A new “Paris Agreement” sets the plastic age on countdown

2022.04.04

March 1, 2022 could well be looked back upon as a monumental day in the history of mankind.

That was the date on which nearly the entire world agreed on the planet’s first global treaty to tackle plastic pollution.

At a meeting of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) in Nairobi, Kenya, as many as 175 countries passed a resolution on the world’s first treaty to end the “plastic crisis”, which has gotten worse each year following the plastic age of the 1950s.

Many describe this as the most significant environmental deal since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Some even call it the world’s most ambitious environmental action of the 21st Century, comparing it to the 1989 Montreal Protocol that phased out ozone-depleting substances.

“Plastic pollution has grown into an epidemic. With today’s resolution we are officially on track for a cure,” Espen Barth Eide, President of UNEA, stated upon passing of the resolution.

This legally binding treaty encompasses all stages of plastic, from production to consumption and disposal. Inger Anderson, executive director of the UN Environment Program, said the resolution text “speaks to full life cycle; it speaks to a financing mechanism; it speaks to understanding that some countries can do it more easily than others.”

Following 115 years in existence and over half a century of mass production, it seems as though we have finally said “enough is enough” to a world filled with this synthetic material.

Our Plastic World

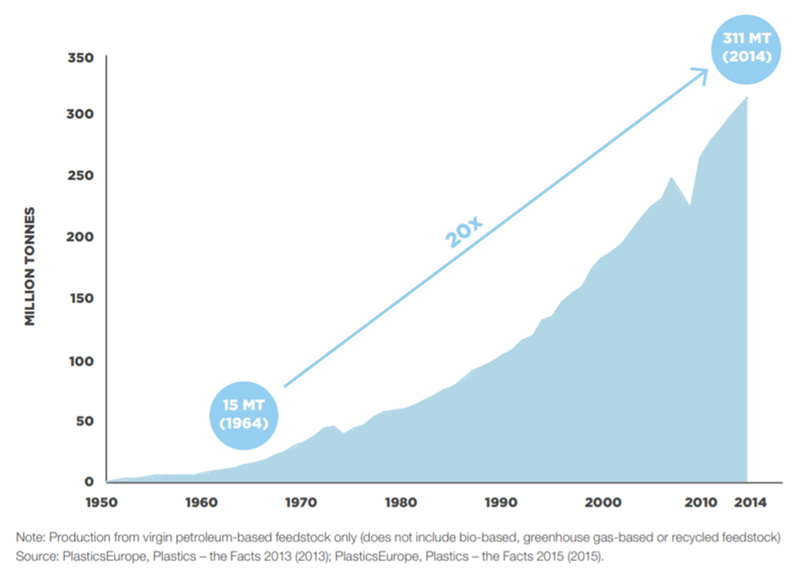

A 2016 study by the World Economic Forum estimates that global plastic production went from 15 million tonnes in 1964 to 311 million tonnes in 2014 — a gigantic twenty-fold increase during a 50-year period. Now, the world produces more than 380 million tonnes of plastic, up to 50% of which are for single use.

Production is expected to at least double again over the next two decades, then quadruple by 2050, the WEF predicts.

Since plastic products are often discarded after a single use, these materials are now scattered across every corner of the Earth, from the trenches of the ocean to the top of mountains.

In the ocean alone, there are an estimated 150 million tonnes of plastic, with around 8 million tonnes entering the seas every year — the equivalent of dumping a truckload of plastic garbage every minute.

About a quarter-million tonnes is thought to be floating, while the rest either sinks or washes up on beaches. Plastic isn’t only found on the beaches or off the coasts of large cities. Scientists are becoming alarmed at finding plastics in relatively pristine waters, far from population centers.

A report by the Pew Charitable Trusts estimated that about 11 million metric tons of plastic waste enter the marine ecosystem on an annual basis, and without immediate and sustained action, that amount will nearly triple by 2040 to 29 million metric tons per year. That’s the same as dumping 110 pounds of plastic on every meter of coastline around the world.

Ironically, plastic is a scourge of modern society because the material is virtually indestructible, a trait that made it appealing to consumers in the first place.

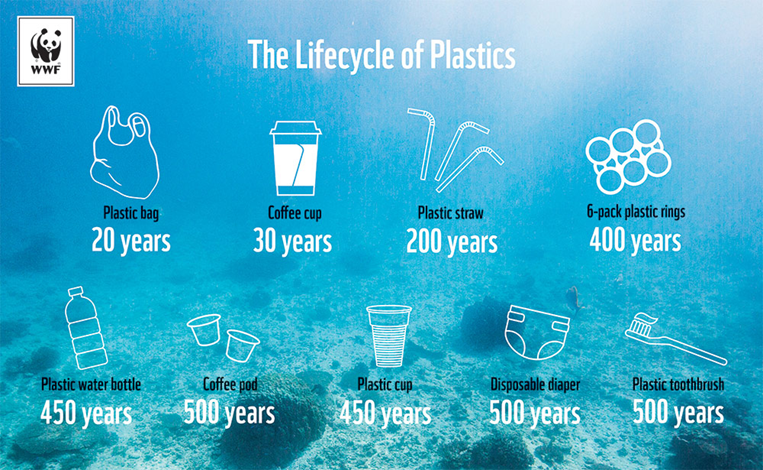

Most plastic products have long lifespans. Plastic bags, for example, can take up to 20 years to decompose, while takeaway coffee cups, despite being mostly paper, have a plastic lining that will endure for 30 years. Some items, like coffee pods, disposable diapers and plastic toothbrushes, could stay in landfills for five centuries!

So, the plastic waste piling up in our landfills, or those scattered along coastlines, or swimming in the ocean, are only going to proliferate as long as more are being churned out from production lines. It’s not even far-fetched to say that the world is literally drowning in plastic.

Waves of Plastic

The impact of plastic waste on the planet’s marine ecosystems has been well-documented in the media.

Whether from reading National Geographic magazines or watching a docuseries filmed by Netflix, we’ve seen how marine animals (i.e. sea turtles, seabirds) can become entangled in plastic fishing nets or are impaled by plastic straws.

Others mistake the colorful plastic fragments for food and eat them, causing them to die of starvation as their stomachs become filled with plastic. Some also suffer from lacerations, infections, reduced ability to swim and internal injuries.

National Geographic says the problem of discarded plastic is so severe, that if nothing is done, by 2050 the oceans will contain more plastic than fish, ton for ton.

Plastic is also one of the biggest threats to coral reefs, according to National Geographic. The long-running nature magazine says over 11 billion pieces of plastic have been found on a third of coral reefs in the Asia Pacific — a figure that is expected to grow to 15 billion by 2025.

Plastics floating on ocean surfaces also help transport invasive marine species, thereby threatening marine biodiversity and the food web.

According to the UN, at least 800 species worldwide are affected by marine debris, and as much as 80% of that litter is plastic. A recent report published by WWF showed that 88% of marine species it studied are being affected by severe contamination of plastic in the ocean. Many marine animals have ingested these plastics, including those commonly consumed by humans.

Plastic that enters the ocean gets exposed to UV radiation, oxygen, high temperatures and microbial activity. Some plastics, those made from bacterial polymers, are naturally biodegradable. Others, such as takeaway food containers, will only decompose when exposed to prolonged temperatures above 50 degrees Celsius, conditions found in an industrial composter that cannot be replicated in the oceans.

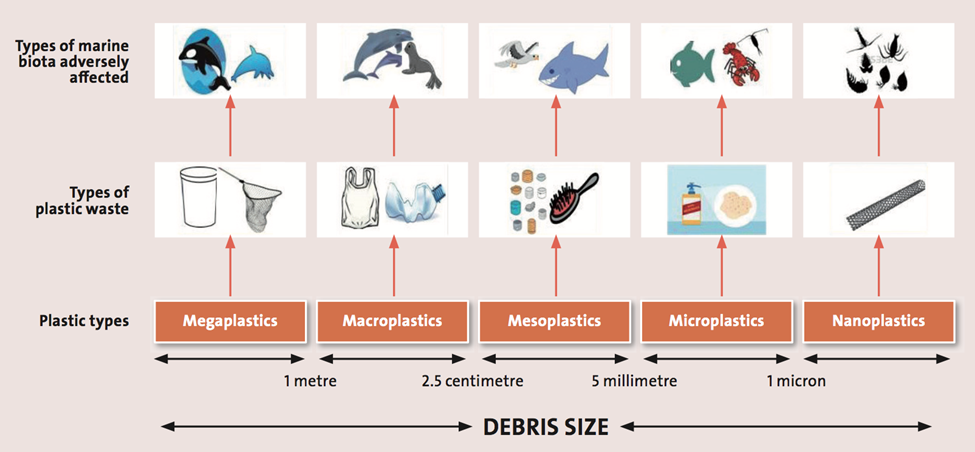

Eventually the saltwater, sun, wind and waves break the plastics down to tiny particles that are carried by ocean currents to even the most remote corners of the Earth. These particles, known as microplastic, are one of the major culprits behind the pollution problem.

Microplastics have been found in tap water, beer, salt and are present in all samples collected in the world’s oceans, including the Arctic.

Even if we stop throwing plastic objects into waterways and sewage systems, microplastics can still enter the ocean via daily human routines. A study cited by Water World in 2016 showed that more than 700,000 microscopic plastic fibres are released into the environment during each cycle of a washing machine. By 2019, it was estimated that 1.5 million trillion microfibers were present in the oceans around the world.

Because they’re so small (<5 mm), microplastics are easily ingested by marine life, which accumulate and carry the harmful material in their bodies. As part of the natural order, these tiny pieces of plastic can also work their way up the food chain, leaving a devastating and long-lasting effect on life beyond the marine system.

Dirty Chemicals

What makes microplastics so problematic? The answer comes down to chemistry.

Plastic is a polymer molecule consisting of repeating identical units (homopolymer) or different sub-units in sequences (copolymer). Plastics are further categorized as thermoplastics, which soften when heated and can be molded, or thermosets, which cannot be molded or heated. Both types cause pollution in a marine environment.

Plastics also contain chemicals to improve their properties that cause harm when they enter the food chain.

Although hundreds of thousands of plastic materials have been invented, only six are extensively used: polyethylene terephthalate (PETE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC-U), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS), or Styrofoam.

In the ocean, despite weathering that reduces plastics like water bottles and shopping bags to tiny particles, the original plastic polymer remains intact, unless it is converted into carbon dioxide, water, methane, hydrogen, ammonia and other inorganic compounds — a process that doesn’t happen in a marine environment.

Especially worrying are the “nanoplastics” — particles that are so tiny (<100 nm) that they are able to penetrate human cell walls. Of course, nanoplastics are invisible to the naked eye, or even under a simple microscope, making them impossible to be filtered out.

One of the surprising facts about microplastics is how entrenched they are in the global ecosystem.

Small pieces of plastic have been detected in lakes and seas, in the sediments of rivers and deltas, and in the stomachs of the smallest and largest organisms, from plankton to whales. One study found that every square kilometer of the world’s oceans has 63,320 plastic particles floating on the surface.

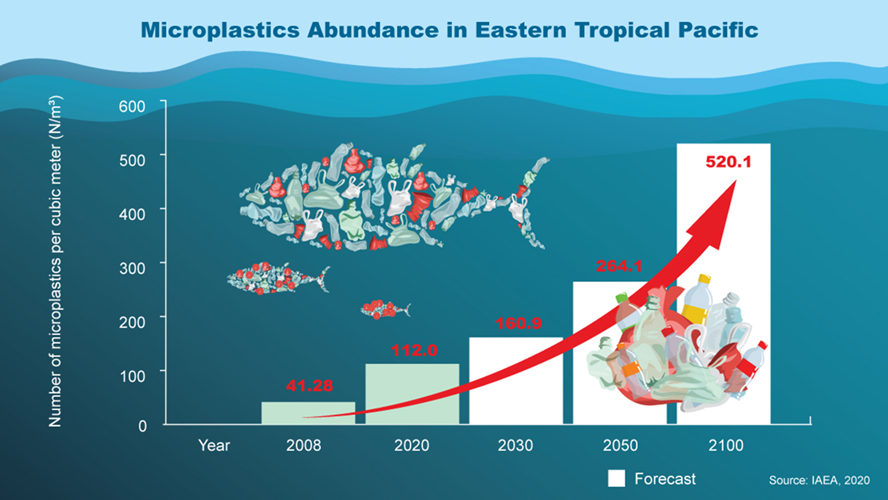

In the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean — home to some of the world’s most unique marine reserves, including the Galapagos Islands in Ecuador — the amount of microplastics is expected to increase some 3.9 times by 2030 compared to 2008 levels, according to IAEA studies.

By 2050, this figure could almost double again, rising by 6.4 times compared to 2008 levels. Without significant action, the amount of plastics in the ocean is projected to be more than 10 times higher by 2100, IAEA estimates.

There are a number of ways that plastics get into the environment. Microbeads used as exfoliants in beauty products escape water filtration systems. Other primary sources include plastic powders in molding, and plastic nanoparticles in a variety of industrial processes.

The extensive and indiscriminate use of food packaging, car tires, paints, personal care products (eg. toothpaste) and electronic equipment are some more contributors to microplastic contamination.

Microplastics can also become part of the water cycle and be delivered back to Earth as rain or snow.

Scientists think that tiny particles shed by anything plastic get incorporated into water droplets when it rains, then wash into lakes, rivers and oceans. When the water evaporates, the particles can end up in groundwater. They are then consumed by animals and people via drinking water and food, or simply breathed in.

If nano-scale plastic has become prevalent in drinking water, oceans, rainwater, and the animals that mistakenly eat them, it’s not a stretch to say that microplastics are probably in our food.

According to Food Safety magazine, microplastics are present in various food products, including seafood, as well as in bottled water. In addition, microplastics can also help introduce other contaminants to foods.

Persistent organic pollutants and other toxins in water can also be attracted to these particles. Once consumed by plankton, these contaminants are passed through the food chain to small fish and eventually to humans. While their impact on human health is still up for debate, high volumes of microplastics in rats have been found to cause cancer.

Several chemicals used in the production of plastic materials are known to be carcinogenic and to interfere with the body’s endocrine system, which could potentially lead to developmental, reproductive, neurological and immune disorders.

Microplastics In Our System

The problem is not only the nano/microplastics, but the pollutants they carry with them.

When plastics move through the food chain, the attached toxins also move, and accumulate in animal fat and tissue through a process called bio-accumulation. Chemicals added to the plastic during the production process can leach from the plastic into the body of the animal that has eaten them.

Potential adverse effects, at high enough concentrations, may include immunotoxicity responses, reproductive disruption, anomalous embryonic development, endocrine disruption, and altered gene expression.

While microplastics’ effects on human health have not been widely studied, it’s safe to say that inhaling or ingesting them should be avoided. This may be extremely difficult however; one study found plastic fibers in 87% of the human lungs studied.

Recently, microplastics were found in human placentas, though more research is needed to determine if this is a widespread problem. Another found that microplastics can latch onto the outer membranes of red blood cells and may limit their ability to transport oxygen.

A haunting discovery was made this month when scientists from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam detected polymer particles in human blood for the first time, raising alarm bells for our future survival in a world full of plastics.

“Our study is the first indication that we have polymer particles in our blood – it’s a breakthrough result,” Professor Dick Vethaak, an ecotoxicologist at the university, told the Guardian.

Vethaak’s previous work had shown that microplastics were 10 times higher in the feces of babies compared with adults, and that babies fed with plastic bottles are swallowing millions of microplastic particles a day.

Chemicals associated with plastics are known to be harmful. The most well-studied is BPA — found in plastic packaging or food storage containers. When BPA leaks into food it can interfere with reproductive hormones in women.

Another chemical, phthalates es, is used to make plastic flexible. The presence of phthalates in a petri dish was shown to increase the growth of breast cancer cells.

In a limited study, Canadian researchers estimated the average person ingests over 74,000 plastic particles a year. Examining just a few food sources including fish, shellfish, sugar, alcohol, honey, bottled versus tap water, plus air, the study authors found the most microplastics in air, bottled water and seafood.

Mussels and oysters harvested for eating reportedly had 0.36 to 0.47 particles per gram, meaning that shellfish consumers are ingesting up to 11,000 pieces of microplastic per year, according to Healthline.

Plastic ‘Consumers’

It goes without saying that we have been consuming plastic, literally, for decades.

Out of the millions of tonnes of plastic produced each year, who knows how much of the material (and chemicals) has been infused with the human body and passed onto the next generations.

What’s worse is that we seem to have been engineered to embrace their existence. This is because they are, admittedly, so useful, so much so that it’s hard to even imagine a world without plastic products by our side.

The irony in that, however, is what we view as a convenience for our survival may be the very thing that destroys us. More and more studies have shown that plastic material can eventually find its way into marine animals, and eventually the human body.

This would not have been a problem if plastics can decompose and simply vanish. But since we wanted plastics to be so indestructible, that’s not possible, which, again, is ironic. Even broken down into small pieces, the chemicals used to make plastics are still able to contaminate our water supply.

Theoretically, recycling plastics would solve everything, but in reality, it’s a pipe dream. Nowadays, plastics have become so commonplace – plastic bags, packagings, straws and utensils, coffee pods, plastic microbeads – and there are simply too many of them to account for.

More than 40 years after the launch of the now omnipresent “recycling” symbol, only 14% of the plastic packaging is collected for recycling, according to the World Economic Forum. For plastic containers, the recycling is even lower at 10%; the rest ends up in landfills, rivers, lakes and finally, the ocean.

This means almost all of the plastic products we have used in our lifetime could have ended up in the natural environment and our food sources.

Conclusion

Thankfully, the news on plastic pollution isn’t altogether bleak. Agreement on the world’s first-ever plastic pollution treaty could mark the turning point in human history in our efforts to reverse the damages we have done.

Just exactly what measures should be enacted under this global treaty remain to be seen, but at least this deal would provide a framework for businesses and economics around the world to follow. Work has already started on how to implement the treaty by 2024.

“The best way to tackle plastic pollution is to prevent it in the first place. By covering the whole supply chain, a global agreement to tackle plastic pollution can support upstream solutions such as reducing or replacing plastic in products,” said Professor Steve Fletcher at the University of Portsmouth, who advises the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) on plastics issues.

“There is a broad consensus that global coordination is best achieved through a legally binding agreement,” Fletcher added.

“This is only the end of the beginning, we have a lot of work ahead of us,” said the head of the United States delegation in Nairobi. “But it is the beginning of the end of the scourge of plastic waste for this planet.”

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks.

Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.