GSP Resource Corp: Open-pit copper mine potential next to Teck’s Highland Valley operation

2021.10.19

A porphyry deposit is formed when a block of molten-rock magma cools. The cooling leads to a separation of dissolved metals into distinct zones, resulting in rich deposits of copper, molybdenum, gold, tin, zinc and lead. A porphyry is defined as a large mass of mineralized igneous rock, consisting of large-grained crystals such as quartz and feldspar.

Porphyry deposits are usually low-grade but large and bulk-mineable, economics of scale come into play making them attractive targets for mineral explorers. Porphyry orebodies typically contain between 0.4 and 1% copper, with smaller amounts of other metals such as gold, molybdenum and silver.

In Canada, British Columbia enjoys the lion’s share of porphyry copper/ gold mineralization. These deposits contain the largest resources of copper, significant molybdenum and 50% of the gold in the province. Examples include big copper-gold and copper-molybdenum porphyries, such as Red Chris and Highland Valley. Large, undeveloped porphyry deposits along the North American Ring of Fire include Galore Creek in BC and the Pebble project in Alaska.

There has been a definite trend by major mining companies towards making deals with junior resource companies that own copper/gold porphyry projects in BC. Historical examples include:

Tiex/Newmont

Novagold/Teck Resources

Cariboo Rose/Gold Fields

Terrane Metals/Goldcorp

Kiska Metals (formerly Rimfire Metals)/Xstrata

Serengeti/Freeport

Strongbow/Xstrata

Copper Mountain/Mitsubishi

Copper rallying

Lately there has been a resurgence of interest in British Columbia as a copper-gold jurisdiction, especially with the copper price recently hitting an all time high of $4.79 a pound on the back of plans by several governments to electrify their transportation systems and decarbonize their sources of electricity.

Copper has been one of the biggest winners among the commodities complex since 2020.

Not only is this tawny-colored industrial metal an essential part of economic growth, it is also imperative to the global transition towards sustainable energy sources.

Because electric vehicle are copper intensive (in fact they use 4x as much copper as a regular vehicle), demand for copper has risen at an unprecedented pace with no signs of slowing down.

Meanwhile, wind and solar photovoltaic energy systems have the highest copper content of all renewable energy technologies, making the metal even more important in achieving climate goals.

According to the Copper Alliance, wind turbines require between 2.5-6.4 tonnes of copper per MW for the generator, cabling and transformers. Photovoltaic solar power systems use approximately 5.5 tonnes of copper per MW.

Cochilco, the copper commission of top producer Chile, says global copper demand will reach 24 million tonnes this year, up 2.4% compared to 2020, and 24.7 million tonnes for 2022, a 3% increase.

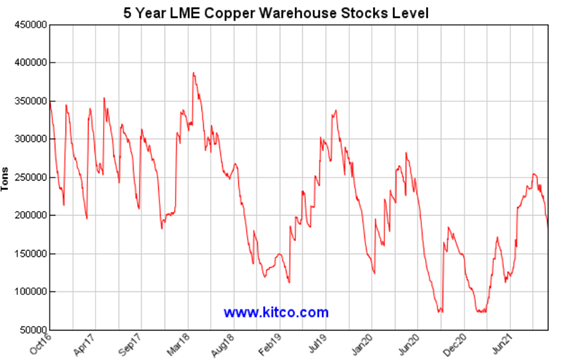

Driven by robust industrial demand, copper prices surged to an all-time high of $4.77/lb in the second quarter of this year. Compared to its trough of $1.94/lb in early 2016, this represents a 150% rally within a span of five years.

Even though copper — like many other commodities — has experienced a recent pullback, the base metal is still sitting at its highest in a decade.

Goehring & Rozencwajg, which specializes in natural resource investments, believes that the current cycle will ultimately take copper prices higher, perhaps even above $10/lb. Justifying this aggressive price target, the New York-based research firm referenced copper’s last great rally, which saw the metal grow seven-fold from its 1999 bottom of $0.61/lb to $4.57/lb in 2011.

The Goehring & Rozencwajg report also pointed out that recommendations on copper investments have focused primarily on bullish demand trends; the supply side of the equation also must be factored in.

The primary concern lies in the inevitable depletion of existing copper mines — a problem that has been brewing for over a decade.

A dearth of new copper discoveries and capital spending on mine development in recent years means that once an existing mine becomes exhausted, its output may not be replaced in time to meet the growing demand.

Moreover, since 2000, most reserve additions have come from simply lowering the cut-off grade and mining lower-quality ore as prices moved higher (i.e. Chile’s Escondida copper deposit), a practice that may not be feasible for geological reasons in the upcoming cycle, as Goehring & Rozencwajg argues.

Although there will be new projects coming online around the globe (DRC, Panama and Mongolia), these will only offset depletion at other existing mines, leading to stagnant overall mine supply growth.

Acuity Knowledge Partners, formerly part of Moody’s Corp., is predicting a widening demand-supply gap that could reach as high as 8.2 million tonnes by 2030.

Despite the current lukewarm market, investors are continuing to take positions in copper equities. Shares of COPX, the Global X Copper Miners ETF, are up 26% so far this year.

And why exploration companies holding high-quality copper assets will continue to appeal to investors.

GSP Resource Corp

One copper junior to recently catch the attention of AOTH, is GSP Resource Corp. (TSXV:GSPR, FRA:0YD). Vancouver-based and British Columbia-focused, the company’s flagship is the Alwin Mine Project located 18 km from the town of Logan Lake. The past-producing Alwin Mine is southwest of the New Afton and Ajax mines, and less than a kilometer away from the Highland Valley Mine owned and operated by Teck Resource Corp. Remember that “close-ology”, as it will be important later on in the article.

GSP Resource Corp was formed in 2018 with the goal of finding copper-gold-silver assets in southwestern BC. Management prefers the area’s three-season climate to the Golden Triangle of northwestern BC, which gets a lot of snow and therefore has a limited exploration window, roughly May to October.

Small-scale mining was conducted at the Alwin Mine in the early 1900s, with modern exploration and mining occurring in two periods, from 1967 to 1982 and from 2005 to 2008. In all about 36,000 meters of historical drilling has been completed.

The first copper occurrence discovered in the Highland Valley was the Ashcroft glory hole, an outcropping copper deposit that saw limited mining during the First World War, then lay dormant until the 1960s when it was explored on a larger scale.

From 1967 to 1970, 6,940m of surface diamond drilling in 81 holes was drilled along the main Alwin mineralized trend, and 5,860m of underground drilling in 119 holes was completed in 1,400m of mine workings.

In 1980, Dekalb Mining Corp. expanded the capacity of the mill to 700 tons per day and resumed mining of the Alwin trend. Total production was 155,000 tonnes grading 1.54% Cu. Mining was suspended in 1981 due to low copper prices. (see price chart below) At the conclusion of mining, a trackless development decline was extended to a depth of 270m and 3,935m of drilling was completed in 76 underground holes. Dekalb calculated a resource of 390,000 tonnes grading an average of 2.5% Cu, after factoring for 25% dilution. No cut-off grade was reported.

This historical resource is not National Instrument 43-101-compliant and therefore GSP is not relying on it for accuracy; more drilling needs to be done to bring the resource up to modern reporting standards.

An important aspect of the GSP story, is the fact that previous underground operators were focused on the high-grade copper mineralization — a series of deep and narrow replacement deposits. At a 1.5% cut-off grade with copper being less then a dollar a pound, and getting as low as US$0.56, the mine was never considered from a bulk tonnage, open-pit perspective. Ironic, really, considering that is precisely what the Highland Valley has become known for, with five large pits developed over the past 60 years including Teck’s Highland Valley open-cast copper-molybdenum operation.

Fast forward to today, when the economics of copper mining are completely different, with copper currently trading at $4.75 a pound compared to a ballpark average 68 cents during the 1960s and early 1980s. The much higher copper price now makes the lower-grade areas of the Alwin Mine Project more interesting if they can be developed into an open-pit mine.

The historical resource at Alwin isn’t 43-101-compliant but it was enough to inspire a geological model that GSP has been working from: a significant resource of high-grade material surrounded by a lower-grade halo, or halos, of mineralization.

From the 3D figure below, one can see there is quite a lot of un-mined material — much of it close to surface — denoted in green. This makes sense — when the resource was calculated nothing below 1% Cu was sampled or assayed.

GSP management believes there is a low-grade halo of mineralization north and south of a 500-meter-long replacement deposit. Given the presence of high-grade material around the lower-grade halo, and the fact that the head grade at the Highland Valley operation is 0.28% CuEq, the geological team has determined that a model for bulk-mining the Alwin Mine, or generating a block cave resource, is appropriate.

President and CEO Simon Dyakowski explains what was done previously and what GSP plans to do at Alwin:

“The mining was so limited, so disjointed several decades ago, they barely mined anything out,” he told me over the phone, Monday. “They gave us a lot of information but they left almost all the high-grade copper gold and silver in there, so that’s a huge bonus for us. You can see from the model it’s right under that hilltop that outcrops at surface, we’re trying to blow that whole thing out into a bulk tonnage because we’re hitting low-grade halos all the way in, underground.”

Drilling last year from the southern property boundary towards the Alwin Mine, GSP hit numerous low-grade halo structures that proved to be in excess of the Highland Valley pit’s 0.28% CuEq mining head grade. A side note: the Alwin property is so close to Highland Valley that when you stand on it you can see, hear and feel the mining trucks rolling “next door”.

The best intercept from the 2020 drill program returned 62 meters at 0.3% copper-equivalent (CuEq), “with some very high grades of silver in the guts of the high-grade zone,” Dyakowski told me.

This year the company decided to expand its step-out drilling by capturing a broader horizontal distance from the property boundary to the Alwin main zone. Three of five holes totaling 1,439m were “home runs” says Dyakowski, in terms of delineating a large open pit. Highlights included:

- 0.61% CuEq over 164.6m;

- 0.14% CuEq over 176.7m;

- 0.21% CuEq over 229.7 including 0.28% CuEq over 158.5m and 0.48% CuEq over 79.3m.

Between this year’s and last year’s drill programs it appears that GSP is successfully proving its model. Not only have the drills come up with some substantially long intercepts, up to 229m, with grades higher than Highland Valley’s cut-off, there is also the higher-grade material at the Alwin Mine.

Moreover, the company has only stepped out to the south of the mine. There is 500 meters of strike length to test and the next phase is to step out in a northerly direction. Three 300m holes are budgeted.

“We’ll capture the low-grade that was hit in hole 9 and incorporate that to what’s lurking between hole 9 and the main zone, so just the dimension of that we’re looking at 400m north-south, 500m east-west, we’re starting to be able to envision a sizeable amount of material as bulk tonnage,” says Dyakowski. (hole AM-20-09 is the northern-most drill hole shown as a pink line on the above map)

But the really exciting part of the project concerns the type of mineralization GSP could be looking at, and the proximity of the Alwin Mine Project to Teck’s Highland Valley Mine.

During 2021 drilling a new mineralized zone was discovered with hole AM21-02, shown as a dotted red circle on the above map. Previous drilling didn’t go very deep, but hole 2 of the 2021 program was completed to a depth of 367m. Near the end of the hole, the rock was found to be increasing in alteration. From 338m to 351m, the exploration team intersected what GSP describes as “an intensely mesothermal to epithermal clay style altered shear hosting dilational quartz vein fragments hosting coarse-grained pyrite and chalcopyrite.”

In plain English? This is evidence of a porphyry. Dyakowski explains:

“We punched through a lot of pyrite right in the area of a geophysical anomaly so we think that might be the top of an unknown porphyry. That’s something we’re going to save for next spring when we have a whole season of deeper drilling, but one of the main theories on Alwin is it is a skarn replacement system that’s associated with a larger porphyry.”

Recall from the top of the article, porphyry deposits are usually low-grade but large and bulk-mineable, making them attractive targets for mineral explorers.

Now, GSP doesn’t yet know whether, a/ If what was found in hole 2 means it has hit a porphyry. More drilling is required to bolster this case. And b/ If it is indeed a porphyry system, is it a porphyry unique to the Alwin Mine, or is it an extension of Teck Resources’ next-door Highland Valley copper-moly porphyry? An interesting fact to note here is Teck Resources has a copper-moly porphyry, GSP has been assaying a lot of gold and silver, the highest grades drilled yet to date in the Valley.

We do know that Teck is planning on expanding its mine and that there is a network of roads and drill pads to the west of the pit edge, as shown on the map below.

Teck doesn’t exactly tell all on its Highland Valley Copper website, but we learn from a local media source that the company is planning on extending the mine life to 2040 from its original closure date of 2027. The company is looking to expand the footprint by 800 hectares and would build out the Highmont pits and waste rock dumps. Teck has reportedly applied for permits needed to expand the more than 50-year-old operation. If approved, there would be a projected 25% increase in production, with construction starting in the first quarter of 2023.

How does the expansion affect GSP? Well again, it depends on whether the potential porphyry is its own, or an extension of Highland Valley’s. If GSP ends up discovering a new porphyry next to Highland Valley’s deposit, it may open up the possibility of a partnership with Teck, which could use ore from the Alwin Mine as mill feed for its own operation, maybe even expanding it beyond 2040.

Dyakowski says he’s confident “we’ve got more than enough space to develop our own open-pit deposit and potentially look at a block cave just on our ground, but it does beg the question what is just over the line to the south and to the east, given that they are planning to mine there.”

Forgetting about Teck for a moment, GSP has other options besides partnering with the Canadian mining major. Only 45 minutes drive away on a paved highway is Nicola Mining’s fully permitted mill which is open to contract milling. Another potential partner is New Gold, which operates the New Afton Mine to the northeast. Gold Mountain Mining, focused on re-opening the Elk Mine about 57 km from Merritt, has been trucking their ore to New Afton for processing, suggesting that GSP could do the same with its ore from Alwin.

“Alwin couldn’t be in a better location from a development perspective,” says Dyakowski, “it’s very much a brownfields development in all directions.”

Conclusion

The bottom line is that GSP has options, arguably more than the average junior.

The fact that Alwin is a brownfield project opens it up to a potential partnership with a major mining company; majors typically look more favorably at brownfields vs greenfields because they are less costly and risky, and what better place to find a mine than in the headframe of an existing mine?

Teck is the obvious choice, given Highland Valley’s close proximity to Alwin, and the fact that Teck wants to expand the mine to the west (there is of course the “dream outcome” of Teck taking over GSP) but it is not the only one.

The fact that GSP drilled the highest-grade gold and silver ever reported in the Highland Valley this year — hitting 3.5% Cu, 2.4 g/t Au and 39 g/t Ag — puts New Gold in play because New Afton is a copper-gold-silver operation.

“Basically we’ve got elements of what the two major operations are recovering, at our property,” says Dyakowski.

Even the worst case scenario is actually good. This being if GSP fails to attract a partner and ends up developing the deposit on its own, without any help, in effect becoming a contract miner. What junior doesn’t dream of having a steady flow of cash and dividends? The cash builds a company – buy more properties and develop them or hive them off for a handsome profit? Investors would love dividends, such a rarity in this sector.

Of course it’s early days, so we can’t get ahead of ourselves. Suffice to say that having multiple options is clearly an advantage for GSP, and with the share float a very sparse 20 million o/s, there is a ton of upside to a company whose focus is copper — a metal so essential to our economic future, that electrification and decarbonization can’t happen without it.

GSP Resource Corp.

TSXV:GSPR, FRA:0YD

Cdn$0.20, 2021.10.18

Shares Outstanding 20.2m

Market cap Cdn$4.0m

GSPR website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard does not own shares of GSP Resource Corp. (TSXV:GSPR). GSPR is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.