The limits to growth: Why the West will struggle to find enough metals to supply simultaneous demand drivers

2022.02.25

In 2021, commodities outperformed all other asset classes, and they are expected to do the same in 2022.

A commodities “super-cycle” can happen in the late stages of an economic expansion, when growth is so strong, companies can’t produce enough commodities to keep up with demand. This is the situation the world economy finds itself in as it recovers from the pandemic, which slammed the brakes on global growth in the spring of 2020. By first halting and then restarting supply chains, supply and demand fundamentals for raw materials were thrown out of whack. Also, consumers’ spending habits shifted to purchasing more goods than services. Goods inflation has exceeded services inflation, due to higher oil prices, a topic we explored in a previous article.

According to Bloomberg investors are putting more money into commodity funds than at any time in the last decade, seeking protection against 40-year high inflation which in the US is running at 7.5%.

Citigroup estimates retail and institutional money in the sector at close to $700 billion, the most since at least 2007, with broad-based commodity exchange-traded funds now holding more than $21 billion, also the most since 2007.

Commodities super-cycle: 2003 vs 2022

The last super-cycle was 2003-11. From the bottom in 2003 to the peak in 2008, commodities rose over 300%.

The commodities super-cycle of the 2000s collapsed in the Great Recession of 2008, then resumed from 2009 to 2011. It ended in the bear market of 2011-15.

Many are pointing to the formation of a new super-cycle, driven not by fossil fuels and the rise of China, but by “green” metals needed for technologies that mitigate the effects of climate change. This includes the electrification of the global transportation system and the decarbonization of fossil-fueled energy sources (coal, oil, natural gas) as the world’s energy matrix runs more on renewables, chiefly wind, solar and hydroelectric power.

Let’s be clear: the super-cycle of 2022, if we may be so bold as to call this year the beginning, is completely different from the last one that started in 2003.

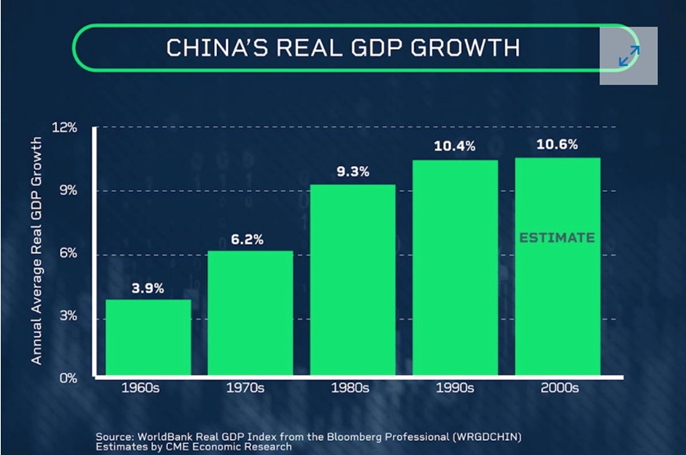

The main difference is that 2003-11 was all about feeding China’s insatiable thirst for energy and commodities. The country needed copious amounts of coal and iron ore to make steel, the foundation of its modern economy, as well as copper for construction, telecommunications and transportation. Many more metals including zinc, lead, nickel and tin, were part of the mix. The whole enterprise was fueled by oil and gas, for which China was basically a bottomless pit.

Today it’s not only China that needs a multitude of metals. Many countries have infrastructure deficits they need to try and reduce, along with the global threat of climate change, the evidence for which is growing stronger each year, and is driving economies to rapidly shift away from carbon-emitting energy sources to low-carbon or carbon-free alternatives. Population growth, which infers a greater need for food and manufactured goods, is another important commodities demand driver.

Fast forward a decade from the end of the last commodities supercycle in 2011, and we have a very different situation with respect to metals supply and demand.

On top of surging demand for minerals needed to feed new solar and wind power installations, lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and grid-scale utility storage, and traditional “blacktop” infrastructure programs (e.g. roads & bridges), we have current and emerging structural deficits for several metals, that will keep prices buoyant for the foreseeable future.

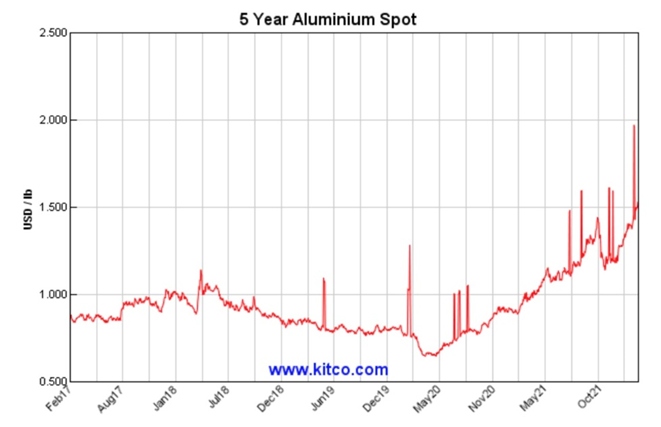

For example the aluminum market is running low on supplies, causing prices to near a 13-year high earlier this month.

Nickel is similarly undersupplied. It jumped to an 11-year high of $25,000 a ton, Monday, on fears of dwindling supplies, continuing to $25,625 after Russian forces invaded Ukraine (more on that below). According to Bloomberg the base metal used in stainless steel and lithium-ion battery cathodes is the top performer on the London Metal Exchange this year, climbing amid a wave of forecasts that supply will fall short of rapidly growing demand from the electric-vehicle industry.

During the first half of 2021, copper rallied off the back of a sharp recovery in economic activity across the world, led by top consumer China. Also pushing prices higher was the belief that pandemic-related stimulus, plus the global push for decarbonization, will further lift demand for the industrial metal.

That saw copper prices break the $10,000/t level towards the end of April, the first time that has happened in a decade, and surge to a new high the week after.

In the second half, copper received another boost amid an energy crisis that affected several major producers and threatened global supply. In October, a surge in metal orders from warehouses in Europe saw the LME inventories plunge by as much as 89%, to its lowest in 47 years.

All these events factored into copper’s record-breaking year, though many believe that the red metal is just getting started.

Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research for Goldman Sachs, in January reiterated his view that we are at the beginning of a decade-long commodity super-cycle. Currie told CNBC’s ‘Squawk Box” that the fundamental setup in the commodities complex, including oil and metals, “remains incredibly bullish.”

Currie gives two reasons for this. First is the fact that global oil inventories are about 5% below their five-year moving average, putting upward pressure on prices.

Second, investing in the oil & gas industry has gone out of favor, with ESG headwinds posing a significant challenge for a sector that badly needs new investments, for production to keep up with demand. Under-investment in new mines and new oil discoveries has resulted in a severe supply-demand imbalance in a number of areas.

Saudi Arabia has warned that, without re-investing in the oil industry to find more deposits, the world could be short 30 million barrels a day in eight years, representing about a third of global supply. Last weekend Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman said the focus on renewables and the campaign against oil investments is a mistake. “[N]et-zero does not mean zero oil,” he said, via Oilprice.com. The country plans on raising its crude oil capacity by a million barrels a day within the next five years.

In the current under-supplied environment, high oil and natural gas prices will be with us for the foreseeable future. Read more

War in Ukraine

The Brent crude oil benchmark exceeded $100/bbl Wednesday, for the first time since 2014, due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. WTI crude was sitting at $96/bbl, at time of writing.

Natural gas prices in Europe, which gets most of its supply from Russia, opened 40% higher Thursday morning, at €125/MWh.

In Chicago trading, wheat and corn prices jumped on worries that shipments from Russia and Ukraine, two major suppliers of grains and edible oils, could be disrupted.

Nickel prices rose 5% to $25,625 per ton, the highest since May 2011, aluminum climbed 4.6% to a record 3,443/t, and palladium prices added 6%.

In fact this week’s commodity price spikes due to actual war in Eastern Europe may be just be the beginning. In a note to clients, JP Morgan’s commodity desk wrote Wednesday that “geopolitical escalation over the last few days has materially increased the risk of further aggravating commodity market imbalances. At this stage of the conflict, it is hard to see a path towards an easy de-escalation.” Consequently, JPM now expects “a steady rise of tensions in Ukraine and a corresponding intensification of sanctions from the West. In that case, the bank warns that “the world could see an extended period of elevated geopolitical tensions and high-risk premium in all commodities given Russia’s far reaching impact on global commodities markets.”

Running short

Most natural resource modeling has greatly overstated the amount of fossil fuels and minerals the petroleum and mining industries will be able to extract. Forecasters assume that as long as we have the technological capability, and resources are still in the ground, extraction will follow.

In fact this model greatly overstates the quantity of future resources that can actually be mined. The reason is because

the world economy tends to run short of many types of resources simultaneously.

Take January 2022 as an example. World Bank Commodities Price Data shows prices were high for a number of materials including fossil fuels, fertilizers, aluminum, copper, iron ore, nickel, tin and zinc.

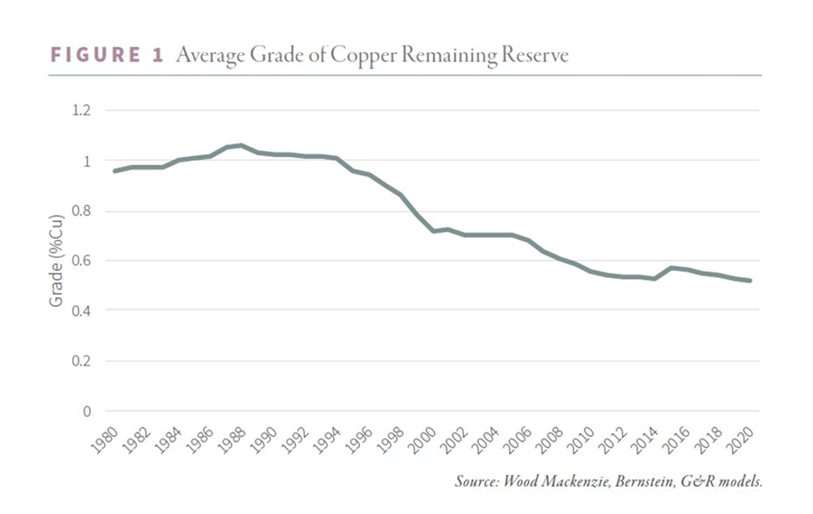

But that doesn’t mean producers will automatically go after these commodities. For several minerals, including copper, grades are declining, meaning more ore has to be mined for the deposit to be economic. More complicated mineralogy often means more complicated, and more expensive, metallurgy.

A report last year by Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates (G&R) found that both greenfield and brownfield copper reserve additions are expected to disappoint through the decade.

According to the New York-based research firm, the number of new world-class discoveries coming online this decade “will decline substantially and depletion problems at existing mines will accelerate.”

Additionally, geological constraints surrounding copper porphyry deposits, a subject few industry analysts let alone investors understand, will contribute to the problems, the report said.

G&R also pointed out that miners have been “artificially” boosting reserves by lowering their cut-off grades when copper prices rise in order to make more profit. But this practice only works to a certain point, when cut-off grades cannot be reduced any further.

By 2015, the industry’s head grade was already 30% lower than in 2001, and the capital cost per tonne of annual production had surged four-fold during that time — both classic signs of depletion.

According to the G&R model, the industry is “approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades,” and brownfield expansions are no longer a viable solution.

“If this is correct, then we are rapidly approaching the point where reserves cannot be grown at all,” the report concluded. This highlights the importance of making new discoveries in establishing a sustainable copper supply chain.

Over the past 10 years, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling by 80% since 2010.

Arguably, we are at the point where no significant new technologies will be invented to make mining more efficient or profitable — unlike the “shale revolution” brought about by directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing i.e. fracking. These processes allowed previously uneconomic “tight” oil and gas formations to be drilled, transforming the United States from a net oil importer to a net oil exporter.

In the same way, farming and ranching have reached the limits of technology. The agricultural reforms and resulting production increases fostered by the Green Revolution are responsible for avoiding widespread famine in developing countries and for feeding billions more people since. Unfortunately though, high-yield growth is tapering off and in some cases declining. This is mostly because of an increase in the price of fertilizers, other chemicals and fossil fuels, but also because the overuse of chemicals has exhausted soils and irrigation has depleted aquifers.

Throw climate change into the mix, and you’re looking at a serious problem.

A warming planet also affects minerals extraction and processing. For example Chile, the world’s biggest copper producer, has problems with water and is having to desalinate seawater used for mining copper in the country’s arid north. We are already seeing major copper mines in Chile having to curtail production due to water shortages brought on by a decade-long drought.

In a thorough analysis of the DRC’s climate vulnerabilities, the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs rated Congo the 12th most vulnerable country to climate change among 181, and the fifth least prepared. The DRC is Africa’s leading copper producer and mines by far the most cobalt of any country.

Last year in central Brazil, the worst water crisis in nearly 100 years made navigation on one of the country’s most important river systems difficult, making it more challenging and costly to get its grains and iron ore to global markets. (last June, flows were @ 55% of the historical average).

Beyond climate change and technical constraints on minerals extraction, there is also the considerable time lag involved in developing new supplies. In Canada and the United States, it can take up to 20 years for a new mine to come online, from the initial discovery phase to commercial production.

Also, natural resource modeling assumes that industry will continue to have people with the skill sets needed to find and run mines. In fact in many countries, mining is retiring more employees than it is bringing in from universities and colleges, setting the industry up for a skills shortage that could impact its ability to deliver new supplies. A study by the Society of Petroleum Engineers found the average age of energy industry employees is 50, while for mining it’s 46.5, compared to the average US workforce age of 40.

Finally, resource nationalism is throwing up a number of impediments to bringing promising deposits into production.

Countries rich in minerals are frequently looking at ways to get more money from miners, the most common tactic being to hike royalty payments.

Governments have also gone beyond taxation in getting more out of the mining sector with requirements such as mandated beneficiation/export levies and limits on foreign ownership:

- Mandated beneficiation/export levies – Governments are imposing steep new export levies on unrefined ores. Minerals processed in-country capture more of the value chain as the products achieve higher prices.

- Increasing state ownership – Miners are easy targets because mining is a long-term investment and one that is especially capital intensive. Mines are also immobile, so miners are at the mercy of the countries in which they operate. Outright seizure of assets happens using the twin excuses of historical injustice and environmental or contractual misdeeds. There is no compensation offered and no recourse.

Risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft tracks incidents of direct expropriation and nationalization, summarizing the degree of risk in an annual resource nationalism index.

Sixty six of 198 countries in the latest (2021) index, or 33%, have tightened their grip on resource wealth since 2017. Latin America stands out as the region where the risk of expropriation and tax increases have increased the most.

There’s another, less familiar form of resource nationalism, the passive-aggressive kind we see in highly developed mining nations like Canada, the United States and Australia. Here, governments are under pressure from environmental, indigenous, and anti-development groups to say no to mining.

Unlike poorer nations whose populations need the metals revenue to pay for important social services and to earn hard currency to buy imports, in the rich, developed West, citizens have the luxury of protest. They are comfortable.

Mining is seen by some as a necessary evil whose environmentally destructive practices should be stopped, or at least, shouldn’t take place anywhere near them. They don’t realize or care that without mining, there would be no modern society: no steel to make bridges, no copper wiring that powers homes and businesses, no uranium to fuel nuclear reactors, no jewelry, no rare earths to make smart phones, solar panels, color monitors and TVs. Usually they want resource extraction halted, at all costs — the minerals or the oil kept in the ground.

The Biden administration in the US and the Trudeau government in Canada have both come out with policies that can be considered anti-mining.

Demand: everything happening at once

Politicians like Biden and Trudeau seem to have their heads in the sand when it comes to an appreciation of the limits to resource extraction outlined above. Biden for example is content to let US allies do the mining, and for American companies to buy their minerals. The assumption is there will always be enough.

But for the first time in history, there is a confluence of demand drivers that threaten to outstrip supply, potentially depriving the United States (and Canada) of the minerals they need to drive the economy in the directions they want it to go.

Not only are metals required for electrification and decarbonization, the so-called green shift, they are also needed to replace traditional infrastructure (think roads, bridges, public buildings), to harden targets vulnerable to climate change (e.g. levies, storm breaks) and to relocate infrastructure and populations in the way of storm surges and sea rise.

A local example is the storm damage done to southern BC highways in the wake of the “atmospheric rivers” last fall. According to early estimates it will cost between $170 million and $220 million to fix broken roadways and bridges on highways 1, 5 (the Coquihalla), 8 and 99. Temporary repairs to Highway 5 alone cost $45-55 million, with the job taking more than 300 workers and 200 pieces of equipment 35 days to re-open the important east-west travel route.

And that’s for just one weather event. The cost of fighting BC’s 2021 wildfires that preceded the November flooding topped $500 million, more than triple the $136 million budgeted.

Previous commodities super-cycles had one or two primary causes. The cycle that began in the mid-1960s and ran through the 1970s was all about the depreciation of the US dollar following the breakdown of the fixed exchange rate system. (President Nixon in 1971 closed the gold window, meaning foreign governments could no longer exchange gold for dollars. In 1973 the president devalued the dollar, making an ounce of gold worth $42 instead of $35. This resulted in a selloff in greenbacks for gold, and by the mid-1970s inflation was in the double digits. Later in ‘73 Nixon decoupled the dollar from gold completely, which made the price of bullion soar to $120 per ounce and ended the 100-year history of the gold standard. Read more)

As we know the cycle in the 2000s revolved around China and its steady demand for oil, gas, coal and metals.

This cycle is different because its causes boil down to a number of factors, including the demand for many raw materials outstripping supply; the heavy demand for commodities envisioned by infrastructure renewal, electrification and decarbonization; climate change; pollution abatement; and population growth. Notice we haven’t even talked about the immediate supply pressures resulting from pandemic recovery, that are resulting in multi-year highs for metals such as nickel, aluminum, copper and lithium, and record-setting natural gas prices particularly in Europe.

The question is, is there a way that the system can ramp up now, to the levels of production needed to satisfy demand, for all of the above-mentioned areas, all at the same time?

The answer is no.

Even if the investments in mining/ oil and gas that have been lacking were suddenly returned to the sector, there remains the problem of most accessible deposits having been mined out, the so-called “low-hanging fruit”. Now companies are having to go deeper underground, or farther afield, to find minerals at the scale and grades needed for extraction. Their remote locations will require huge investments in infrastructure, and those with complicated mineralogy will face higher processing costs. You still have countries wanting to protect their minerals from foreign mining companies, tax them more, or enact other forms of resource nationalism. It will still take 20 years to develop a mine in North America. The trend is for more ESG, more consultations with focus groups, meaning a lot more talk and a lot less action when it comes to regulations and permitting.

Ironically, all of these deterrents to mining are there, and growing, at precisely the same time that demand for metals is rapidly accelerating.

Conclusion

Economic growth requires the supply of raw materials for manufacturing end-products, and a litany of other industrial activities, including home construction, replacing and building new infrastructure, developing a global electrified vehicle/ rail transportation system, and constructing lower-carbon sources of electricity generation.

Unless all of these areas are continuously supplied, economic growth will drop off, hurting employment and lowering our standard of living. This becomes a major challenge when demand is coming from so many directions at the same time.

In a column about finite resources, author Gail Tverberg writes:

The economy Is facing many limits simultaneously: too many people, too much pollution, too few fish in the ocean, more difficult to extract fossil fuels and many others. The way these limits play out seems to be the way the models in the 1972 book, The Limits to Growth, suggest: They play out on a combined basis. The real problem is that diminishing returns leads to huge investment needs in many areas simultaneously. One or two of these investment needs could perhaps be handled, but not all of them, all at once.

We simply can’t afford not to continue investing in mining and oil and gas exploration. We have seen what happens when there is too much focus on renewables and not enough on the oil sector — sky-high natural gas prices, borne mostly by electricity consumers in Europe — and concerns that

without re-investing in the industry to find more deposits, the world could be short 30 million barrels a day in eight years. (about a third of global oil production in 2020 of 88Mbod)

By year-end, Goehring & Rozencwajg believes global oil demand will exceed pumping capability for the first time in history.

Here in the West, it isn’t only that we have failed to maintain mining and oil investments. We have also put roadblocks in the way of mining, such as the lengthy permitting process in North America. In Canada we’ve let interest groups hostile to corporations dictate resource policy, by allowing them to scupper oil pipelines that would help to alleviate the glut of Canadian crude that has depressed prices for decades.

We haven’t built the necessary infrastructure, either. We may have the metals but in Canada, the resources are quite often stranded, located far away from roads, railways and electricity. The Golden Triangle of northwestern BC and the Ring of Fire in Ontario are two examples. For many post-secondary school graduates, mining and oil and gas are part of the old-world economy. Unless more of an effort is made to entice them, retirements will continue to outpace new hires, leading to a severe skills shortage.

All of these factors are limits to growth.

In general there has just been a total lack of planning for what is to come; a failure to invest in, and support the natural resource sector.

In many metal markets, the West’s reluctance to mine has been China’s gain.

During the 2000s, metals were much more readily available than they are currently, and China was there, ready to sign offtake agreements and lock up valuable supplies.

We know from previous articles that China has been extremely active in acquiring ownership or part-ownership of foreign lithium mines and inking offtake agreements.

Four out of the five major copper projects in the pipeline right now either have offtakes in place with non-Western countries (South Korea and China), or the mines are partially owned by Japanese companies that have a say in where some of the mined copper is destined. (ie. Japan)

The West is so behind the curve, in bringing new metal to market, that it could take decades to catch up to Asia. Truth is, by ignoring domestic mining, we’ve been outplayed.

If there is a silver lining, it’s the fact that North Americans are finally starting to realize that to have security of supply, we need to develop our own mineral deposits.

The first step is recognizing that we have these metals, we do not need to purchase them from China, the DRC, Russia or any other foreign producer, we can mine and refine them right here.

Next is upping our exploration game — and nobody is better at it than Canadian junior resource companies — so that we can find and develop the deposits that will become the world’s next mines.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.