5 reasons why food will get more expensive

2022.05.12

A comparison of this year’s grocery bills to last year’s yields a simple yet terrifying conclusion: food prices are going up (which is to be expected), but at a rate that is approaching unaffordable territory for consumers (which, for some, is not so expected).

Indeed, grocery costs are rising at the fastest rate in 13 years, driven by major swings in the price of dairy, meat and pasta, according to Statistics Canada’s latest consumer price index.

Food prices in Canada rose by 8.7% in March compared with the previous year, the biggest year-over-year increase since 2009, StatCan data shows.

Globally, food prices have been soaring since the turn of the year, with the FAO Food Price Index reaching a record high during the month of March. This is after coming off a year in which prices have already jumped 28%, the highest in a decade.

For those hoping for a “cooldown” of food prices, unfortunately that is unlikely to happen anytime soon. Below are reasons why food will continue to get more expensive as we continue to see out what is considered an onerous year for consumers worldwide:

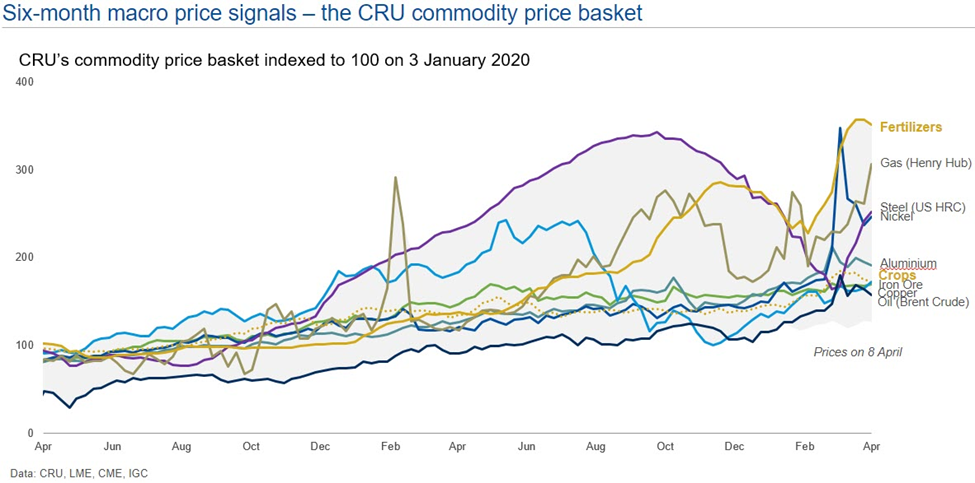

- Soaring Fertilizer Prices

For any product sold on the market, its price is often determined by that of its inputs, and food is no different. Most of the food we consume — such as bread, milk, meat, fruits and vegetables — comes from the labor of agricultural activities.

The key input in agriculture is fertilizers, which farmers use to supplement natural soil nutrients, antibiotics to prevent animal diseases, and pesticides to protect crops against animals, insects, weeds and various microorganisms. Fertilizers used by farmers today are synthetically created, as they have proven to produce much larger crop yields than organic sources for over a century.

Thus, it should come as no surprise that once the cost of synthetic fertilizers rises around the world, food prices would naturally increase.

That’s exactly what is happening around the world right now; the cost of raw materials in the fertilizer market — ammonia, nitrogen, nitrates, phosphates, potash and sulphates — has gone up by 30% since the start of 2022. Their prices have now exceeded those seen during the food and energy crisis in 2008, according to British commodity consultancy CRU.

After touching a record-high in March, fertilizer costs haven’t shown any signs of slowing down in the following month either, as all eight major fertilizers tracked by DTN had seen increases during April. DTN’s National Index of Anhydrous, for example, was up 122% from a year ago.

As the price of fertilizers continues to soar, so will our food products, as farmers around the world will be forced to cut their fertilizer use.

- Lower Crop Yields

A direct consequence of soaring fertilizer prices is the threat of declining food production, as well as quality, in many parts of the world.

In the Philippines, where urea (a key nitrogenous fertilizer) is now about 3,000 pesos (about $57) per bag, crop yields could drop by as much as 10%, the president of Philippine Maize Federation estimates. In other places, the yield outlook is even worse.

In Peru, staples such as rice, potatoes and corn could tumble as much as 40% unless more fertilizer becomes available. The International Rice Research Institute predicted crop yields could drop 10% in the next season, meaning there’ll be 36 million fewer tons of rice — enough to feed 500 million people.

In Brazil, the world’s biggest soybean producer, a 20% cut in potash use could bring a 14% drop in yields, according to industry consultancy MB Agro.

In Costa Rica, a coffee cooperative representing 1,200 small producers sees output falling as much as 15% next year if the farmers miss even one-third of normal application.

In West Africa, falling fertilizer use will shrink this year’s rice and corn harvest by a third, according to the International Fertilizer Development Center, a food security non-profit group.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, food production could drop by about 30 million tons in 2022, equivalent to the food requirement of 100 million people, the IFDC forecasts.

“My biggest concern is that we end up with a very severe shortage of food in certain areas of the world,” Tony Will, the chief executive of the world’s largest nitrogen fertilizer company CF Industries Holdings, recently said in a Bloomberg interview.

- Rising Energy Prices

The culprit behind the skyrocketing fertilizer and consequently food costs is the rise in energy prices, as the production process of fertilizers is very energy-intensive.

Natural gas is used as a raw material to produce ammonia, the building block for all nitrogen fertilizers, which account for most of the world’s fertilizer consumption. Typically 60% to 80% of production costs are natural gas costs. In some countries such as China, coal is also gasified into ammonia and used for manufacturing fertilizers.

Thus, it’s inevitable that once natural gas and coal prices start to increase, so does the cost to make fertilizers for agricultural use. In the US, natural gas prices recently hit their highest since 2008, while its coal prices also topped $100/ton for the first time since then.

Due to higher natural gas prices in Europe, various fertilizer companies have already been forced to shut down, leading to concerns around food supply. India, one of the top producers of coal and agricultural commodities, is currently undergoing its biggest power crisis in years.

As surging energy prices drove inflation in major economies to multi-decade highs and caught central bankers off guard, the next source of pressure could come from food prices, according to a report last year by Nomura Holdings.

Compounding the issue, food producers also have to compete with other industries for energy use; the production of biofuel, for example, diverts crops away from the agricultural sector, while the production of lithium-ion batteries requires chemicals used in the fertilizer production.

- War in Ukraine

The repercussions of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have certainly been felt by consumers around the globe, as supply chain disruptions and economic sanctions have made everything including food more expensive.

Historically, Ukraine is known as the “breadbasket of Europe”, given that it has some of the most fertile soil in the world because of the climate, and its farmland is relatively cheap. About 25% of all global wheat exports are through Ukraine. Russia is also a major producer of agricultural products, as well as a top exporter of nitrogen fertilizers.

As such, the ongoing war in Ukraine can be seen as a major disruptive force in the global food market, in particular for the impact it has had on international shipping and the aforementioned input costs.

Barclays chief UK and senior European economist Fabrice Montagné and head of economics research Christian Keller recently told CNBC that “renewed shipping and transportation difficulties and, more importantly, the impact of Russian sanctions on global supply are set to stretch global markets even further, akin to the 2008 global food crisis.”

Wells Fargo head of global real assets John LaForge and global strategist Gary Schlossberg added that given the weight of Russian supply, other countries will only be able to “partially” fill global supply gaps.

- Monetary Policies & Stimulus Spending

At the heart of the global inflation problem — not just for food prices — is the expansionary policies implemented by central banks across the world. It has been well documented that over the years, loose monetary policies have been contributing to inflation expectations while supporting economic growth.

Then, an unexpected event known as the Covid pandemic amplified the inflation concerns following unprecedented increases in spending by governments. Historically, economic relief packages have often resulted in high prices for goods and services, and this year, we’re finally starting to experience the burst in inflation.

Even before Covid, there were fundamental supply-demand factors that pointed to a surge in food prices, according to Nomura analysts. Expectations of food inflation are now greater as the effects of central bank policies begin to bite back on economies.

This effect is profound in the US, where its inflation is continuing to rise and has reached 8.5%, the highest in 40 years. Globally, price levels have gone up by 6%, still far higher than the generally accepted 2% level.

As food has a much larger weighting in the CPI than energy, the inflationary pressures on this sector would be more significant. “It’s in food prices where the seeds of the next crisis may already be sown,” Nomura analysts said in a report.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.