Russia’s war in Ukraine, seen through the lens of fossil fuels and climate change

2022.05.26

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, pundits explained it as President Vladimir Putin’s attempt to redress perceived historical injustices and to regain territory that was lost to the former Soviet Union when it collapsed in 1991.

The BBC wrote, Putin unleashed the biggest war in Europe since World War Two with the justification that modern, Western-leaning Ukraine was a constant threat and Russia could not feel “safe, develop and exist”.

The Russian leader’s initial aim was to overrun Ukraine and depose its government, ending for good its desire to join the Western defensive alliance NATO. After a month of failures, he abandoned his bid to capture the capital Kyiv and turned his ambitions to Ukraine’s east and south.

Launching the invasion on 24 February he told the Russian people his goal was to “demilitarise and de-Nazify Ukraine“. His declared aim was to protect people subjected to what he called eight years of bullying and genocide by Ukraine’s government. Another objective was soon added: ensuring Ukraine’s neutral status .

The New York Times expounds further on these themes, particularly the threat to Russia posed by NATO’s eastward expansion, when the Western military alliance took in former parts of the ex-Soviet Union and its client states, including the Baltic republics of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, Poland and Romania, among others:

As a result, NATO moved hundreds of miles closer to Moscow, directly bordering Russia. And in 2008, it stated that it planned — some day — to enroll Ukraine, though that is still seen as a far-off prospect.

Mr. Putin has described the Soviet disintegration as one of the greatest catastrophes of the 20th century that robbed Russia of its rightful place among the world’s great powers. He has spent his 22 years in power rebuilding Russia’s military and reasserting its geopolitical clout.

The Russian president calls NATO’s expansion menacing, and the prospect of Ukraine joining it a major threat. As Russia has grown more assertive and stronger militarily, his complaints about NATO have grown more strident. He has repeatedly invoked the specter of American ballistic missiles and combat forces in Ukraine, though U.S., Ukrainian and NATO officials insist there are none.

Mr. Putin has also insisted that Ukraine is fundamentally parts of Russia, culturally and historically.

East-West relations worsened drastically in early 2014, when mass protests in Ukraine forced out a president closely allied with Mr. Putin. Russia swiftly invaded and annexed Crimea, part of Ukraine. Moscow also fomented a separatist rebellion that took control of part of the Donbas region of Ukraine, in a war that still grinds on, having killed more than 13,000 people.

What does Putin want?

Mr. Putin appears intent on winding back the clock more than 30 years, establishing a broad, Russian-dominated security zone resembling the power Moscow wielded in Soviet days. Now 69 years old and possibly edging toward the twilight of his political career, he clearly wants to draw Ukraine, a nation of 44 million people, back into Russia’s sphere of influence.

Russia presented NATO and the United States in December with a set of written demands that it said were needed to ensure its security. Foremost among them are a guarantee that Ukraine would never join NATO, that NATO draw down its forces in the Eastern European countries that have already joined, and that the 2015 cease-fire in Ukraine be implemented — though Moscow and Kyiv disagree sharply on what that would mean.

The West dismissed the main demands out of hand. Moscow’s aggressive posture has also inflamed Ukrainian nationalism, with citizen militias preparing for a drawn-out guerrilla campaign in the event of a Russian occupation.

The invasion threatens to destabilize the already volatile post-Soviet region, with serious consequences for the security structure that has governed Europe since the 1990s. Mr. Putin has long lamented the loss of Ukraine and other republics when the Soviet Union broke apart. Now, diminishing NATO, the military alliance that helped keep the Soviets in check, appears to be part of his mission. Before invading, Russia made a list of far-reaching demands to reshape that structure — positions NATO and the United States rejected.

But what if there was another reason for Putin’s aggression, that being a desperate attempt to cling to an oil & gas economy that Russia both depends on and is losing rapidly to due to resource depletion and the global shift from fossil fuels to electrification/ decarbonization? In other words, the war is less about politics, strategy, culture, or prestige, than the preservation of its oil-based economy, through military might.

Invading Ukraine was also a way for Russia to gain territory to the south, with access to ice-free ports on the Black Sea, and Ukraine’s vast grain fields, during a time when Russia is increasingly on the front lines of climate change.

Permafrost problem

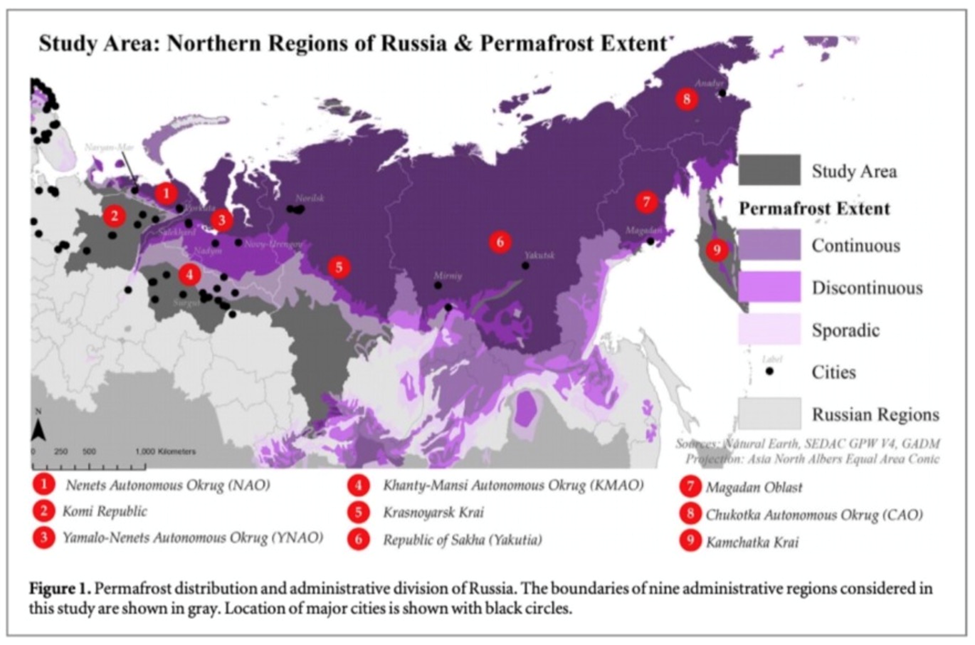

Two-thirds of the country is encased in permafrost — in some areas it’s over a kilometer deep — but warmer temperatures are thawing it. A large share of Russia’s oil, gas and metals are produced in cities that sit on permafrost. Thousands of kilometers of roads, rails and pipelines could sink into the mud, and hundreds of buildings and processing plants will fall over if the ground thaws. Russia has 24 regions that are permanently frozen and while only nine of those contain extensive infrastructure and cities, they are key to Russia’s economy, producing raw materials that account for nearly half of Russia’s GDP. (‘Russia’s permafrost is melting’)

Temperatures in northeastern Russia are rising two and a half times faster than the rest of the world. Last June Moscow was the hottest in 120 years, with the country experiencing its warmest June since 2012.

In March, Arctic weather stations were a shocking 30 degrees C hotter than seasonal averages, while in polar regions near Russia, the mercury pushed above freezing in what should be one of the coldest months of the year, The Economist reported. Recent data shows the Arctic is now warming 3-4 times faster than elsewhere, with sea ice in rapid retreat and polar ice caps shrinking.

According to climate scientists, Russia especially its Siberian and Arctic regions is among the countries most exposed to climate change. A number of records have been set in recent years including in June 2020, when the town of Verkhoyansk reached 38 degrees C, the highest temperature recorded above the Arctic Circle. Climbing mercury levels have caused devastating forest fires and floods.

In the Siberian city of Norilsk, a fuel tank collapse in 2020 spilled 21,000 tons of diesel fuel into the Ambarnaya River, polluting an 180,000-square-meter area. The leak was blamed on abnormally warm weather and thawing permafrost, which weakened the structural integrity of the tank.

The spill originated from the power plant at Norilsk Nickel, the world’s largest producer of refined nickel and palladium — forcing the company to pay $2 billion in compensation.

There are worries among the local population that with a large share of Russian oil and gas operations concentrated in the Arctic, there will be more such environmental disasters.

Last year, Norilsk Nickel had to partly suspend operations at its Oktyabrsky and Taimyrsky mines after noticing subterranean water flowing into one of them at a depth of 350 meters. Thawing permafrost was the likely culprit.

The Russian nickel and platinum group element miner reportedly had to install barriers and pour 30,000 tonnes of concrete into the underground mines in Siberia to stop the water flow. Oktyabrsky and Taimyrsky account for just over a third of the ore mined by Norilsk Nickel in Russia.

According to Politico, the ground’s ability to support buildings across the country’s frozen north will degrade by up to a third by 2050, creating an infrastructure disaster that could cost $132 billion.

The publication also notes that anthrax released from the melting soil in recent years is only the first warning shot, citing a scientific study:

In recent years particular attention has been devoted to the process of permafrost degradation and to the increasing thawing rates of the active layer. Indeed, not only do these processes produce sizable impacts on landscape degradation, ecological and hydrological systems, infrastructure stability and carbon release, which in turn is expected to increase global warming, but they may also bring to light at a fast rate contaminants (such as persistent organic pollutants, mercury and others) that were deposited and stored over the years.

The Economist recently noted that Arctic permafrost is thought to contain 1.7 trillion tonnes of carbon frozen in organic matter — an amount that is double what currently resides in the atmosphere. Rising temperatures will cause this trapped carbon to escape as carbon dioxide and methane, powerful gases known to cause the greenhouse effect. This causes a feedback loop of more melting and more greenhouse gas emissions.

A paper published in ‘Nature Reviews Earth and Environment’ warns that, should the top three meters of permafrost thaw, it could result in the release of 624 million tonnes of carbon a year by 2100.

The study’s lead author, Jan Hjort from the University of Oulu in Finland, concludes that of 120,000 buildings, 40,000 km of roads and 9,500 km of pipelines currently built on permafrost, up to half are expected to be at high risk by 2060. The bill for maintenance could exceed $35 billion a year, he estimates.

Wheat as a weapon

History has shown that Russia is not particularly reliable when it comes to grain supplies. In 2010 the country restricted its grain exports amid a serious drought, causing bread shortages in the Middle East that led to the Arab Spring. More recently, during the coronavirus pandemic, Russia imposed export quotas on wheat, barley and corn.

In a food context, Russia’s war with Ukraine makes sense.

Considered the breadbasket of Europe, 71% of Ukraine’s land base is agricultural. The region is also home to a quarter of the world’s highly fertile black soil, or chernozem. While Russia exports most of the world’s wheat, Ukraine ships the highest amount of seed oils.

Russia is especially vulnerable to climate change, with two-thirds of its land mass sitting on permafrost that is rapidly thawing due to an Arctic region that is warming much faster than the rest of the world.

Remember, the ground’s ability to support buildings across the country’s frozen north is expected to degrade by up to a third by 2050, creating an infrastructure disaster that could cost $132 billion.

So far, Russia has done little to protect its northern infrastructure, and with climate change only getting worse, the future looks bleak.

According to a 20-year study (1980-2000) quoted by The Economist, most of the damage to structures in parts of Russia covered by permafrost was due to poor maintenance: “If local authorities cannot even get the basics right, then large sections of the Russian Arctic may end up being abandoned altogether.”

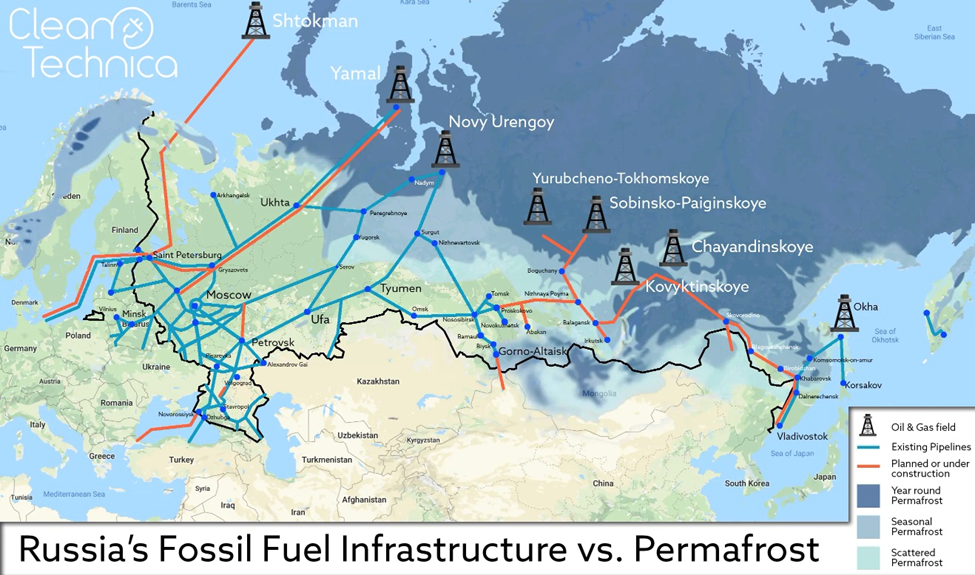

Think about what that could mean for mining and oil & gas extraction. Most of Russia’s oil and gas network is built on permafrost, and almost all of its oil & gas fields are under permafrost, as the map below by Clean Technica shows.

The publication notes that the permafrost is rapidly thawing and could lead to a total collapse of Russia’s oil network:

The production capacity of all existing oil and gas facilities has already declined because the foundation can no longer bear the load. Some have declined as little as 2% and some have declined by more than 20% since the 1990s. This also puts at risk all current development plans and facilities that are currently under construction that are supposed to supply oil and gas to China…

There are a few things we can be certain of. The first is that this is going to cost Russia a lot of money. Russia will either have to keep decreasing oil production to prevent infrastructure from collapsing like this or build a lot more infrastructure to spread the weight, and hopefully build it in a way that can survive melting permafrost, if such a thing is even possible at all. Likely, it will be a combination of these things.

The war and Russian energy

Given what we know about Putin’s motivations, explained at the top of the article, only the most cynical would conclude that the war in Ukraine is all about oil, right? I’ve often found that being right is not about being less paranoid, but not paranoid enough.

Consider the following key points, detailed in Byline Times, a news site that touts itself as “providing a platform for freelance reporters and writers to produce fearless investigative journalism not found in the mainstream media” (text has been compiled and edited):

- Putin’s efforts to centralise state control over the country’s most productive enterprises, run by an incestuous clique of oligarchs, has been highly successful. It has resulted in Russia becoming the world’s number one exporter of oil, gas and wheat, the latter produced through intensive fossil fuel-based industrial agriculture.

- Russia’s internal oligarchic autocracy and military structures are fundamentally premised on its extraction-based economy, which depends on the global consumption of Russia’s fossil fuel commodities. Russian power, then, is an integral part of a capitalist world system in which the vast majority of countries in every major region of the world are dependent on fossil fuels. But this system – both on the global scale and within Russia – is in decline.

- In January 2022, oil and gas-related taxes and export tariffs accounted for 45% of Russia’s federal budget according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), and the energy sector contributes some 25% of the country’s GDP. The implication is stark: the total disruption of fossil fuel industries over the coming decades represents economic Armageddon for Russia.

- In his 2014 book, ‘Clean Disruption of Energy and Transportation: How Silicon Valley Will Make Oil, Nuclear, Natural Gas, Coal, Electric Utilities and Conventional Cars Obsolete by 2030’, Silicon Valley entrepreneur Tony Seba projected that solar, wind, batteries (SWB) and electric vehicles (EVs) were on track to become so cheap and efficient they would rapidly displace incumbent fossil fuel energy and internal combustion engine vehicles by around 2030. Seba warned that due to the acceleration of the clean energy disruption, US military leaders would need to consider the probability of Russian aggression during the 2020s. As incumbent energy industries become increasingly obsolete through this decade, so too would the centralised military and geopolitical architectures they depend on. Peak oil demand would leave a powerful petro-state like Russia – with its history of military adventurism – few options but to resort to aggression to maximise extraction opportunities.

- Oil isn’t running out. We have more than enough to fry the planet several times over. But its resource quality is declining. We now need more energy than ever before to keep extracting energy.

- In 2013, HSBC forecasted that Russia would hit peak oil between 2018 and 2019, experiencing a brief plateau before declining by 30% from 2020 to 2025. Fitch Ratings came to pretty much the same conclusion, noting that only further exploration in remote locations in Siberia over many years might make up for this decline – a task that would require oil prices above $100 to become economically feasible.

- Bloomberg anticipated that EV sales “could displace oil demand of 2 million barrels a day as early as 2023. That would create a glut of oil equivalent to what triggered the 2014 oil crisis.” As we entered the 2020s, in other words, Russia would face a perfect energy storm: the prospect of evaporating demand due to the accelerating SWB and EV disruptions, alongside a crisis of declining domestic fossil fuel resource quality.

- The pandemic accelerated the oil price collapse as global lockdowns crushed demand even further. The result, for the first time in history, was negative oil prices. Covid thus compounded the impact of technology disruptions that were already helping to drive down fossil fuel demand. And it offered Russia a glimpse of what could be in store in coming years.

- By 2021, oil prices were rushing back up as re-opening economies demanded more resources. The sudden oil price spikes were a boon to the Russian economy. They reinforced the sense that the key to Russia’s fortunes was making sure the price is right. This is why Putin’s war was at first seemingly welcomed by many of the world’s autocratic petro-states. Meanwhile, though, Russia’s own Energy Ministry was seeing the writing on the wall, warning in April 2021 that Russian oil production might never recover to pre-Covid levels. Although Russian oil production was expected to continue growing over the next decade, the government’s most probable scenario was that production would fail to reach 2019 levels of 11.3 million barrels a day (mbd). Instead, it would hit a lower peak of 11.1 mbd by 2029, before entering a process of terminal decline that would accelerate from 2035 onwards.

- With its energy export-dependent economy facing an irreversible and intensifying contraction that would undermine the existing oligarchic status quo, the bedrock of everything Putin has attempted to build is bound to unravel. Enter the war in Ukraine. It has offered a geopolitical mechanism to lift oil prices to triple-digit levels, consolidating Russia’s ability to maximise oil revenues despite the prospect of decline. This suggests that conventional analysts have fundamentally misread Putin’s goals in Ukraine. Putin had no intention of launching a short war in Ukraine that would end quickly with total occupation and control of the country.

- US military sources believe that Russian forces are deliberately withholding the full extent of their firepower, calibrating the levels of violence to “keep destruction and pressure at a very careful, just-bad-enough level to keep some advantage.” This is consistent with the conclusion that Putin doesn’t want a decisive military victory in Ukraine, but instead is using it as leverage to reshape the regional geopolitical order by creating a state of permanent hybrid war in Europe, a boiling pot of instability.

- The war in Ukraine, seen through this lens, is Putin’s last stand – a desperate effort using his only remaining tool, the Russian army, to shore up the remaining vestiges of declining Russian imperial power against the inexorable forces of global energy transformation. The war has provided Putin with the boon of triple-digit oil prices, enriching Russian energy firms and bolstering Russian state cash reserves. It has inflated prices for critical materials for the clean energy transformation where Russia and Ukraine play a major supply role, such as nickel, copper, aluminium, palladium, neon and krypton. It has extended Russian military operations into a territory long-sought by Putin as part of a bid to consolidate influence over former Soviet states.

- However, if Putin’s hope was to restore Russia’s glory as a world power, his war in Ukraine has achieved exactly the opposite: it is accelerating Russia’s loss of its most important markets for energy and minerals in Europe and beyond, amplifying the systemic processes already well underway that will culminate in the utter evisceration of Russia’s fossil fuel economy over the next decades. If the Ukraine conflict fails to serve this purpose, the creation of further conflicts in other former Soviet states with important oil industry links may well remain an option in coming years. And even if Putin backs down today, the inevitable escalation of the Russian economic crisis as these processes unfold could spur further outbreaks of regional militarism. As such, the war in Ukraine offers a taste of things to come, not merely in Europe. The same processes impacting Russia will affect the world’s other major fossil fuel producers. The next two decades will be a period of unprecedented geopolitical turmoil.

Conclusion

A warming climate brings a whole bunch of problems for northern hemisphere oil, gas and mineral producers like Russia.

The Kremlin under the direction of President Putin has carefully consolidated control of the country’s natural resources to become the world’s leading exporter of oil and wheat. Russia is also the sixth largest supplier of global commodities.

Putin must have known that this status gave Mother Russia tremendous clout over the EU, which gets 40% of its natural gas from Russia. He would have also known that invading Ukraine would send oil, gas and wheat prices sky-high, enriching the country’s foreign cash reserves. Every barrel of oil and cubic foot of natural gas Russia sells to Europe, is adding to Putin’s war chest and prolonging the war.

The Russian economy is greased by fossil fuels. Certainly Western sanctions have hurt Russian individuals and businesses, but its oil majors continue to operate.

Putin has no motivation to bring the war to a close. The country may have to sell less gas to Europe but other buyers will materialize, and have. As long as the global demand exceeds supply, it’s all good for Team Putin.

Of course, continuation of the fossil fuel world order comes with a price: the acceleration of global warming. As mentioned, Russia is among the countries most likely to be impacted by rising temperatures. Much of its oil and gas pipeline infrastructure is sitting on permafrost and nearly all of its oil & gas fields are under permafrost. Most of the country’s nickel mines are in the Arctic. The ground is thawing, threatening to unlock millions of tonnes of methane and CO2, serious diseases like anthrax, and to topple buildings, break pipelines, and damage roads, bridges and railways.

Repairing it is going to be very expensive. If oil and gas continues to be usurped by renewable energies and electric vehicles, the transition will diminish Russia’s ability to pay. So far the country’s leadership hasn’t shown itself up to the task of rebuilding/ relocating its infrastructure to safer ground.

I think that Byline Times is right in its conclusion that the war in Ukraine is just the beginning of a number of regional conflicts that are started by other major fossil fuel producers, like those in the Middle East. Like Russia, they have everything to gain by prolonging the demand for oil.

Some expect a seamless transition to solar, wind and batteries, but recent history shows it will be anything but.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.