Extreme weather, failed climate talks, food inflation: the new normal hits home

2021.11.18

Residents of southern British Columbia only had a few weeks of peace and calm following this year’s heat and hellish forest fire season, before they were dealt another blow from Mother Nature: an unrelenting deluge that caused mudslides, forced the closure of highways, stranded motorists, and saw flooded-out residents of Merritt, parts of Abbotsford and other BC communities flee their homes under an evacuation order.

According to Global BC’s Monday night news cast, more rain fell in November in under 48 hours than average monthly totals going back as far as 1981. The District of Hope about 90 minutes east of Vancouver, and the City of Chilliwack, in the Fraser Valley, each broke records on Nov. 14, with a respective 295 mm and 219 mm of rain falling. It was truly biblical.

November is typically the wettest and stormiest month in the most westerly Canadian province. But September saw a 300% increase in precipitation, and in October on the south coast, it rained 200% to 240% more than usual.

The torrential downpour that started Sunday was the fifth “atmospheric river” to drench BC since September. An Environment Canada meteorologist said there were several factors that increased the latest storm’s intensity, including “burn scars” left from the forest fire season, and melting snow on the mountains that wasn’t thick enough to survive the rain.

It doesn’t take much of an imagination to appreciate how washed-out highways (including Highway 5, the main route connecting the Lower Mainland to the Interior) and train tracks, are impacting transportation infrastructure and supply chain logistics, including the flow of food.

The Globe and Mail reports in its Wednesday edition that floods and mudslides in British Columbia have damaged or destroyed large sections of highways and railway tracks near Vancouver, severing crucial trade corridors as bottlenecks worsen at Canada’s largest port. The Globe’s Brent Jang and Eric Atkins write that fresh disruptions this week will compound existing supply-chain problems getting imports across Canada and exports to destinations abroad. Some repairs are expected to get goods moving again within days, but other fixes to critical infrastructure will be longer-term projects.

“All rail service coming to and from the Port of Vancouver is halted because of flooding in the B.C. Interior,” the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority said in a statement. Strong winds that followed record-breaking rainfall forced GCT Global Container Terminals to temporarily close its Vanterm and Deltaport container-shipping sites for several hours on Monday. Teck Resources has rerouted some of its coal exports by rail to the Port of Prince Rupert in northwest B.C. Authorities are continuing to assess the damage before estimating a time frame for reopening rail lines severed by torrential rain, washouts and mudslides.

The Financial Post reports in its Wednesday, Nov. 17, edition that multiple pipelines delivering oil and gas to Canada’s West Coast have been knocked out. The Post’s Geoffrey Morgan writes that Enbridge spokesman Jesse Semko said on Tuesday, “Due to heavy rainfall and increasing river flows, we shut down a segment of 30-inch natural gas pipeline in the Coquihalla river valley on the morning of Nov. 16 as a precautionary measure.” The 30-inch gas pipeline is one of two that make up Enbridge’s West Coast pipeline system, which delivers natural gas from B.C.’s interior to the Vancouver region. The second pipeline in the system, a 36-inch gas pipeline, is still in operation.

The outage on Enbridge’s West Coast pipeline system is expected to have an impact on natural gas commodity prices in Western Canada. Raymond James analyst Jeremy Mccrea says the 30-inch gas pipe is a “key pipeline coming out of northeast B.C.” He notes that he would expect to see a potential impact on both Station 2 natural gas price benchmark in B.C. and at Alberta’s AECO pricing hub. He says that upstream natural gas producers need to ship their gas eastbound into Alberta for the time being.

Calling it ‘The Storm of the Century’, Bloomberg via Insurance Journal noted It’s the second time in less than five months that British Columbia — a major conduit to Asian markets and home to one of the busiest ports on the West Coast — has been paralyzed by extreme weather: wildfires and a record heat wave choked the region in the summer. This time the disruptions threaten the movement of goods ahead of the busy winter holiday season.

Flooding has halted rail services to and from the Port of Vancouver and also shut all main routes by road, the port said in a statement. It’s not yet known when Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd. and Canadian National Railway Co. will be able to re-open their lines, it said. Nearly 1,000 rail cars carrying grain are idled in the Vancouver corridor, according to estimates from Ag Transport Coalition.

With highways closed connecting British Columbia to the rest of Canada, the province’s dairy farmers are being challenged getting their supplies to market. The Goldstream Gazette reported on Tuesday that the B.C. Milk Marketing Board has directed producers in the Fraser Valley, Okanagan and Interior regions to dispose of their milk. It’s only a matter of time before this is reflected in higher milk/ dairy prices.

A summer of extreme weather

The extreme weather being witnessed across the province, first the wildfires now the flooding, has many wondering how big of a role climate change is playing.

A prolonged stretch of hot weather in southern British Columbia saw tinder-dry forests burning for months. Out-of-control wildfires, evacuation orders, and dangerous to breathe smoke that blankets communities for weeks, are now annual events in the BC Interior. According to the CBC, nearly 8,700 square kilometres of land were burned in 2021 due to wildfires, making it the third worst year on record.

On June 29, Canada’s highest-ever recorded temperature, 49.6 C, was reached in Lytton, BC. The day after, the village of 250 inhabitants was destroyed by fire — buildings razed to their foundations and the hulking wrecks of cars left smoldering.

The “heat dome” that covered much of western North America at the end of June shattered temperature records, including Portland Oregon’s 46.6C (116F) scorcher. It killed over 465 people in Canada and caused more than 600 excess deaths in Washington and Oregon. An attribution study quoted by Climate Brief said the extreme heat would have been almost impossible without climate change.

But it wasn’t the only hot weather event. A persistent heatwave across Siberia helped fuel wildfires all summer, with temperatures hitting an unthinkable 48C. Pakistan, northern India and parts of the Middle East were also seared by high temperatures surpassing 52C in places.

Britain and Europe weren’t spared either, with normally mild Northern Ireland reaching a record 31.4C in July, and seeing the first “extreme heat warning” issued in the UK. Between 400 and 800 people are said to have died from heat-related causes.

In mid-August, another heatwave blanketed parts of the Mediterranean, including Spain, Italy, Greece and Tunisia, where a record-breaking 49C caused power failures.

June, July and August were reportedly the warmest-ever northern-hemisphere summer, although globally, 2021 will likely be only the fifth to seventh hottest year on record.

The first nine months of the year saw the highest-ever concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, referring to CO2, methane and nitrous oxide.

Carbon Brief details all of the extreme weather events that happened during the summer of 2021, neatly summarized in the world map infographic below (although there should be a wildfire icon beside the orange heatwave symbol in western Canada and the US).

Along with the extreme heat, there were more than 50 hurricanes, cyclones and tropical storms during this year’s northern hemisphere summer. They included Hurricane Elsa which hit Barbados; tropical storm Grace which brought damage and flooding to Haiti just days after an earthquake, then went on to kill eight people in Mexico; Hurricane Henri which made landfall in Rhode Island, USA; and Hurricane Ida, the second worst hurricane to hit Louisiana, behind Katrina in 2005. The remnants of the Category 4 hurricane caused flash flooding in the northeastern United States, inundated subways, and drowned 11 New Yorkers in their own homes.

It was just as bad in Europe. Climate Brief states:

[Heavy] rainfall and mudslides in Turkey killed 17 people, while flash flooding in London in July caused water to gush into London Underground stations.

River flooding in Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands in mid-July made headline news across the continent after resulting in more than 180 deaths. The immediate cause of the floods was a slow-moving low-pressure weather system, but a rapid attribution study found that human-caused climate change had made the event up to nine times more likely.

Away from the Atlantic, a typhoon caused record-breaking floods in China, forcing up to a million people to relocate and killing 300, Climate Brief said. There was also deadly flooding in Nigeria and India, while in Ghana and Burkina Faso, crops were lost and crops damaged during their monsoon season.

COP26: Coal gets a pass

The sheer number and scope of extreme weather events that have played out globally over the past six months, many thought attributed to global warming, made the COP26 climate conference seem especially important. Unfortunately however, but completely unsurprising, like most of these “talking shops”, much was discussed yet little was accomplished, reminds me of the Canadian Senate.

Recently concluded in Glasgow, COP26 set out three criteria for success, none of which were achieved. This included pledges to cut carbon pledges to cut carbon dioxide emissions in half by 2030, USD$100 billion in financial aid from rich nations to poor, and ensuring that half of that money went to helping the developing world adapt to the worst effects of climate change.

Almost 200 nations accepted the deal known as the Glasgow Climate Pact, whereby each country agreed to outline their “nationally determined outcomes” and provide a progress report every five years at the UN summit.

Much was made of a contentious climate compromise aimed at keeping alive the targeted 1.5 degree-Celsius increase in global temperatures by the end of the century, aimed at limiting global warming. The planet has already warmed 1.1C compared to pre-industrial times.

For India and China to accept the deal, the text was changed to “phase down” coal, which many observers saw as a significant weakening of the original “phase out” wording. Coal is considered to be the most polluting fossil fuel, although it is also still used for power generation by hundreds of millions in the developing world.

Arguing against the provision for phasing out coal, Indian Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav reportedly said that developing countries were “entitled to the responsible use of fossil fuels” and he blamed “unsustainable lifestyles and wasteful consumption patterns” in rich countries for causing global warming. Fair play, India.

Among those highlighting the cost of failure was the Maldives’ minister for environment, Aminath Shauna. Speaking for the island nation, whose very existence is threatened due to sea rise, Shauna reportedly pointed out that to stay within the warming limit nations agreed to six years ago in Paris, the world must cut CO2 emissions essentially in half in 98 months. She said the developing world needs the rich world to step up.

“The difference between 1.5 and 2 C is a death sentence for us,” she said. “We didn’t cause the climate crisis. No matter what we do, it won’t reverse this.” Ditto, Maldives.

A CBC story made the following assessment of COP26:

In the end, the summit broke ground by singling out coal, however weakly, by setting the rules for international trading of carbon credits, and by telling big polluters to return next year with improved pledges for cutting emissions.

But domestic priorities both political and economic again kept nations from committing to the fast, big cuts that scientists say are needed to keep warming below dangerous levels that would produce extreme weather and rising seas capable of erasing some island nations.

In other words, que sera sera. The world will continue to warm, until it doesn’t, and begins to cool, just as it has always done, in geological eras lasting millions of years.

Our climate future is unknown, with the only certainties being the uncertainty surrounding weather/ climate, and the increased frequency of storms, floods, heat and drought. We would do better to accept the reality of global warming, and do what we can to prepare for it, rather than waste time in vague, toothless conferences that have done (practically) nothing, and will continue to fail us, in their goal of averting the inexorable rise in temperatures.

For example, we can fortify coastal cities against storm surges, relocate factories and populations sited too close to rising seas, and stop polluting the earth, the air, and our rivers, lakes and oceans.

Food inflation

One thing we do know, is that climate change is causing dramatic spikes in food prices.

Common sense holds that technology will be able to beat back the worst effects of climate change, as agronomics comes up with new ways to increase yields in drought-prone areas.

Unfortunately this is not proving to be the case.

The modern agricultural complex spawned by the Green Revolution may have allowed us to grow more food, but dependence on this high-cost industrial system has come at a high price, mostly for farmers.

Output did increase, but the energy input to produce a crop increased faster. This is because high-yielding seed varieties only outperform traditional varieties when adequate irrigation, pesticides and fertilizers are used.

The Union of Concerned Scientists notes that monoculture – repeatedly producing the same crop at the exclusion of others — is bad for the soil, preventing the formation of deep root systems and the buildup of organic matter, and hastening the time when the soil can no longer holds its nutrients and irrigation ends up stripping nitrates out of the soil and polluting nearby fresh water supplies.

Desertification, a process whereby land in arid or semi-dry areas becomes degraded is a global issue with more than half of Earth’s arable land affected. Currently 12 million hectares of arable land is lost to drought and desertification annually. The issue is said to affect 1.5 billion people in over 100 countries.

Desertification is made much worse by climate change.

Ranching and farming, through extensive energy inputs like diesel fuel, lights, heating, etc., generate high amounts of carbon dioxide. Farming also releases methane from cows and cow manure, and nitrous oxide from fertilizers. Both are heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

As farmlands expand to meet demand for more food, forests are destroyed to make room for crops. Trees are carbon sinks that trap CO2 and prevent warming. Their removal dampens the forests’ mitigating effects on emissions from farming, therefore temperatures continue to rise, in a feedback loop.

It’s not only the constant clearing of forest for farmland that is a fall-out from climate change. Rising temperatures have also been shown to decrease crop yields.

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

A new study showed more than a fifth of global food output growth has been lost to climate change since the 1960s, putting an estimated 34 million people on the brink of famine.

According to BNN Bloomberg, heat-related drops in crop yields affecting the supply of food could be with us for decades:

Yields of staple crops could decline by almost a third by 2050 unless emissions are drastically reduced in the next decade, according to a Chatham House report published [in September], while farmers will need to grow nearly 50 per cent more food to meet rising global demand during the same timeline.

As for what is causing food prices to tick higher, a study by Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University cites unfavorable weather patterns in the northern hemisphere, i.e., droughts and storms, and logistical challenges owing to the covid-19 pandemic. The latter includes labor shortages in Canada and the US, countries whose supply chains are highly integrated; rising freight costs; border wait; temporary closures of meat processing plants; and higher demand for groceries, as a revival of home cooking put pressure on the prices of meat, and feed grains such as soybeans and corn.

Charts below by Trading Economics show food inflation in Canada jumped from 0.9% in April to 3.9% in September, the highest annual rate since early 2016. In the United States, the price of food climbed from 2.4% to 5.3% during the same period. Beef prices in Canada rose 13%, condiments & spices went up 9.6%, dairy products were 5.1% more expensive and the price of eggs jumped 5.4%.

The country’s worst drought in decades resulted in massive production drops in key crops such as wheat. The wildfires that followed killed farm animals and withered produce.

The skyrocketing price of feed has forced many ranchers into making tough decisions. With grazing grass increasingly scarce, and feed costs quadrupling from 3 cents a pound to 12 cents in the four months to September (the price of barley has also gone through the roof states a CBC article), many have little choice but to downsize their herds, putting more upward pressure on beef prices.

US farmers have also had to rein in herds. A September report by the US Department of Agriculture said the American hog herd was 3.1% lower than the same month in 2020 — the biggest drop since 1999. According to Bloomberg,

The number of pigs born during the quarter declined by the most since 1996.

Farmers have been dialing back hog-herd expansion as slaughter plants struggled to run facilities due to a lack of labor. High animal feed supplies have also hit profits in producing pigs.

Globally, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index surged 31.3% in October year over year to its highest level since 2011. According to AgWeb Farm Journal, The vegetable oil index set a record high, soaring 16.3% from September levels, as prices for palm, rapeseed, sunflower, and canola oil all climbed.

Since October 2020, the FPI for dairy has climbed 16.2% due to rising butter and milk powder prices spurred by strong buyer demand and tightening or lower-than-expected milk supplies from major dairy exporters, Betty Berning, analyst with the Daily Dairy Report notes, adding that rising prices could have an impact on dairy demand going forward.

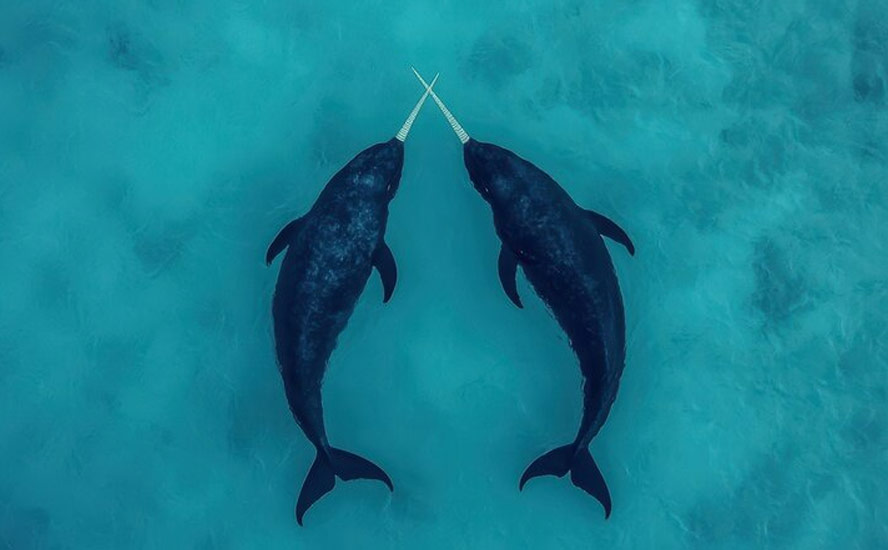

When talking about food inflation, and connecting it to climate change, we also can’t forget about how increased levels of CO2 in the oceans are affecting global fish stocks. In a previous article we discussed the perfect storm that is occurring due to overfishing and climate change. The result could mean a dramatic decline in fish stocks, with the most serious effect being malnutrition in poor countries in tropical climates that depend on fishing as a protein staple. According to the UN Environmental Programme,

Nearly 3 billion people rely on fish as a major source of protein. Overall, fisheries and aquaculture assure the livelihoods of 10–12 per cent of the world’s population. 60 per cent of the world’s populatio n lives within 100km of the coast. Marine vertebrate populations declined 49 per cent between 1970 and 2012.

Populations of fish species utilized by humans have fallen by half, with some of the most important species experiencing even greater declines.

In 2015 ocean temperatures were the warmest in 136 years. The Worldwatch Institute notes over the last 40 years the upper 75 meters of the oceans have increased by over 0.1 degrees Celsius per year. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but warmer temperatures and overfishing are pushing temperate species towards the poles where they face greater competition for food with polar animals.

Warmer ocean temperatures also cause acidification, which stunts the growth of corals and shell-based creatures like oysters. The destruction of coral reefs is a major problem resulting from climate change, since they provide critical habitat and food for so many species in the reef ecosystem.

If current rates of temperature rise continue, the ocean will become too warm for coral reefs by 2050.

World fisheries are in a state of collapse — caught between plagues of jellyfish, overfishing, nutrient pollution, bioaccumulation of toxics in marine mammals, carbon emissions turning our oceans acidic, the oceans phytoplankton declining by about 40 per cent over the past century, dead zones, garbage patches, increasing ocean temperatures and changing currents —our entire marine food chain seems to be in peril.

It isn’t only food shoppers that are feeling the pinch of rising prices. Inflation is just as much a factor at the bottom of the food supply chain, the world of farmers and ranchers, as at the top, the shelves of brand-name grocery stores where most of us peruse items for our weekly shop.

One of the most important inputs that farmers rely on for growing food is fertilizer. Higher fertilizer prices must often be passed onto the end user, the buyer of grains, fruits and vegetables, for the grower to preserve his profit margin. This is precisely what we see happening right now.

Farm Policy News reports the average price of anhydrous, a chemical used in fertilizer production, set a record $1,113 a ton last week, with seven other major fertilizers for the first week of November seeing increase ranging from 9% to 36%. The largest movers this month are nitrogen fertilizer products, with prices driven higher due to supply disruptions:

The average price of UAN28 is 36% higher than last month at $545/ton. UAN32 is 32% more expensive at $604/ton, while urea is up 26% at $820/ton. All are new records for DTN’s database.

Higher fertilizer costs are mainly due to rising natural gas prices. In the production of ammonia or urea, natural gas is processed at an upgrading plant together with nitrogen. The two main end products, ammonium nitrate and urea, are then mixed with other ingredients — mainly phosphorus and potassium — to manufacture a range of synthetic fertilizers for use on farms.

In Europe, a colder-than normal last winter depleted natural gas inventories, causing electricity prices to soar, as demand from rebounding economies surged too fast for supplies to match, BNN Bloomberg reported.

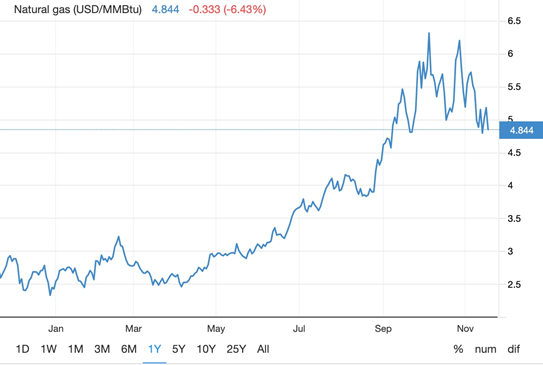

The price of NG is currently six times higher than last year and about four times higher than it was in the spring.

The European Union imports 90% of its natural gas, of which Russia is by far the largest source, at 43.4%. The latter is frequently accused of holding back supply to keep prices high, especially this year, reportedly withholding additional gas to force the opening of the newly completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline, a charge that Russian officials and Gazprom denies.

This week German regulators suspended certification proceedings for the new pipeline, adding to concerns Europe will run low on fuel this winter and causing prices for the heating and power-generation fuel to shoot even higher.

According to the Wall Street Journal, futures gained more than 15% in Europe and US prices added 3.2%.

With 40% of US electricity now generated by NG, higher gas prices will inevitably push up electricity and heating bills. US natural gas futures have already more than doubled this year.

Beyond the higher cost of crops, fertilizers and fuel, a less understood but interesting aspect of food inflation is the rising price of farmland. Progressive Farmer reports that farmland values are posting record highs and land auctioneers have never been busier. For example in northeastern Iowa, 80 acres sold at auction in late October for $13,100 per acre, a 54% jump in value compared to the same farm that sold a year ago for just $8,464/ acre. What’s behind rising farm prices?

According to Progressive Farmer, it’s due to a combination of Farm profits, low interest rates, a strong economy, inflation fears, potential tax changes and generational transfers, [that are] all pushing farmland prices higher this fall.

Conclusion

Most British Columbians have directly experienced the effects of climate change, whether it was the June “heat dome” that saw temperatures in some cities reach over 40 degrees, high winds that canceled ferries, cut power and downed trees, or most recently, the floods in southern BC that stranded motorists, cut off main transportation routes, and led to evacuation orders for hundreds of flooded-out residents.

Supply chain logistics were already hampered by covid, now we see a major weather event fouling supply lines even further. Without smooth road and rail access to key markets, delays and goods shortages are inevitable, resulting in higher inflation across many sectors of the economy, including food.

Droughts and low water levels are pushing down food production in Canada and the United States, lowering yields, and causing ranchers to cull part of their herds. Stubbornly high natural gas prices are being reflected in record-high fertilizer prices. Other farm inputs like feed and barley are going through the roof.

All of this is being passed up the food supply chain to the consumer, who is seeing double-digit inflation in some products especially meat.

Remember, monoculture and desertification were already degrading the quality of the soil, now we are seeing the impacts of extreme weather on food production including dairy farmers having to dump their milk because they are cut off from rail and road due to widespread flooding, bottlenecks at the Port of Vancouver (the country’s busiest), and multiple pipelines delivering oil and gas to Canada’s West Coast having been knocked out.

While many including the US Federal Reserve are calling the current bout of inflation “transitory” we disagree. Structural supply deficits in a number of metals, climate change, the global trend to electrify and decarbonize, and resource nationalism are all permanent fixtures of the global economy. Inflation is therefore going to continue so you had better be prepared for scarcity, insecurity of supply and much higher prices.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.