahead.”

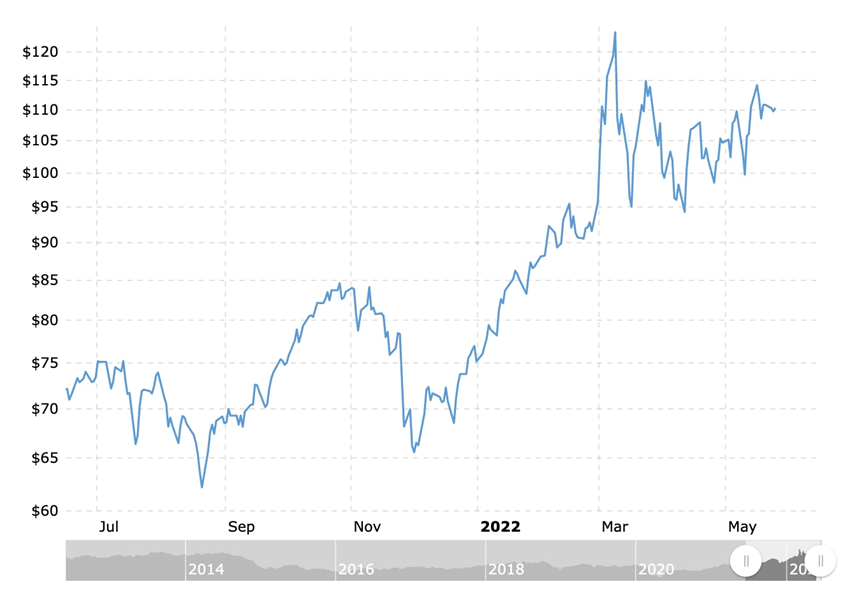

WTI, the US crude oil benchmark, has climbed 45% since the beginning of the year, including a 13-year high of $130/barrel reached on Mach 6 following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Oilprice.com sees the oil bull market continuing due to a number of factors, including an easing of Chinese lockdown rules that is rekindling hopes of stronger East Asian buying over the summer; the prospect of the European Union formalizing an agreement on Russian oil sanctions; Libya back on the brink of civil war; OPEC+ underproducing; and West Africa continuing to struggle with supply disruptions.

Power crisis looming

Tightness in the oil and gas markets is spilling over into the power sector. A “perfect storm” of factors threatens much of the northern hemisphere, with rolling blackouts predicted this summer due to grids stretched thin by fossil fuel shortages (not only oil and gas but coal), droughts and heat waves, covid-related logistical problems, soaring prices from the war in Ukraine, and the failed green energy transition where too many gas and nuclear plants were retired too soon.

Zero Hedge reports the power crisis affecting much of the world including some of the top economies, could be less than a month away, when summer officially begins on June 21.

Supply drivers

Referring again to the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index, which hit a new record earlier this year, driven in part by surging oil prices, Goldman Sach’s Jeff Currie said he’s never seen commodity markets pricing in the shortages they are right now.

“I’ve been doing this 30 years and I’ve never seen markets like this,” the commodity expert said in a Bloomberg TV interview. This is a molecule crisis. We’re out of everything, I don’t care if it’s oil, gas, coal, copper, aluminum, you name it we’re out of it.”

Lingering supply chain issues from covid and the war in Ukraine have made these pressures even stronger.

Nickel prices spiked following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, a major supplier of the base metal through state-owned miner Norilsk.

Copper is seeing its cupboard dry up, from a dearth of new discoveries and lack of capital spending on mine development in recent years. Analytics firm S&P Global predicts that due to a shortage of projects, copper supply will lag demand as soon as 2025.

In 20 years, BloombergNEF says copper miners need to double the amount of global copper production, just to meet the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles — from the current 20Mt a year to 40Mt.

Remember, copper is already one of the most consumed industrial metals on the planet, and the bellwether for the global economy. The commodity will always be in great demand, and the threat of a decades-long supply shortage should keep its price elevated.

Another commodity in the spotlight is lithium, the key ingredient in electric vehicle batteries.

S&P Global forecasts that this year, further demand growth could push the lithium market towards a deficit as increased use of the material outstrips production and depletes stockpiles.

Supply of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) is forecast to jump to 636,000 tonnes in 2022, up from an estimated 497,000 in 2021 — but demand will move even higher to 641,000 tonnes, from an estimated 504,000, S&P said in its December 2021 report.

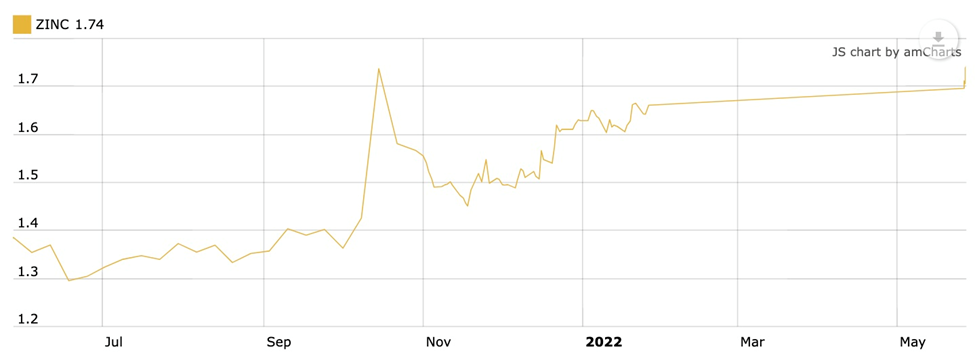

Metals such as nickel, cobalt, graphite and zinc, are also surging, on supply concerns.

Zinc reportedly moved from a 5.3 million tonne surplus in 2020 to a million-tonne deficit in 2021, with warehoused metal in London and Shanghai recently plummeting to six days consumption.

The fourth most used metal in the world is likely to stay at multi-year highs in 2022 owing to high energy costs resulting from the war in Ukraine. Spot zinc is up 25% over the past year, and Fitch Solutions has raised its 2022 price target to $3,500 a tonne from $2,900/t. At this rate, zinc is on track to reaching its all-time high of $2.06/lb, in November 2006.

Echoing what Goldman’s Jeff Currie and others are saying about a new commodity supercycle focused on the green economy, Eurasian Resources’ CEO Benedikt Sobotka believes that commodities right now are in a “perfect storm”.

Sobotka told Reuters the fossil fuel resurgence is temporary and the transition to a lower-carbon can’t be stopped. Meeting the demand for clean energy and transportation will require an eye-watering $50 trillion over the next three decades, or an investment of $200-300 billion per year. He predicts the majority of funds will go into the mining of copper, nickel, cobalt and other “green” metals, and forecasts a 20% rise in copper prices by the end of this year.

In the same way that the oil and gas industry has been starved of investment dollars, in favor of trendy renewable power projects, Sobotka notes that “Years of under-investment in mining of metals essential to energy transition, supply shocks and high energy prices will continue to drive commodity prices higher.”

He therefore expects companies and countries to stockpile strategic raw materials including oil, copper and cobalt, and notes that major end users such as the auto industry are already signing offtake agreements. There are many examples.

In 2020 Tesla signed a contract with Vale-NC to supply intermediate mixed nickel and refined cobalt produced in New Caledonia.

Earlier this month, company representatives flew to Indonesia to visit Morowali, the nickel production center on Sulawesi Island. This was followed by a visit from Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo to Tesla’s Gigafactory in Texas, to meet with Elon Musk. Major battery makers LG Energy and CATL have both signed multi-billion dollar deals to manufacture batteries in Indonesia, the world’s no. 1 nickel supplier.

According to a recent Bloomberg story, Gotion High-tech Co., a lithium-ion battery producer, is looking at cooperating with Argentina’s state-owned miners Jujuy Energia, to build a lithium carbonate refinery there. In Zimbabwe, Chengxin Lithium Group and Sinomine Resource Group are joint venturing to explore for lithium, while Chinese mining giant Tianqi Lithium is teaming up with battery maker CALB.

Resource nationalism

Widespread metal supply shortages are being made worse by resource nationalism — the tendency of governments to localize the mining industry and to increase the extraction costs to foreign miners.

With much of the “low-hanging fruit” already picked, there is a need to go further afield and dig deeper to find metals at the grades needed to mine them economically. This usually means riskier jurisdictions that are often ruled by shaky governments, with an itchy trigger finger on the resource nationalism button. Recent examples include Chile, Peru, Indonesia, and even the United States.

The Biden administration has made a number of anti-mining decisions, with the latest being the imposition of new pollution restrictions on the massive Pebble project in Alaska. Under the proposed requirements, the EPA would ban mine developer Northern Dynasty from disposing waste near the site due to potential harm to the area’s salmon fishery, effectively thwarting the long-stalled project.

Food supply crunch

Turning to agricultural commodities, the repercussions of Russia’s war with Ukraine have certainly been felt by consumers, as supply chain disruptions and economic sanctions have made food more expensive.

Historically, Ukraine is known as the “breadbasket of Europe”, given that it has some of the most fertile soil in the world. About 25% of global wheat exports are through Ukraine, and it is the number one maker of sunflower oil. Russia is a major producer of agricultural products, as well as a top exporter of nitrogen fertilizers.

As such, the ongoing war in Ukraine is seen as a major disruptive force in the global food market.

Food prices have soared since the start of the year, with the FAO Food Price Index reaching a record high in March. This was coming off a year in which prices jumped 28%, the highest in a decade.

Those hoping for a reprieve in the cost of groceries will find it unlikely to happen anytime soon.

The key input in agriculture is fertilizers, which farmers use to supplement natural soil nutrients, antibiotics to prevent animal diseases, and pesticides to protect crops against animals, insects, weeds and various microorganisms.

The cost of raw materials in the fertilizer market — ammonia, nitrogen, nitrates, phosphates, potash and sulfates — has gone up by 30% since the start of 2022.

The culprit behind the skyrocketing fertilizer and consequently food costs is the rise in energy prices.

Natural gas is used as a raw material to produce ammonia, the building block for all nitrogen fertilizers, which accounts for most of the world’s fertilizer consumption. Typically 60% to 80% of production costs are natural gas.

US natural gas prices recently hit their highest since 2008. Due to higher NG prices in Europe, various fertilizer companies have been forced to shut down, leading to supply concerns.

After touching a record-high in March, fertilizer costs haven’t shown any signs of slowing down, with all eight major fertilizers tracked by DTN seeing increases in April.

As the price of fertilizers continues to soar, so do our food products, as farmers around the world are forced to cut their fertilizer use.

A searing drought in India led the Indian government to ban wheat exports, causing global prices to jump nearly 6%. On May 15 Chicago wheat futures hit $12.47 a bushel, their highest level in two months. Wheat prices have risen more than 60% this year, driven by supply disruptions owing to the war in Ukraine. Russia and Ukraine account for nearly a third of the world’s wheat exports.

Meanwhile, conditions for US growers have been poor, with the southern plains portion of the “wheat belt” experiencing a prolonged drought. The US Agriculture Department forecasts a major decline in wheat stocks this year, saying they will fall to a 9-year low.

According to The Daily Telegraph, the world has only 10 weeks worth of wheat stockpiled, due mainly to the war limiting agricultural production in the Black Sea region, and bottlenecking shipments.

Agriculture consultancy Inform recently cut its forecast for Ukraine’s sunflower seed harvest to 9.2 million tonnes from its previous 9.6Mt outlook; production is down dramatically from the 16.6Mt in 2021.

The war has also affected the price of corn, which hit a 9-year high in April. Ukraine is the world’s fifth largest corn producer. According to CNBC, futures traders have been betting that higher input costs and more demand for corn as a substitute food item will drive up the price.

The news outlet says that even before the war, agricultural commodity markets including corn were tight due to supply chain pressures and high transportation costs, which have been contributing to US inflation.

Gro Intelligence chief executive Sara Menker called the number of “extraordinary challenges” impacting global food supplies, including fertilizer shortages, climate change, and record-low inventories of cooking oils and grains, “a once-in-a-generation occurrence that can dramatically reshape the geopolitical era.”

Conclusion

Commodities have always been influenced by the weather, climate and geopolitical events. With globalization, supply chains are easily disrupted by war. The ongoing conflict between Ukraine and Russia has resulted in an eruption in commodity prices, especially those produced by the two combatants. This includes fertilizer, wheat, corn, sunflower oil, crude oil, natural gas (Russia is the world’s largest oil exporter and a major producer of natural gas; Ukraine has a long history of producing oil and natural gas, with proven NG reserves equivalent to over 35 times its annual consumption), nickel and palladium.

But wars are temporary, and eventually the one in Ukraine will end. The longer-term trend driving energy and metal prices higher is the transition to a low-carbon economy. As mentioned, meeting the demand for clean energy and transportation will require $50 trillion over the next three decades. Among the metals most likely to benefit, are copper, ubiquitous in everything from construction to telecommunications to transportation (EVs use 4X as much copper as regular vehicles), zinc, and battery metals such as lithium, nickel, cobalt and graphite. Structural supply issues for energy-critical metals like copper, are likely to keep prices elevated for several years. The cure, of course, is finding new deposits, but this takes time, money, and forward thinking, all of which are currently lacking in policymakers.

In the same way that the oil and gas industry has been starved of investment dollars, years of under-investment in mining, particularly metals essential to the energy transition, will continue to push prices higher.

The long-term price determinant for agricultural commodities is climate change. As long as extreme heat and droughts continue to plague major breadbaskets such as the United States and India, growers will be challenged to meet their yields, especially with input costs like fertilizer, feed and diesel becoming more expensive.

We therefore see nothing stopping the prices of energy, metals and food from rising, in what we believe is only the beginning of a commodities bull market that could last for decades.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.